Read our most recent analysis on the Philippines’s war on drugs and our monthly Regional Overviews for updates on violences in the Philippines.

President Rodrigo Duterte assumed office in the Philippines in June 2016 and shortly thereafter declared a ‘War on Drugs’. This ‘war’ refers to the drug policy of the Philippine government, aimed at “the neutralization of illegal drug personalities nationwide” (Rappler, 2017). The campaign has resulted in the deaths of thousands of Filipinos, largely the urban poor (Human Rights Watch, 2018). ACLED’s newly updated data allow several preliminary conclusions: first, anti-drug ‘vigilantes’, which perpetrate roughly half of the total drug violence reported, are likely supported by or under the control of Duterte’s regime, despite their unofficial status. Second, publicly available data represent only a small portion of the total extent of the war on drugs, which in turn indicate that the official death toll is likely a vast underestimate of the total human cost of this war. And finally, despite stopgap measures, Duterte’s focus on the War on Drugs has diverted meaningful attention from other political violence issues in the Philippines.

State links to violence

What has elicited international condemnation is the way in which violence in the Philippines has been supported by the government. The Philippine National Police (PNP) is responsible for many of the executions, and is accused of planting guns and evidence next to drug suspects they have executed (Human Rights Watch, 2018; Reuters, 2017). A report by Amnesty International highlighted the ‘economy of murder’ that has been established as a result of “cash reward[s] paid out for every dead body incentiviz[ing] police to kill individuals who were mostly poor and often defenseless” — with no payment given for arrests (Deutsche Welle, 2017).

