Coding decisions on state forces, religious and ethnic minorities, arrests, and more

Published on: 2 March 2023 | Last updated: 29 November 2023

Background

The primary conflict in China is part of a broader, sustained campaign by the government to retain its firm control of power under one-party rule. This campaign takes the form of the active persecution of specific groups seen to threaten this goal. Those primarily persecuted can be defined under three broad categories: religious minorities, ethnic minorities, and activists/petitioners/political dissidents. This campaign manifests in the data primarily through arrests, forced disappearances, and attacks, as well as through the destruction and looting of places of worship, and crackdowns on protests – the latter especially in Hong Kong during the period covered.

Following pro-democracy protests in Tiananmen Square in 1989, the Chinese government has tightened its grip over freedom of speech, with mass surveillance systems that now employ advanced technologies to monitor its population. Activists and political dissidents who are critical of the government are the most common targets of this monitoring, leading to harsh, often arbitrary, punishments. In addition, despite official petitioning channels for the government to receive suggestions, complaints, and grievances from its citizens, petitioners regularly face persecution. Common responses to petitioners and activists involve hiring interceptors to abduct and forcibly repatriate them, forced disappearances, or more severe measures such as extrajudicial detentions in camps, abuses, assaults, and torture.

Meanwhile, the persecution of religious minorities accompanied China’s opening and reforms in the 1980s, when religious observance in the country began to rise. Officially, China recognizes five religions, but restricts religious practice in five state-controlled patriotic religious associations under the supervision of the United Front Work Department. The revisions to the 2005 Regulation on Religious Affairs, which came into effect on 1 February 2018, emphasized national security and codified state control over every aspect of religious practice in order to “curb extremism” and “resist infiltration” (Human Rights Watch, 2018). Since its enactment, crackdowns on believers and places of worship, including state-approved associations, have reportedly intensified across all of mainland China.

Distinctly, the Chinese authorities have also stepped up their restrictions on freedom of religion, speech, movement, and the right to assembly in the autonomous regions of Tibet and Xinjiang (majority Buddhist and Muslim, respectively), which have been justified as responses to fight “terrorism” and “separatist movements”. The “Regulations on De-Extremification” adopted in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in March 2017 define 15 manifestations of Islamic extremism, and call for the use of political re-education, or “transformation through education” against Islamic extremism (China Law Translate, 30 March 2017). Numerous detention facilities have since been set up within the region, with an estimated one million people arbitrarily detained in these facilities and forced to study Chinese laws and policies (Amnesty International, 2018).

Lastly, China’s campaign to retain and expand one-party rule is possibly most recognizable through 2019-2020 in the Special Administrative Region of Hong Kong, where protests sparked by the now-withdrawn extradition bill (first proposed in February 2019) quickly escalated to unprecedented levels of violence in the city. Widely regarded as a sign of the Chinese central government’s encroachment on Hong Kong’s autonomy1 Hong Kong’s autonomy is defined by the Sino-British Joint Declaration, which outlined the provisions by which Hong Kong would retain its former economic and political systems for 50 years. and a broader erosion of public trust in the Hong Kong government, the events following the announcement of the bill included large-scale demonstrations, the siege and occupation of the Legislative Council, city-wide strikes, and sieges of two universities. Allegations of police brutality and violent tactics by protesters, including the use of petrol bombs, were reported during the months of demonstrations. After the controversial bill was formally withdrawn in October 2019, the protests broadened to become a call for the Hong Kong government to meet the Five Demands.2 The Five Demands are: Full withdrawal of the extradition bill from the legislative process; Retraction of the characterisation of the 12 June 2019 protests as “riots”; Release and exoneration of arrested protesters; Establishment of an independent commission of inquiry into police behavior; Universal suffrage for Legislative Council and Chief Executive elections. Further signs of eroding public trust were witnessed following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, where improvised explosive devices were planted in several locations between January and February 2020 after the government failed to close the city’s border and supply protective gear.

