Watch the recorded webinar examining how the fallout of the Sinaloa Cartel dispute has set off a broader realignment of criminal groups in Mexico and opened up opportunities for new conflicts in contested territories.

The arrest of Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada in the United States on 25 July 2024 marked a breaking point for the Sinaloa Cartel. Amid simmering tensions as a result of previous disruptions in its top leadership, the arrest of the former top leader led to an all-out war between two of the cartel’s factions, Los Chapitos and El Mayo, to the extent that many have begun to question the cartel’s continued existence. The rift has led to a spike in violence in the group’s stronghold in Sinaloa, but it has also started to spread in territories controlled and disputed by the Sinaloa Cartel as other criminal groups seek to leverage the fracture for territorial expansion. The outbreak of clashes and attacks in September 2024 following El Mayo’s arrest1Animal Político, “Sinaloa records 19 homicides and 80 other crimes amid clashes between organized crime groups,” 14 September 2024 (Spanish) contributed to 2024 recording some of the highest levels of violence involving non-state armed groups in Mexico over the last six years, and has since contributed to persistently high levels of violence across the country.

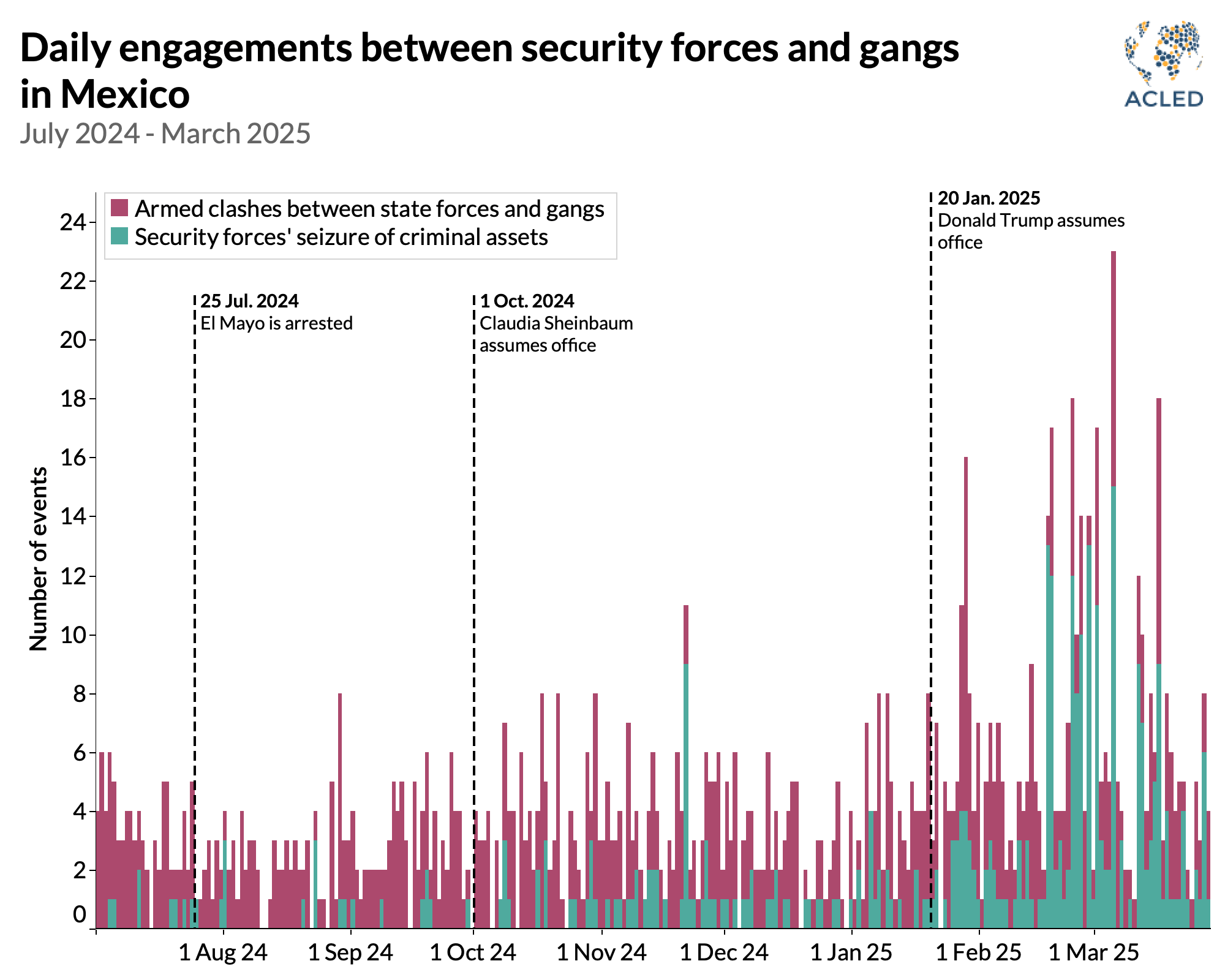

Confronted with preexisting and emerging conflicts, President Claudia Sheinbaum has started to implement her new security plan, which she unveiled upon taking office on 1 October 2024. The state response under the Sheinbaum administration has involved heightened deployments, intelligence-led operations, and high-profile arrests. These actions are partly influenced by renewed pressure from the Trump administration to reduce drug trafficking and migration, as United States politicians are contemplating unilateral military strikes against criminal organizations in Mexico. Although still in its early stages, there are few signs that these efforts have meaningfully weakened criminal groups. Instead, measures the government is undertaking suggest it may be reenacting the “kingpin” strategy used by President Felipe Calderón to topple criminal groups’ top leadership, which risks fueling the emergence of opportunistic criminal actors.

The fallout of the Sinaloa Cartel dispute has set off a broader realignment of criminal groups and openings for new conflicts in contested territories. To understand the significance of the Sinaloa Cartel’s rift and its impact on gang violence dynamics, it is necessary to understand how it came to garner such influence and how its internal structure has enabled its expansion across the country.

The Sinaloa Cartel, its operations, and internal divisions

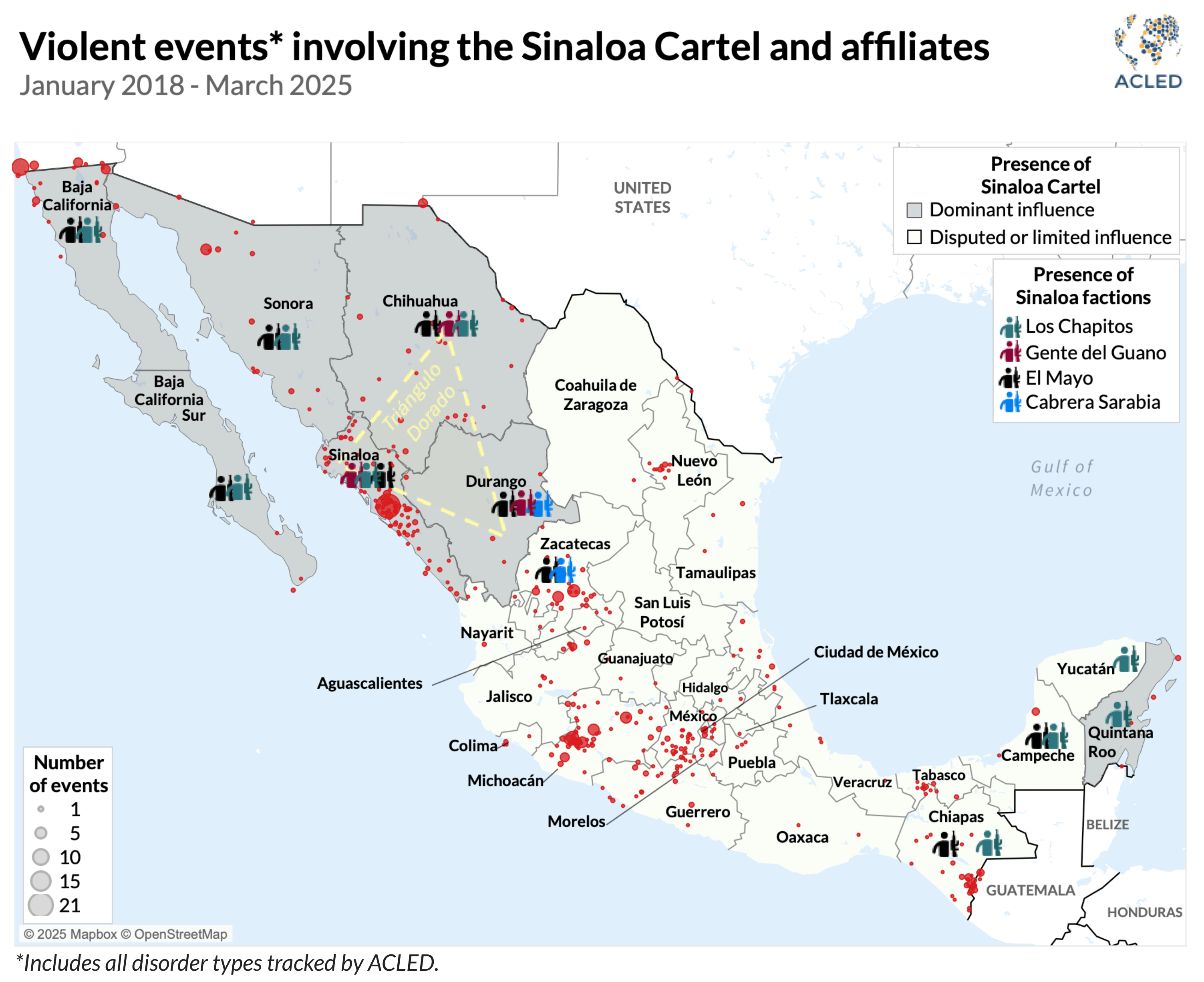

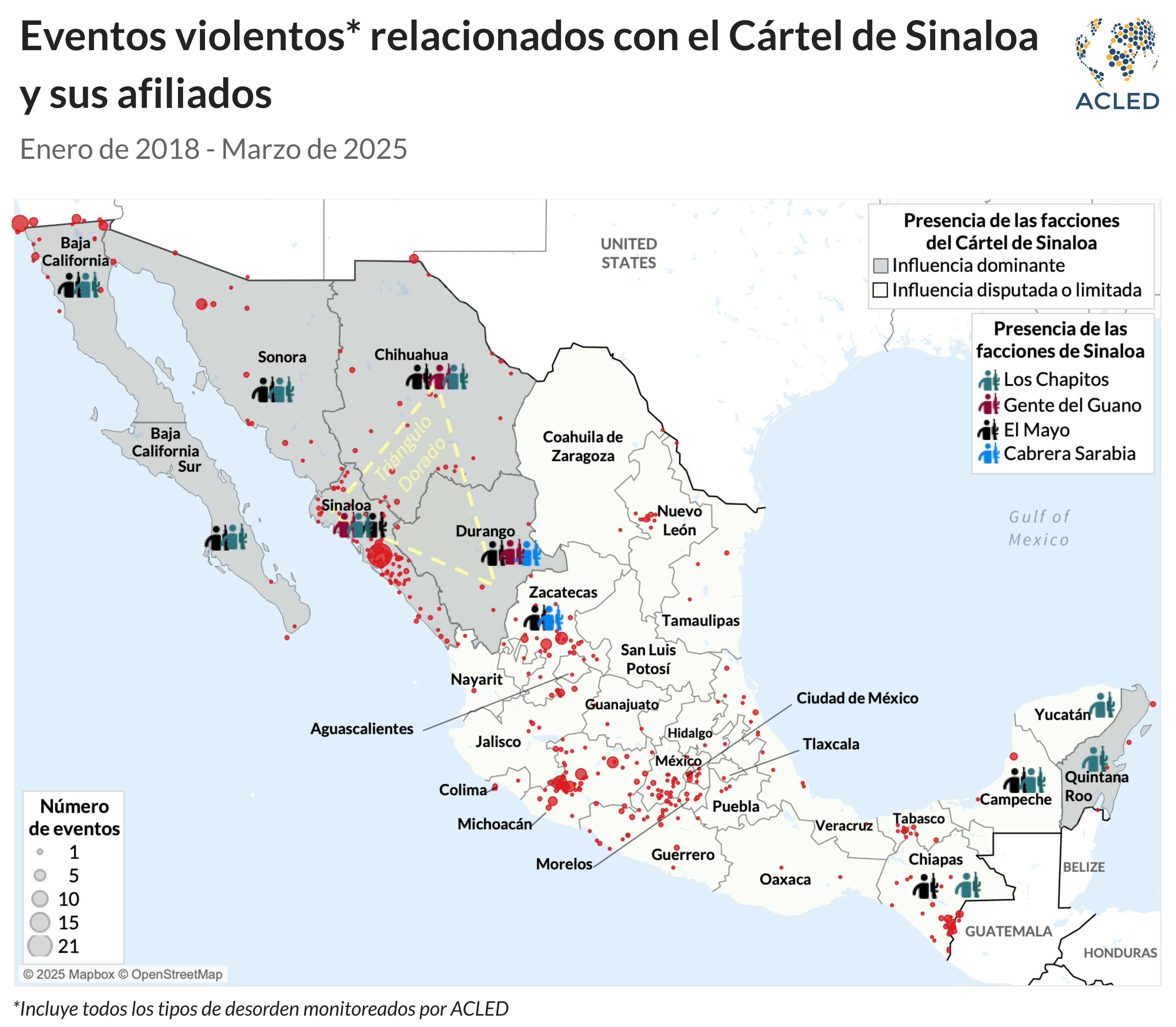

The Sinaloa Cartel, one of Mexico’s largest criminal groups, has a federal structure that allows its factions and allies to maintain full operation autonomy and horizontal relations without a rigid hierarchy.2InSight Crime, “Sinaloa Cartel,” 15 March 2024 In the early 1990s, the Sinaloa Cartel consolidated its operations under the leadership of former members of the fractured Guadalajara Cartel: Joaquín Guzmán, known as “El Chapo,” Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada, and Juan José “El Azul” Esparragoza.3Samantha Pérez Dávila and Laura H. Atuesta Becerra, “Fragmentation and cooperation: the evolution of organized crime in Mexico,” Programa de Política de Drogas, 2016, p. 19 (Spanish) The criminal organization helmed by these three leaders established its strongholds in Sinaloa, Durango, and Chihuahua states, particularly around the mountainous area known as “the Golden Triangle,” where the cartel controlled poppy and marijuana crops.4BBC, “What is the ‘Golden Triangle’, the area where the military operation tracking El Chapo Guzmán is taking place?” 17 October 2015 (Spanish) With time, the cartel has diversified its criminal activities, involving itself in the production of synthetic drugs, extortion of agricultural industries, and other legal and illegal businesses.5La Vanguardia MX, “Organized crime suffocates agricultural producers in Sinaloa,” 16 February 2025 (Spanish); Andrés Martínez, “The Sinaloa Cartel’s tentacles reach 35 legal businesses, according to Edgardo Buscaglia,” Infobae, 12 July 2024 (Spanish) While these states have been crucial for operations, the cartel has also formed alliances with local criminal groups to expand its influence in strategic areas connecting to the northern border in Sonora and Baja California states and the south in Chiapas and Quintana Roo states.