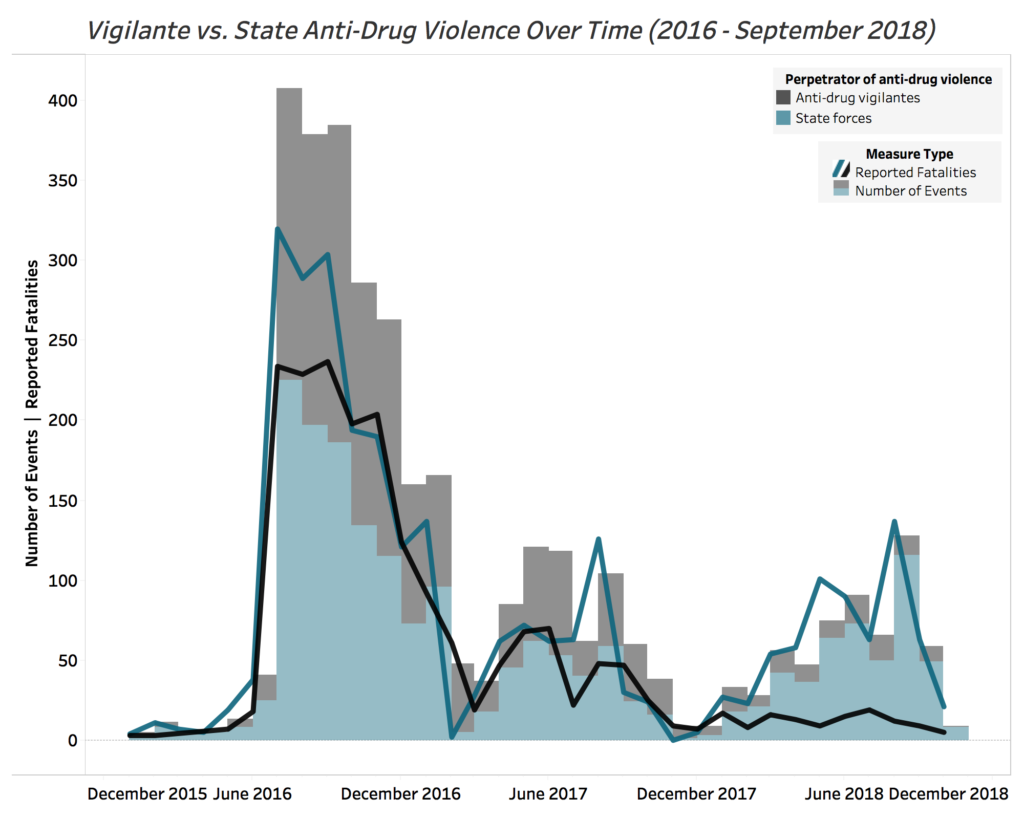

In addition to the PNP, Duterte has also urged people to seek out and kill suspected drug addicts (The Guardian, 2016). This has resulted in the targeting of suspects by anti-drug vigilantes, seemingly emboldened by the current climate. However, further damning are accusations that at least some of the extrajudicial killings carried out by vigilantes were outsourced to them by the police (Rappler, 2018), or may even be police in masks and/or are groups relying on police to secure the perimeter in the lead up to such attacks (Deutsche Welle, 2017). Such accusations are supported by the in-tandem rise and fall of violence perpetrated by the state and anti-drug vigilantes. The graph below shows nearly simultaneous cycles of drug violence perpetrated by state and non-state actors. Anti-drug vigilantes and state forces each perpetrate roughly equal shares of the violence, and the activity of each appears largely responsive to changes in government policy. This responsiveness indicates a level of government control over supposedly unofficial armed agents.

The people targeted are those who have been named suspects on the President’s ‘watch list’ — a list of “names of suspects from local police officers and elected officials … containing anywhere from 600,000 to more than a million suspects”; some three million Filipinos — 3 percent of the population — were named as ‘drug addicts’ and hence on the list to be targeted (New York Times, 2017). “Duterte made a point of naming names across a broad swath of Philippine society, including 6,000 police officers and 5,000 local village leaders he called corrupt. How they ended up on the list, or even who exactly was on it, was a mystery that fascinated Filipinos. How you got off the list was even more mysterious” (New York Times, 2017).

There are accusations that the government is using the War on Drugs to kill, detain, or threaten politicians. For example, twelve mayors have been killed since July 2016. Four of the victims were on the government’s list of ‘narco-politicians’ (Time, 2018). Another former congressman was killed for allegedly ‘coddling’ drug lords (ABS-CBN, 2018). As of July 2018, there are 96 ‘narco-politicians’ on the government’s list. It has yet to be conclusively proven that the government is using the list to justify the assassination of rival politicians. Still, the War on Drugs has been cited as the basis for the arrest of opposition politicians like Senator Leila De Lima who has been tagged as “the mother of all drug lords” (Philippine Daily Inquirer, 2016). Groups like Amnesty International have decried the criminal charges against De Lima as “politically motivated” (Amnesty International, 2018). Human Rights Watch argues that the War on Drugs has been used to intimidate “politicians, especially in the provinces, who are then forced to toe Duterte’s line” (Time, 2018), allowing the state to excuse the targeting and assassination of politicians and to ‘cleanse’ the security forces of the Philippines under the guise of an ongoing campaign endorsed and encouraged by the government.

Drug violence as a means of large-scale political violence is nothing new for Duterte. “Large-scale extrajudicial violence as a crime solution was a marker of Duterte’s 22-year tenure as mayor of Davao City and the cornerstone of his presidential campaign “(Human Rights Watch, 2018). Though the War on Drugs announced following his election is a marked difference from his prior campaign, taking such violence to a new scale. The drug suspects killed by police in the first month of the Drug War campaign (July 2016) alone were more than twice that killed in police operations in the six months prior to Duterte’s election (January to June 2016) (Al Jazeera, 2016). Since the start of his presidency, the deaths of civilians claimed to be drug suspects and/or criminals by police and vigilante groups have been historically unprecedented (Rappler, 2017). Even the vigilante or “death squad” killings during the 22 years of Duterte’s time as mayor of Davao City do not compare to the number of fatalities that have occurred during Duterte’s first two years as President (Reuters, 2016).

Data & Coverage

While there are many efforts to consolidate the data, the total number of drug-related killings still remains elusive. To date, the figure ranges from 4,000 to 20,000 (Human Rights Watch, 2018; The Guardian, 2018). Given the significant rise in drug-related violence in the Duterte administration, and the highly politicized nature of the drug-related violence in the Philippines, ACLED categorizes this as political violence and has begun recording this type of violence. This type of violence manifests in a number of ways. ACLED includes drug violence in the Philippines – the killing of drug suspects by both government security forces (police/military) and by “vigilantes”, as well as inter-gang related violence. For more on ACLED’s methodological decisions and the assumptions made in efforts to accurately capture the patterns and trends of this violence, especially given the nature of reporting and their suspected veracity, see ACLED’s methodology piece here.

