As Prime Minister Hun Sen consolidates his grip on power, Cambodia has seen a marked decline in demonstrations. With the opposition party dismantled and independent media shut down, Cambodia faces an increasingly authoritarian climate. While demonstrations have declined, land and labour issues — the source of many demonstrations — continue to drive political disorder in the country. While the crackdown on freedom of assembly has cost Cambodia in its relationships with Western countries, it has also facilitated closer relations with China, Cambodia’s largest foreign investor, whose foreign policy approach of non-interference overlooks the use of repression in states that receive aid and investment (Kishi & Raleigh, 2017). The incentive to maintain a secure environment to attract investment has likely led to both increased repression of demonstrations and also, notably, recent attempts to co-opt traditionally opposition-aligned garment workers through previously scorned economic populist policies (Asia Times, 22 January 2019).[1] However, the inability of employers to meet the demands of recently passed laws makes the possibility of increased demonstrations, followed by increased repression, increasingly likely.

Dismantling the Opposition

Seeking to avoid a repeat of 2013 — when the opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) challenged the dominance of Hun Sen’s Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) — in November 2017, the Cambodian Supreme Court dissolved the CNRP. Without any formidable opposition party to challenge the CPP, the general elections in July 2018, in which the CPP won all seats in parliament, were viewed as a sham (VOA Cambodia, 28 July 2018).

Despite trying to maintain unity, the ongoing repression of CNRP leaders has also resulted in party in-fighting, further weakening any challenge to Hun Sen’s power. With the current party leader, Kem Sokha, under house arrest and the former party leader, Sam Rainsy, in exile, the uneasy alliance between the two leaders has been tested by Sam Rainsy’s recent declaration of himself as leader while Kem Sokha remains under house arrest (The Diplomat, 12 December 2018). In an effort to reveal Hun Sen’s control of the Cambodian courts, Sam Rainsy set a 3 March 2019 deadline by which Hun Sen should release Kem Sokha and vowed to return to Cambodia to face outstanding charges should Hun Sen fail to release him (Radio Free Asia, 11 November 2018).

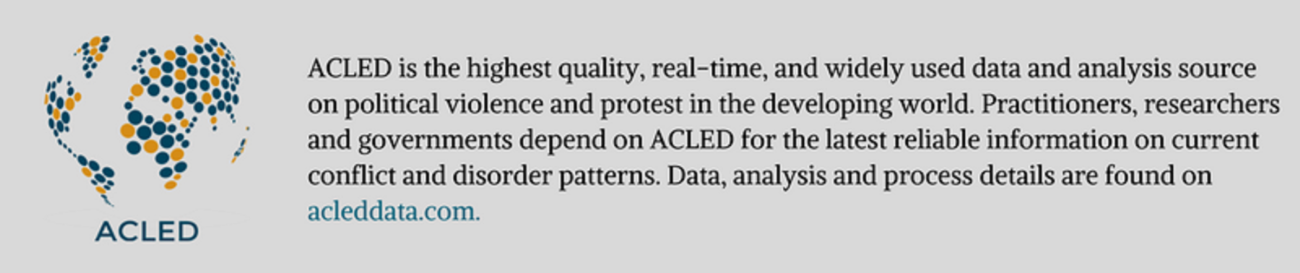

By moving to dismantle the opposition prior to elections, Hun Sen ensured his continued rule. Having stated that he was sorry he had not killed protesters, including Sam Rainsy, back in 2013 (Radio Free Asia, 29 November 2018), Hun Sen likewise had banned any protests outside parliament prior to the 2018 elections (VOA Cambodia, 03 May 2018). As such, while there were no reports of large-scale demonstrations taking place during the 2018 election period (see Figure 1), the CNRP did push for citizens to spoil their ballots as a sign of protest against the elections (Independent, 30 July 2018).

The decline in demonstrations beginning in 2017 and continuing into the present also reveals how land and labour issues drive political disorder in the country. The bond between the CNRP and trade unions has brought about repression of labour related demonstrations. As well, the CPP’s extensive involvement with various companies engaged in land disputes with villagers has fueled demonstrations over forced evictions.

