Violence against children is a conscious strategy employed by armed groups within conflict contexts. When children are targeted or killed, it is often in an attempt to instill terror in populations, or to reaffirm brutality and gain (global) notoriety, given that the targeting of children is meant to send a message to (adult) adversaries and/or the international community at-large. In addition to attacks, there are also numerous instances in which children are abducted and forced to fight in war. “Children are deliberately targeted as they are manipulated more easily than adults and can be indoctrinated to perform crimes and atrocities without asking questions” (SOS Children’s Villages Charity, 2015).

The indirect negative ramifications of conflict for children are also manifold – affecting every aspect of a child’s development – and can have lasting effects for years to come. SOS Children’s Villages Charity describes the short and long term impact of conflict on children:

“Children affected by armed conflict can be injured or killed, uprooted from their homes and communities [becoming internally displaced or refugees]…, orphaned or separated from their parents and families, subjected to sexual abuse and exploitation, victims of trauma as a result of being exposed to violence, [and are] deprived of education and recreation… [furthermore], it is highly probable that children living in conflict areas will be deprived of basic needs such as shelter, food and medical attention. In addition, relief for children tends to be the last priority in war, resulting in insufficient or no protection for minors. Besides, children are, due to their physical constitution and growth, most vulnerable to being deprived of food, medical assistance and education, which has a severe and lasting impact on their development” (SOS Children’s Villages Charity, 2015).

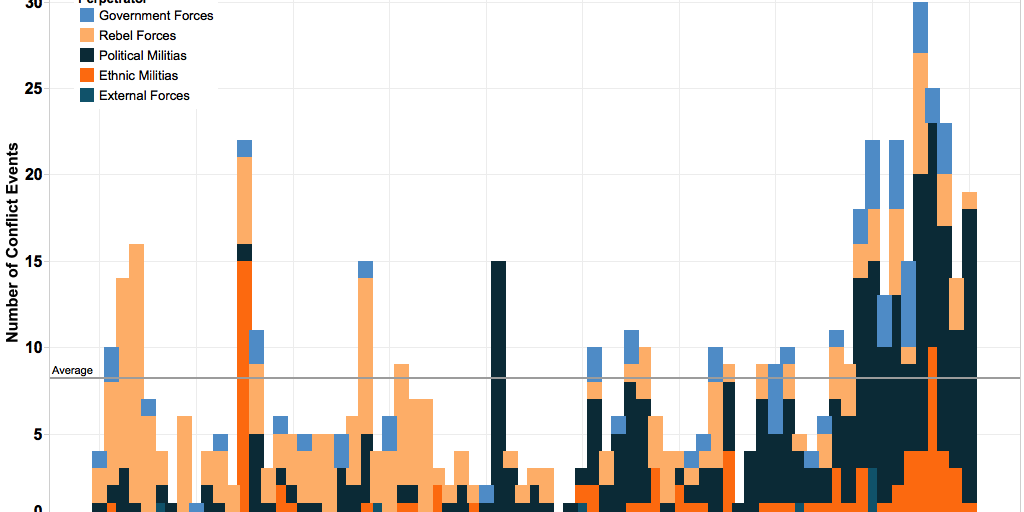

By searching for conflict events (specifically, violence against civilians) within the ACLED dataset related to children, one can gain an understanding of when and where children are targeted within conflict zones.[1] While conflict involving children has been increasing in recent years, children suffering as a result of civilian targeting has been consistently higher than average since late 2012. This is largely driven by the targeting of civilians by political militias, though government forces, rebel groups, and ethnic militias have been responsible for this violence as well in recent years (see Figure 1).

The abduction of scores of South Sudanese boys last month, forcibly recruited as child soldiers, sheds light on the violent consequences that conflict can have for children; originally 89 children were believed to have been abducted, though more recently estimates suggest that the number is in the hundreds (International Business Times, 2015; UN, 2015; UNICEF, 2015). This event also points to the role of political militias in the targeting of children – the group responsible for the abduction is believed to be a pro-government militia – though child soldiers are believed to be fighting on both sides of South Sudan’s civil war (Australian Broadcasting Company, 2015). With peace talks aimed at ending the civil war collapsing earlier this week (Agence France Presse, 2015), continued violence involving children in the region will likely continue to occur.

In addition to an increase in the number of these attacks, they have also become more expansive across Africa (see Figure 2). Figure 3 displays the proportion of these events that occurs in each state. While some states consistently show signs of this type of violence – for example, DR-Congo and Sudan – others exhibit this trend to a high degree only during certain time periods – for example, Algeria between 1997 and 2006, or Nigeria in recent years.

In a follow up blog post, the targeting of children in conflict will be further explored – specifically, the growing lethal trend of these violent events and in what contexts this type of violence occurs.

For more on violence against African children, see this piece in the Economist drawing on the data explored here.

Notes

[1] “Whilst more men tend to get killed on the battlefield, women and children are often disproportionately targeted with other forms of potentially lethal violence during conflict” (Bastick, Grimm, and Kunz, 2007). Defining armed conflict by reference to ‘battle-related deaths’ assigns increased importance to death and suffering (of men) on the battlefield, minimizing that affecting women and children off the battlefield. Unlike other armed conflict datasets, ACLED does not narrow political violence to only events surpassing a certain fatality threshold.