Conflict Watchlist 2025 | Sudan

Foreign meddling and fragmentation fuel the war in Sudan

Posted: 12 December 2024

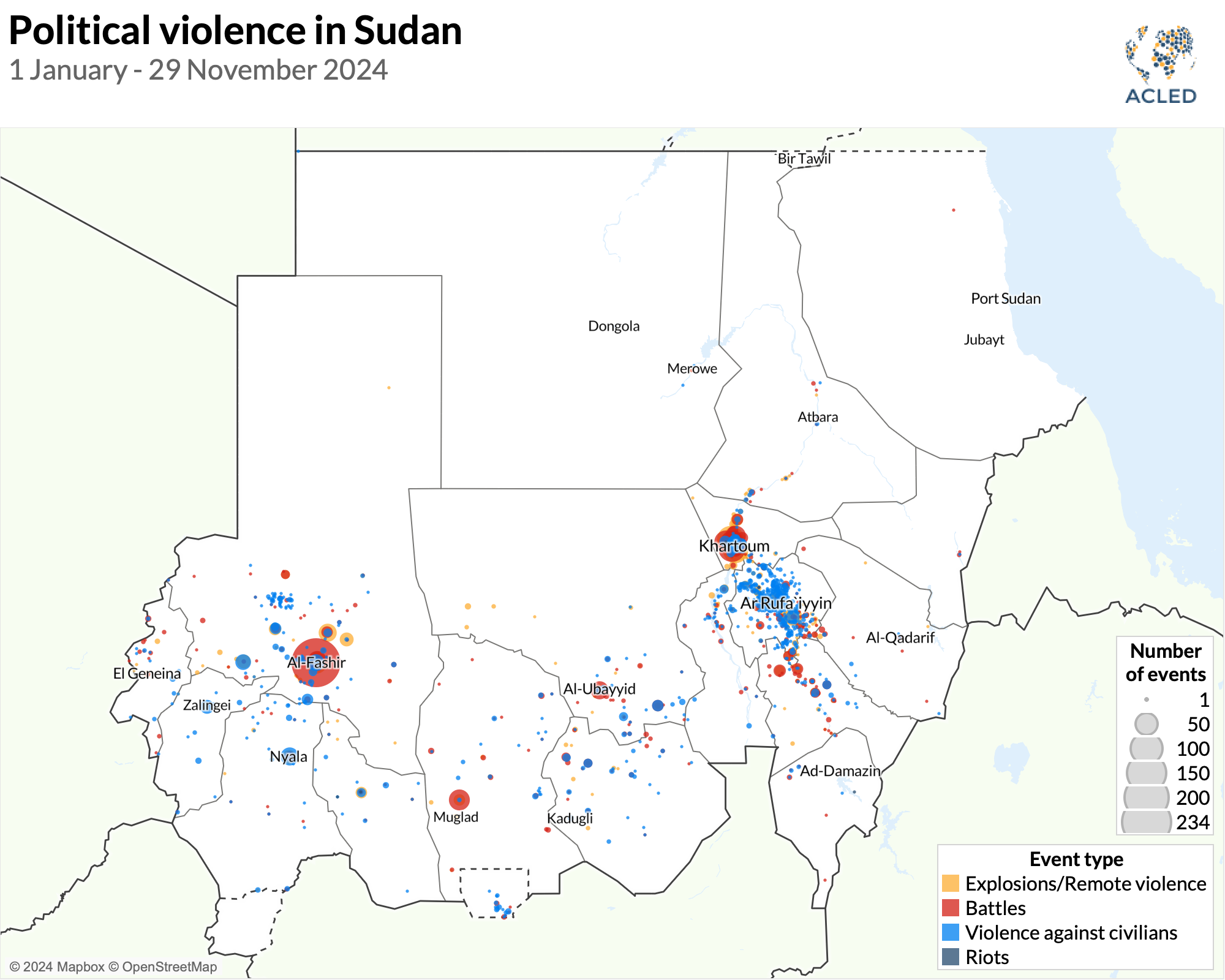

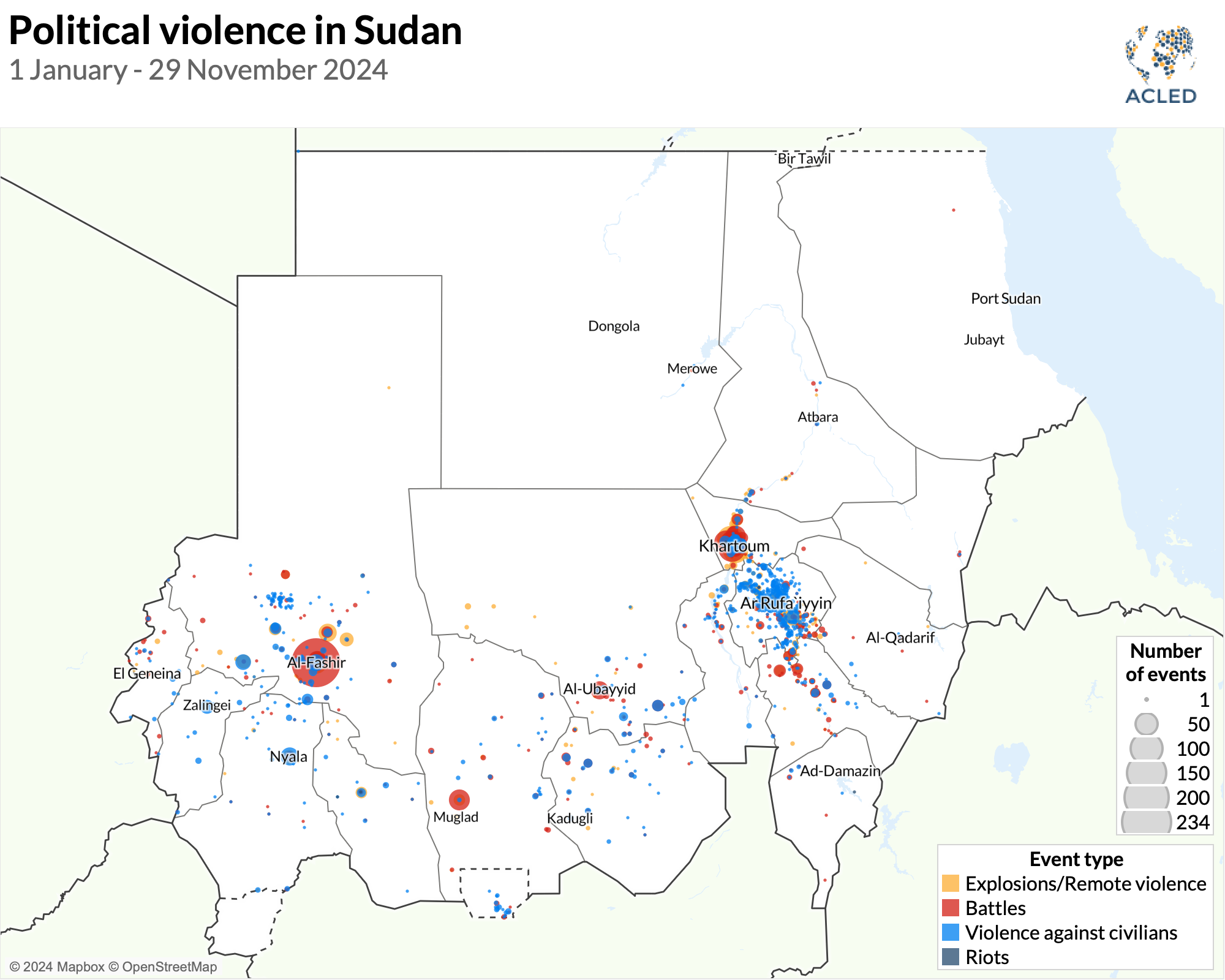

Twenty months of war have wreaked massive destruction in Sudan. ACLED records over 28,700 reported fatalities by the end of November 2024, including over 7,500 civilians killed in direct attacks. These numbers are assumed to be an underestimate of the war’s actual death toll, which some have put as high as 150,000.1Kalkidan Yibeltal and Basillioh Rukanga, ‘Sudan death toll far higher than previously reported – study,’ BBC, 14 November 2024 This conflict has left over half of Sudan’s population in need of humanitarian aid, and over 30% of the population has been displaced.2Associated Press, ‘War in Sudan has displaced over 14 million, or about 30% of the population, UN says,’ 29 October 2024 Thus, Sudan ranks as the fourth-deadliest conflict in the world, according to the ACLED Conflict Index.

The conflict between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), born out of a struggle for power between General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and Mohamed Hamdan ‘Hemedti’ Dagalo, has precipitated a nationwide war. While much of the fighting has continued to ravage Sudan’s symbolic heart, Khartoum, in 2024 the conflict increasingly shifted toward neighboring al-Jazirah state — strategically important for its main roads linking several states — and the Darfur region, the RSF’s traditional base. Since September, the SAF has launched offensive operations to oust RSF troops from Khartoum, Sennar, and al-Jazirah states, coordinating their forces to besiege RSF positions. The SAF scored several successes, recapturing Sennar state’s capital, Sinja, and lifting a long-running siege on two military bases in Bahri, Khartoum. In Darfur, for its part, the RSF and its allied Arab militias continue to besiege the North Darfur state capital of El Fasher, the only Darfurian capital that has not fallen to the RSF. In September, the Darfur Joint Forces, an SAF-allied resistance force, opened a new front in North Darfur to stretch the RSF’s military and logistical capacity.