Land Demonstrations

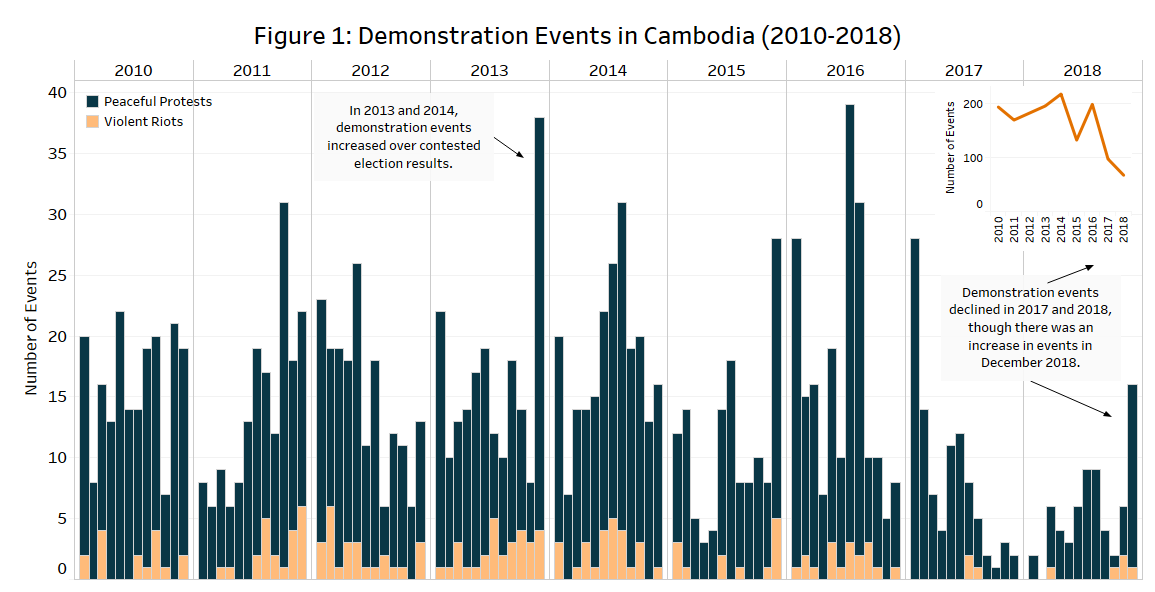

A significant cause of demonstrations in Cambodia are the numerous land disputes throughout the country. From 2010 to 2018, ACLED recorded 497 demonstration events concerning land-related issues (see Figure 2). With many in the country lacking land ownership documents — a result of the destruction of the Khmer Rouge period — the CPP has taken advantage of this through a 2001 Land Law that allows for Economic Land Concessions (ELC) in which the government can lease land to companies for up to 99 years (The New York Times, 18 July 2012). Without documents to disprove the government’s claim to the land, many villagers are forcibly evicted, resulting in many demonstrations.

Most notably, the residents of the Boeung Kak lake area in Phnom Penh have engaged in sustained demonstrations over the years against their eviction to make way for a company with links to a CPP senator. Among the demonstrators, Tep Vanny, has led a group of women against the confiscation of their lands (Front Line Defenders, 23 August 2018). These demonstrations reveal the extent to which members of the CPP have aligned themselves with various companies to profit off of such land grabs. Land grabs are often for the purpose of development projects, or to clear land for sugar or rubber plantations.

Demonstrations over land disputes frequently become violent when state forces attempt to carry out forced evictions. In March 2018, state forces shot those resisting the demolition of their houses to make way for a rubber plantation in Kratie province (Radio Free Asia, 8 March 2018). Early in 2019, in Preah Sihanouk, state forces likewise shot at protesters demonstrating over contested land. Government-approved Chinese investment in Sihanoukville, part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, and the resulting land conflicts have led to many demonstrations in recent years (The Phnom Penh Post, 8 December 2017). With a number of special economic zones such as Sihanoukville designated across the country, foreign investment and the land disputes that follow are likely to continue.