China has presented a number of methodological challenges for the tracking and recording of disorder. These primarily concern media coverage – given the government’s strict control over mainstream mass media – with a lack of access to credible and accurate reporting for events in China.

How does ACLED code Taiwan (ROC) as a territory?

A number of sections in this document will differentiate between China and Taiwan when explaining how certain actors and locations are sourced and coded. This is because ACLED codes the Republic of China (ROC) as separate from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in regards to both the Country variable, as well as the lower administrative divisions. A number of factors have helped inform this decision:

- Unlike in de facto states (e.g. the Republic of Artsakh, or the Republic of Somaliland), where political violence occurs either on the border or across borders with some regularity, conflict trends in Taiwan (ROC) are distinctly separate from those in mainland China (PRC) – both politically and geographically – and thus warrant the inclusion of a separate country dataset.

- While only officially recognized by a handful of international states, Taiwan operates unofficial diplomatic and economic missions through their “Taipei Economic and Cultural Representative Offices” in nearly 60 countries, including the United States (ROC Bureau of Consular Affairs, 2020).

- In regards to the lower-level administrative divisions, reports overwhelmingly use the ROC-created divisions when reporting on Taiwan as opposed to the PRC-created divisions, thus making their use an obvious choice in a geo-referenced dataset.

In short, coding Taiwan as such acknowledges the fact that a distinct governing authority exists in Taiwan with a significant level of informal international recognition, and that the cultural and political trends differ significantly from those in the PRC.

How does ACLED code certain actors in China and Taiwan?

A number of unique actors are present in the Chinese and Taiwanese data, among them sub-divisions of security forces, a small number of political militias and rebel groups, triad groups directly engaging in political violence, and unique associated actors to civilians and demonstrators.

State Forces of China (PRC)

ACLED codes specific sub-groups of state forces in cases when it is deemed analytically useful. Normally, this occurs in regions where a) the sources consistently differentiate between sub-groups; and b) the sub-groups engage in distinct types of events (e.g. terrorism task forces, gang violence units, military police, etc.). In some cases, an autonomous region within a state will also receive their own state actors, denoting a level of independence and anticipating events in which autonomous state forces may engage with other state forces.

In the PRC, ACLED codes separate state unit actors for Hong Kong and Macao, both Special Administrative Regions with some level of autonomy. The actors are as follows:

For Hong Kong, these include:

- Police Forces of China (2016-) Hong Kong Police Force

- Military Forces of China (2016-) Hong Kong Garrison

- Government of China (2016-) Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

For Macao, these include:

- Police Forces of Macao (2017-) Macao Police Force

- Military Forces of China (2017-) Macao Garrison

- Government of China (2017-) Macao Special Administrative Region

In mainland China, two police actors are used: the standard Police Forces of China (2012-), and the Police Forces of China (2012-) People’s Armed Police, which is a more specialized branch responsible for riot control, anti-terrorism, and disaster response, among other things. For military forces, ACLED uses a single actor: Military Forces of China (2012-). Government officials and the state as an institution (for more symbolic events like “Agreement”) use the Government of China (2012-) actor.

Security Forces of Taiwan (ROC)

Specific sub-groups are rarely mentioned in Taiwan and are thus not considered analytically important. As such, state forces in Taiwan are simply sub-divided into either Police Forces of Taiwan (2016-) or Military Forces of Taiwan (2016-). The civilian state actor is Government of Taiwan (2016-).

Non-state armed actors (PRC)3 Non-state armed actors do not play a significant role in disorder in Taiwan, and are thus not included in this section.

A number of non-state armed actors also appear in the Chinese data, although to a significantly lesser extent than in other regions of ACLED coverage. These actors are typically pro-government militias or criminal groups hired by the state, though the majority are unidentified by the source.

Unidentified armed groups (UAGs) are present throughout the ACLED dataset, the result of a source’s inability, or unwillingness, to identify specific armed groups. There are a number of reasons why a group may be “unidentified”; these are outlined in ACLED’s analysis of UAGs in conflict zones.