The leadership of the cartel has been shaken on several occasions, notably after the arrests of two of the cartel’s historical leaders and the suspected death of El Azul in 2014, leading to readjustments between the different factions.6Anyeli Tapia Sandoval, “What happened to Juan José Esparragoza, known as ‘El Azul’, and why is the US still searching for him even though he’s said to be dead?” Infobae, 29 October 2024 (Spanish) In 2016, Mexican authorities arrested El Chapo, who was later extradited to the US in 2017.7InSight Crime, “Joaquín Guzmán Loera, alias ‘El Chapo,’” 29 March 2019 More recently, on 25 July 2024, El Mayo was arrested in the US along with Joaquín Guzmán López, one of El Chapo’s sons.8France 24, “The fall of ‘El Mayo’ Zambada: How was the powerful drug lord captured?” 31 July 2025 (Spanish) Following the arrests of these high-profile figures, the leadership of the cartel’s factions has been transferred to their family members.

Currently, the cartel comprises two main factions, both of which are connected to the cartel’s founding members. The faction led by El Chapo’s sons, known as Los Chapitos, operates primarily in Sinaloa and has a strong presence in the municipality of Culiacán and on the Pacific coast of the state, as well as in Sonora and Baja California (see map below), where they have disputed territorial control with rival groups.

Information on the presence of the Sinaloa Cartel and affiliates and the cartel’s factions per state is sourced from the NarcoData project (2020), Mexico Violence Resource Project (2021), and X @laloguerrero, 27 July 2024.

For the purpose of this report, Sinaloa Cartel-affiliated groups are determined based on the network analysis of Nathan P. Jones, et al., “A Social Network Analysis of Mexico’s Dark Network Alliance Structure,” Journal of Strategic Security, 2022, p.7, complemented with more recent information on gang affiliations.

The other main faction was led by El Mayo. After his arrest, it came under the control of one of his sons, who is known as “El Mayito Flaco.”9Gustavo Castillo García, “El Mayito Flaco, the successor at the head of the cartel: DEA,” La Jornada, 27 July 2024 (Spanish) The El Mayo faction dominates operations in Durango and rural areas of Sinaloa and has a strong presence in Baja California, Sonora, and Zacatecas.

Other groups have formed part of the cartel federation and, at times, have competed with the Los Chapitos and El Mayo factions. Notably, the factions and cells that have maintained relevant ties with the founding leaders of the cartel are the Gente del Guano criminal group, led by El Chapo’s brother Aureliano Guzmán Loera, known as “El Guano,” and one led by the Cabrera Sarabia family, traditional partners of El Mayo.10Daniel Wachauf, “‘El Guano,’ brother of ‘El Chapo’ Guzmán, escapes during the arrest of his security chief, ‘R8’,” El Universal, 9 July 2024 (Spanish); Miguel Flores, “From being friends with ‘Los Chapitos’ to stalking them in the US: this is the criminal story of ‘El Mini Lic,’” Infobae, 14 December 2024 (Spanish); Ernesto Jiménez, “This is how the alliance between the Zambadas and the Cabrera Sarabias began, the group that is fighting the war against Los Chapitos,” Infobae, 4 January 2025 (Spanish)

By virtue of its federal structure and system of alliances, the Sinaloa Cartel has been able to consolidate its presence in several states, especially along the northern border. However, its presence along this strategic trafficking corridor has constantly generated rivalries as other criminal organizations have aimed to leverage the cartel’s internal tensions to challenge its hegemony in its stronghold. Although the cartel had managed to maintain relative unity, the arrest of El Mayo, which his supporters blame on El Chapo’s sons, marked a turning point. They claim the Los Chapitos leader, Joaquín Guzmán López, betrayed El Mayo to US authorities in the hopes of gaining leverage for himself and his brother, Ovidio Guzmán López. Both are facing charges in the US.11Elías Camhaji, “The fall of ‘El Mayo’ Zambada: a timeline of the scandal that rocked Mexico,” El País, 21 February 2025 (Spanish); Luis Chaparro, “From prison, ‘El Chapo’ Guzmán planned the kidnapping of ‘El Mayo’ in coordination with the United States,” Proceso, 4 November 2024 The dispute sparked an open war that threatens the federation’s stability.

Sinaloa’s factional turf war spreads across the cartel’s stronghold

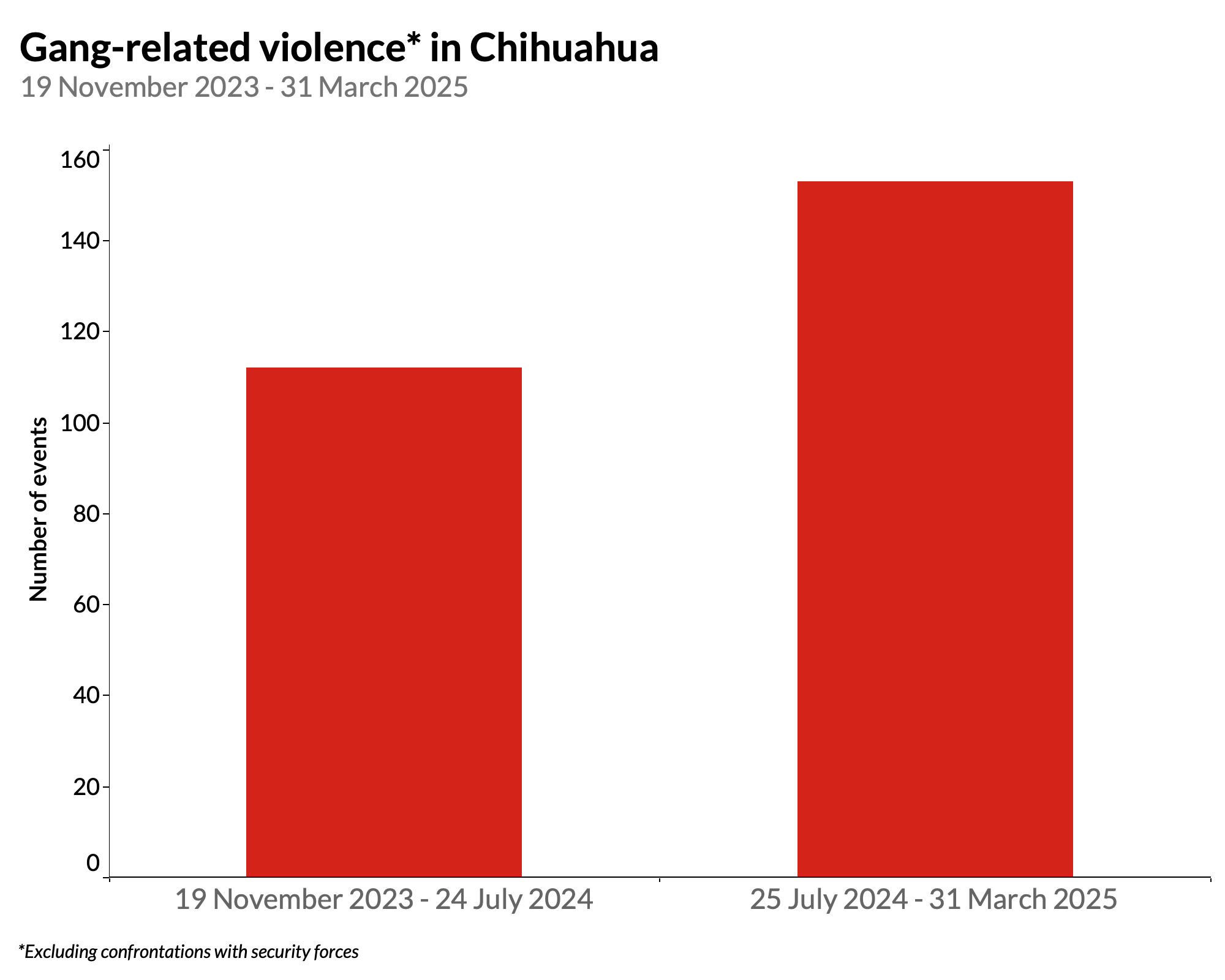

Los Chapitos’ alleged treason triggered an open conflict with the El Mayo faction in Sinaloa, the hotbed of the dispute. While the cartel had gone through internal disputes in the past, El Mayo and other cartel leaders were known for their role as mediators who helped to reduce the risk of direct conflict between the factions.12Valentín Pereda and David Décary-Hetu, “Illegal Market Governance and Organized Crime Groups’ Resilience: A Study of The Sinaloa Cartel,” The British Journal of Criminology, March 2024, p. 333 Following a period of adjustment after El Mayo’s July 2024 arrest, during which limited violent incidents involving rival cartel members occurred, the factions engaged in a wave of clashes and attacks that started in earnest on 9 September. Between July 2024 and March 2025, gang targeting of civilians and gang-on-gang clashes nearly quadrupled compared to the period from 19 November 2023 to 24 July 2024, the previous eight months, reaching a peak in October and November. The violence reached levels never seen in this state since ACLED began coverage of Mexico in 2018.

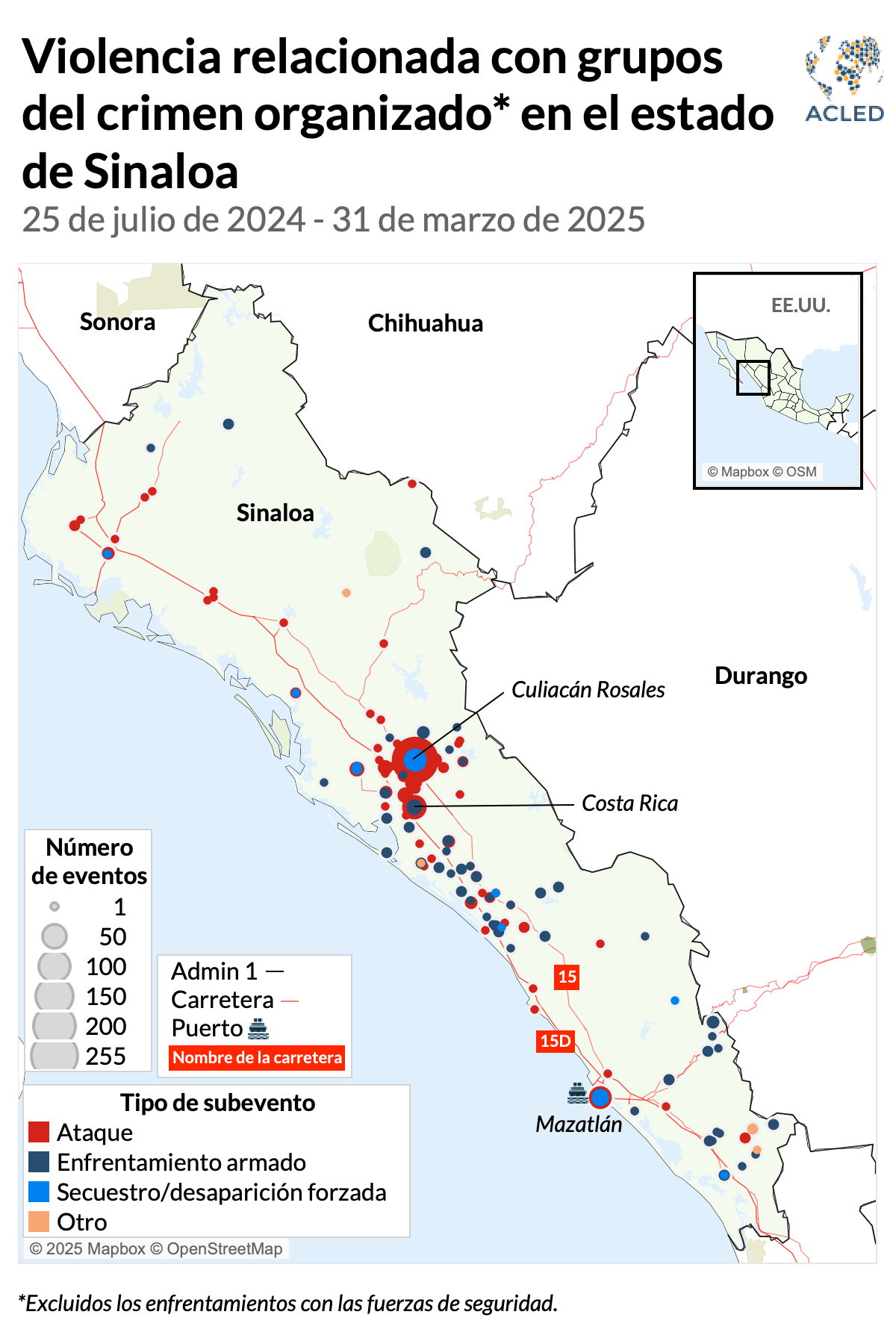

The escalation of the conflict seems to be driven by the El Mayo faction’s interest in increasing its control in towns and cities along the coast, where the Los Chapitos faction has maintained more influence, in order to broaden the scope of its operations, which have traditionally been concentrated in areas bordering the state of Durango.13Anabel Hernández, “All-out war: Los Chapitos bomb Golden Triangle,” Deutsche Welle, 1 November 2024 (Spanish) Violent actions in Sinaloa had concentrated mainly in the state’s capital city, Culiacán, which, even before the outbreak of the conflict, was the scene of disputes by these factions and smaller groups that fought for the control of extortion operations and the local drug market.14InSight Crime, “The Chapitos’ Monopoly on Drug Sales in Culiacán, Sinaloa,” 6 December 2022 However, violence has since spread into rural areas of the Culiacán municipality and other southern municipalities as the factions seek to redraw the borderlines of their respective zones of influence. Notably, after El Mayo’s arrest, violence has intensified in the south along the Pacific coast following the state’s main roads, including the federal highways 15 and 15D that connect Culiacán to the second main city, Mazatlán, which has an important touristic and commercial port controlled by the cartel (see map below).15US Department of Justice Drug Enforcement Administration, “National Drug Threat Assessment 2024,” May 2024, p. 8

