Chinese influence in Africa is on the rise, with China becoming the largest trade partner of the continent (The Economist, 2015) and recently establishing its first mission to the African Union (Reuters, 2015). Chinese aid to Africa has also been increasing. This aid is intentionally distinct from other ‘traditional’ (Western) donors. While the Washington consensus may be seen as “a neo-liberal paradigm that takes into consideration democracy, good governance, and poverty reduction,” the ‘Beijing consensus’ “values the political and international relations concept of multilateralism, consensus and peaceful co-existence” (Adisu et al., 2010, p.4). Chinese emphasis on ‘South-South’ relations includes a ‘respect for sovereignty’, which is practiced as ‘non-interference’: China neither imposes its political views, ideals, nor principles onto recipient countries” (Davies et al., 2008, p.57).

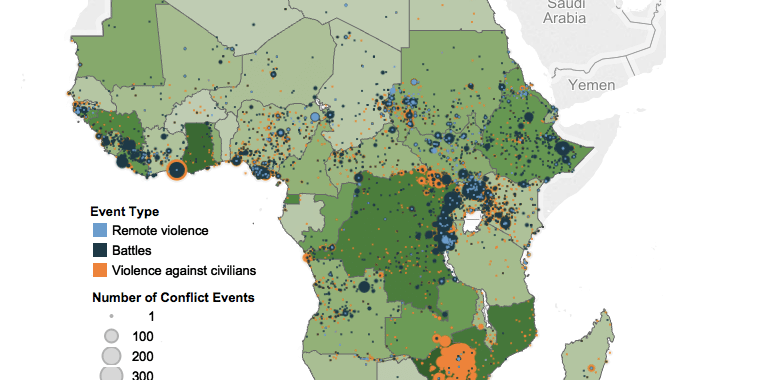

Using newly available data from the AidData project mapping Chinese aid flows in Africa, Kishi and Raleigh investigate the relationship between Chinese aid and violence in Africa. ‘Unconditionality’ is believed to make aid flows more fungible, and therefore a state’s regime can determine where such money goes without restraint. Kishi and Raleigh find political violence by the state increases when that state receives Chinese aid. While the literature on ‘traditional’ aid flows contends that aid impacts conflict through fueling rebellion – making the ‘prize’ of rebellion more attractive to insurgents – Chinese aid impacts conflict through promoting state repression. States are able to use this aid resource to repress competition, opponents and civilians. This is arguably more difficult to do with ‘traditional’, less-fungible, aid flows.

Chinese aid – as a proportion of state GDP – increases state violence against civilians, battles between state forces and competitors, and the number of locations across a state where the state practices political violence. These findings are not evident when examining ‘traditional’ aid flows. Furthermore, there is no statistically significant support for an effect of Chinese aid flows on rebel behavior or in the number of conflict actors taking up arms against the state.

These effects are not a function of specific characteristics of recipient states that may make them more prone to violence, such as autocratic institutions, resource export dependence, civil war, etc. In fact, states undergoing democratization receive a larger proportion of Chinese aid flows. This finding supports China’s agenda of non-interference and unconditionality, as Chinese aid is not targeted on attributes of the recipient state; rather, it is driven by where will be of most economic and political benefit to the Chinese. The Chinese agenda is much more amenable to African leaders who seek to remain in power, especially through repressing competition. The increased appeal by African leaders (e.g., Kenyatta of Kenya) to China over ‘traditional’ donors is symbolic of this growing trend and influence of China in the region. Though China isn’t specifically giving aid to ‘pariah states’, it is making states into pariahs through providing resources to state leaders who are not afraid to use repression as a means to quell competition.

Kishi and Raleigh’s working paper — titled “Chinese Aid and Africa’s Pariah States” — can be accessed here. Questions can be directed to rk310[at]sussex.ac.uk.

This work has been featured in Mail & Guardian Africa, the Irish Times, and Newsday on BBC World Service radio.