Beyond the fighting between the RSF and SAF, other groups — such as ethnic militias and alliances — have emerged as key parties to the conflict. These ethnic militias and armed groups joined the conflict to protect local communities from the violence engulfing Sudan, as the SAF proved unable to resist RSF advances. The Darfur Joint Forces, initially established as a collective neutral force, is the third-most active group in the conflict after the RSF and SAF. It was first deployed on 27 April 2023 to protect civilians in El Fasher, one week after the conflict erupted in Khartoum. However, since March 2024, various members of the Darfur Joint Forces have changed their neutral stance, with some backing the SAF, while others maintained their neutrality.

The RSF also seems to be suffering from internal disputes among its ranks. In August and September 2024, there were a high number of clashes among members of the RSF. Most notably, after the defection of senior RSF commander Abu Aqla Keikel in October 2024, the RSF sought revenge by targeting the population of al-Jazirah, and particularly Keikel’s ethnic group, the Shukriya. The retaliatory attack against the Shukriya in al-Jazirah killed hundreds of civilians and forced thousands to flee their homes, in one of the worst atrocities against civilians this year. These developments appear to show cracks in the RSF’s strategy of maintaining unity.

The threat from the sky, in the form of air and drone strikes, became a prominent feature of the conflict in 2024. The SAF has maintained aerial supremacy throughout the conflict, with its air force striking RSF positions across the country. In 2024, however, the RSF ramped up its use of combat drones, reaching well beyond active frontlines. Among these attacks was a drone strike that targeted a military parade attended by SAF Commander Burhan on 31 July in Red Sea state. There is evidence that the United Arab Emirates has supplied lethal weapons to the RSF — though it has officially denied such involvement — while Eritrea, Egypt, Russia, and Iran have provided military aid to the SAF.3Aidan Lewis, ‘Sudan’s conflict: Who is backing the rival commanders?,’ Reuters, 12 April 2024; Khalid Abdelaziz, Parisa Hafezi and Aidan Lewis, ‘Sudan civil war: are Iranian drones helping the army gain ground?,’ Reuters, 10 April 2024; Voice of America, ‘SAF, RSF Conflict Threatens Sudan’s Eastern Border,’ 1 February 2024; Sudan Tribune, ‘Russia offers ‘uncapped’ military aid to Sudan,’ 30 April 2024; Andrew McGregor, ‘Russia Switches Sides in Sudan War,’ Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 21 Issue: 102, The Jamestown Foundation, 8 July 2024; United Nations Security Council, ‘Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan,’ 15 January 2024; Middle East Monitor, ‘Khartoum again accuses UAE of supporting Rapid Support Forces,’ 15 October 2024 Foreign meddling has consequently contributed to conflict escalation. ACLED records an increase in SAF drone strikes following reports that Iran provided the SAF drones at the end of 2023.4Khalid Abdelaziz, Parisa Hafezi and Aidan Lewis, ‘Sudan civil war: are Iranian drones helping the army gain ground?,’ Reuters, 10 April 2024 Likewise, the number of SAF airstrikes against the RSF in Darfur increased in August 2024 after the SAF received 15 new fighter jets supplied by Russia and Egypt.

What to watch for in 2025

The war in Sudan is at a crossroads. Although the SAF has arguably gained momentum in Khartoum, Sennar, and al-Jazirah states, prospects for peace are slim. Peace initiatives undertaken by the United States, Saudi Arabia, and the African Union have thus far achieved no meaningful outcome. Burhan puts the withdrawal of the RSF from all territories it controls as a precondition for coming back to the negotiation table, pointing to the Declaration of Principles for the Protection of Civilians that was signed in May 2023.5Sudan War Monitor, ‘Al-Burhan rejects talks with RSF in blow to peace efforts,’ 20 November 2024; Sudan Tribune, ‘Sudanese army’s return to negotiations hinges on RSF withdrawal from Khartoum: statement,’ 29 July 2023 Foreign meddling and constant arms transfers, in turn, fuel both parties’ belief that they could win the war.6Sudan Tribune, ‘Sudan’s Burhan vows victory as army advances in Khartoum Bahri,’ 28 September 2024 The SAF will continue its offensive campaigns in Khartoum, Sennar, and al-Jazirah to break the remaining RSF positions. In the west of the country, the RSF will likely push on El Fasher to seize full control of Darfur and remove other groups from the region.

However, with the war dragging on indefinitely, the risk of an increasingly fragmented conflict environment in 2025 increases. Several armed groups, often seeking foreign backing, are positioning themselves to fill power vacuums across the country and establish themselves as security providers. Popular Resistance Forces — armed militias consisting of civilians in arms — have emerged in several regions with support from the SAF, opening the door for the proliferation of armed groups and small arms.7Radio Tamazuj, ‘Q&A: Popular Resistance group seeks unity of resistance in Sudan,’ 18 April 2024 Eritrea instead opened its borders and established training camps for SAF-allied forces in the east, bolstering its influence along the Red Sea coast.8Dabanga, ‘Eritrea military training camps raise concerns about security in eastern Sudan,’ 24 January 2024 These moves have raised fears that ethnic conflicts in the region may reignite.