Sinaloa has become the stage of alarming levels of violence targeting civilians. ACLED records a high number of killings since September, which is at odds with the Sinaloa Cartel’s reputation for using less overt violence against civilians.16Valentín Pereda and David Décary-Hetu, “Illegal Market Governance and Organized Crime Groups’ Resilience: A Study of The Sinaloa Cartel,” The British Journal of Criminology, March 2024, p. 338 Civilians have been targeted in retaliatory attacks for their suspected links with any of the rival factions. Kidnappings and forced disappearances have also been on the rise, as these groups seek to instill fear and extort ransoms from relatives.17Amílcar Salazar Méndez, “War between Chapitos and Mayiza unleashes wave of disappearances and extortions,” Milenio, 29 December 2024 (Spanish)

Public displays of violence and targeted attacks on prominent figures believed to be connected to or critical of the cartel’s leaders, including social media influencers, have served to advertise the strength of the different factions and intimidate their followers.18Online interview with Daniel Weisz Argomedo, an expert on organized crime and security dynamics, ACLED, April 2025; El Imparcial, “‘Chapitos’ vs. ‘Mayitos’: These are the six influencers killed in the Sinaloa Cartel’s internal war,” 29 March 2025 (Spanish) The factions have further targeted politicians and political authorities to establish control over localities and diminish their rivals’ political influence. Since El Mayo’s arrest on 25 July 2024, ACLED records at least 10 targeted attacks against political figures in Sinaloa, some of whom are believed to have ties with one of the cartel’s factions.19Sonora Presente, “The Sinaloa cattle rancher leader who was murdered for being a financial operator of El Mayo Zambada,” 3 October 2024 (Spanish) The number of such attacks surpasses the levels recorded in the previous eight months in a state where the relative hegemony of the Sinaloa Cartel contributed to fewer attacks, even during electoral periods.

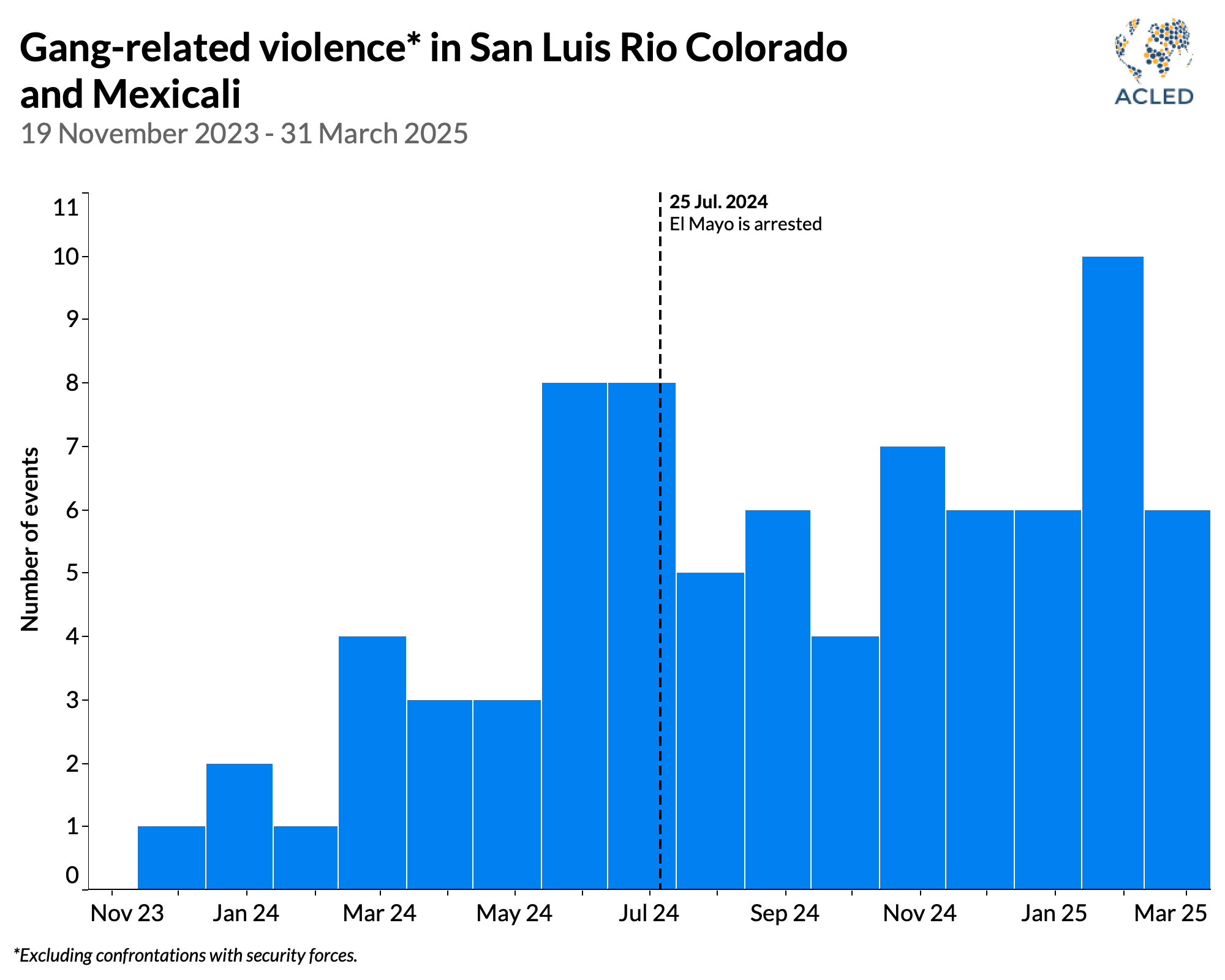

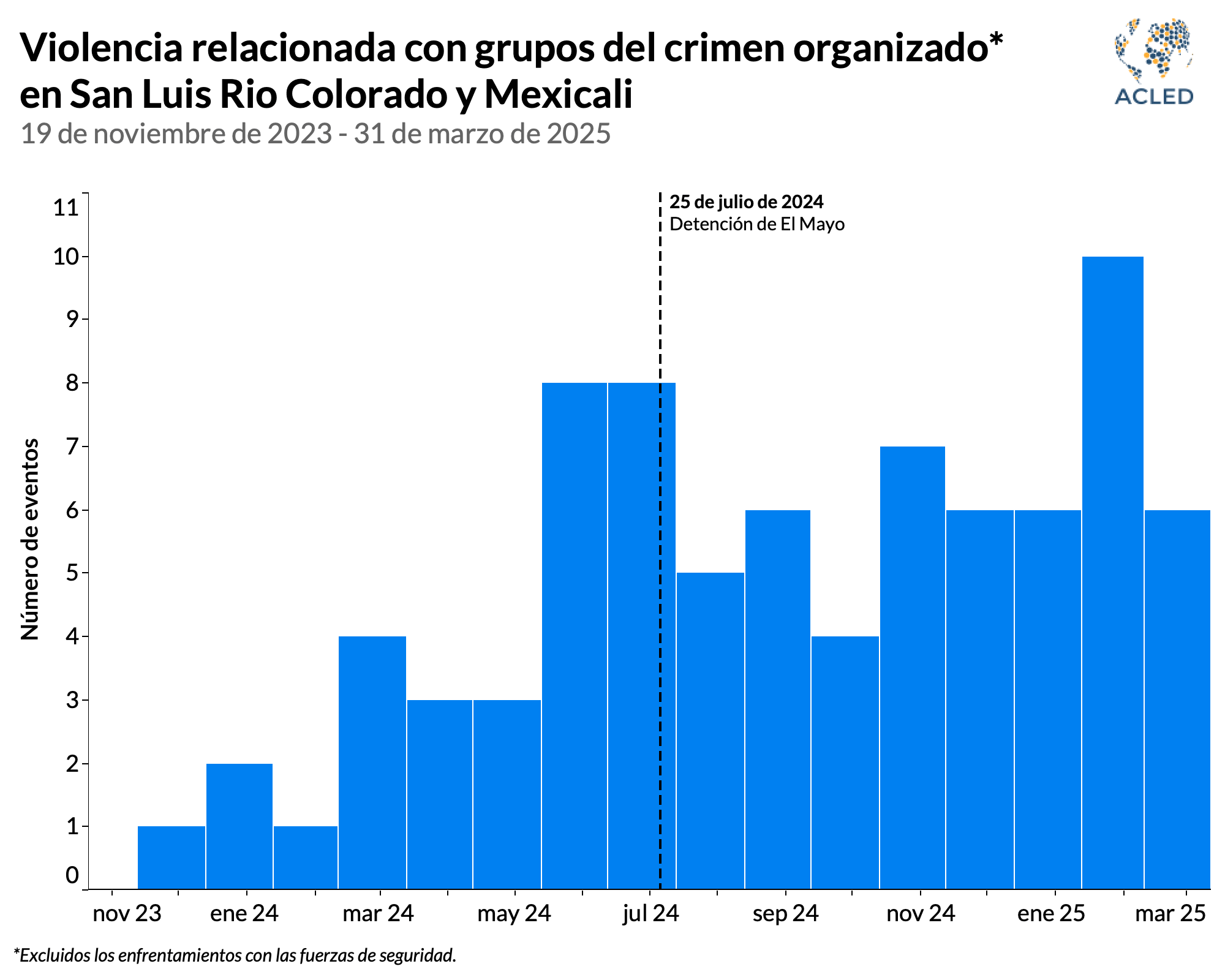

Outside of Sinaloa, the cartel’s turf war has also affected Sonora and Baja California, where ongoing disputes between allies of each faction involved in cross-border drug, weapons, and human trafficking escalated.20Anel Tello, “Los Rusos and Los Chapitos: the facets of their dispute over San Luis Río Colorado,” Milenio, 21 March 2024 (Spanish); Rubi Martínez, “Does it belong to Los Chapitos or ‘El Mayo’ Zambada? Drug tunnel discovered in Sonora near the US border,” Infobae, 3 May 2024 (Spanish) After the outbreak of the infighting following El Mayo’s arrest, violence in the neighboring municipalities of San Luis Rio Colorado in Sonora and Mexicali in Baja California has intensified amid disputes between Los Rusos (allies of El Mayo), Los Chapitos, and Los Salazar (a former partner of Los Chapitos) (see graph below).21Ernesto Jiménez, “This is the origin of Los Rusos, one of Mayito Flaco’s main allies in the war against Los Chapitos,” Infobae, 11 September 2024 (Spanish)

There are also growing signs that the dispute between rival factions could be spilling into other areas, such as the state of Durango, where violence levels have been relatively low in recent years.22Online interviews with Daniel Weisz Argomedo and Armando Rodríguez Luna, experts on organized crime and security dynamics, ACLED, April 2025 In the eight months since El Mayo’s arrest, attacks and explosions perpetrated by non-state armed groups have increased, spurred by the greater use of drones. ACLED records at least 15 actions by armed groups that included the use of a drone charged with explosives,23Andrés Martínez, “Explosives dropped from drones in the community of Eldorado, Sinaloa, residents report,” Infobae, 8 November 2024 more than double the number of events recorded in the eight preceding months.

Rival criminal organizations seek to exploit the Sinaloa Cartel rift

The consequences of the Sinaloa Cartel’s rift extend beyond internal dynamics as other criminal groups leverage the cartel’s strained operational capacities to make territorial advances or forge new alliances.24Ernesto Jiménez, “The CJNG could approve the division of the Sinaloa Charter to attack its territories, affirmed José Reveles,” Infobae, 6 September 2024 (Spanish)

One of the groups seemingly seeking advantage from the Sinaloa Cartel’s internal rift is its main rival, the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG). Since the Sinaloa Cartel’s fracture, ACLED data point to an intensification of the conflict between the two cartels in areas of illicit activities. A notable example is Tijuana, Baja California, where clashes between non-state armed groups and their targeting of civilians increased by 16% between 25 July 2024 and 31 March 2025, compared to the eight months prior. The surge has particularly affected the city’s northern districts along the US border, where the Sinaloa Cartel and other criminal groups — including the Tijuana Cartel and CJNG, which has expanded in the state since at least 201425Michael Lettieri, “Mapping Criminal Organizations in Mexico,” Mexico Violence Resource Project, 2021 — compete for the control of cross-border trafficking activities in this critical corridor. Similar dynamics are also at play in Manzanillo, Colima, where the dispute between the CJNG and the Sinaloa Cartel over control of the port — a key hub for drug trafficking — has intensified. Meanwhile, in the Huajicori municipality in Nayarit, the El Mayo faction of the Sinaloa Cartel and the CJNG have both sought to secure the route connecting the state of Sinaloa with Zacatecas, a crucial link between the Pacific coast and the northern trafficking corridor. The escalation in violence in localized and highly strategic areas suggests a deliberate effort to concentrate their warring power and assert dominance in vital trafficking points.