Labour Demonstrations

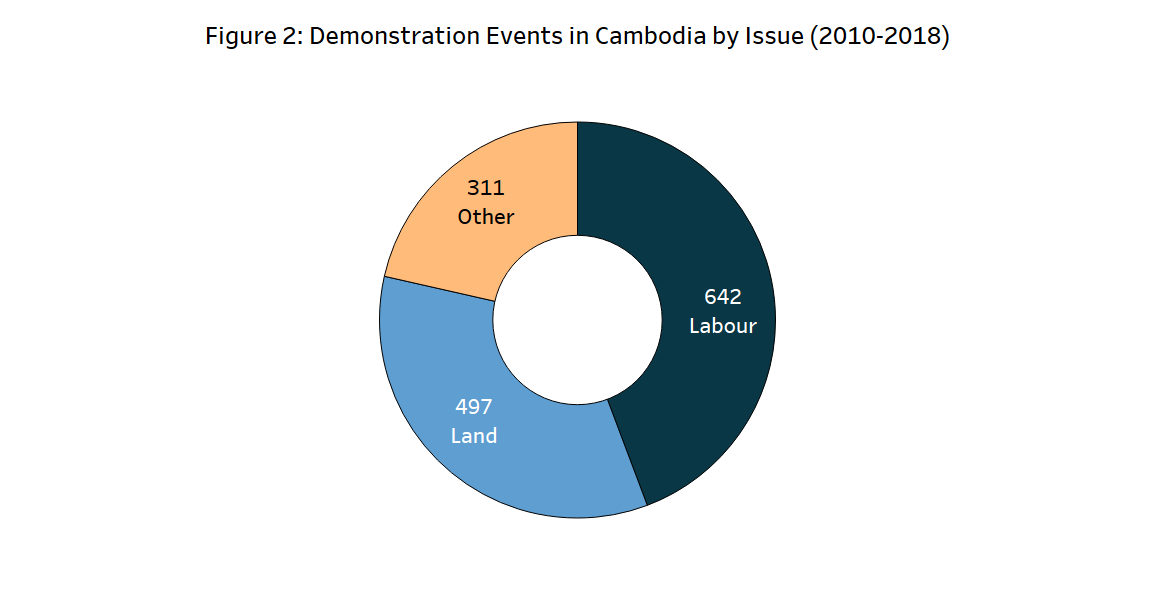

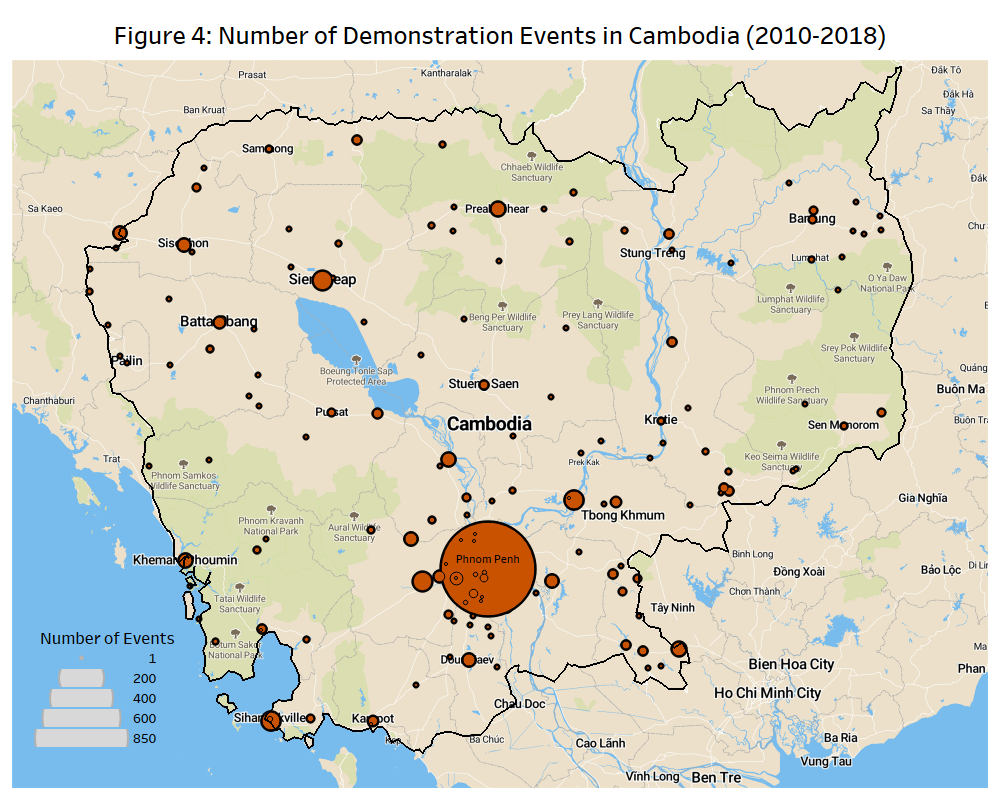

Aside from demonstrations over land disputes, labour demonstrations comprise a significant proportion of the demonstrations in Cambodia. Between 2010 and 2018, ACLED recorded 642 labour demonstration events (see Figure 2). Of these labour demonstrations, 59% of them are demonstrations by garment workers (see Figure 3). Most labour and land demonstrations take place in the capital, Phnom Penh, with many often traveling to the capital to voice their grievances (see Figure 4).