The RSF’s decentralized and horizontally organized structure, which builds on existing communal social networks, could also lead to fragmentation and exacerbate violence. Its networked structure does not always guarantee a coherent chain of command, as the level of coordination between mid-level ethnic militia commanders is low. Local agendas and ethnic affiliations often collide with the RSF’s national goals, with alliances frequently driven by pragmatic local power politics and security interests. Moreover, the RSF’s governance in areas under its control is inconsistent and often lacks functional institutions.9Interviews conducted by ACLED between October 2023 and October 2024; Tahany Maalla, ‘Beyond the Battlefield: The Survival Politics of the RSF Militia in Sudan,’ African Arguments, 14 October 2024; Sudan War Monitor, ‘RSF establish civil administration in West Kordofan,’ 17 September 2024; Radio Tamazuj, ‘Workshop ratifies formation of civil administration in RSF-controlled East Darfur,’ 6 June 2024; Hassan Alnaser, Mashair Idris, Mohamed Alagra and Omar al-Faroug, ‘SAF advances in North, West Darfur | Hilal rejects RSF attempt to impose civil administration in Fur territories | Cholera, dengue continue to spread,’ Mada, 19 October 2024; Darfur24, ‘RSF Civil Administration in South Darfur Claims Security is Maintained,’ 14 September 2024 This absence of effective governance structures could lead to instability and a power vacuum that could be exploited by ambitious RSF commanders and allied militia leaders, many of whom are motivated by direct economic gains — the RSF controls the Jebel Amer gold mines in Darfur and smuggles the gold to the UAE to be sold to the world market.10Africa Defense Forum, ‘Smuggled Gold Fuels War in Sudan, U.N. Says,’ 13 February 2024

The involvement of Islamist Omar al-Bashir loyalists who reject the idea of secular government and control key positions in the SAF11Sudan War Monitor, ‘Sudan reinstates sweeping powers for intelligence service,’ 15 May 2024; Khalid Abdelaziz, ‘Exclusive: Islamists wield hidden hand in Sudan conflict, military sources say,’ 28 July 2023 also plays a great role in the conflict and drives foreign countries’ support to the armed factions. This situation has prompted the UAE to back the RSF as a means to counter the Islamist agenda in Sudan. The UAE’s fight against Islamist groups extends to the Horn of Africa and the Libya-Sahel regions: It supports non-state armed forces or states combating Islamist groups like al-Shabaab and the Islamic State by increasing their military capacity or providing training and weapons.12Eleonora Ardemagni, ‘The UAE’s Rising Military Role in Africa: Defending Interests, Advancing Influence,’ Italian Institute for International Political Studies (ISPI), 6 May 2024 In Sudan, the UAE, which supports the RSF, is reportedly the most heavily invested foreign player in the conflict.13Yasir Zaidan, ‘To End Sudan’s War, Pressure the UAE,’ Foreign Policy, 29 August 2024; Husam Mahjoub, ‘It’s an open secret: the UAE is fuelling Sudan’s war – and there’ll be no peace until we call it out,’ The Guardian, 24 May 2024 Besides countering the Islamist movement, the RSF serves the UAE’s interests by supplying combatants for battles against the Houthis in Yemen and aiding Libyan National Army General Khalifa Haftar in Libya, thereby allowing the RSF to expand its operations along the borders with Libya and the Central African Republic.14Mohamed Mostafa, ‘Is the UAE fanning the flames of Sudan’s war?,’ The New Arab, 13 August 2024 Thus, the UAE’s assistance to the RSF aims to shape Sudan’s political landscape and influence the broader region to curb Islamist movements and protect the UAE’s agricultural products in Sudan to address its food security. The UAE wants to link its farm investments in Sudan with its Abu Amama port on the Red Sea, where it has so far invested over 6 billion US dollars.15Alma Selvaggia Rinaldi, ‘How Sudan’s RSF became a key ally for the UAE’s logistical and corporate interests,’ Middle East Eye, 1 September 2024 Many experts agree that the UAE’s continued support of the RSF is sustaining the conflict.16Middle East Eye, ‘A network of munition supply lines, backing the Rapid Support Forces against the Sudanese army, can be traced to the Gulf via Libya, Chad, Uganda and elsewhere,’ 25 January 2024 This unwavering backing will likely prolong the conflict, adversely impacting peace negotiations.

التدخل الأجنبي والانقسام يؤججان الحرب في السودان

خلفت عشرون شهرًا من الحرب دمارًا هائلاً في السودان. وسجّل مشروع (ACLED) أكثر من 28700 حالة وفاة حتى نهاية نوفمبر/تشرين الثاني 2024، بما في ذلك أكثر من 7500 مدني قُتلوا في هجمات مباشرة. ويُفترض أن تكون هذه الأرقام أقل من العدد الفعلي للقتلى في الحرب، والذي قد يصل إلى 150 ألف قتيل.[1] لقد أدى هذا الصراع إلى جعل أكثر من نصف سكان السودان بحاجة إلى مساعدات إنسانية، كما أدى إلى نزوح أكثر من 30% من السكان.[2] ويحتل السودان المرتبة الرابعة من حيث الصراعات الأكثر دموية في العالم، وفقًا لمؤشر مشروع (ACLED) للصراعات.