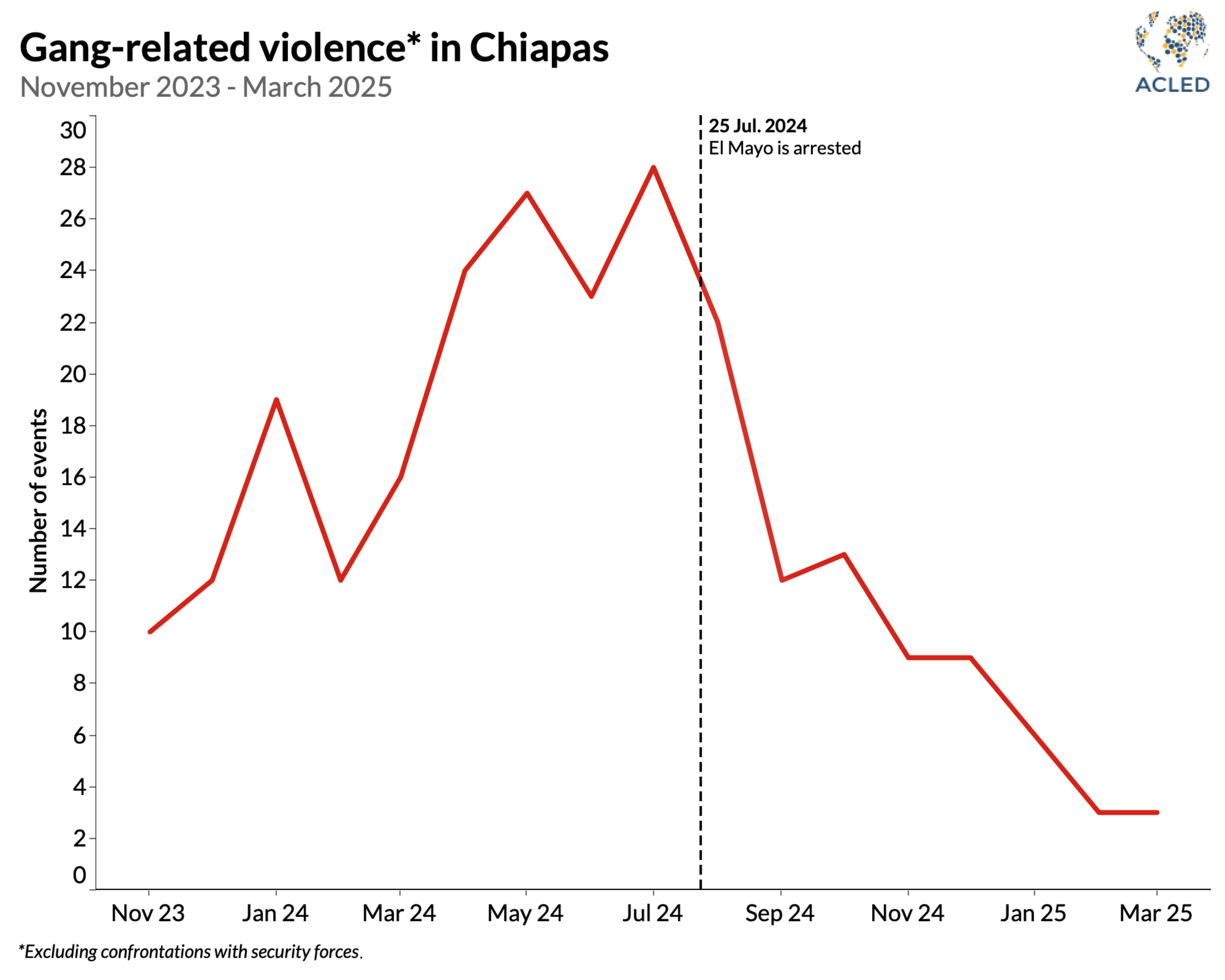

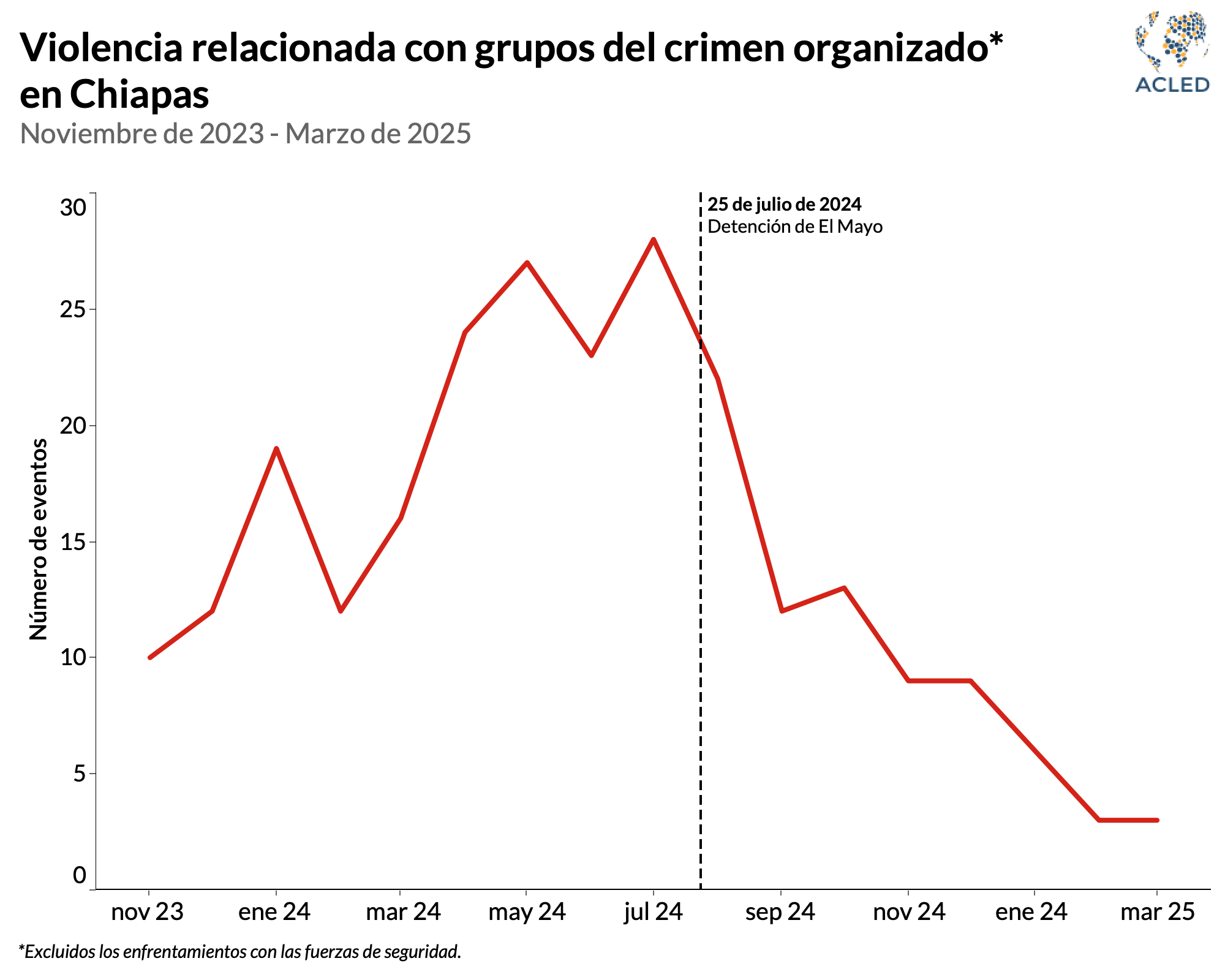

However, the CJNG’s behavior in other areas under dispute with the Sinaloa Cartel is not uniquely offensive. In Chiapas, gang-related violence decreased by 51% between 25 July 2024 and 31 March 2025 compared to the previous eight-month period (see graph below). This happened even though Chiapas has been the epicenter of a turf war between the two cartels over the control of migrant trafficking routes from Central America. While the decrease can be partly attributed to state-led efforts to curb insecurity and increased collaboration between state and military forces,26Online interview with Armando Rodríguez Luna, an expert on organized crime and security dynamics, ACLED, April 2025; Aristegui Noticias, “Chiapas | Authorities say intentional homicides have decreased by 63%,” 9 January 2025 (Spanish) the CJNG may also have adopted strategic patience; it is either waiting for the Sinaloa Cartel to weaken or is seeking an arrangement with local power brokers to preserve its key operations without resorting to violence. Part of the reason for this may be that the US designated the CJNG a foreign terrorist organization (FTO), alongside the Sinaloa Cartel and four other Mexican criminal groups, exposing the group to heightened scrutiny from the Mexican government. At the same time, it remains actively engaged in turf wars and clashes with security forces in the state of Michoacán, which provides an additional incentive for the CJNG to maintain a low profile and concentrate its efforts on high-priority fronts.

Nevertheless, Chiapas and other highly contested areas remain at risk of a violent escalation in conflict. In Zacatecas, violence has remained constant since the onset of the Sinaloa Cartel’s internecine conflict, despite the convergence of CJNG’s interest and territorial expansion in this state since 2020. As criminal dynamics shift, the CJNG might seek to take advantage of the redeployment of Cabrera Sarabia forces — a Sinaloa Cartel affiliate aligned with El Mayo — to neighboring Durango, where they are thought to support El Mayo against Los Chapitos.27Anabel Hernández, “All-out war: Los Chapitos bomb Golden Triangle,” Deutsche Welle, 1 November 2024 (Spanish)