The death toll of the War on Drugs is highly contested. On the one hand, the government has been accused of underestimating the number of fatalities. On the other hand, the media and other civil society groups have been charged by the government and its supporters of inflating the numbers to discredit President Duterte. For example, the PNP originally claimed that there have been around 4,251 fatalities since July 2016 (as of April 2018) (The Philippine Star, 2018)[1], while human rights groups and news organizations contest that more than 12,000 people have been killed (Human Rights Watch, 2018). Senator Antonio Trillanes even argued that there have been more than 20,000 deaths (Al Jazeera, 2018).

There is an incentive for both the administration and opposition politicians to evade the numbers. According to a June 2018 survey of 1,200 adults nationwide, 96% of Filipinos believe that it is important that drug suspects are captured alive (Social Weather Stations, 2018). Hence, support for the War on Drugs and, by extension, the Duterte administration may erode if the number of fatalities seems too high. The opposition therefore stands to gain from convincing the public that far too many people have been killed. The government is, however, more likely to politicize the data. The government has already shown that it is willing to mislead statistics. For example, the chairperson of the Dangerous Drug Board, the government agency responsible for combating illegal drugs, was forced to resign for stating that there were only 1.8 million drug addicts in the country instead of the 4 million figure declared by Duterte (The Philippine Star, 2017). An in-depth analysis of official source documents by the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) revealed that the government’s unitary report on the Drug War is “writ in riddles and feature[s] flawed and inflated numbers that are wildly different from what the primary drug-war data source, the PNP, had reported on the same dates or for the same covered periods” (PCIJ, 2017). Estimating the death toll is hence difficult because of the politicized nature of the War on Drugs and the likelihood that the government is underestimating the fatalities.

To increase coverage of this ‘war’, ACLED is identifying and integrating new sources of information to better capture this violence. As a first tranche, ACLED has expanded source coverage to include coverage of the Philippine Daily Inquirer Kill List, “regarded as one of the most accurate records of the killings of suspected drug dealers in police engagements and by vigilantes” (CNN, 2016)[2]. This ‘Kill List’ is “an attempt to document the names and other particulars of the casualties in the Duterte administration’s war on crime” (Philippine Daily Inquirer, 2016), which covers casualties between July 2016 and February 2017. Even with the inclusion of the ‘Kill List’, the fatality count still falls on the lower side of the spectrum at around 4,600 fatalities. This is significantly lower than the figures given by non-government and human rights organizations, and close to the low number of fatalities reported by the government. However, ACLED’s fatality count should not be taken as corroboration of the official death toll claimed by Philippine authorities. The sheer scale of the War on Drugs, compounded by the politicization of this violence, has made it difficult for reliable sources to report a majority of its component killings. ACLED’s fatality count likely represents only a fraction of an immense whole, indicating significant under-reporting by the Philippine government (Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, 2017), and because only a subsection of events are reported in the press. Even so, more than 95% of drug-related violence reported in the country has resulted in fatalities. ACLED will continue to take steps to identify and integrate additional information in order to increase coverage of this ‘war’.