أدى الصراع بين القوات المسلحة السودانية (SAF) وقوات الدعم السريع (RSF) شبه العسكرية، والذي نشأ عن صراع على السلطة بين الجنرال/ عبد الفتاح البرهان ومحمد حمدان “حميدتي”، إلى اندلاع حرب على مستوى البلاد. وفي حين أن قدر كبير من القتال استمر في تدمير الخرطوم قلب السودان الرمزي، فمن المتوقع في عام 2024 أن يتحول الصراع بشكل متزايد نحو ولاية الجزيرة المجاورة – ذات الأهمية الاستراتيجية لطرقها الرئيسية التي تربط بين عدة ولايات – ومنطقة دارفور، القاعدة التقليدية لقوات الدعم السريع. ومنذ سبتمبر/أيلول الماضي، شنت القوات المسلحة السودانية عمليات هجومية لطرد قوات الدعم السريع من ولايات الخرطوم، وسنار والجزيرة، ونسقت قواتها لمحاصرة مواقع قوات الدعم السريع. وحققت القوات المسلحة السودانية عدة نجاحات، إذ استعادت مدينة سنجة، عاصمة ولاية سنار، ورفعت حصارًا طويلاً عن قاعدتين عسكريتين في بحري بالخرطوم. وفي دارفور، تواصل قوات الدعم السريع والميليشيات العربية المتحالفة معها محاصرة مدينة الفاشر، عاصمة ولاية شمال دارفور، وهي المدينة الدارفورية الرئيسية الوحيدة التي لم تسقط في أيدي قوات الدعم السريع. وفي سبتمبر/أيلول، فتحت قوة الحماية المشتركة في دارفور، وهي قوة مقاومة متحالفة مع القوات المسلحة السودانية، جبهة جديدة في شمال دارفور لتعزيز القدرات العسكرية واللوجستية في مواجهة قوات الدعم السريع.

وإلى جانب القتال بين قوات الدعم السريع والقوات المسلحة السودانية، برزت مجموعات أخرى ـ مثل الميليشيات العرقية والتحالفات ـ كأطراف رئيسية في الصراع. وانضمت هذه الميليشيات العرقية والجماعات المسلحة إلى الصراع لحماية المجتمعات المحلية من العنف الذي يجتاح السودان، حيث ثبت أن القوات المسلحة السودانية غير قادرة على مقاومة تقدم قوات الدعم السريع. إن قوة الحماية المشتركة في دارفور، التي أنشئت في البداية كقوة محايدة جماعية، هي ثالث أكثر القوات نشاطًا في الصراع بعد قوات الدعم السريع والقوات المسلحة السودانية. وقد تم نشرها لأول مرة في 27 أبريل/نيسان 2023 لحماية المدنيين في الفاشر، بعد أسبوع واحد من اندلاع الصراع في الخرطوم. ومع ذلك، فمنذ مارس/آذار 2024، غيّر العديد من الأعضاء بقوة الحماية المشتركة في دارفور موقفهم المحايد، حيث دعم البعض القوات المسلحة السودانية، بينما حافظ آخرون على حيادهم.

ويبدو أن قوات الدعم السريع تعاني أيضًا من خلافات داخلية بين صفوفها. ففي شهري أغسطس/آب وسبتمبر/أيلول 2024، وقع عدد كبير من الاشتباكات بين أفراد قوات الدعم السريع. ومن الجدير بالذكر أنه بعد انشقاق القائد الكبير لقوات الدعم السريع أبو عقلة كعكل في أكتوبر/تشرين الأول 2024، سعت قوات الدعم السريع إلى الانتقام من خلال استهداف سكان الجزيرة، وخاصة مجموعة الشكرية العرقية التي ينتمي إليها كعكل. وأدى الهجوم الانتقامي على مجموعة الشكرية في الجزيرة إلى مقتل مئات المدنيين وإجبار الآلاف على الفرار من منازلهم، في واحدة من أسوأ الفظائع ضد المدنيين هذا العام. ويبدو أن تلك التطورات تكشف عن وجود ثغرات في استراتيجية قوات الدعم السريع الرامية إلى الحفاظ على الوحدة.