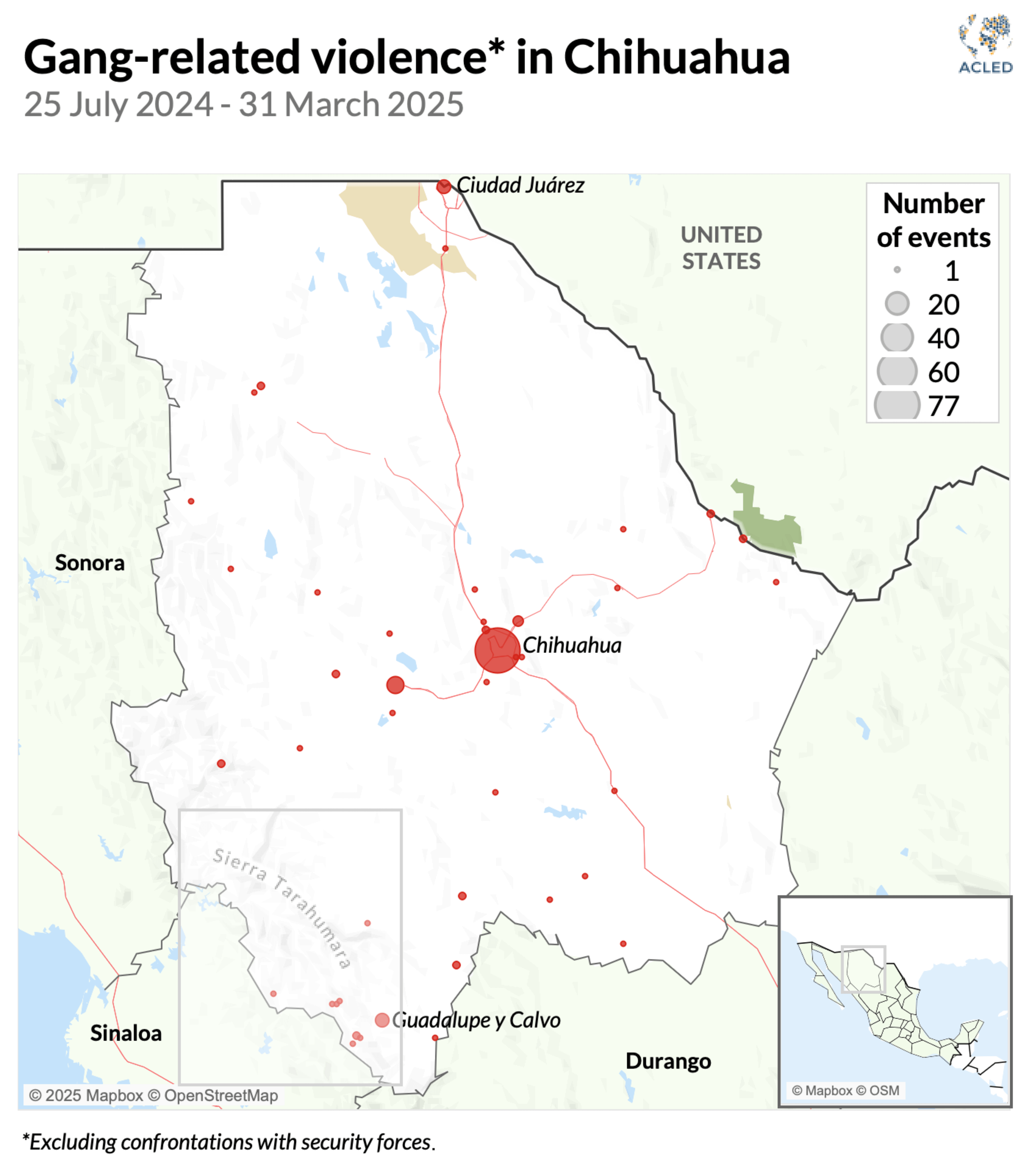

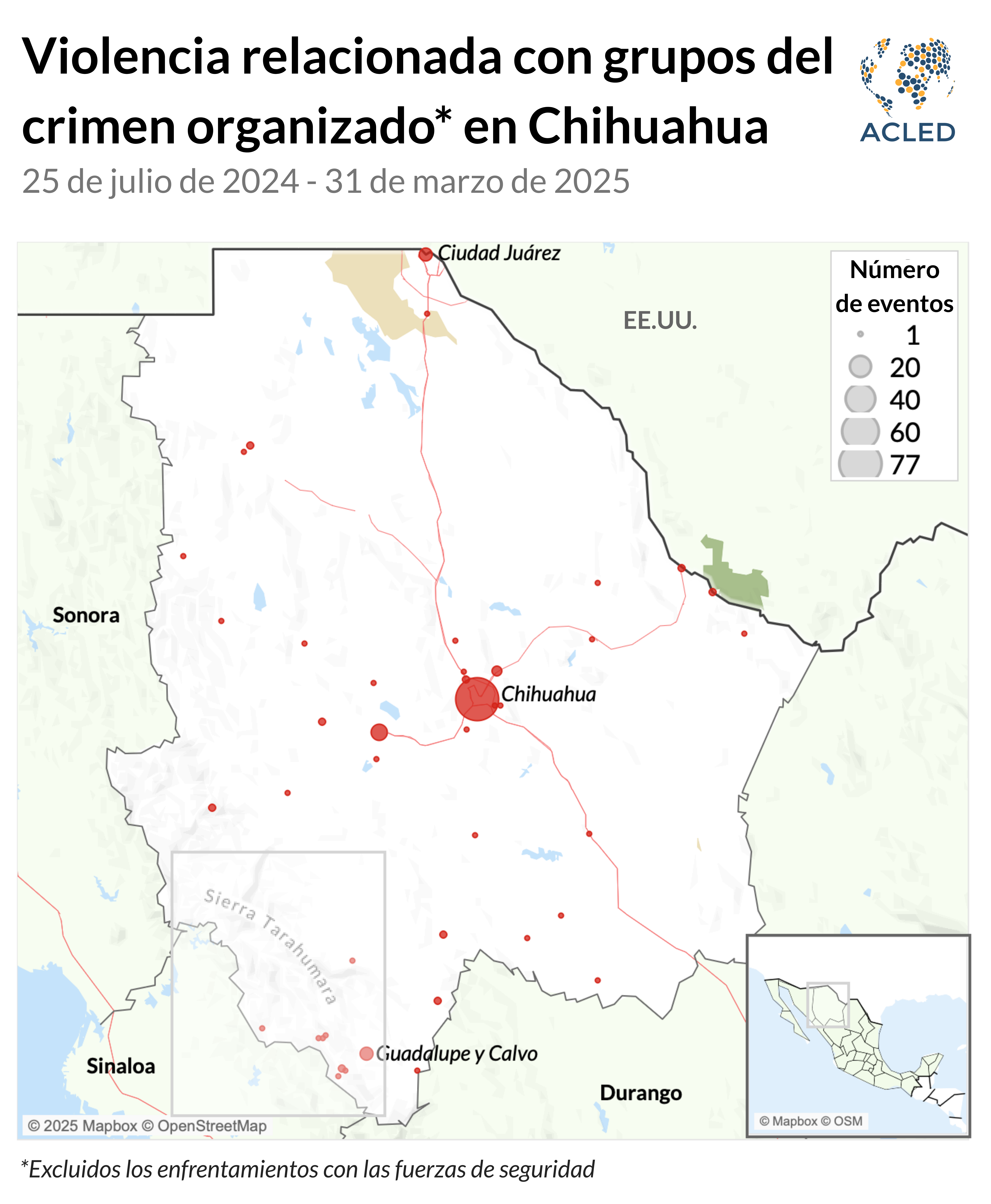

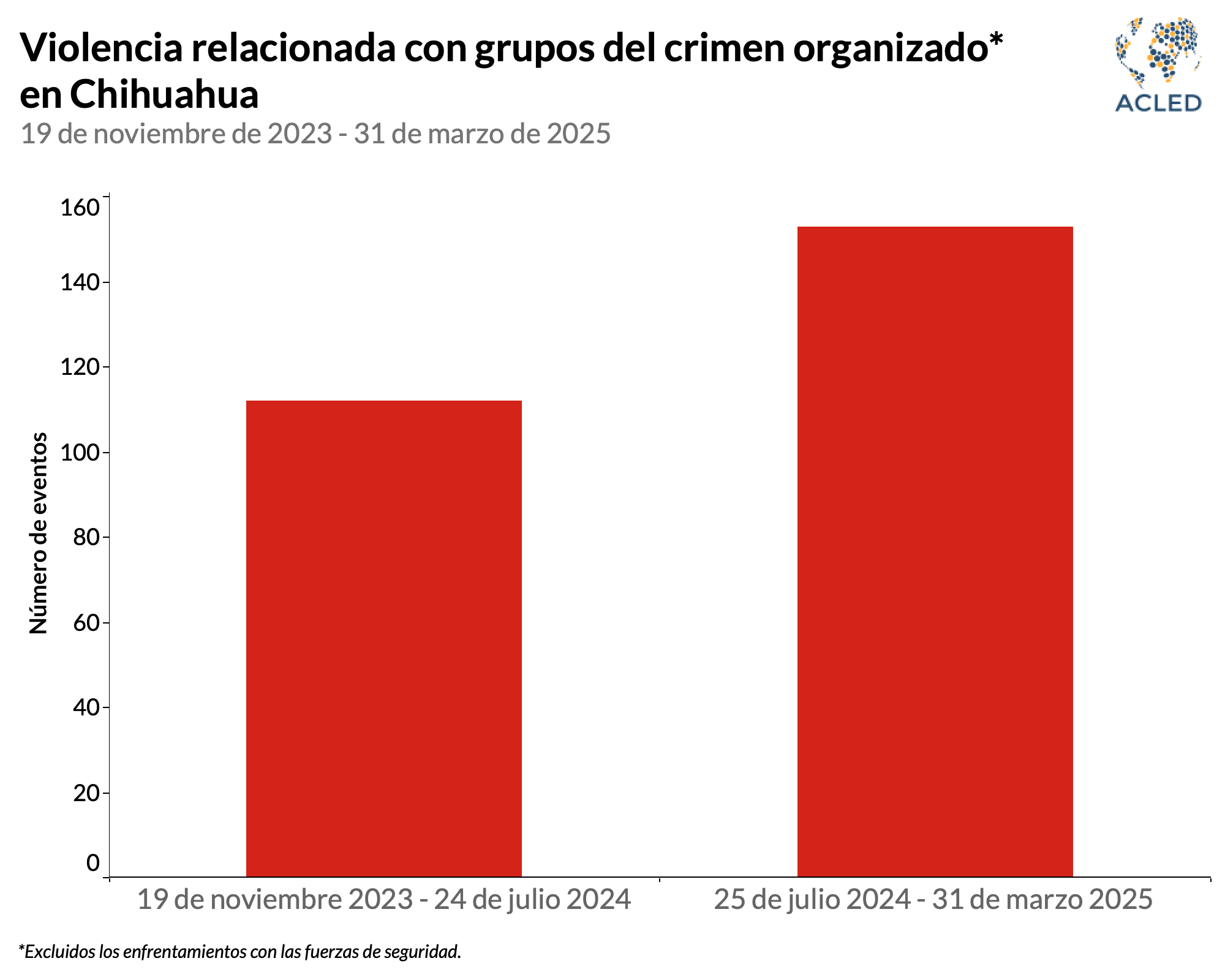

The CJNG is not the only criminal group likely to exploit the Sinaloa Cartel’s fragmentation. In Sonora, the cartel’s factions face pressure from the Sonora Independent Cartel, an alliance formed in 2023 by three Sinaloa Cartel offshoots to stop the cartel’s expansion.28Sol Prendido, “New Independent Cartel of Sonora vs. Los Chapitos,” Borderland Beat, 12 March 2024 Another group, La Línea, has reportedly taken advantage of the relocation of Sinaloa Cartel’s forces to Culiacán to intensify its incursion in Chihuahua against Los Salgueiro, a cell affiliated with the Sinaloa Cartel (see map and graph below).29Online interview with Armando Vargas and Yair Mendoza, security program coordinator and investigator at Mexico Evalúa, ACLED, April 2025 This drove a resurgence of violence and the displacement of local residents in the Sierra Tarahumara region, particularly in the Guadalupe y Calvo municipality.

State response: Is this the end of ‘Hugs, not Bullets’?

Upon taking office on 1 October, Sheinbaum inherited heightened violence levels that many have attributed to the security strategy of her predecessor and mentor, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), whose “Hugs, not Bullets” policy prioritized social programs and prevention over a militarized response. Shortly after coming to power, Sheinbaum unveiled her security plan.30Emilio Dorantes Galeana, “Claudia Sheinbaum’s Security Strategy,” Wilson Center, 9 October 2024 While Sheinbaum’s plan remains aligned with AMLO’s approach, domestic demands to contain the escalation of violence and US pressure to stem drug trafficking and migration flows have contributed to a change in tone from the federal government.

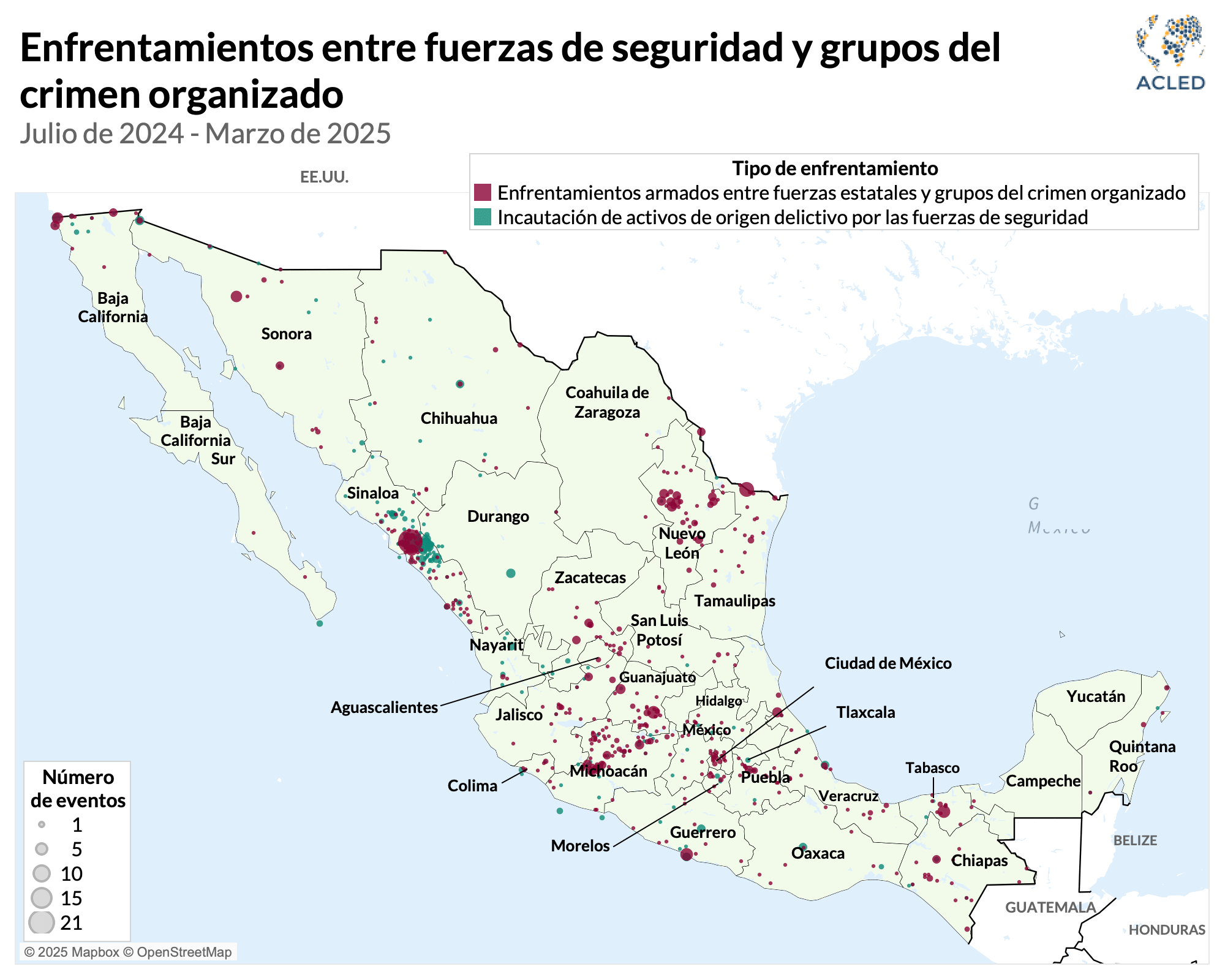

ACLED data from Sheinbaum’s first six months in office point to a change in trend. Armed confrontations between non-state armed groups and security forces experienced a 33% increase compared to the previous six months. This increase has remained largely confined to Sinaloa and has been driven by the internecine fighting in the Sinaloa Cartel, which prompted a heightened security response from state actors as early as September, well before Sheinbaum’s swearing-in. Initial efforts to contain the rise in violence in Sinaloa were followed by the government’s heavy-handed security response in the first quarter of 2025, during which clashes were concentrated in states bordering the US, especially in Nuevo León and Tamaulipas, and in traditional hotspots of violence such as Michoacán (see graph and map below). Armed clashes have further increased alongside intelligence-driven operations, which have been closely aligned with the federal security strategy, as is evidenced by a surge in the destruction of criminal assets such as narco laboratories, drugs, and surveillance systems.

