Unidentified armed groups (UAGs) constitute a large share of violent actors in the ACLED dataset; approximately 15% of organized, armed conflict carried out by violent actors (e.g., government forces, rebels, political militias, communal militias, external forces) are at the hands of UAGs. There are many reasons why a group may be ‘unidentified’: the first is insufficiently detailed reporting, the second is complexity within the conflict, and the third is strategic. ACLED deals with the first and second reasons by triangulating and searching in multiple sources for further details of agents involved in violence. The third reason accounts for the largest portion of Unidentified Armed Groups. Due to their anonymity, UAGs can carry out violence on behalf of conflict actors – especially those who may benefit from violence but want to avoid responsibility for those actions. Government forces, for example, may benefit from violence against civilians in order to bolster the state regime and suppress any competition; however, state regimes may want to avoid publicly taking part in these activities, especially as a result of international norms. Under these circumstances, they might utilize UAGs to do this bidding for them. These groups have many similarities to political militias, especially in that they can often act as ‘mercenaries’ and do the violent bidding of elites. These political elites (governors, political party leaders, etc.) are similar to governments in that they do not want to take open responsibility for their violent actions by name.

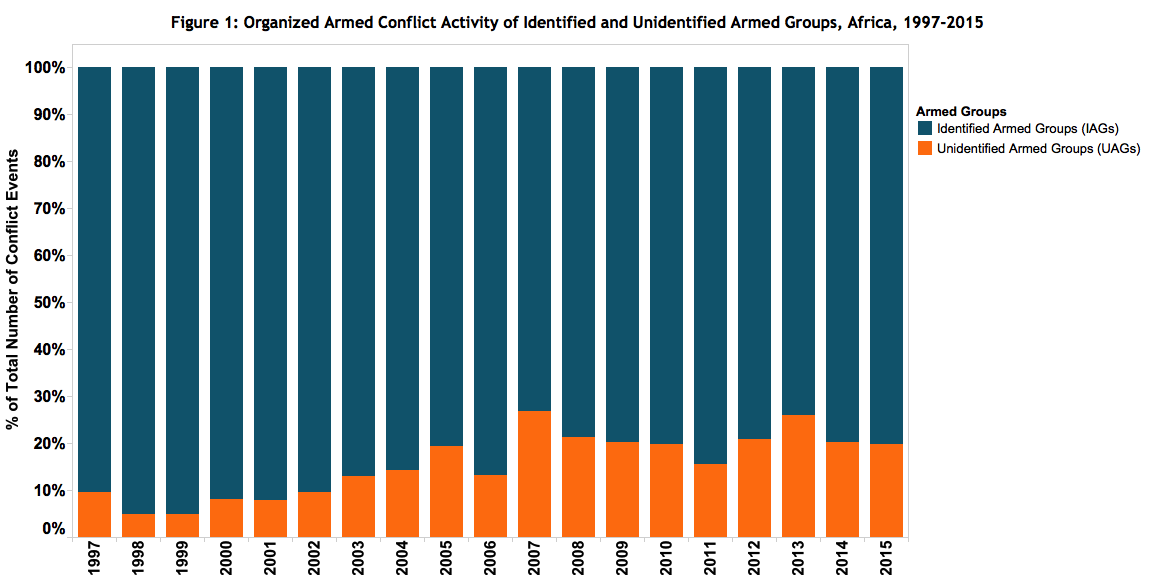

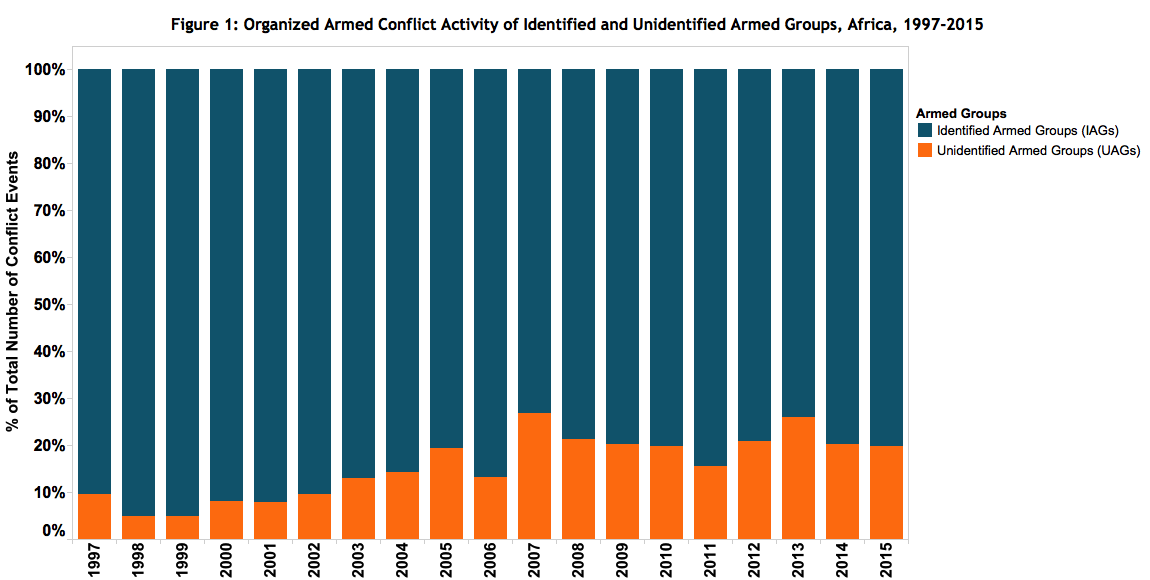

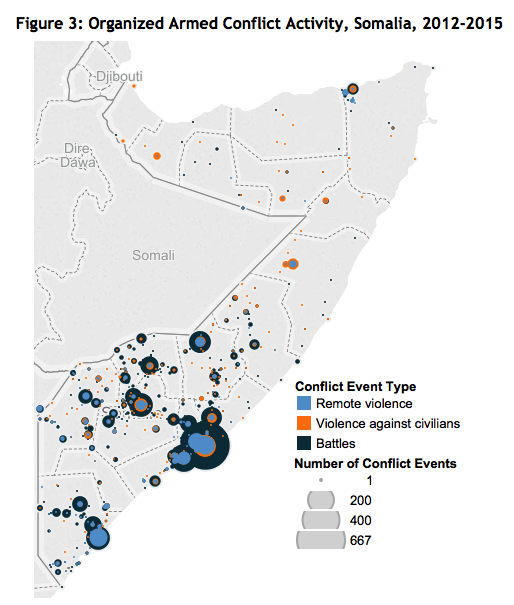

Conflict involving UAGs has been increasing in the recent decade; these groups are responsible for an increasingly larger proportion of organized, armed conflict in Africa (Figure 1). Most events involving ‘unidentified’ groups occur in in Somalia (Figure 2). In Somalia, while the behavioral trends of identified versus unidentified groups are similar over time, there is a deviation in conflict battles involving identified groups since 2010 – in line with the major push for regaining the capital from Al Shabaab by the ‘Transitional Government Forces’ – now Government of Somalia – backed by the US and regional powers including Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda. Late 2010 and the associated external intervention are arguably the major turning points in Somalia’s two decades of conflict.