In China (PRC), the Unidentified Armed Group (China) actor is used in a number of situations. However, the majority of events featuring this actor involve the abduction of, or attacks on, petitioners, activists, or minority leaders. The Militia (Pro-Government) actor is used in similar situations, but where the association with the state is more defined by the source. See the Actors in Abduction/forced disappearance events section below for more details on both groups.

Triad groups also appear in the Chinese data, although only in certain circumstances. ACLED’s standard interpretation of gang activity dictates that it qualifies as political violence only when it has direct political targets and/or is used for political purposes.4 Some exceptions to this rule have been made for several countries with extreme criminal violence in Latin America, as defined in ACLED’s methodology on gang violence. As a result, violence by Triads is only captured when the targets are political actors (again typically petitioners, activists, or minority leaders). Because specific Triad groups are rarely mentioned by the source, the Unidentified Triad Group (China) actor is used. ACLED is conservative with its application of this actor, requiring direct association with a Triad group, or members of “black society”. References to “gangsters” or “thugs” without further qualifiers are coded as either an unidentified armed group or a pro-government militia, depending on the factors noted above.

Unique associated actors

The Five Demands Movement is an associated actor used to define demonstrators in Hong Kong acting as part of the broad protest movement beginning on 9 June 2019. While one of the five demands, the withdrawal of the Extradition Bill, was met on 4 September 2019, this associated actor continues to be used as a means to maintain analytical consistency.

How does ACLED code arrests, abductions, and forced disappearances in China?

Arrests

In China, events are often reported involving law enforcement authorities arresting civilians who petition for their rights, speak out against the state, or are part of religious groups. By default, reports of people being “taken away” (抓走、带走) by law enforcement agencies (i.e. officers from any public security agencies/公安机关) are treated as arrests (even if the arrest is arbitrary/politically motivated) and would not be coded unless it meets at least one of the following criteria:

- It involves a high profile political figure or activist/movement leader (e.g. Joshua Wong)

- 25+ people are arrested in one place at one time

- 100+ people are arrested in a broader area or across a longer period of time. For example, if 35 people are arrested over 3 days, it would not be coded. On the other hand, if 1000 people are arrested over a week in one city/district, it would be coded as a single event at the capital of the city/district with a time-precision of 2).

Events meeting one of the thresholds above are coded as event type “Strategic developments”, sub-event type “Arrest”.

Note that the average human rights lawyer or activist is generally not considered a “high profile” political figure. As such, ACLED would not code their arrest unless the event would be considered “Abduction/forced disappearance” instead (see section on Abduction/forced disappearance below).

A common type of detention carried out by law enforcement officers is referred to as “Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location” (RSDL)/指定居所监视居住. Reports of people being held under this provision are coded under the “Abduction/forced disappearance” by default (see below).

House Arrests

Reports of regular house arrests or “soft detentions”/软禁 are treated as regular arrests. These include instances of people being monitored/surveilled (physically and/or remotely; e.g. with tracking devices) and detained within their homes or other known locations by law enforcement officers. Such events are treated as such, regardless of whether a specific reason for the detention is reported. If violence is used against the individual(s) being detained, the event is then treated as an “Attack”.

Mass Arrests

Occasionally, authorities carry out coordinated mass arrests across different cities/counties within a province on different dates. In cases like this, events are aggregated as much as possible to the provincial level (geo-precision 3), as ACLED does not generally track arrests quantitatively. If a report includes a breakdown of the numbers, these will be included in the Notes column.

“Abduction/forced disappearance”

According to standard ACLED methodology, “abductions” are understood to be any form of capture, kidnapping, or hostage-taking against civilians perpetrated by armed groups other than state forces. On the other hand, “forced disappearances” can be understood as non-judicial “kidnappings” carried out by state forces.

When it comes to state forces, the line drawn between the “Arrest” and “Abduction/forced disappearance” sub-event types is largely based on context. As a general guideline, ACLED assumes a case is a “forced disappearance” when the surrounding circumstances of an arrest fall outside of judicial limits.