The federal government’s response and the intensification thereof in the first quarter of 2025 were largely shaped by President Donald Trump taking office in January. He swiftly designated several Mexican criminal groups, including the Sinaloa Cartel and CJNG, as FTOs and pressured the Mexican government to curb migration and drug trafficking flows under the threat of tariffs on Mexican products.31Natalie Kitroeff and Paulina Villegas, “Trump Threats and Mexico’s Crackdown Hit Mexican Cartel,” The New York Times, 2 March 2025 The US pressure prompted the Mexican federal government to deploy 10,000 military and National Guard officers32Patricia San Juan Flores and Alejandro Santos Cid, “This is how Sheinbaum has distributed 10,000 soldiers on the border between Mexico and the United States,” El País, 5 February 2025 (Spanish) and to launch Operation Northern Border on 5 February. As a result of this security operation, Mexican authorities have reportedly arrested thousands of people and have seized over 1,900 weapons and 25 tonnes of drugs as of 3 April.33Secretaría de Seguridad y Protección Ciudadana, “The Security Cabinet of the Government of Mexico reports the results obtained from ‘Operation Northern Border’ on April 3, 2025,” 4 April 2025 (Spanish) The arrests of criminal group leaders conducted by the Mexican authorities in recent months suggest that the Mexican authorities may gradually mirror elements of the same kingpin strategy implemented under President Calderón’s administration, which consisted of taking down top leadership to dismantle criminal groups. Although these efforts may serve as a valuable bargaining chip in negotiations with the US, they have sparked debate about their efficacy in curbing organized crime and potentially contributing to further violence.

Criminal organizations may also be adapting their tactics to survive under pressure. In Sinaloa, the spike in clashes between security forces and armed groups since September 2024 has coincided with a decrease in gang-on-gang violence and targeting of civilians in the first quarter of 2025. Similarly, federal authorities highlighted a 27% decrease in intentional homicide between October 2024 and February 2025.34Ana Luisa Ochoa Ventura, “Homicides in Mexico decrease by 15%, but Sinaloa shows a different picture,” Debate Sinaloa, 12 March 2025 (Spanish) While these figures could be attributed to the success of security operations in the area and indicate a degree of de-escalation of the conflict, they also signal that criminal groups may have opted for other expressions of violence, such as forced disappearances, which have skyrocketed in Sinaloa in the first quarter of 2025 relative to the same period in 2024.35México Evalúa, “Alerta de inseguridad: las desapariciones incrementan en 20 estados,” March 2025; Javier Cabrera Martínez, “Sinaloa faces an alarming increase in disappearances; 911 cases in four months surpass a 16-year record,” El Universal, 25 March 2025 (Spanish) Other forms of pervasive criminal activity have begun gaining momentum in the state, including extortion, in order to finance the Sinaloa Cartel’s war. In practice, these shifts are indicative of the rapid adaptability of criminal groups and could well apply to other areas under intense security scrutiny.

There is also growing skepticism around the efficiency of operations targeting criminal assets, including the seizure of drug laboratories, which rarely lead to the arrests of members of criminal groups and are very likely to trigger the movement of those groups to establish their production operations elsewhere.36Online interview with InSight Crime, ACLED, March 2025 Alongside the reorganization of criminal groups, the concentration of security operations along Mexico’s northern border risks leaving other areas vulnerable to escalating criminal disputes, particularly in the country’s center and south.

Perhaps most strikingly, though, the arrest of Sinaloa Cartel leader El Mayo and the subsequent wave of violence between the cartel’s factions serve as an example of how these operations have the potential to lead to gang-on-gang violence. Further US pressure on criminal groups and possible demands for the arrest of high-profile leaders, particularly the CJNG and the Sinaloa Cartel, may foment further fragmentation with the potential to worsen levels of violence. As a result of the fragmentation of large groups, local criminal groups are likely to grow autonomous, which could lead to a new phase of violence.37Online interview with Armando Rodríguez Luna, an expert on organized crime and security dynamics, ACLED, April 2025

A violent escalation in the making

The fracture within the Sinaloa Cartel marks a structural turning point in Mexico’s criminal landscape. There are rising signs that it will have repercussions well beyond the cartel’s traditional strongholds. Some journalists have questioned whether the cartel as a cohesive identity will continue to exist.38Anayeli Tapia Sandoval, “The end of the big cartels? This is how organized crime has been reshaped in Mexico,” Infobae, 6 March 2025 (Spanish); Rubi Martinez, “These are the reasons why the Sinaloa Cartel no longer exists, according to Luis Chaparro,” Infobae, 28 November 2024 (Spanish) Another plausible outcome is the cartel’s deliberate excision of its weakened cells, allowing the organization to survive, albeit in a different form, as its internal structure and system of alliances shift.

As the Sinaloa Cartel is forced to draw on its resources to sustain its internal power struggle, it has become more vulnerable to external threats. Other groups, such as the CJNG, smaller criminal organizations, and newly formed alliances, could exploit the Sinaloa Cartel’s weakened position and continue their own territorial expansion. The Mexican press has reported that the CJNG might have forged a new alliance with Los Chapitos against El Mayo’s faction, with the aim of redistributing areas controlled by El Mayo.39Andrés Martínez, “The alliance between Los Chapitos and the CJNG has not been seen operating in Sinaloa, says Luis Chaparro,” Infobae, 2 January 2025 (Spanish) Other sources indicate that the CJNG might take its time before choosing a side as it waits for the factions to wear each other down.40Online interview with Daniel Weisz Argomedo, an expert on organized crime and security dynamics from Mexico, ACLED, April 2025 Either path signals a shift in criminal dynamics that could fuel further violence. However, the CJNG is not immune to pressure. The discovery of mass detention sites in Jalisco,41Mariana Fernández, “Killing Camp in Mexico Shows Horrors of CJNG Forced Recruitment,” Insight Crime, 25 March 2025 believed to belong to the CJNG, and increased scrutiny from US authorities suggest that its expansion may face growing obstacles, leaving space for local criminal actors to assert themselves more aggressively.

Meanwhile, under pressure from the Trump administration, the Mexican government appears to be responding to organized criminal activity and violence in the country using familiar kingpin-style strategies, which carry additional risks of further fragmenting the criminal landscape and creating power vacuums. In this volatile context, the security response has become part of the shifting dynamics, influencing territorial contests and emerging alliances. Along the northern border, which is strategic for trafficking activities, there are already signs that local criminal groups may be gaining in strength and autonomy. Sustained criminal disputes are likely to persist until a hegemonic force emerges.

A potential future scenario involves heightened risks for civilians, as violence threatens to reach new areas. The intensification of the conflict in Sinaloa has exposed civilians to heightened violence for siding with the wrong group and rising levels of extortion as criminal groups seek sources of revenue to finance their warfare. Were violence to spread further, the prospects for civilians would be gloomy. Similarly, political figures are particularly vulnerable to shifting power balances in their localities as armed groups seek to consolidate their territorial control through criminal governance and to mitigate law enforcement operations against their interests.

More concerning is the possibility that US pressure on security developments in Mexico could extend beyond threats of economic sanctions. The US ambassador to Mexico has not ruled out the possibility of concerted or unilateral US intervention on Mexican soil at a time when surveillance drone flights in Mexico are on the rise.42Dan De Luce, Ken Dilanian, and Courtney Kube, “Trump administration weighs drone strikes on Mexican cartels,” NBC News, 8 April 2025 Such a scenario would amount to a full-blown return to the kingpin strategy, an approach that has historically led to criminal groups’ splintering and intensified violence in contested and localized territories, the consequences of which may run against the Mexican government’s stated goals.

Visuals produced by Ana Marco and Ciro Murillo.

Cómo la fractura del Cártel de Sinaloa está redibujando el mapa del crimen en México

La detención de Ismael ‘‘El Mayo’’ Zambada en los Estados Unidos el 25 de julio de 2024 marcó un antes y un después para el Cártel de Sinaloa. En medio de tensiones latentes derivadas de anteriores interrupciones en su cúpula directiva, la detención de su antiguo líder ha desembocado en una guerra total entre dos de las facciones del cártel, Los Chapitos y El Mayo, hasta el punto que muchos han empezado a cuestionar la existencia continua del cártel. La ruptura ha llevado a un aumento de la violencia en el bastión del grupo en Sinaloa, pero también ha empezado a extenderse en territorios controlados y disputados por el Cártel de Sinaloa, ya que otros grupos criminales tratan de aprovechar la fractura para expandirse territorialmente. El estallido de los enfrentamientos y ataques en septiembre de 2024 tras la detención de El Mayo1Animal Político, “Sinaloa suma 19 homicidos y otros 80 crímines en medio de enfrentamientos del crimen organizado” 14 de septiembre de 2024 contribuyó a que en 2024 se registraran algunos de los niveles más altos de violencia con participación de grupos armados no estatales en México en los últimos seis años, y desde entonces, ha contribuido a mantener altos niveles de violencia en todo el país.

Ante conflictos preexistentes y emergentes, la presidenta Claudia Sheinbaum ha comenzado a implementar su nuevo plan de seguridad, que dió a conocer en la toma de protesta el 1 de octubre de 2024. La respuesta estatal bajo la administración Sheimbaum ha consistido en un mayor despliegue de fuerzas, en operaciones de inteligencia y detenciones de alto perfil. Estas acciones se han visto parcialmente influenciadas por las presiones renovadas de la administración Trump para reducir el tráfico de drogas y la migración, mientras los políticos estadounidenses contemplan ataques militares unilaterales contra organizaciones criminales en México. Aunque está todavía en su fase inicial, existen pocos indicios de que estos esfuerzos hayan debilitado significativamente a los grupos criminales. Por el contrario, las medidas que está adoptando el gobierno sugieren que podría estar volviendo a poner en práctica la estrategia de perseguir a líderes criminales conocida como “kingpin strategy” utilizada por el presidente Felipe Calderón para derrocar a los principales líderes de los grupos criminales, lo que corre el riesgo de alimentar el surgimiento de actores criminales oportunistas.

Las consecuencias de la disputa del Cártel de Sinaloa han desencadenado una realineación más amplia de los grupos criminales y la apertura de nuevos conflictos en territorios disputados. Para entender la importancia de la fractura del Cártel de Sinaloa y su repercusión en las dinámicas de violencia entre bandas, es necesario comprender cómo ha llegado a tener tanta influencia y cómo su estructura interna ha permitido su expansión por todo el país.

El Cártel de Sinaloa: sus operaciones y sus divisiones internas

El Cártel de Sinaloa, uno de los grupos criminales más grande de México, tiene une estructura federal que permite a sus facciones y aliados mantener plena autonomía de funcionamiento y relaciones horizontales sin una jerarquía rígida.2InSight Crime, “Sinaloa Cartel,” 15 de marzo de 2024 A principios de la década de 1990, el Cártel de Sinaloa consolidó sus operaciones bajo el liderazgo de exmiembros del fracturado Cártel de Guadalajara: Joaquín Guzmán, conocido como ‘‘El Chapo’’, Ismael ‘‘El Mayo’’ Zambada y Juan José ‘‘El Azul’’ Esparragoza.3Samantha Pérez Dávila y Laura H. Atuesta Becerra, “Fragmentación y cooperación: la evolución del crimen organizado en México,” Programa de Política de Drogas, 2016, p. 19 La organización criminal dirigida por estos tres líderes estableció sus bastiones en los estados de Sinaloa, Durango y Chihuahua, particularmente en la zona montañosa conocida como el ‘‘Tríangulo dorado’’, donde el cártel controla los cultivos de amapola y marihuana.4BBC, “Qué es el “Triángulo Dorado”, la zona donde se lleva a cabo el operativo militar que rastrea a El Chapo Guzmán” 17 de octubre de 2015 Con el tiempo, el cártel diversificó sus actividades criminales, implicándose en la producción de drogas sintéticas, la extorsión de industrias agrícolas y otros negocios legales e ilegales.5La Vanguardia MX, “Asfixia el crimen organizado a productores agrícolas en Sinaloa,” 16 de febrero de 2025; Andrés Martínez, “Tentáculos del Cártel de Sinaloa llegan a 35 comercios legales, según Edgardo Buscaglia,” Infobae, 12 de julio de 2024 Aunque estos estados han sido cruciales para las operaciones, el cártel también ha forjado alianzas con grupos criminales locales para expandir su influencia en zonas estratégicas que conectan con la frontera norte, en los estados de Sonora y Baja California, y con el sur, en los estados de Chiapas y Quintana Roo.

El liderazgo del cártel se ha tambaleado en varias ocasiones, en particular tras las detenciones de dos líderes históricos del cártel y del presunto fallecimiento de El Azul en 2014, lo que llevó a realineamientos entre las diferentes facciones.6Anyeli Tapia Sandoval, “¿Qué pasó con Juan José Esparragoza, ‘El Azul’, y por qué EEUU lo sigue buscando aunque se dice que murió?” Infobae, 29 de octubre de 2024 En 2016, las autoridades mexicanas arrestaron a El Chapo, quien posteriormente fue extraditado a Estados Unidos en 2017.7InSight Crime, “Joaquín Guzmán Loera, alias ‘El Chapo,’” 29 de marzo de 2019 Más recientemente, el 25 de julio de 2024, El Mayo fue detenido en Estados Unidos junto con Joaquín Guzmán López, uno de los hijos de El Chapo.8France 24, “La caída de ‘El Mayo’ Zambada: ¿cómo se logró la captura del poderoso narco?” 31 de julio de 2025 Tras las detenciones de estas figuras de alto perfil, el liderazgo de las facciones del cártel se ha transferido a sus familiares.

Actualmente, el cártel está formado por dos facciones principales, ambas relacionadas con los miembros fundadores del cártel. La facción liderada por los hijos de El Chapo, conocidos como Los Chapitos, opera principalmente en Sinaloa y tiene una presencia sólida en el municipio de Culiacán y en la costa del Pacífico del estado, así como en Sonora y Baja California (véase el mapa a continuación), donde se han disputado el control del territorio con grupos rivales.

La información sobre la presencia del Cártel de Sinaloa y sus afiliados y las facciones del cártel por estado proviene del proyecto NarcoData (2020), Mexico Violence Resource Project (2021) y X @laloguerrero, 27 de julio de 2024.

A efectos del presente informe, los grupos afiliados al Cártel de Sinaloa se determinan a partir del análisis de redes de Nathan P. Jones, et al., ‘‘A Social Network Analysis of Mexico’s Dark Network Alliance Structure’’, Journal of Strategic Security, 2022, p.7, complementado con información más reciente sobre afiliaciones a bandas.

