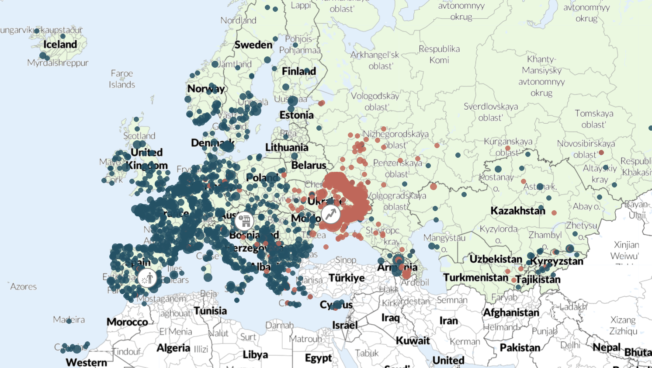

Regional Overview

Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia

September 2024

Posted: 3 October 2024

Armenia-Azerbaijan: Yerevan claims a coup plot around the anniversary of the fall of Artsakh

On 18 September, Armenia’s Investigative Committee reported having detained several men who allegedly recruited Armenian nationals and ethnic Armenians displaced from the former Artsakh1The disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh is internationally recognized as part of Azerbaijan. ACLED refers to the former de facto state and its defunct institutions in the hitherto ethnic Armenian majority areas of Nagorno-Karabakh as Artsakh — the name by which the de facto territory used to refer to itself. For more on methodology and coding decisions around de facto states, see this methodology primer. to undergo training in Russia in order to overthrow the current Armenian government upon return.2Investigative Committee of the Republic of Armenia, ‘Case of Preparation to Usurp Power Disclosed; Criminal Prosecution Initiated against 7 people, 3 of them Detained,’ 18 September 2024 There has been no information as to the number of people involved beyond seven recruiters, of whom four are at large. Armenia’s relations with Russia have been strained due to the Moscow-led Collective Security Treaty Organisation military alliance’s refusal to offer Armenia assistance during Azerbaijan’s shelling of its territory in September 2022 and Russian peacekeepers not intervening in Azerbaijan’s takeover of Artsakh in September 2023.3Thomas de Waal, ‘Armenia Navigates a Path Away From Russia,’ Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 11 July 2024

The first anniversary of the exodus of Artsakh Armenians following Azerbaijan’s September 2023 offensive passed calmly. However, the Azerbaijani Defense Ministry alleged five instances of Armenian gunfire toward its positions, including four in the direction of its Nakhchivan exclave. This area was a relative backwater in terms of armed violence compared with the volatile main land border between the two countries until the uptick in clashes in the months preceding September 2023. In addition, Azerbaijan rejected Armenia’s suggestion that the draft peace agreement between the two countries be amended to exclude a number of contentious points, one of which likely concerns references to Artskah in Armenia’s founding documents. Armenia’s Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan floated the idea that the country’s Constitutional Court could trigger amendments to the founding document during the approval of the agreed peace treaty.4Arshaluys Barseghyan, ‘Azerbaijan refuses to sign peace treaty based on already agreed points,’ Open Caucasus Media, 11 September 2024; The Prime Minister of Armenia, ‘Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan’s speech at the 79th session of the UN General Assembly,’ 26 September 2024

See also ACLED visual report ‘Destruction of Armenian heritage in Nagorno-Karabakh’

Kosovo: Tensions rise in ethnic Serb-majority north

Tensions are rising in northern Kosovo, where central ethnic Albanian authorities continue to dismantle parallel Serbian local governance structures after banning the use of the Serbian dinar in early 2024.5Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty, ‘Kosovo Going Ahead With Dinar Ban, But With “Easy Transition,”’ 31 January 2024; Associated Press, ‘EU reprimands Kosovo’s move to close down Serb bank branches over the use of the dinar currency,’ 21 May 2024 These parallel structures catered to the local ethnic Serb majority, who largely reject Kosovo’s 2008 secession from Serbia. After shutting down all Serbian post offices in the area and taking over administrative buildings hitherto run by these parallel structures in August, Kosovan police took over three more such buildings in Zvecan, Leposaviq, and North Mitrovica in September. Employees of the parallel structures took to the streets demanding reinstatement, while ethnic Serb demonstrators briefly blocked three border crossings with Serbia and heckled visiting Kosovan authorities in North Mitrovica.

Unrest is translating into increasing security incidents in Kosovo. On 4 September, unidentified perpetrators hurled hand grenades at a recently refurbished building to be used by the government in Leposaviq, as well as the front yard of an ethnic Serb’s house in Zubin Potok. In addition, unidentified perpetrators planted a mortar shell and set a recently renovated building that was to be used by the central government in North Mitrovica on fire on 17 September and vandalized a Serbian Orthodox Church in Zubin Potok on 23 September. Both Kosovo forces and NATO-led peacekeepers ramped up patrolling and exercises in the area, while Kosovo police conducted weapons seizures in both ethnic Albanian- and ethnic Serb-majority areas. EU-brokered talks between Serbia and Kosovo reached a stalemate6Matthew Karnitschnig and Una Hajdari, ‘War of words between Serbia and Kosovo intensifies as EU talks stall,’ Politico, 19 September 2024 after unrest broke out over central authorities’ attempt to inaugurate ethnic Albanian mayors in ethnic Serb majority municipalities in June 2023 and ethnic Serb paramilitaries’ raid into Kosovo in September 2023.