The following is a non-exhaustive list of some common situations in China where detentions carried out by state forces are coded under the “Abduction/forced disappearance” sub-event type (i.e. they are assumed to fall outside of judicial limits):

- People being held incommunicado (i.e. unable to be contacted/held in an undisclosed location).

- Common terms identifying such events include: 失联、下落不明、杳无音信等。

- People being detained by non-law enforcement personnel, but who are state-backed, including:

- Government officials who do not have formal law enforcement capacity (e.g. the local mayor or party secretary)

- Private security forces or “thugs” (黑保安或维稳打手) hired by the government

- People being sent to any version of a “political re-education” camp

- People being forcibly admitted into mental hospitals by authorities (e.g. 强迫医治、被神经病)

- People being held in any version of a “black jail”/黑监狱. Briefly, “black jails” can be understood as irregular/extralegal detention centers.5 Detentions in black jails differ from house arrests in that the former typically involves incommunicado detention and abuse, while the latter primarily involves surveillance and some restrictions to freedom (degrees might vary). It is generally clear from the reporting when a detention is considered a typical house arrest or if it is being carried out in a black jail (e.g. if the report says 软禁, ACLED treats it as a house arrest unless the detention is incommunicado or has other “questionable” aspects). Common locations used by state forces as “black jails” are hotels, resorts, and hospitals.6 The most famous “black jail” is arguably the Relief Service Centre in Majialou, Beijing/马家楼接济服务中心, more commonly referred to as Majialou/马家楼.

- People being placed under “Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location” (RSDL)/指定居所监视居住.

- This form of detention is considered legal within the state and is undertaken by law enforcement7 Article 75 of China’s Criminal Procedure Law, but, by definition, it is enforced disappearance, as it allows people to be detained incommunicado in extralegal detention centers indefinitely.

- Being “taken on mandatory vacation”/被度假 is commonly used as a euphemism for temporary enforced disappearance, and it is usually interchangeable with RSDL. Reports of this are coded as “forced disappearance” as well.

Actors in “Abduction/forced disappearance events”

A variety of actors carry out “Abduction/forced disappearance” events in China. The following is a list of common perpetrators appearing in the data:

- Any state actor or group/individual formally employed by the state is coded as Police Forces of China.8 The key distinction here is that if law enforcement officers take people away, the default action would be to treat such an event as an “Arrests” sub-event type unless there are extrajudicial elements surrounding the event. However, if non-law enforcement state actors detain people, the “Abduction/forced disappearance” sub-event type would be the default option.

- If private security forces (e.g. 黑保安) are hired by the state, Actor 1 is coded as Private Security Forces, with Associated Actor 1 as Government of China.

- If “thugs” or “gangsters” are hired or sanctioned by the state, Actor 1 is coded as Militia (Pro-Government).9 ACLED methodology defines pro-government militias as violent or armed political organizations/groups that assist regime and state elites through illicit violence. Groups that are non-official, but nonetheless state-sanctioned or carry out orders of the state (e.g. gangsters hired by the government) would generally be coded as Militia (Pro-Government).

- If “Triads” or members of “black society” are specifically mentioned, and are engaging in the abduction of a political target, Actor 1 is coded as Unidentified Triad Group (China). If the group is also noted to have been hired or sanctioned by the state, Associated Actor 1 is coded as Government of China.

- If the report does not mention an actor, or if the identity of the actor is unclear, the perpetrator is coded as Unidentified Armed Group (China).

The actors above typically target the following groups of people:

- Human rights defenders (维权/维权人士)

- Petitioners

- Political dissidents

- Ethnic/religious minorities. Here, the relevant ethnic/religious groups are coded as associated actors. A non-exhaustive list includes:

- Buddhist Group (China)

- Christian Group (China)

- Muslim Group (China)

- Uyghur Ethnic Group (China)

- Kazahk Ethnic Group (China)

- Tibetan Ethnic Group (China)

Locations in “Arrest” and “Abduction/forced disappearance” events

For “Arrests” and “Abduction/forced disappearance” events, the Location of the event is coded at the location from which the individual was initially taken. If this cannot be determined, either from direct reference, clues in the reporting, or from further research, then the appropriate provincial capital is coded at a geo-precision of 3. If the location of the event cannot be determined to at least the provincial level, the event cannot be coded. This is consistent with ACLED’s methodology on the geo-precision of events.