El Mayo lideró la otra facción principal. Después de su detención, quedó bajo el control de uno de sus hijos, conocido como ‘‘El Mayito Flaco’’.9Gustavo Castillo García, “El Mayito Flaco, el sucesor al frente del cártel: DEA,” La Jornada, 27 de julio de 2024 La facción El Mayo domina las operaciones en Durango y las zonas rurales de Sinaloa y cuenta con una presencia sólida en Baja California, Sonora y Zacatecas.

Otros grupos han formado parte de la federación de cárteles y, en ocasiones, han competido con las facciones de Los Chapitos y El Mayo. En particular, las facciones y células que han mantenido vínculos relevantes con los líderes fundadores del cártel son el grupo criminal Gente del Guano, liderado por el hermano de El Chapo, Aureliano Guzmán Loera, conocido como ‘‘El Guano’’, y otro liderado por la familia Cabrera Sarabia, socios tradicionales de El Mayo.10Daniel Wachauf, “‘Escapa ‘El Guano’, hermano de ‘El Chapo’ Guzmán, durante detención de su jefe de seguridad el ‘R8’” El Universal, 9 de julio de 2024; Miguel Flores, “De ser amigo de ‘Los Chapitos’ a ponerlos en jaque en EEUU: así es la historia criminal de ‘El Mini Lic’” Infobae, 14 de diciembre de 2024; Ernesto Jiménez, “Así inició la alianza entre los Zambada y los Cabrera Sarabia, el grupo que pelea la guerra contra Los Chapitos,” Infobae, 4 de enero de 2025

En virtud de su estructura federal y su sistema de alianzas, el Cártel de Sinaloa ha sido capaz de consolidar su presencia en varios estados, en particular en la frontera norte. Sin embargo, su presencia a lo largo de este estratégico corredor de tráfico ha generado constantemente rivalidades, ya que otras organizaciones criminales han intentado aprovechar las tensiones internas del cártel para desafiar su hegemonía en su bastión. Aunque el cártel logró mantener una relativa unidad, la detención de El Mayo, de la que sus partidarios culpan a los hijos de El Chapo, marcó un punto de inflexión. Alegan que el líder de Los Chapitos, Joaquín Guzmán López, traicionó a El Mayo ante las autoridades estadounidenses con la esperanza de obtener ventajas para él mismo y su hermano, Ovidio Guzmán López. Ambos se enfrentan a cargos en EE.UU.11Elías Camhaji, “La caída de ‘El Mayo’ Zambada: cronología del escándalo que ha cimbrado a México,” El País, 21 de febrero de 2025; Luis Chaparro, “Desde la cárcel el “Chapo” Guzmán planeó con Estados Unidos el secuestro del ‘Mayo,’” Proceso, 4 de noviembre de 2024 La disputa desató una guerra abierta que amenaza la estabilidad de la federación.

La guerra territorial entre facciones de Sinaloa se extiende por el bastión del cártel

La presunta traición de Los Chapitos desencadenó un conflicto abierto contra la facción de El Mayo en Sinaloa, el epicentro de la pugna. Aunque el cártel había atravesado disputas internas en el pasado, El Mayo y otros líderes del cártel eran conocidos por su papel de mediadores ayudando a reducir el riesgo de conflicto directo entre las facciones.12Valentín Pereda and David Décary-Hetu, “Illegal Market Governance and Organized Crime Groups’ Resilience: A Study of The Sinaloa Cartel,” The British Journal of Criminology, marzo de 2024, p. 333 Tras un período de ajuste después de la detención de El Mayo en julio de 2024, durante el cual se produjeron incidentes violentos limitados que involucraron a miembros rivales del cártel, las facciones protagonizaron una nueva oleada de enfrentamientos y ataques que inició formalmente el 9 de septiembre. Entre julio de 2024 y marzo de 2025, los ataques de grupos criminales contra civiles y los enfrentamientos entre grupos del crimen organizado casi se cuadruplicaron en comparación con el período entre el 19 de noviembre de 2023 al 24 de julio de 2024, los ocho meses anteriores, alcanzando su punto más alto en octubre y noviembre. La violencia alcanzó niveles nunca vistos en este estado desde que ACLED comenzó a cubrir México en 2018.

La escalada del conflicto parece estar impulsada por los intereses de la facción de El Mayo en aumentar su control en los pueblos y ciudades a lo largo de la costa, donde la facción de Los Chapitos ha mantenido mayor influencia, para ampliar el alcance de sus operaciones, que tradicionalmente se han concentrado en zonas limítrofes con el Estado de Durango.13Anabel Hernández, “Guerra sin cuartel: Los Chapitos bombardean Triángulo Dorado,” Deutsche Welle, 1 de noviembre de 2024 Las acciones violentas en Sinaloa se han concentrado principalmente en la capital del estado, Culiacán, que incluso antes del estallido del conflicto, fue el lugar de disputas entre estas facciones y grupos más pequeños que lucharon por el control de las operaciones de extorsión y del mercado local de drogas.14InSight Crime, “The Chapitos’ Monopoly on Drug Sales in Culiacán, Sinaloa,” 6 de diciembre de 2022 Sin embargo, la violencia desde entonces se ha extendido a zonas rurales del municipio de Culiacán y otros municipios del sur, a medida que las facciones intentan redibujar los límites de sus respectivas zonas de influencia. En particular, tras la detención de El Mayo, la violencia se ha intensificado en el sur, a lo largo de la costa del Pacífico, siguiendo las principales carreteras del estado, incluidas las carreteras federales 15 y 15D que conectan Culiacán con la segunda ciudad principal, Mazatlán, que cuenta con un importante puerto turístico y comercial controlado por el cártel (véase el mapa a continuación).15US Department of Justice Drug Enforcement Administration, “National Drug Threat Assessment 2024,” mayo de 2024, p. 8

Sinaloa se ha convertido en el escenario de niveles alarmantes de violencia contra civiles. ACLED registra un número alto de asesinatos desde septiembre, algo que contradice la reputación del Cártel de Sinaloa de utilizar una violencia menos abierta contra la población civil.16Valentín Pereda and David Décary-Hetu, “Illegal Market Governance and Organized Crime Groups’ Resilience: A Study of The Sinaloa Cartel,” The British Journal of Criminology, marzo de 2024, p. 338 Los civiles han sido blanco de ataques en represalia por sus presuntos vínculos con alguna de las facciones rivales. Los secuestros y desapariciones forzadas han ido también en aumento, ya que estos grupos intentan infundir miedo y extorsionar a los familiares para que paguen sus rescates.17Amílcar Salazar Méndez, “Guerra entre Chapitos y Mayiza desata ola de desapariciones y extorsiones,” Milenio, 29 de diciembre de 2024

Las muestras públicas de violencia y los ataques selectivos contra figuras destacadas consideradas vinculadas o críticas de los líderes del cártel, incluidos influencers de redes sociales, han servido para exhibir la fuerza de las distintas facciones e intimidar a sus seguidores.18Entrevista en línea con Daniel Weisz Argomedo, experto en crimen organizado y dinámicas de seguridad, ACLED, abril de 2025; El Imparcial, “‘Chapitos” vs “Mayitos’: Estos son los 6 influencers asesinados en la guerra interna del Cartel de Sinaloa” 29 de marzo de 2025 (Spanish) Las facciones también han dirigido sus ataques a políticos y autoridades políticas para establecer el control sobre localidades y disminuir la influencia política de sus rivales. Desde la detención de El Mayo el 25 de julio de 2024, ACLED registra al menos diez ataques dirigidos contra figuras políticas en Sinaloa, algunos de los cuales se cree que tienen vínculos con una de las facciones del cártel.19Sonora Presente, “El líder ganadero de Sinaloa que fue asesinado por ser un operador financiero del Mayo Zambada,” 3 de octubre de 2024 El número de estos ataques supera los niveles registrados en los ocho meses anteriores en un estado donde la relativa hegemonía del Cártel de Sinaloa contribuyó a que se produjeran menos ataques, incluso en periodos electorales.

Más allá de Sinaloa, las guerra territorial del cártel también ha afectado a Sonora y Baja California, donde se intensificaron las disputas en curso entre aliados de cada facción implicados en el tráfico transfronterizo de drogas, armas y personas.20Anel Tello, “Los Rusos y Los Chapitos: las aristas de su disputa por San Luis Río Colorado,” Milenio, 21 de marzo de 2024; Rubi Martínez, “¿Es de Los Chapitos o de ‘El Mayo’ Zambada? Hallan ‘narcotúnel’ en Sonora cerca de la frontera de EEUU | FOTOS,” Infobae, 3 de mayo de 2024 Tras el estallido de las luchas intestinas a raíz de la detención de El Mayo, la violencia en los municipios vecinos de San Luis Río Colorado, en Sonora, y Mexicali, en Baja California, se ha intensificado en medio de disputas entre Los Rusos (aliados de El Mayo), Los Chapitos y Los Salazar (antiguo socio de Los Chapitos) (véase el gráfico a continuación).21Ernesto Jiménez, “Este es el origen de Los Rusos, uno de los principales aliados del Mayito Flaco en la guerra contra Los Chapitos,” Infobae, 11 de septiembre de 2024

También hay indicios crecientes de que la disputa entre facciones rivales podría estar extendiéndose a otras zonas, como el estado de Durango, donde los niveles de violencia han sido relativamente bajos en los últimos años.22Entrevistas en línea con Daniel Weisz Argomedo y Armando Rodríguez Luna, expertos en crimen organizado y dinámicas de seguridad, ACLED, abril de 2025 En los ocho meses posteriores a la detención de El Mayo, los ataques y explosiones perpetrados por grupos armados no estatales han aumentado, potenciados por el mayor uso de drones. ACLED registra al menos quince acciones por grupos armados, incluyendo el uso de un drone cargado con explosivos,23Andrés Martínez, “Tiran explosivos con drones en comunidad de Eldorado, Sinaloa, denuncian habitantes,” Infobae, 8 de noviembre de 2024 más del doble que el número de eventos registrados en los ocho meses precedentes.

Las organizaciones criminales rivales buscan explotar la fractura del Cártel de Sinaloa

Las consecuencias de la ruptura del Cártel de Sinaloa se extienden más allá de las dinámicas internas a medida que otros grupos criminales aprovechan las limitadas capacidades operativas del cártel para avanzar territorialmente o forjar nuevas alianzas.24Ernesto Jiménez, “El CJNG podría aprovechar la división del Cártel de Sinaloa para atacar sus territorios, afirma José Reveles,” Infobae, 6 September 2024

Uno de los grupos que aparentemente busca sacar provecho de la ruptura interna del Cártel de Sinaloa es su principal rival, el Cártel de Jalisco Nueva Generación (CJNG). Desde la fractura del Cártel de Sinaloa, los datos de ACLED apuntan hacia una intensificación del conflicto entre los dos cárteles en zonas de actividades ilícitas. Un ejemplo notable es Tijuana, Baja California, donde los enfrentamientos entre los grupos armados no estatales y sus ataques contra civiles aumentaron un 16 % entre el 25 de julio de 2024 y el 31 de marzo de 2025, en comparación con los ocho meses anteriores. El repunte ha afectado especialmente a las delegaciones del norte de la ciudad, a lo largo de la frontera con Estados Unidos, donde el Cártel de Sinaloa y otros grupos criminales —incluidos el Cártel de Tijuana y el CJNG, que se ha expandido en el estado al menos desde 201425Michael Lettieri, “Mapping Criminal Organizations in Mexico,” Mexico Violence Resource Project, 2021 — compiten por el control de las actividades de tráfico transfronterizo en este corredor crítico. Dinámicas similares están en juego en Manzanillo, Colima, donde la disputa entre el CJNG y el Cártel de Sinaloa por el control del puerto —un centro clave para el tráfico de drogas— se ha intensificado. Mientras tanto, en el municipio de Huajicori, Nayarit, la facción El Mayo del Cártel de Sinaloa y el CJNG han tratado de asegurar la ruta que conecta el estado de Sinaloa con Zacatecas, un enlace crucial entre la costa del Pacífico y el corredor de tráfico del norte. La escalada de la violencia en zonas localizadas y altamente estratégicas sugiere un esfuerzo deliberado para concentrar su poder de guerra y afirmar el dominio en puntos vitales del tráfico.

Sin embargo, la actitud del CJNG en otras zonas disputadas con el Cártel de Sinaloa no es únicamente ofensiva. En Chiapas, la violencia relacionada con el crimen organizado disminuyó un 51 % entre el 25 de julio de 2024 y el 31 de marzo de 2025 en comparación con el periodo de ocho meses anterior (véase el gráfico a continuación). Esto ocurrió a pesar de que Chiapas ha sido el epicentro de una guerra territorial entre los dos cárteles por el control de las rutas de tráfico de migrantes procedentes de Centroamérica. Aunque este descenso puede atribuirse en parte a los esfuerzos del estado por frenar la inseguridad y a una mayor colaboración entre las fuerzas estatales y militares,26Entrevista en línea con Armando Rodríguez Luna, experto en crimen organizado y dinámicas de seguridad ACLED, abril de 2025; Aristegui Noticias, “Chiapas | Autoridades aseguran que homicidios dolosos disminuyeron 63%,” 9 de enero de 2025 el CJNG también puede haber optado por mantener paciencia estratégica; o bien está esperando a que el Cártel de Sinaloa se debilite, o bien está buscando un acuerdo con los agentes de poder locales para preservar sus operaciones clave sin recurrir a la violencia. En parte, esto puede deberse a que Estados Unidos designó al CJNG como organización terrorista extranjera, junto con el Cártel de Sinaloa y otros cuatro grupos criminales mexicanos, lo que expone al grupo a un mayor escrutinio por parte del gobierno mexicano. Al mismo tiempo, el CJNG sigue participando activamente en guerras territoriales y enfrentamientos con las fuerzas de seguridad en el estado de Michoacán, lo que supone un incentivo adicional para que mantenga un perfil bajo y concentre sus esfuerzos en frentes de alta prioridad.