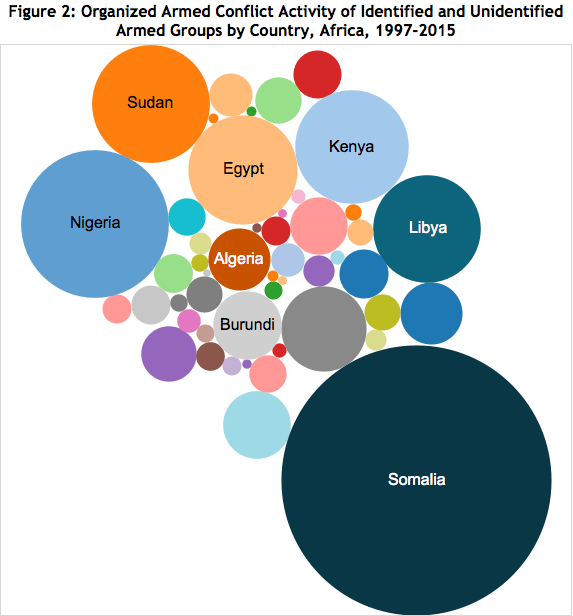

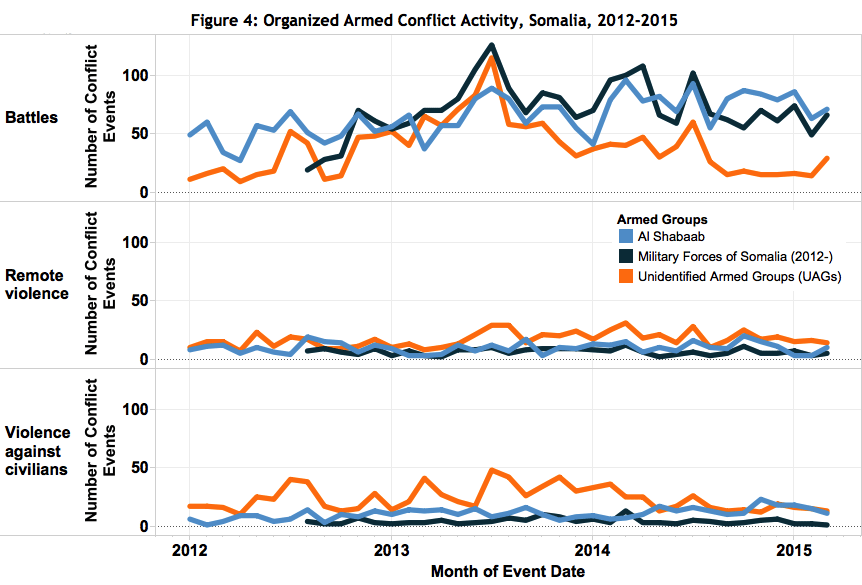

Figure 3 is a map of the locations of conflict activity involving government forces, Al Shabaab, and UAGs in Somalia. Remote violence and civilian targeting tend to occur in the same locations as civil war battles, suggesting that the same/aligned actors may be involved. Figure 4 displays the conflict activity of government forces, Al Shabaab, and UAGs in recent years. As expected, government forces and Al Shabaab are most active in conflict battles – i.e., civil war conflict activity. UAGs and Al Shabaab feature more prominently in the use of remote violence and civilian targeting tactics in Somalia.