What events are not coded as “Arrests” or “Abduction/forced disappearances”

It is a common tactic for state-backed actors to force people to go home while they are en route to petition (either at the provincial government or in Beijing) or to attend a protest demonstration. These events would generally be considered intimidation events and would not be coded unless there is mention of violence being used, or some form of detention that would qualify it as an abduction (see preceding sections).

Note that the keyword here is that people are on their way to a destination. If they have already gathered as part of a demonstration before being forced to go home, this would be coded under the “Protest with intervention” sub-event type instead. Likewise, if it is clear that people are marching as part of a demonstration across an area (a state, a district, or from one city to another), and they are forced to go home during the protest march, it would also be coded as “Protest with intervention”.

If any violence is reported in addition to an abduction or arrest (e.g. beatings, torture, serious injuries, or fatalities) the event is instead coded under the “Attack” sub-event type. Reports of torture or abuse in police custody10 This includes cases in which individuals are reportedly forced to take clearly harmful drugs, or are intentionally placed in situations likely harmful to the individual (e.g. unheated rooms, little to no access to food and water, etc.) are also treated as an “Attack” (see below).

How does ACLED code violence and persecution against religious and ethnic minorities in China?

Attacks

While abductions and arrests are more common in China, attacks on civilians of religious or ethnic minorities do occur, particularly by state forces and pro-government militias. ACLED codes a number of circumstances under the “Attack” sub-event type:

- Excessive violence during raids or demolitions (e.g. the head of a Buddhist temple is dragged out and beaten by police for “holding religious activities without approval”. The temple is demolished).

- Civilians are tortured or beaten while in state custody (e.g. a member of the Church of Almighty God in Chongqing is beaten by the police during her custody after refusing to provide information about the Church during interrogations).

- Civilians are placed in prison situations in which their health is jeopardized as a result of the withholding of medical care, food, water, sleep, or heat (e.g. a petitioner is kidnapped by stability maintenance personnel and detained in a small room with no heating during the winter, as a result of which she caught a severe cold. She was also not given any food for two days).

Internment camps

As noted in the Abduction/forced disappearance section above, ACLED captures events in which people are sent to “political re-education” camps. Unfortunately, due to the secretive nature of such camps, violence against prisoners within these camps is difficult to access on a consistent basis. To address this, ACLED has partnered with the Xinjiang Victims Database, a group which catalogs evidence of reported mass incarcerations and abuses on minorities (most notably from the the Uyghur, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, and Hu ethnic groups) in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. While XVD’s evidence gathering process is very comprehensive, many events remain too vague for ACLED to code as discrete events. As a result, specific data on violence within these camps remains largely undocumented, and events referencing them should thus be considered as examples of a larger trend, rather than a comprehensive list of all events.

Property destruction of religious institutions

Christians and Buddhists in China are often the targets of police raids and attacks against their property. These events vary between the confiscation of furniture, statues, and crosses to the complete destruction of churches and temples. ACLED only codes these events when they meet a certain threshold of severity. Acts of vandalism and minor theft are not recorded, per standard ACLED methodology. When coded, such events are coded under the “Looting/Property destruction” sub-event type, which captures land/property seizures, property destruction, and looting by armed groups (including state forces). If any violence against civilians is reported during raids or demolitions, the sub-event type is coded as “Attack” instead (see Attack section above).

How are locations coded in China and Taiwan?

ACLED provides up to three administrative divisions for each of its country datasets. Typically, these levels are based off of official administrative boundaries. In some cases, official boundaries may not exist for higher level divisions. In other cases, ACLED may forgo including higher level divisions if they are deemed to be unuseful, such as in China, where the Admin 3 divisions are essentially the same as the Locations. Below are the administrative divisions included in the data for both the PRC and ROC.