وأصبح التهديد القادم من السماء، في شكل الضربات الجوية والطائرات بدون طيار، سمة بارزة للصراع في عام 2024. فقد حافظت القوات المسلحة السودانية على التفوق الجوي طوال الصراع، حيث قامت قواتها الجوية بضرب مواقع قوات الدعم السريع في جميع أنحاء البلاد. لكن في عام 2024، كثفت قوات الدعم السريع استخدامها للطائرات المقاتلة بدون طيار، لتصل إلى ما هو أبعد من الخطوط الأمامية النشطة. ومن بين تلك الهجمات غارة جوية بطائرة بدون طيار استهدفت عرضًا عسكريًا حضره قائد القوات المسلحة السودانية البرهان في 31 يوليو/تمّوز بولاية البحر الأحمر. وهناك أدلة على أن الإمارات العربية المتحدة زودت قوات الدعم السريع بأسلحة فتاكة – على الرغم من أنها نفت رسميًا تورطها في مثل هذا الأمر – في حين قدمت إريتريا ومصر وروسيا وإيران مساعدات عسكرية للقوات المسلحة السودانية.[3] وقد ساهم التدخل الأجنبي في تصعيد الصراع. وقد سجل مشروع (ACLED) في الشرق الأوسط زيادة في الغارات الجوية بطائرات بدون طيار تابعة للقوات المسلحة السودانية بعد تقارير تفيد بأن إيران زودت القوات المسلحة السودانية بطائرات بدون طيار في نهاية عام 2023.[4] وعلى نحو مماثل، ارتفع عدد الغارات الجوية التي شنتها القوات المسلحة السودانية ضد قوات الدعم السريع في دارفور في أغسطس/آب 2024 بعد أن حصلت القوات المسلحة السودانية على 15 طائرة مقاتلة جديدة قدمتها لها روسيا ومصر.

ما الذي يجب أن نراقبه في عام 2025

الحرب في السودان عند مفترق طرق. بالرغم من أن القوات المسلحة السودانية اكتسبت زخمًا في ولايات الخرطوم وسنار والجزيرة، فإن احتمالات السلام لاتزال ضئيلة. ولم تحقق مبادرات السلام التي تبنتها الولايات المتحدة والمملكة العربية السعودية والاتحاد الأفريقي أي نتيجة ذات معنى حتى الآن. ويضع البرهان انسحاب قوات الدعم السريع من جميع المناطق التي تسيطر عليها كشرط للعودة إلى طاولة المفاوضات، مشيرا إلى إعلان المبادئ لحماية المدنيين الذي تم توقيعه في مايو/أيار 2023.[5] ومن ناحية أخرى، فإن التدخل الأجنبي ونقل الأسلحة المستمر يؤديان إلى تأجيج اعتقاد الطرفين بأنهما قادران على الفوز في الحرب.[6] وستواصل القوات المسلحة السودانية حملاتها الهجومية في الخرطوم وسنار والجزيرة لكسر ما تبقى من مواقع قوات الدعم السريع. وفي غرب البلاد، من المرجح أن تضغط قوات الدعم السريع على الفاشر للسيطرة الكاملة على دارفور وإبعاد المجموعات الأخرى من المنطقة.

ومع ذلك، ومع استمرار الحرب إلى أجل غير مسمى، فإن الخطر يتزايد بنشوء بيئة صراع مجزأة بشكل أكثر في عام 2025. وتعمل العديد من الجماعات المسلحة، التي تسعى في كثير من الأحيان إلى الحصول على دعم أجنبي، على تهيئة نفسها لملء الفراغات في السلطة في جميع أنحاء البلاد وتأسيس نفسها كجهات راعية للأمن. وقد ظهرت قوات المقاومة الشعبية – وهي ميليشيات مسلحة مكونة من مدنيين مسلحين – في عدة مناطق بدعم من القوات المسلحة السودانية، مما فتح الباب أمام انتشار الجماعات المسلحة والأسلحة الصغيرة.[7] وبدلاً من ذلك، فتحت إريتريا حدودها وأنشأت معسكرات تدريب للقوات المتحالفة مع القوات المسلحة السودانية في الشرق، مما يعزز نفوذها على طول ساحل البحر الأحمر.[8] وأثارت تلك التحركات مخاوف من احتمال اشتعال الصراعات العرقية في المنطقة من جديد.

كما أن الهيكل اللامركزي والتنظيم الأفقي لقوات الدعم السريع، والذي يعتمد على الشبكات الاجتماعية المجتمعية القائمة، قد يؤدي إلى الانقسام وتفاقم العنف. فهيكلها الشبكي لا يضمن دائمًا سلسلة متماسكة من القيادة، نظرًا لأن مستوى التنسيق بين قادة الميليشيات العرقية من المستوى المتوسط منخفض. وكثيرًا ما تتعارض الأجندات المحلية والانتماءات العرقية مع الأهداف الوطنية لقوات الدعم السريع، حيث تكون التحالفات في كثير من الأحيان مدفوعة بسياسات القوة المحلية البراجماتية والمصالح الأمنية. وعلاوة على ذلك، فإن إدارة قوات الدعم السريع في المناطق الخاضعة لسيطرتها غير متسقة وغالبًا ما تفتقر إلى المؤسسات الوظيفية.[9] وقد يؤدي هذا الغياب لهياكل الحكم الفعالة إلى عدم الاستقرار وفراغ السلطة الذي يمكن استغلاله من قبل قادة قوات الدعم السريع الطموحين وقادة الميليشيات المتحالفة معهم، والذين يحرك العديد منهم مكاسب اقتصادية مباشرة – تسيطر قوات الدعم السريع على مناجم الذهب في جبل عامر في دارفور وتهرب الذهب إلى الإمارات العربية المتحدة لبيعه إلى السوق العالمية.[10]