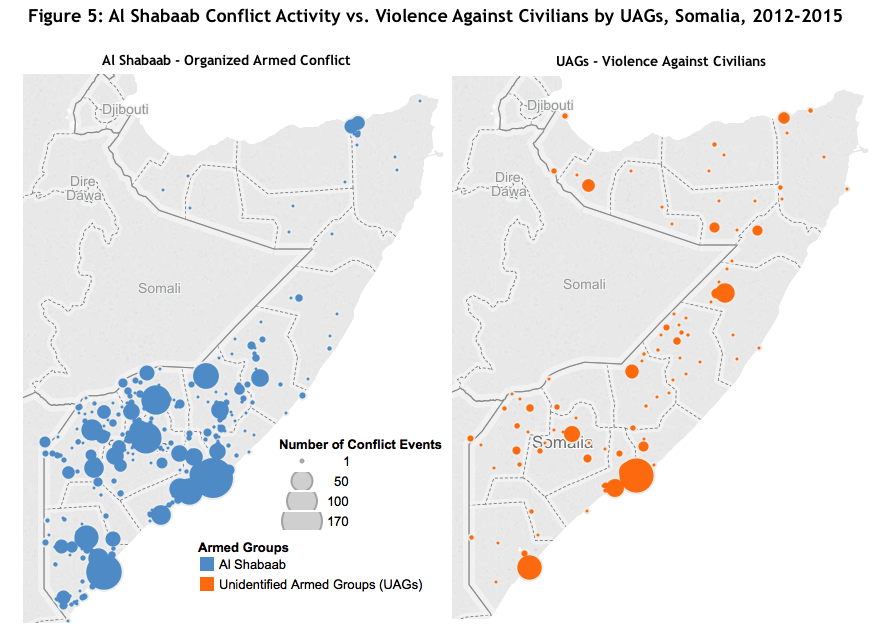

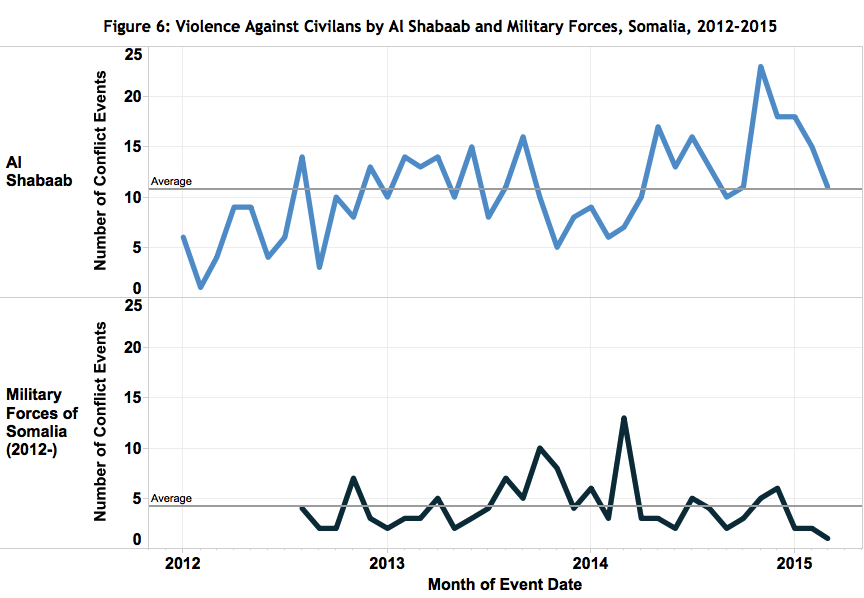

In previous years, when Al Shabaab was dominant, their rate of civilian targeting was low. The rate of civilian targeting by UAGs, however – especially in the same spaces in which Al Shabaab was active – was high. Figure 5 compares maps of the locations of Al Shabaab conflict activity and UAG civilian targeting. This suspiciously low rate of violence against civilians by Al Shabaab – coupled with the high rate of this activity by UAGs in the same spaces – suggests that UAGs may have been engaged in civilian targeting on behalf of Al Shabaab. Currently, with Al Shabaab no longer dominant, they are no longer able to allocate civilian targeting to be carried out by UAGs, and instead partake in the use of this tactic themselves as they compete for territory with the Somali military. Figure 6 depicts violence against civilians by Al Shabaab, depicting higher than average rates of civilian targeting in the past year by the group. Meanwhile, a similar pattern could be hypothesized in in the use of UAGs by government military forces. The Somali military, now enjoying dominance in the conflict, could be seen as ‘contracting out’ violence against civilians to UAGs, especially