People’s Republic of China (PRC)

ADMIN 1: Province (省), Municipality (直辖市), Autonomous region (自治区), and Special administrative region (特别行政区)

ADMIN 2: Prefectural-level municipality (地级市), Prefecture (地级行政区), and Autonomous prefecture (自治州)

ADMIN 3: Not Applicable (ACLED does not code ADMIN 3 in the PRC)

LOCATION: A populated place (city, village, etc.), natural landmark (hill or mountain, bay, etc.), or a distinct location outside the borders of a population center (military bases, rural airports, etc.)

Map 1: First Order Admin Divisions of China11 Map courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

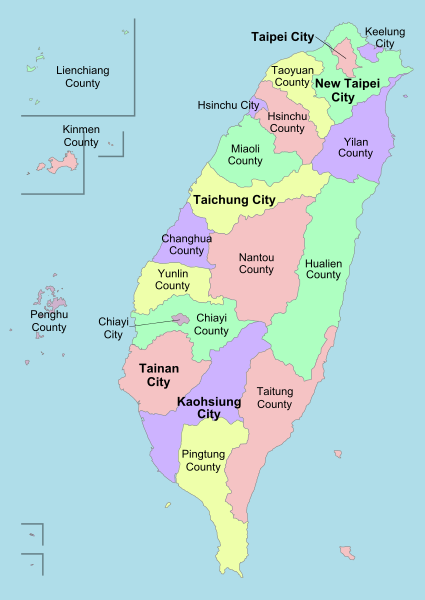

Republic of China (ROC)

ADMIN 1: County, Provincial city, Special municipality

ADMIN 2: District, Mountain indigenous district, Township/city

ADMIN 3: Not Applicable (ACLED does not code ADMIN 3 in Taiwan)

LOCATION: A populated place (city, village, etc.), natural landmark (hill or mountain, bay, etc.), or a distinct location outside the borders of a population center (military bases, rural airports, etc.)

Map 2: First Order Admin Divisions of Taiwan12 Map courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Are there locations in China or Taiwan coded below the city level?

Because of their size, the PRC cities of Beijing, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Shanghai, Chongqing, Tianjin, and Hong Kong are subdivided into their constituent administrative “districts”. Among those, the cities of Beijing, Shanghai, Chongqing, Tianjin, and Hong Kong are Admin 1 divisions, which are further divided into district-level divisions (officially Admin 2 divisions). In comparison, the cities of Guangzhou and Shenzhen are Admin 2 divisions and are further divided into their urban districts.

The naming scheme for the sub-city locations in the data follows the standard ACLED format of “City-Subdivision” (e.g. Beijing-Chaoyang), with the administrative district also appearing in the ADMIN 2 column in the cases of Beijing, Shanghai, Chongqing, Tianjin, and Hong Kong.

These city districts and counties form the exhaustive list of sub-city locations used for geo-referencing events in the above mentioned cities and no locations below the district and county level are coded. More specific information on lower level subdivisions (such as informal neighborhoods) may be found within the Notes column if specified by the source. Other cities which are also “prefectural-level municipalities” (Admin 2 divisions) have only one “city” location for the main urban area, while any separate populations centres (such as villages) within the municipality are coded as separate locations.

In the ROC, given the density of Taiwan’s population in a few key areas, coupled with its official administrative divisions and the way that locations are most commonly reported, cities which are also Admin 1 divisions are subdivided into their constituent administrative “districts” which correspond with their official Admin 2 subdivisions. This rule affects the coding of locations in the following cities: Chiayi City, Hsinchu City, Kaohsiung City, Keelung City, New Taipei City, Taichung City, Tainan City, Taoyuan City, Taipei City. The naming scheme for sub-city locations in the data follows the standard ACLED format of “City-Subdivision” (e.g. Taipei City-Da’an), with the administrative district also appearing in the ADMIN 2 column.