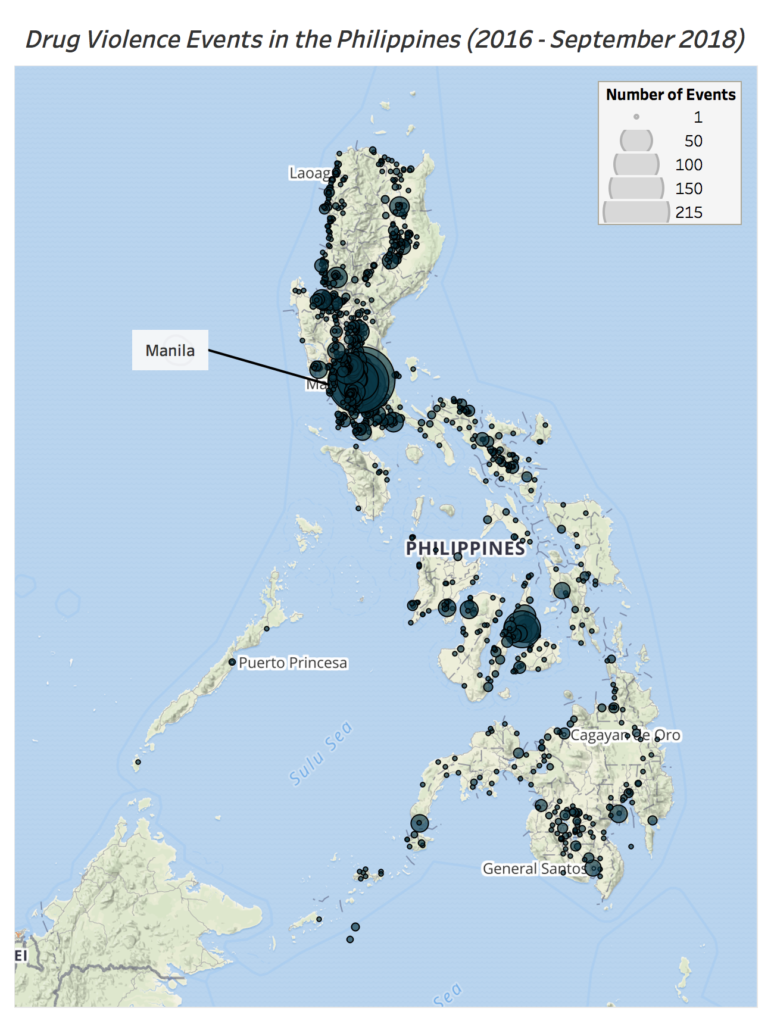

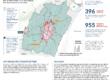

In addition to reporting difficulties given politicization, there are additional limitations as well, thwarting full coverage. For example, incidents in rural areas are likely underreported in the media (The Drug Archive, 2018). ACLED data on drug violence demonstrate that these events occur across the Philippines broadly, but particularly in urban regions, and particularly around Manila, the capital (see map below). It is likely that a large portion of drug violence events do indeed occur in urban areas. However, there may also be some underreporting in rural areas as media and civil society groups have less of a presence outside of urbanized areas, impacting the quality and quantity of coverage.