in spaces that it hopes to dominate and rule. For example, last month unidentified aerial drones struck Al Shabaab strongholds in southern Somalia (Hiiraan News, 15 March 2015). Figure 6 depicts violence against civilians by the Somali military as well, and depicts the lower than average use of civilian targeting exhibited by the conflict actor in the past year.

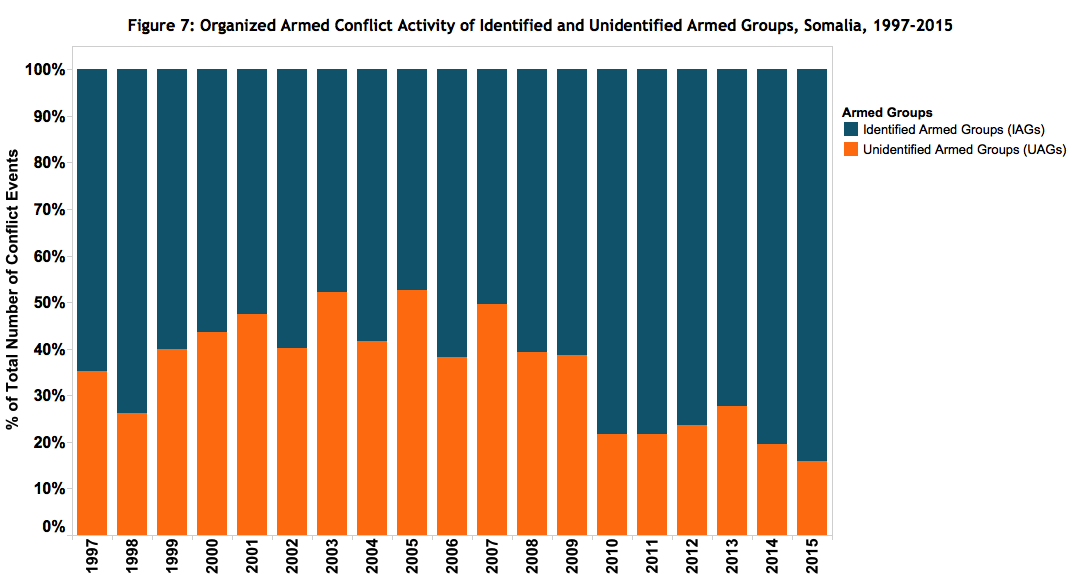

Figure 7 highlights the importance of including the conflict activity of UAGs in understanding the complete conflict landscape within Somalia – especially as UAGs make up a significant proportion of the conflict landscape: at times over half of all annual conflict activity in Somalia. Accounting for this activity is crucial in understanding the complexity of political violence, especially as a result of the strategic use of these groups within this conflict zone. Discounting the importance of conflict activity by these actors may paint the illusion of peace in what may in reality be a contentious area. See the ACLED working paper on this topic for further analysis regarding the strategic use of UAGs, especially in conflict zones.

AfricaCivilians At RiskFocus On MilitiasRemote ViolenceUnidentified Armed GroupsViolence Against Civilians