How are events sourced for China and Taiwan?

Each week, ACLED researchers review upwards of 70 English and Chinese (both simplified and traditional) language sources to code political violence and disorder across China and Taiwan. As a result of contrasting media environments, ACLED’s sourcing strategies differ for the two states. In all cases, ACLED develops source lists for new regions by casting a wide net, including sources from local to international, and including trusted new media and data from reputed organizations. For more information on ACLED’s general sourcing methodology, see this primer.

For mainland China, developing a balanced source list proved difficult as a result of the state’s strong control over both national and international media. For their 2020 World Press Freedom Index, Reporters without Borders (RSF) ranked the PRC fourth from last, stating that “China’s state and privately-owned media are now under the Communist Party’s close control while foreign reporters trying to work in China are encountering more and more obstacles in the field. More than 100 journalists and bloggers are currently detained in conditions that pose a threat to their lives” (RSF China, 2020). As a result, both national and subnational sources from mainland China are considerably weakened in their ability to report on disorder within China. On the other hand, Taiwan’s media environment is significantly more free, with far more issues emanating from corporate, rather than political, interference (RSF Taiwan, 2020).

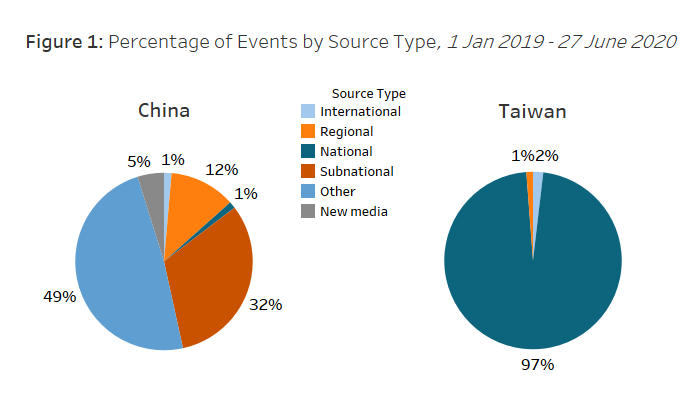

The results of these opposing media environments can be visualized using ACLED’s Source Scale column, which denotes the geographic scale of the source (if traditional media), or the type of source if non-traditional (if trusted new media, a local partner, or other). Figure 1 below depicts the sourcing profiles for both China and Taiwan based on the number of events citing each scale/type of source.13 Local partner data sources omitted from pie charts due to making up less than one percent at the time of writing.

Because of Taiwan’s size and density (see right-hand chart above), the vast majority of sources cited are national (in teal), with a mix of international (light blue) and regional (orange) sources. Earlier tests determined that subnational sources failed to capture unique events, and were thus dropped in favor of more efficient national sources, which nonetheless cover events from all administrative divisions of Taiwan. National sources such as the Liberty Times, Central News Agency (CNA), ET Today, and China Times provide the majority of data. Radio Free Asia and Asia News International provide the majority of regional coverage, while news agencies such as the Associated Press (AP), Agence France Presse (AFP), and BBC News provide international coverage.

In contrast, the Chinese sourcing profile (see left-hand chart above) demonstrates ACLED’s measures to capture data despite a lack of reliable national sources. “Other” sources (in blue) – such as reports by reputable organizations, like monitoring groups and research projects – are cited in almost half of all events in China. Further, the China Labour Bulletin (CLB), Civil Rights & Livelihood Watch (CRLW), and the human rights group Bitter Winter provide a significant number of events related to labor demonstrations as well as violence against activists, political dissidents, and ethnic and religious minorities. “New media” sources (in gray), such as the respected journalist blog Weiquanwang, report on similar issues.