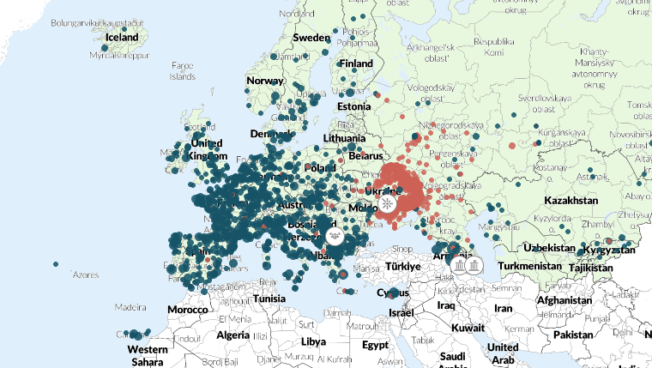

Russia: Ammunition storage facilities come under drone attack

On 18 September, Ukrainian drones hit a Russian arsenal in Toropets, Tver region, less than 400 kilometers west of Moscow. The cascading detonations were comparable to small earthquakes, prompting the evacuation of about 3,000 civilians, of whom 17 were injured. The site may have stored some 30,000 tonnes of munitions, mostly artillery shells7dAngelica Evans et al., ‘Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment,’ Institute for the Study of War, 22 September 2024 but also rare ballistic missiles, which Ukrainian forces have struggled to intercept. Later in September, Ukrainian drones conducted another strike on a weapon-holding facility near Toropets and targeted smaller ammunition depots in Russia’s southern Krasnodar and Volgograd regions. In the past three months, ACLED records increased Ukrainian targeting of ammunition depots and especially military airfields, amid Russia’s relentless aerial bombardment of Ukraine’s frontline and border regions and hinterlands. Such strikes come in addition to attacks on Russia’s oil storage facilities and refineries.

Meanwhile, overnight on 10 September, Russian forces went on the offensive in an attempt to claw back border areas of the Kursk region, which Ukrainian forces seized during their surprise incursion in August. While regaining the western part of the Ukrainian bridgehead south of Korenevo, Russian forces were unable to draw closer to the town of Sudzha further southeast, possibly due to the follow-up Ukrainian incursion into the Kursk region southwest of Korenevo, which targeted the flank of Russia’s counter-attacking force.

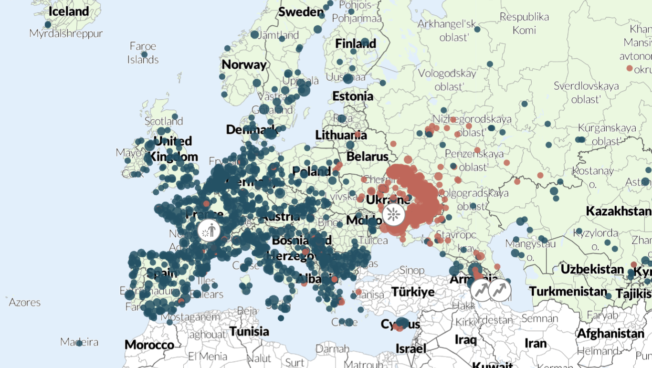

Ukraine: Russia goes after Vuhledar

Having approached the Ukrainian logistics hub in Pokrovsk in the central part of the Donetsk region in August, Russian forces appeared to have prioritized seizing Kurakhove and the semi-encircled town of Vuhledar further south, from which Ukrainian forces retreated by 30 September. Vuhledar was the main target of Russia’s unsuccessful 2023 winter offensive, though its importance for a Russian rail link toward occupied parts of southern Ukraine and Crimea has waned since the completion of an alternative railroad along the Azov Sea.8Cristian Segura, ‘Russia finalizes train line to connect to the occupied Ukrainian territories in the Sea of Azov and Crimea,’ El Pais, 21 June 2024 Urban fighting was ongoing in Chasiv Yar, Toretsk, and Selydove throughout the month. In addition, Russian forces intensified armor rather than infantry-led assaults in the area of Kupiansk in the Kharkiv region, seeking to push Ukrainian defenders beyond the Oskil River.9Riley Bailey et al., ‘Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, September 27, 2024,’ Institute for the Study of War, 27 September 2024 Ukrainian military officials also claim Russia is amassing troops in the Zaporizhia region.10Kyiv Independent, ‘Russia preparing for assault operations in Zaporizhzhia Oblast, Ukrainian military says,’ 28 September 2024

Meanwhile, Russian airstrikes overtook shelling as the primary cause of civilian casualties in Ukraine for the first time since the beginning of the invasion. This was mostly due to the scaled use of heavy and highly destructive aerial glide bombs11Dan Peleschuk, ‘Key facts about Russia’s highly destructive ‘glide bombs,’ Reuters, 25 September 2024 against the northern regions of Sumy and Kharkiv since the Ukrainian incursion into Russia’s Kursk region and the intensifying drone targeting of the Ukrainian-held part of the Kherson region in the south. This has driven up both the number of events and associated fatalities for the past three months.

For more information, see the ACLED Ukraine Conflict Monitor.

See More

See the Codebook and the User Guide for an overview of ACLED’s core methodology. For additional documentation, check the Knowledge Base. Region-specific methodology briefs can be accessed below.

Links:

For additional resources and in-depth updates on the conflict in Ukraine, check our dedicated Ukraine Confict Monitor.