Timeline of Violence

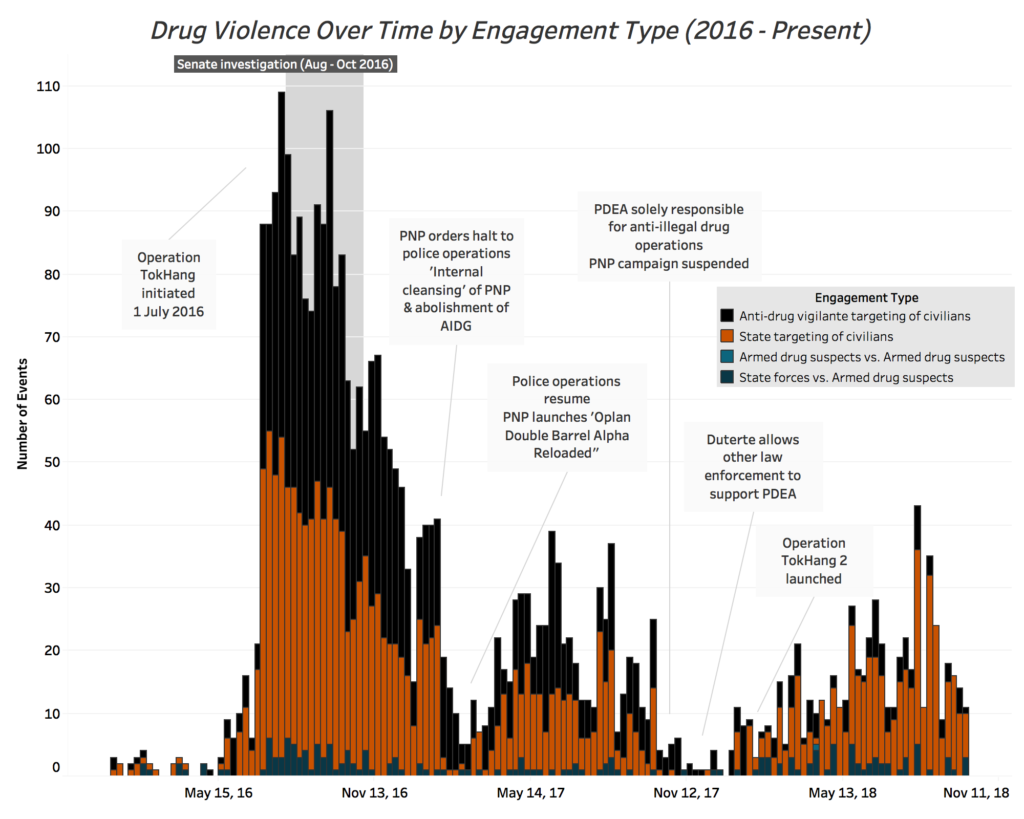

To better understand trends in the data, it is helpful to have a better understanding of the timeline of events shaping the Drug War — namely, state policies around the ‘war’, how they have shifted, and as a result how violence patterns too have shifted. The graph below depicts the temporal trends in the data, further discussed below.

On 1 July 2016, after the inauguration of Duterte as the newly elected President of the Philippines, the PNP issued Command Memorandum Circular No. 16 entitled, “PNP Anti-Illegal Drugs Campaign Plan – Project: Double Barrel” (PNP, 2016), detailing guidelines on police operations for the Drug War. The guidelines describe a two-pronged approach, namely, Project “TokHang” and “HVT.” TokHang, or “knock and plead,” comprises police house-to-house visitations encouraging anti-drug users and dealers to surrender and register on the drug watchlist, while HVT is the actual conducting of anti-drug operations by the Anti-Illegal Drugs Group (AIDG). Due to the massive participation of the community in its implementation, “Oplan TokHang” has been the more familiar term for the Philippine government’s response to the War on Drugs.

In the three weeks following the initial declaration of Oplan TokHang, the number of drug-related events skyrocketed to over 300, almost all of which targeted drug suspects. Nearly half of these events were perpetrated by anti-drug vigilantes, and half by the government.

In the course of the campaign, the implementation of the Drug War has been subjected to much scrutiny and multiple changes. One of the major investigations on state-sponsored killings occurred in the senate from August (CNN, 2016) to October 2016 (Rappler, 2016). Despite a relative decrease in events over the course of the senate investigation, it wasn’t until President Duterte ordered the PNP to cease its activities in early 2017 that the number of reported events and deaths substantially decreased to average less than 20, rather than 50 to 60, events per week. As the number of events decreased during this time, the ratio of perpetrators remained the same: about half of events targeting drug suspects were perpetrated by the state, and half by anti-drug vigilantes.

The first Presidential directive to discontinue ‘Project: Double Barrel’ occurred following the alleged abduction and murder of a South Korean by cops. The President, in a press briefing, announced an “internal cleansing” of the PNP and the abolishment of the AIDG. On 30 January 2017, the PNP ordered a halt to police anti-drug operations (Rappler, 2017). The number of events – both perpetrated by anti-drug vigilantes and by the state – dramatically fell following this announcement. The simultaneous fall in these agents’ activities indicates both the impressive level of control of the government over the War on Drugs as well as suggests coordination between state forces and unofficial agents.

On 27 February 2017, Duterte ordered the resumption of police operations but through smaller groups of task forces with no history of corruption[3]. The PNP officially re-launched and renamed its Drug War campaign, “Oplan Double Barrel Alpha Reloaded,” on 6 March 2017 (PNP, 2017). This is to be implemented by the Drug Enforcement Group (DEG), replacing the AIDG. In the weeks that follow, the number of events reported increases again, again fairly evenly divided between state and anti-drug vigilantes.