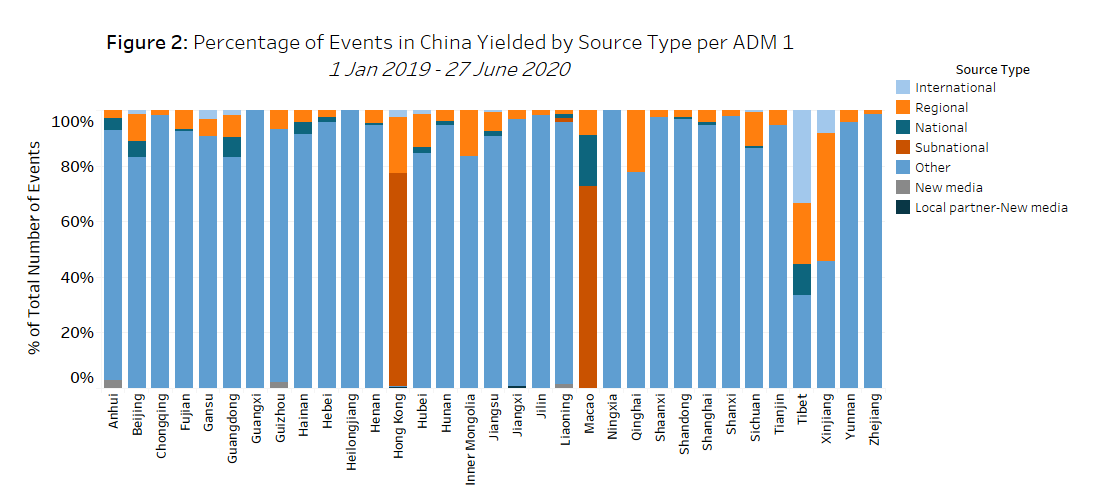

The large percentage of subnational sources (in brown) cited in the Chinese data are based in Hong Kong (and to a lesser extent in Macao), and mostly provide coverage of events that occur there. The prevalence of media in Hong Kong is a result of press freedom laws granted under the territory’s Basic Law. National sources cited for events in mainland China are often provided by sources based in Hong Kong, as well as a handful of events cited through the state-sponsored Xinhua (when corroborated by other sources). Other national sources based in mainland China, such as China Daily, Peoples’ Daily, and CCTV News were sourced for a number of months with very few results and were hence dropped. Figure 2 below illustrates the stark contrast between coverage in mainland China and the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macao. One can further note the prevalence of the use of international (light blue) and regional (orange) sources for capturing violence against ethnic and religious minorities in the autonomous regions of Tibet and Xinjiang.

Similarly to Taiwan, Radio Free Asia and international news agencies provide the majority of information from regional and international sources on events in China, with a focus on demonstrations in Hong Kong and violence against civilians in mainland China.

Furthermore, data collected by local partners can be a powerful supplemental source. Particularly in China, where media is heavily controlled and censored, particular instances of political violence may only be obtained through local networks and organizations. Having found that data on mass incarceration and violence within so-called internment camps was rarely provided through other sources, ACLED benefits from a partnership with the Xinjiang Victims Database (XVD).

As previously mentioned in the section on Internment camps above, XVD catalogs evidence of reported mass incarcerations and abuses on ethnic and religious minorities in Xinjiang. Evidence collected includes, but is not limited to, eyewitness accounts, letters from detention centers, court verdicts, local government files, and before/after photos (XVD, 2020). ACLED’s use of XVD data is limited to events categorized by XVD as “Tier 1” quality, which are those testimonies that qualify as evidence to be used in court and in rigorous reporting/research (for information on XVD’s qualifiers, see this Twitter post). As XVD has only recently introduced their tier ranking system, ACLED expects to include an increasing number of events into its dataset as XVD is able to categorize events into “Tier 1”. Some events provided by XVD are understandably limited in their time or geographic precision, meaning that ACLED cannot code them as discrete events within its standard methodology. Limitations considered, events provided by XVD nonetheless give insight into larger trends of political violence in the general regions in which they occur.

Lastly, data from ACLED’s global partners – Front Line Defenders, LiveUAMap – are used to supplement data on violence against civilians, and riots and protests.