كما يلعب تورط الإسلاميين الموالين لعمر البشير، الذين يرفضون فكرة الحكومة العلمانية ويسيطرون على مناصب رئيسية في القوات المسلحة السودانية[11]، دورًا كبيرًا في الصراع ويدفع الدول الأجنبية إلى دعم الفصائل المسلحة. فقد دفع هذا الوضع الإمارات العربية المتحدة إلى دعم قوات الدعم السريع كوسيلة لمواجهة الأجندة الإسلامية في السودان. ويمتد محاربة الإمارات العربية المتحدة للجماعات الإسلامية إلى منطقة القرن الأفريقي ومنطقة ليبيا والساحل: كما أنها تدعم القوات المسلحة غير الحكومية أو الدول التي تحارب الجماعات الإسلامية مثل حركة الشباب وتنظيم الدولة الإسلامية من خلال زيادة قدراتها العسكرية أو توفير التدريب والأسلحة.[12] وفي السودان، تشير التقارير إلى أن الإمارات العربية المتحدة، التي تدعم قوات الدعم السريع، هي اللاعب الأجنبي الأكثر استثمارًا في الصراع.[13] وبالإضافة إلى مواجهة الحركة الإسلامية، تخدم قوات الدعم السريع مصالح الإمارات العربية المتحدة من خلال توفير المقاتلين للمعارك ضد الحوثيين في اليمن ومساعدة الجنرال/ خليفة حفتر في ليبيا، مما يسمح لقوات الدعم السريع بتوسيع عملياتها على طول الحدود مع ليبيا وجمهورية أفريقيا الوسطى.[14] وبالتالي، فإن المساعدات التي تقدمها الإمارات العربية المتحدة لقوات الدعم السريع تهدف إلى تشكيل المشهد السياسي في السودان والتأثير على المنطقة الأوسع لكبح الحركات الإسلامية وحماية الإنتاج الزراعي للإمارات العربية المتحدة في السودان لتلبية أمنها الغذائي. وترغب الإمارات العربية المتحدة في ربط استثماراتها الزراعية في السودان بميناء أبو عمامة على البحر الأحمر، حيث استثمرت هناك حتى الآن أكثر من 6 مليارات دولار.[15] ويتفق العديد من الخبراء على أن استمرار دعم الإمارات العربية المتحدة لقوات الدعم السريع يؤدي إلى استمرار الصراع.[16] ومن المرجح أن يؤدي هذا الدعم الثابت إلى إطالة أمد الصراع، مما يؤثر سلبًا على مفاوضات السلام.

تم إعداد هذا التقرير باللغة الإنجليزية ثم تُرجم إلى اللغة العربية. على المستخدمين الرجوع إلى التقرير باللغة الإنجليزية في حال وجود أي تناقضات.

[1] كالكيدان يبيلتال وباسيليوه روكانجا، “حصيلة القتلى في السودان أعلى بكثير مما ورد في التقارير السابقة – دراسة“، بي بي سي، 14 نوفمبر/تشرين الثاني 2024

[2] أسوشيتد برس، “الحرب في السودان شردت أكثر من 14 مليون شخص، أو حوالي 30% من السكان، بحسب الأمم المتحدة“، 29 أكتوبر/تشرين الأول 2024

[3] أيدان لويس، “الصراع في السودان: من يدعم القادة المتنافسين؟، رويترز، 12 أبريل/نيسان 2024؛ خالد عبد العزيز، وباريسا حافظي، وأيدان لويس، “الحرب الأهلية في السودان: هل تساعد الطائرات بدون طيار الإيرانية الجيش على كسب الأرض؟”، رويترز، 10 أبريل/نيسان 2024؛ صوت أمريكا، “صراع القوات المسلحة السودانية وقوات الدعم السريع يهدد الحدود الشرقية للسودان“، 1 فبراير/شباط 2024؛ سودان تريبيون، “روسيا تعرض مساعدات عسكرية “غير محدودة” للسودان“، 30 أبريل/نيسان 2024؛ أندرو ماكجريجور، “روسيا تغير موقفها في حرب السودان“، أوراسيا ديلي مونيتور، المجلد: العدد 21: 102، مؤسسة جيمستاون، 8 يوليو/تموز 2024؛ مجلس الأمن التابع للأمم المتحدة، “التقرير النهائي لفريق الخبراء المعني بالسودان“، 15 يناير/كانون الثاني 2024؛ ميدل إيست مونيتور، “الخرطوم تتهم الإمارات العربية المتحدة مرة أخرى بدعم قوات الدعم السريع“، 15 أكتوبر/تشرين الأول 2024