In the same year on 10 October 2017, Duterte issued yet another directive to all concerned agencies, assigning the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) as the sole agency responsible in anti-illegal drug operations (Official Gazette, 2017), indicating another suspension of the PNP campaign. Though nearly two months after this decision, Duterte again allowed the involvement of other law enforcement agencies to support the PDEA in the conduct of operations based on a memorandum dated 5 December 2017 (Official Gazette, 2017). As a result, between October and December of 2017, very few recorded events took place.

Meanwhile, Oplan TokHang, as part of the two phases of the Drug War campaign, had also undergone revisions. Oplan TokHang 2 was launched in 29 January 2018 (DILG, 2018). Even as the administration promises a less bloody and controversial Drug War campaign, the anti-drug operations and Oplan Tokhang 2 are still surrounded with questions as events still continue (Philippine Daily Inquirer, 2018), and the number of events reported have again begun to rise, reaching pre-October 2017 levels. While in many ways the events that comprise Oplan TokHang 2 look very similar to the events that comprised the first Oplan TokHang, one key difference emerges: instead of nearly half of events being perpetrated by the state and half by anti-drug vigilantes, an overwhelming majority of events during this time are reportedly being perpetrated by the state. This may be the result of the state’s effort to improve the campaign’s legitimacy, which in turn could indicate that the state exerts a high level of control over these unofficial vigilantes.

Other developments have followed. The data show a slight decrease in reported events in February 2018, during the time when the International Criminal Court (ICC) announced that it shall launch a preliminary examination into the killings to see if the Philippine government should be investigated for state crimes. The Philippines subsequently pulled out of the ICC in March (International Criminal Court, 2018). In addition, a slight dip in reported killings also occurred in April during the time when then PNP chief Director General Ronald dela Rosa, a trusted ally of Duterte, was replaced by a new PNP chief.

Conflict Landscape in the Philippines

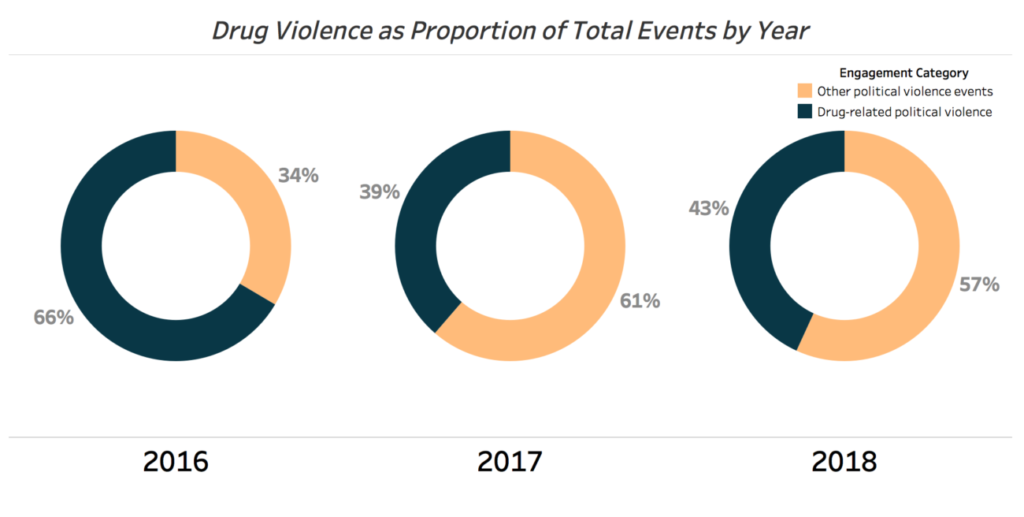

The conflict landscape in the Philippines since 2016 has been in some ways dominated by Duterte’s War on Drugs. Since 2016, over half of the political violence events in the Philippines have been the result of the War on Drugs – largely the targeting of alleged drug suspects by the state or by anti-drug vigilantes. Since soaring to encompass nearly 70% of the political violence landscape shortly after its inception in 2016, the number of events in the War on Drugs has declined slightly, yet still encompasses well over a third of the political violence activity in the Philippines (see figure below). All other categories of events – including a decades-old insurgency waged by Islamist and communist groups in the south, and kidnapping-for-ransom by fractured rebel groups and pirates – average a combined 100 events per month during the past two years.