No obstante, Chiapas y otras zonas muy disputadas siguen corriendo el riesgo de una escalada violenta del conflicto. En Zacatecas, la violencia se ha mantenido constante desde el inicio del conflicto intestino del Cártel de Sinaloa, a pesar de la convergencia de intereses del CJNG y su expansión territorial en este estado desde 2020. Al cambiar la dinámica criminal, el CJNG podría tratar de aprovechar el redespliegue de las fuerzas de Cabrera Sarabia — una facción del Cártel de Sinaloa alineada con El Mayo — hacia el vecino estado de Durango, donde se cree que apoyan a El Mayo contra Los Chapitos.27Anabel Hernández, “Guerra sin cuartel: Los Chapitos bombardean Triángulo Dorado,” Deutsche Welle, 1 de noviembre de 2024

El CJNG no es el único grupo criminal susceptible de explotar la fragmentación del Cártel de Sinaloa. En Sonora, las facciones del cártel se enfrentan a presiones por parte del Cártel Independiente de Sonora, una alianza formada en 2023 por tres escisiones del Cártel de Sinaloa para frenar su expansión.28Sol Prendido, “New Independent Cartel of Sonora vs. Los Chapitos,” Borderland Beat, 12 de marzo de 2024 Otro grupo, La Línea, ha aprovechado, según se informa, la reubicación de fuerzas del Cártel de Sinaloa a Culiacán para intensificar su incursión en Chihuahua contra Los Salgueiro, una célula afiliada al Cártel de Sinaloa (véase el mapa y el gráfico a continuación).29Entrevista en línea con Armando Vargas y Yair Mendoza, coordinador del programa de seguridad e investigador de México Evalúa, ACLED, abril de 2025 Esto provocó un resurgimiento de la violencia y del desplazamiento de los habitantes locales en la región de la Sierra Tarahumara, en particular en el municipio de Guadalupe y Calvo.

Respuesta del Estado: ¿es el fin de ‘‘Abrazos, no balazos’’?

Al tomar posesión el 1 de octubre, Sheinbaum heredó elevados niveles de violencia que muchos han atribuido a la estrategia de seguridad de su predecesor y mentor, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), cuya política de ‘‘Abrazos, no balazos’’ priorizó los programas sociales y la prevención sobre una respuesta militarizada. Poco después de llegar al poder, Sheinbaum dio a conocer su plan de seguridad.30Emilio Dorantes Galeana, “Claudia Sheinbaum’s Security Strategy,” Wilson Center, 9 de octubre de 2024 Aunque el plan de Sheinbaum sigue alineado con el enfoque de AMLO, las exigencias nacionales para contener la escalada de violencia y la presión estadounidense para frenar el narcotráfico y los flujos migratorios ha contribuido a un cambio de tono del gobierno federal.

Los datos de ACLED sobre los primeros seis meses de gobierno apuntan a un cambio de tendencia. Los enfrentamientos armados entre los grupos armados no estatales y las fuerzas de seguridad experimentaron un aumento del 33 % en comparación con los seis meses anteriores. Este aumento se ha concentrado en gran medida a Sinaloa y se ha visto impulsado por los enfrentamientos internos del cártel de Sinaloa, que provocaron una respuesta de seguridad reforzada por parte de las fuerzas del Estado ya en septiembre, antes de la toma de posesión de Sheinbaum. Los esfuerzos iniciales para contener el aumento de la violencia en Sinaloa fueron seguidos por una respuesta de seguridad intensificada por parte del gobierno en el primer trimestre de 2025, durante el cual los enfrentamientos se concentraron en los estados fronterizos con EE.UU., en particular en Nuevo León y Tamaulipas, y en focos tradicionales de violencia como Michoacán (véase gráfico y mapa a continuación). Los enfrentamientos armados han aumentado junto con las operaciones de inteligencia, que se han alineado estrechamente con la estrategia de seguridad federal, como demuestra el aumento de la destrucción de activos criminales como narcolaboratorios, drogas y sistemas de vigilancia.

La respuesta del gobierno federal y la intensificación de la misma en el primer trimestre de 2025 se han visto condicionadas en gran medida por la investidura de Donald Trump en enero. Trump designó rápidamente a varios grupos criminales mexicanos, entre ellos el Cártel de Sinaloa y el CJNG, como organizaciones terroristas extranjeras y presionó al gobierno mexicano para que frenara los flujos migratorios y de narcotráfico bajo la amenaza de imponer aranceles a los productos mexicanos.31Natalie Kitroeff and Paulina Villegas, “Trump Threats and Mexico’s Crackdown Hit Mexican Cartel,” The New York Times, 2 de marzo de 2025 La presión estadounidense llevó al gobierno federal mexicano a desplegar 10.000 militares y agentes de la Guardia Nacional32Patricia San Juan Flores and Alejandro Santos Cid, “Así ha repartido Sheinbaum a 10.000 militares en la frontera entre México y Estados Unidos,” El País, 5 de febrero de 2025 y a lanzar la Operación Frontera Norte el 5 de febrero. Como resultado de esta operación de seguridad, las autoridades mexicanas han detenido a miles de personas y se han incautado más de 1 900 armas y 25 toneladas de drogas, a fecha de 3 de abril.33Secretaría de Seguridad y Protección Ciudadana, “El Gabinete de Seguridad del Gobierno de México informa los resultados obtenidos de la ‘Operación Frontera Norte’ el día 03 de abril de 2025” 4 de abril de 2025 Las detenciones de líderes de grupos criminales por parte de las autoridades mexicanas en los últimos meses sugieren que podrían estar adoptando gradualmente elementos de la misma estrategia kingpin implementada bajo la administración del presidente Calderón, que consistía en desmantelar a los grupos criminales mediante la neutralización de sus líderes. Aunque estos esfuerzos pueden servir como una valiosa moneda de cambio en las negociaciones con Estados Unidos, han suscitado un debate sobre su eficacia para frenar el crimen organizado y su posible contribución a une escalada de la violencia.

Las organizaciones criminales pueden estar adaptando también sus tácticas para sobrevivir bajo la presión. En Sinaloa, el aumento de los enfrentamientos entre las fuerzas de seguridad y los grupos armados desde septiembre de 2024 ha coincidido con un descenso de la violencia entre grupos criminales y de los ataques contra civiles en el primer trimestre de 2025. Del mismo modo, las autoridades federales destacaron un descenso del 27 % en los homicidios dolosos entre octubre de 2024 y febrero de 2025.34Ana Luisa Ochoa Ventura, “Disminuye 15% homicidios en México, pero Sinaloa muestra otro panorama,” Debate Sinaloa, 12 de marzo de 2025 Si bien estas cifras podrían atribuirse al éxito de las operaciones de seguridad en la zona e indican cierto grado de desescalada del conflicto, también señalan que los grupos criminales pueden haber optado por otras expresiones de violencia, como las desapariciones forzadas, que se han disparado en Sinaloa en el primer trimestre de 2025 en relación con el mismo periodo de 2024.35México Evalúa, “Alerta de inseguridad: las desapariciones incrementan en 20 estados,” marzo de 2025; Javier Cabrera Martínez, “Sinaloa enfrenta aumento alarmante en desapariciones; 911 casos en cuatro meses superan cifras históricas de 16 años,” El Universal, 25 de marzo de 2025 Otras formas de actividad criminal generalizada han empezado a adquirir importancia en el estado, incluida la extorsión, para financiar la guerra del Cártel de Sinaloa. En la práctica, estos cambios son indicativos de la rápida adaptabilidad de los grupos criminales y bien podrían aplicarse a otras áreas que se encuentran bajo intenso escrutinio en materia de seguridad.

También existe un creciente escepticismo en torno a la eficacia de las operaciones dirigidas contra activos de origen criminal, incluida la incautación de laboratorios de drogas, que rara vez conducen a la detención de miembros de grupos criminales y que es muy probable que desencadenen el desplazamiento de dichos grupos para establecer sus operaciones de producción en otros lugares.36Entrevista en línea con InSight Crime, ACLED, marzo de 2025 Junto a la reorganización de los grupos criminales, la concentración de las operaciones de seguridad a lo largo de la frontera norte de México corre el riesgo de dejar otras zonas vulnerables a la escalada de las disputas criminales, especialmente en el centro y el sur del país.

Sin embargo, lo más llamativo es que la detención del líder del Cártel de Sinaloa, El Mayo, y la posterior oleada de violencia entre las facciones del cártel sirven de ejemplo de cómo estas operaciones pueden desembocar en violencia entre grupos del crimen organizado. Una mayor presión de los Estados Unidos sobre los grupos criminales y las posibles órdenes de detención de líderes destacados, en particular del CJNG y del Cártel de Sinaloa, pueden fomentar una mayor fragmentación con el potencial de empeorar los niveles de violencia. Como consecuencia de la fragmentación de los grandes grupos, es probable que los grupos criminales locales adquieran mayor autonomía, lo que podría dar lugar a una nueva fase de violencia.37Entrevista en línea con Armando Rodríguez Luna, experto en crimen organizado y dinámicas de seguridad, ACLED, abril de 2025

Una escalada violenta en ciernes

La fractura del Cártel de Sinaloa marca un punto de inflexión estructural en el panorama criminal de México. Hay señales crecientes de que tendrá repercusiones mucho más allá de los bastiones tradicionales del cártel. Algunos periodistas han puesto en duda que el cártel siga existiendo como identidad cohesionada.38Anayeli Tapia Sandoval, “¿El fin de los grandes cárteles? Así es como el crimen organizado se ha reconfigurado en México,” Infobae, 6 de marzo de 2025; Rubi Martinez, “Éstas son las razones por las que el Cártel de Sinaloa ya no existe, según Luis Chaparro,” Infobae, 28 de noviembre de 2024 Otro resultado plausible es la escisión deliberada por parte del cártel de sus células debilitadas, lo que permitiría a la organización sobrevivir, aunque en una forma diferente, al cambiar su estructura interna y su sistema de alianzas.

A medida que el Cártel de Sinaloa se ve obligado a utilizar sus recursos para mantener su lucha interna por el poder, se ha vuelto más vulnerable a las amenazas externas. Otros grupos, como el CJNG, organizaciones criminales más pequeñas, y nuevas alianzas, pueden explotar el debilitamiento de la posición del Cártel de Sinaloa y continuar su propia expansión territorial. La prensa mexicana ha informado que el CJNG podría haber forjado una nueva alianza con Los Chapitos contra la facción El Mayo, con el objetivo de redistribuir las zonas controladas por El Mayo.39Andrés Martínez, “Alianza entre Los Chapitos y el CJNG no se ha visto operando en Sinaloa, afirma Luis Chaparro,” Infobae, 2 de enero de 2025 Otras fuentes indican que el CJNG podría tomarse su tiempo antes de elegir un bando, a la espera de que las facciones se desgasten entre sí.40Entrevista en línea con Daniel Weisz Argomedo, experto en crimen organizado y dinámicas de seguridad de México, ACLED, abril de 2025 Cualquiera de las vías indica un cambio en las dinámicas criminales que pueda alimentar aún más la violencia. Sin embargo, el CJNG no es inmune a la presión. El descubrimiento de lugares de detención masiva en Jalisco41Mariana Fernández, “Killing Camp in Mexico Shows Horrors of CJNG Forced Recruitment,” Insight Crime, 25 de marzo de 2025 que se cree que pertenecen al CJNG, y el aumento del escrutinio por parte de las autoridades estadounidenses sugieren que su expansión puede enfrentarse a obstáculos cada vez mayores, dejando espacio para que actores criminales locales se impongan de forma más agresiva.

Mientras tanto, bajo la presión de la administración Trump, el gobierno mexicano parece estar respondiendo a la actividad criminal organizada y a la violencia en el país utilizando estrategias familiares estilo kingpin, que conllevan riesgos adicionales de fragmentar aún más el panorama criminal y crear vacíos de poder. En este contexto de volatilidad, la respuesta de seguridad ha pasado a formar parte de la dinámica cambiante, influyendo en las contiendas territoriales y en las alianzas emergentes. A lo largo de la frontera norte, una zona estratégica para las actividades de tráfico, ya existen indicios de que los grupos criminales locales pueden estar ganando en fuerza y autonomía. Es probable que las disputas criminales persistan hasta que surja una fuerza hegemónica.

Un posible escenario futuro implica mayores riesgos para la población civil, ya que la violencia amenaza con llegar a nuevas zonas. La intensificación del conflicto en Sinaloa ha expuesto a la población civil a una mayor violencia por alinearse con el grupo rival y a un aumento de los niveles de extorsión, ya que los grupos criminales buscan fuentes de ingresos para financiar su guerra. Si la violencia llegara a extenderse aún más, las perspectivas para los civiles serían sombrías. Del mismo modo, las figuras políticas son especialmente vulnerables a los cambios en los equilibrios de poder en sus localidades, ya que los grupos armados intentan consolidar su control territorial mediante la gobernanza criminal y para mitigar las operaciones de las fuerzas de seguridad contra sus intereses.

Más preocupante es la posibilidad de que la presión estadounidense sobre la evolución de la seguridad en México se extienda más allá de las amenazas de sanciones económicas. El embajador de EE.UU. en México no ha descartado la posibilidad de una intervención concertada o unilateral de EE.UU. en suelo mexicano en un momento en que aumentan los vuelos de drones de vigilancia en México.42Dan De Luce, Ken Dilanian, and Courtney Kube, “Trump administration weighs drone strikes on Mexican cartels,” NBC News, 8 April 2025 Tal escenario equivaldría a un retorno en toda regla a la estrategia kingpin, un enfoque que históricamente ha conducido a la escisión de los grupos criminales y a la intensificación de la violencia en territorios disputados y localizados, cuyas consecuencias pueden ir en contra de los objetivos declarados del gobierno mexicano.

Este informe fue elaborado en inglés y fue posteriormente traducido al español. En caso de discrepancias, los usuarios deben remitirse al informe en inglés.

Visuals produced by Ana Marco and Ciro Murillo.