[4] خالد عبد العزيز، باريسا حافظي، وأيدان لويس، “الحرب الأهلية في السودان: هل تساعد الطائرات بدون طيار الإيرانية الجيش على كسب الأرض؟”، رويترز، 10 أبريل/نيسان 2024

[5] مرصد الحرب في السودان، “البرهان يرفض المحادثات مع قوات الدعم السريع في ضربة لجهود السلام“، 20 نوفمبر/تشرين الثاني 2024؛ سودان تربيون، “عودة الجيش السوداني إلى المفاوضات مشروطة بانسحاب قوات الدعم السريع من الخرطوم: بيان“، 29 يوليو/تمّوز 2023

[6] سودان تربيون، “البرهان بالسودان يتعهد بالنصر مع تقدم الجيش في الخرطوم بحري“، 28 سبتمبر/أيلول 2024

[7] راديو تامازوج، “أسئلة وأجوبة: حركة المقاومة الشعبية تدعو إلى وحدة المقاومة في السودان” 18 أبريل/نيسان 2024

[8] دبنقا، “معسكرات التدريب العسكرية في إريتريا تثير مخاوف بشأن الأمن في شرق السودان” 24 يناير/كانون الثاني 2024

[9] المقابلات التي أجراها مشروع (ACLED) بين أكتوبر/تشرين الأول 2023 وأكتوبر/تشرين الأول 2024؛ تهاني معلا، “ما وراء ساحة المعركة: “سياسات البقاء قوات الدعم السريع في السودان“، منصة مناقشات أفريقية، 14 أكتوبر/تشرين الأول 2024؛ مرصد الحرب في السودان، “قوات الدعم السريع تنشئ إدارة مدنية في غرب كردفان“، 17 سبتمبر/أيلول 2024؛ راديو تامازوج، “ورشة عمل تصدق على تشكيل إدارة مدنية في شرق دارفور الخاضعة لسيطرة قوات الدعم السريع“، 6 يونيو/حزيران 2024؛ حسن الناصر ومشاعر إدريس ومحمد ألاغرا وعمر الفاروق، “القوات المسلحة السودانية تتقدم في شمال وغرب دارفور | هلال يرفض محاولة قوات الدعم السريع فرض إدارة مدنية في أراضي دارفور | الكوليرا وحمى الضنك تستمران في الانتشار“، مدى، 19 أكتوبر/تشرين الأول 2024؛ دارفور 24، “الإدارة المدنية لقوات الدعم السريع في جنوب دارفور تدعي الحفاظ على الأمن“، 14 سبتمبر/أيلول 2024

[10] منتدى الدفاع الأفريقي: الذهب المهرب يغذي الحرب في السودان، كما تقول الأمم المتحدة. 13 فبراير/شباط 2024

[11] مرصد الحرب في السودان، “السودان يعيد الصلاحيات واسعة النطاق لأجهزة المخابرات“، 15 مايو/أيّار 2024 خالد عبد العزيز “تغطية خاصة: مصدر عسكري: الإسلاميون لديهم يد خفية في الصراع بالسودان 28 يوليو/تمّوز 2023

[12] إليونورا أرديماجني، “الدور العسكري المتزايد لدولة الإمارات العربية المتحدة في أفريقيا: “الدفاع عن المصالح وتعزيز النفوذ“، المعهد الإيطالي للدراسات السياسية الدولية، 6 مايو/أيّار 2024

[13] ياسر زيدان، “لإنهاء حرب السودان، الضغط على الإمارات العربية المتحدة“، فورين بوليسي، 29 أغسطس/آب 2024؛ حسام محجوب، “إنه سرّ معلوم: الإمارات العربية المتحدة تغذي حرب السودان – ولن يكون هناك سلام حتى نكشف ذلك“، الجارديان، 24 مايو/أيار 2024

[14] محمد مصطفى، “هل تؤجج الإمارات العربية المتحدة نيران الحرب في السودان؟، العربي الجديد، 13 أغسطس/آب 2024

[15] ألما سيلفاجيا رينالدي، “كيف أصبحت قوات الدعم السريع السودانية حليفًا رئيسيًا للمصالح اللوجستية والشركاتية لدولة الإمارات العربية المتحدة“، ميدل إيست آي، 1 سبتمبر/أيلول 2024

[16] ميدل إيست آي، “شبكة من خطوط إمداد الذخيرة، التي تدعم قوات الدعم السريع ضد الجيش السوداني، يمكن تتبعها إلى الخليج عبر ليبيا وتشاد وأوغندا وأماكن أخرى“، 25 يناير/كانون الثاني 2024

Read More

Sudan ranks eighth in the latest edition of our Conflict Index. To find out more, read our December 2024 Conflict Index results.

Nohad Eltayeb and Ali Mahmoud Ali contributed to this report.