Drug violence also diverts state resources from combatting other political violence in the Philippines. Because a large portion of non-drug-related violence in the Philippines consists of battles, in particular against the state, high levels of state engagement in the targeting of suspected drug users can limit its ability to engage with violent actors outside its purview. As such, since the start of the Drug War, the government of the Philippines has invested in political, rather than military, methods of addressing violence beyond the Drug War. For example, a deal in August 2018 which granted some autonomy to Muslim residents of Mindanao was partially directed towards the reduction of violence on the island (Voice of America, 2018). Duterte has also continued to extend martial law throughout the province, limiting access to arms and solidifying state control from afar.

While Duterte’s inappropriate comments regarding extrajudicial killings and violence — such as his confirmation of personally shooting dead three men while mayor of Davao (BBC, 2016), or his stating that “‘criminals don’t have any humanity’, so killing them is not a crime” (The Guardian, 2017), or referring to children killed during police operations as ‘collateral damage’ (Al Jazeera, 2018) — encourage killings, so do policy and budget appropriations. A number of various policies have shifted to support the Drug War: supplementation of the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA), providing additional forces from the Philippine National Police (PNP) to pursue its drug operations, the Philippines pulling out of the International Criminal Court (ICC), the increasing of police salary, etc. Yet the relationship between the War on Drugs and the larger conflict landscape in the Philippines is complex. Differences in geographic location serve to physically separate the majority of drug- and non-drug-related political violence in the Philippines; however, the state’s focus on the War on Drugs decreases state engagement in other conflicts across the Philippines, and further provides a convenient cover for its activities in others.

Electoral violence has long been a norm in Philippine elections. It is for this reason that “guns, goons, and gold” have been referred to as “the three Gs of old-school Filipino politics” (The Guardian, 2010). The War on Drugs, however, introduces a new dynamic to electoral violence in the Philippines. It is possible that the Drug War will be used by state agents to justify the arrest or killing of candidates. For example, earlier this month from October 7 to 13 (the final week for politicians to file their candidacy), there were at least 4 assassination attempts against potential candidates. Three attempts succeeded. As demonstrated in the case of Senator Leila De Lima, the government is not above using the issue of drugs to justify a crackdown on opposition politicians. It is not a stretch to predict that opposition candidates will be arrested and/or killed by state or vigilante actors as part of anti-drug operations in the lead up to the May 2019 elections.

As Duterte funnels state resources towards the War on Drugs, his administration has approached other political violence across the country with short-term policy shifts intended to avoid committing high concentrations of state resources. This trend will likely continue as the War on Drugs progresses. Martial law in Mindanao, for instance, has been extended twice, and though it is currently scheduled to end 31 December 2018, it is likely that Duterte will extend it yet again. The deaths of several outspoken critics of the law (Manila Bulletin, 2018) raise questions about the ways in which the law effectively caps violence, and reports of increased IED-use suggest rebel groups in the area will find ways around the martial law’s strict restrictions on firearms (ABS-CBN, 2018). Current policies aimed at reducing the need for government involvement beyond the War on Drugs are therefore not long-term solutions, and do not sufficiently alter conditions such that the state can expect the lower conflict levels to last (Rappler, 2018). Sooner or later, the state will have to meaningfully re-engage in Mindanao and elsewhere. Such a shift may increase the state’s reliance on unofficial ‘vigilantes’ to target drug suspects yet again, or may cause the state to double-down on rights-restricting policies in order to further decrease the scope for other types of violence in the Philippines.

Find an explanation of ACLED’s methodology for monitoring drug violence in the Philippines here.

[1] The PNP later ‘corrected’ their figure, though still claim it is fewer than 7,000 (Philippine Daily Inquirer, 2017).

[2] “Three individuals previously reported dead [on the PDI Kill List] have since been confirmed alive; [PDI] has removed them from the count but keeps their names on the list with the disclaimer that they are still alive” (Philippine Daily Inquirer, 2016; see also MindaNation, 2016). ACLED has accounted for such cases and will continue to make any necessary updates as new information comes to light.

[3] The Philippine Daily Inquirer Kill List ended its coverage of the killings in February 2017.