Conflict in DR Congo continues to involve many of the usual suspects, despite efforts and ultimatums by the UN and humanitarian organizations. The UN presses on in seeking the disarmament of the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), with arguably minimal success (so far). The Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) exhibits heightened violence in the region after decreased conflict last year. Mayi-Mayi militias continue to wield significant levels of violence while grasping minimal international attention, especially relative to their rebel counterparts. And conflict in Katanga and Orientale remains while the world largely focuses solely on the eastern Kivu region. DR-Congo is far from peaceful.

The FDLR are the most active politically-violent group in DR Congo. M23, a militant rebel group founded in early 2012, with documented military and financial links to Rwanda, was largely active and responsible for much conflict in 2012 and most of 2013 until their surrender at the end of 2013. At this time, M23 announced the end of their rebellion and that they would pursue their goals “through purely political means” thereafter[1]. In 2014 the M23 have been involved in markedly fewer conflicts, though the UN continues to appeal to Congolese authorities for justice for crimes committed by the group at the height of their power.[2] Reports of recent reassembly and recruitment have yet to produce a significant increase in violent activity.

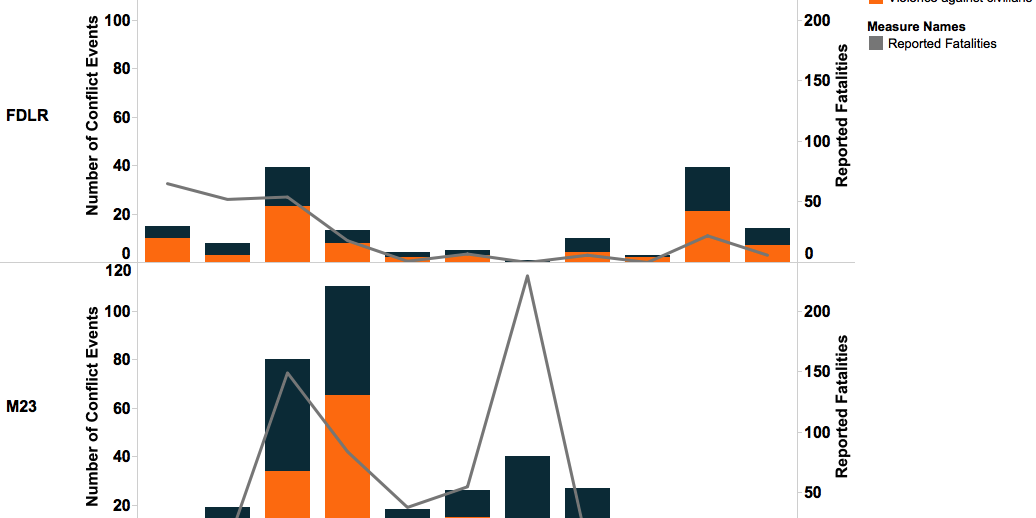

The long shadow of Rwanda continues to exert the dominant influence in Eastern Congo’s conflict. M23 was a predominantly Tutsi group while the FDLR is primarily Hutu; both are carrying on a proxy conflict for and against Rwanda and Rwandan influences. Figure 1 shows a comparison of the two groups’ involvement in conflict since 2012. Though the M23 was involved in a higher number of conflict events, in 2013 a higher percentage of their conflict involvement was in battles. Meanwhile, tactically, the FDLR seems to divide its involvement between battles and violence against civilians fairly evenly. M23 was much more centralized in the Kivu region, exhibiting no conflict events outside of that area. Though the FDLR are also focused in Kivu, their involvement in conflict ranges across the east into Katanga province, and can also be seen in Orientale province. While the M23 was involved in battles with government forces for the most part, the FDLR is involved in battles largely with political militias. This likely stems from the fact that the M23 was formed as a mutiny of armed Congolese forces, while support from the FDLR was used by Congolese army generals in combatting the M23 at the height of their power.

UN peacekeepers have been active in DR Congo since 1999, originally as the United Nations Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo (MONUC) following the Second Congo War, and later re-deployed as the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo (MONUSCO) in July 2010. Since 2012, MONUSCO has been involved in conflicts almost exclusively with the M23 in large part in 2012 and 2013; and most recently, the FDLR. The UN has given the FDLR six months to disarm, during which time they are expected to voluntarily lay down their weapons.[3] Three months have elapsed since the ultimatum with minimal demobilization.[4] Though conflict between MONUSCO and the FDLR has decreased, at the time of writing, MONUSCO appears to be on the verge of a military offensive to eliminate the FDLR in eastern DR Congo.[5] The full effects and success of the disarmament are yet to be seen.

Since June, MONUSCO has been involved in only two conflicts, though exclusively combatting Mayi-Mayi militias (see Figure 2); these are the only instances of events in which MONUSCO has combatted Mayi-Mayi militias in recent years. In June, MONUSCO forces, supported by the Congolese military, clashed with Mayi-Mayi militias, reportedly including M23 members. In September, MONUSCO and government forces regained control of Lugunga locality from a Mayi-Mayi militia. It may be too soon to tell whether MONUSCO has taken an interest in Mayi-Mayi activity, or if these two battles simply represent old MONUSCO rivalries and attempts to maintain order in the region. Taking an interest in Mayi-Mayi militias would not be ill founded; grouped together, Mayi-Mayi militias constitute the most violence in DR Congo in 2014 of all non-government forces, as they are involved in over one-fifth of conflict events this year. These groups are political militias, emerging at different times across DR Congo. Tactically, Mayi-Mayi militias split involvement in battles and violence against civilians fairly equally. Figure 3 shows that most Mayi-Mayi battles have been against government forces, though they are also involved in a significant number of conflicts against each other / other political militias. These groups continue to be active in the east, and centered largely in Kivu. The most active of these groups in 2014 are the Raia Mutomboki, the Bakata Katanga, the Yakutumba, and the Simba, who are active in different zones around the broader Eastern Congo area. MONUSCO continues to center its operations exclusively in Kivu in 2014, despite the fact that there continues to be low-level conflict occurring in Katanga and Orientale provinces. These conflicts largely involve battles between Congolese government forces and political militias, as well as a high number of instances of violence against civilians.

References

[1] http://www.france24.com/en/20131105-drc-congo-m23-rebels-announce-end-of-rebellion-insurgency/

[2] http://allafrica.com/stories/201410101336.html

[3] http://allafrica.com/stories/201410011798.html

[4] http://christophvogel.net/2014/10/07/the-never-ending-fdlr-casse-tete/

[5] http://allafrica.com/stories/201410141239.html