The alignment of the trade union movement with the CNRP has often led to crackdowns on organizing by garment workers (Asia Times, 2 May 2018). From 2010 until 2015, workers staged several massive coordinated protests calling for an increase of the minimum wage and better working conditions. However, in recent years, there has been a considerable drop in reports of trade union registrations as well as protests and strikes. The Garment Manufacturers Association of Cambodia (GMAC), an employers’ association, attributes the reduction in strikes and protests to “continuously improving conditions, especially in the area of wages, compensation and social security coverage” (Equal Times, 3 December 2018). In contrast, unions and activists see the reason for the decline in the government’s warnings, threats, and intimidation (Equal Times, 3 December 2018) — which increased significantly after major demonstrations in December 2013 and January 2014.

The opposition CNRP has explicitly supported workers’ demonstrations and campaigned for a higher minimum wage (Radio Free Asia, 24 December 2013). The 2013 anti-government protests organized by the CNRP in Phnom Penh were joined by many workers and paralyzed the entire Cambodian industrial system. On 3 Jan 2014, police forces violently suppressed the protests by opening fire on the striking workers. Four protesters were killed and over 20 were injured in the crackdown. The mobilization of workers by the CNRP and the “possible fusion of the two protest movements [the anti-government demonstrations alongside the workers’ demonstrations] is commonly seen as the ultimate reason behind the violent crackdown of the strike” (Salmivaara, 2 November 2017).

In the aftermath of the 2013-2014 protests, the Cambodian government responded harshly towards union activities by raising criminal charges against protest leaders and sharply limiting the registrations of unions (Human Rights Watch, 29 April 2014). In April 2016, the National Assembly passed a contentious trade union law. The CNRP voted against the law, a move widely criticized by trade unions and international labour rights groups. The critics held that the increased criteria for union organization and registration, as well as for strikes, limited freedom of association and thus violated international standards as well as Cambodia’s constitution (Asian Correspondent, 14 April 2016). A protest against this legislation in front of the National Assembly was violently dispersed by security guards, injuring a unionist and a labour leader (The Cambodia Daily, 5 April 2016).

Besides the violent government backlash, employees occasionally face violent clashes with pro-government groups or security forces. For instance, in February 2016, about 50 former drivers of the Capitol Bus Company, who were protesting against their dismissal based on trade union activities, were violently attacked by members of the Cambodia for Confederation Development Association, which “is widely perceived as acting at the behest of employers” (The Phnom Penh Post, 8 February 2016). Two of the protesters were arrested and four trade union leaders were later charged with incitement (The Phnom Penh Post, 10 February 2016). A similar incident was reported recently in Phnom Penh on 18 December 2018 when more than 500 protesting garment workers from City Spark Cambodian Co Ltd were attacked by ten unidentified assailants with sticks and hoes. The crudely armed rioters were allegedly hired by the company to break up the protest.

With the CNRP sidelined, more recently, Hun Sen and the CPP have adopted CNRP economic populist policies to win over garment workers traditionally aligned with the opposition. However, such efforts may lead to greater unrest when factories are unable to meet the law’s requirements (Asia Times, 22 January 2019). Since mid-December 2018, a slight increase in labour protests can be observed stemming from recent amendments to the labour law stipulating indemnity payments are made every six months. In particular, garment workers have been staging demonstrations demanding seniority indemnity, severance benefits, and wage increases. From December 2018 continuing into January 2019, for example, workers from W&D Cambodia Co Ltd went on strike to demand payment of seniority indemnity in one lump sum before the implementation of the new law.

Conclusion

With the European Commission currently considering ending its Everything But Arms (EBA) preferential trade agreement with Cambodia in response to the growing authoritarianism, Cambodian workers are likely to face increased job loss should factories start to leave the country (Southeast Asia Globe, 5 February 2019). As Hun Sen has indicated (VOA Cambodia, 20 February 2019), it is likely that any subsequent demonstrations by dissatisfied garment workers will be met with force as the loss of European investment would compel Cambodia to move even closer to China, and thus attempt to secure the environment for investment. As well, Hun Sen’s grip on power seems unlikely to end soon given his family’s control of the economy and use of policies that deprive people of their land (Global Witness, 7 July 2016). While the recent lull in demonstration activity is notable, it is possible that simmering tensions over land and labour disputes will lead to increased disorder in the future.

Notes:

[1] For more on the link between foreign investment and conflict, see Kishi, R., Maggio, G. & Raleigh, C. (2017). Foreign Investment and State Conflicts in Africa. Peace Economics, Peace Science and Public Policy, 23(3), pp. -. Retrieved 22 Feb. 2019, from doi:10.1515/peps-2017-0007