Sexual violence as a weapon of political conflict is a conscious strategy employed by armed groups to torture and humiliate opponents; terrify individuals and destroy societies, especially to incite flight from a territory; and to reaffirm aggression and brutality, specifically through an expression of domination (Bastick et al., 2007; UN, 2015).

While the primary instances of rape used as a weapon of political violence have long been centered in DR-Congo – the “rape capital of the world” (BBC, 28 April 2010) – in recent years Sudan has been breaking this trend. This year has seen the highest levels of reported sexual violence as a form of political conflict in Sudan yet. The primary spikes and instances of this form of violence are especially seen in the Darfur region.

Figure 1 depicts the number of instances of rape as a weapon of political conflict in key African countries during the past decade. It is evident that while DR-Congo previously had most reported conflict rapes in Africa, however, since 2014, Sudan has become responsible for an increasingly large proportion of these events.

[Deleted image]

In late April, Sudan finally changed a law that that led to rape victims being put on trial for adultery (a crime punishable by jail, flogging, or even stoning) (Reuters, 24 April 2015), suggesting that victims who before may not have reported sexual violence for fear of legal repercussions have begun to report such cases. Consequently, last month saw the highest number of reported cases of rape in Sudan. A counterattack has occurred due to this: late last month, security forces seized circulation of ten media outlets in Sudan in response to their reporting on sexual assaults (Reuters, 25 May 2015), suggesting that increased reporting of these cases following the seizure could be limited. Reflecting this, the graph depicts a decrease in the reporting of these events in Sudan this month. [1]

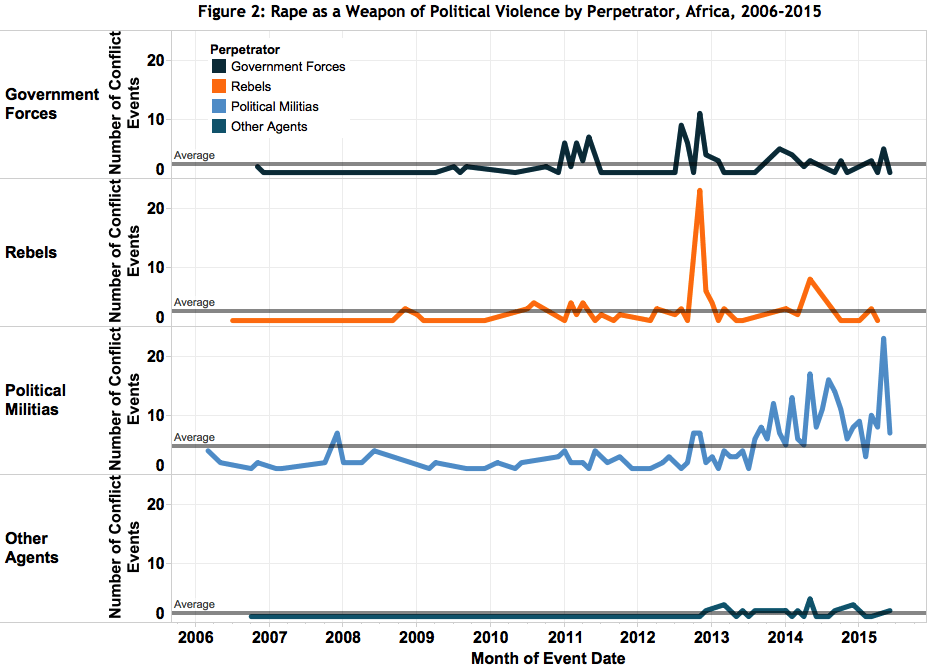

While previous spikes in the use of sexual violence across Africa were at the hands of government forces or rebel groups, since late 2013, Figure 2 depicts how political militias have pushed to the forefront for the use of this tactic, exhibiting higher than average rates of involvement in rape. Despite the decline in the use of this tactic by state militaries, government forces are not absolved of their involvement in these practices. In a recent study by Dara Kay Cohen and Ragnhild Nordås (2015), the authors argue, “militias that were trained by states are associated with higher levels of sexual violence.”

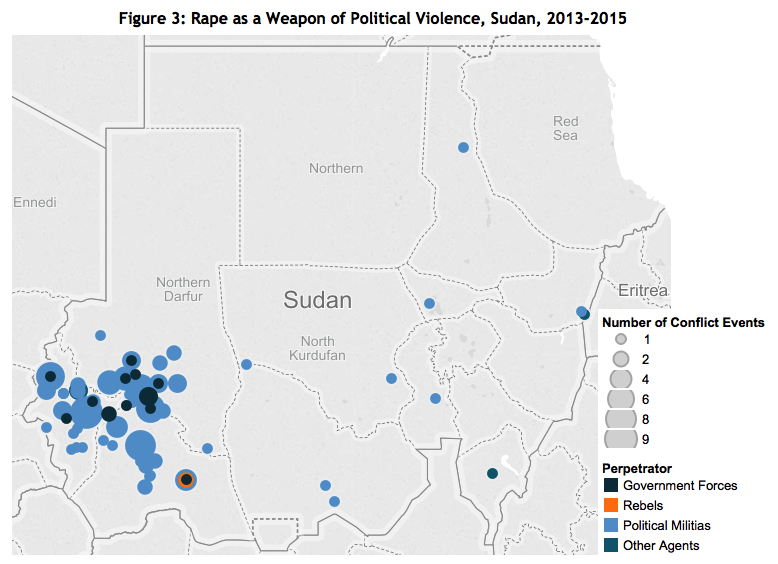

Political militias are especially active in Sudan, specifically in the Darfur region (see Figure 3). Pro-government militias and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) are the primary group(s) responsible for rapes in Sudan. Unidentified armed groups (UAGs) also largely partake in these events as well; these groups can be strategically used by government forces to carry out violence, especially due to their anonymity (ACLED, 9 April 2015).

With President Al-Bashir of Sudan – “the only sitting head of state wanted for genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity for his crimes in Darfur” (Bashir-Watch, 2015) – continuing to evade the ICC, one can expect that the conflict rape tactic will continue in Sudan. One of the multiple crimes against humanity brought against Al-Bashir is for inciting rape (BBC, 15 June 2015). Given the ‘effectiveness’ of rape as a weapon of political violence in demoralizing opposition, instilling fear in populations, and reaffirming aggression and domination, it will likely continue to be an effective tactic as long as incentives exist to engage in brutality.

For more ACLED analysis on rape as a weapon of political conflict in Africa, see part 1 and part 2 of the two-part series on the use of this violence tactic posted earlier this year.

[1] As ACLED uses reporting from media sources to code conflict events, increases and decreases in media reporting on specific topics could yield what looks like an increase or a decrease in conflict events. For more on ACLED coding practices, see the ACLED Methodology Page.