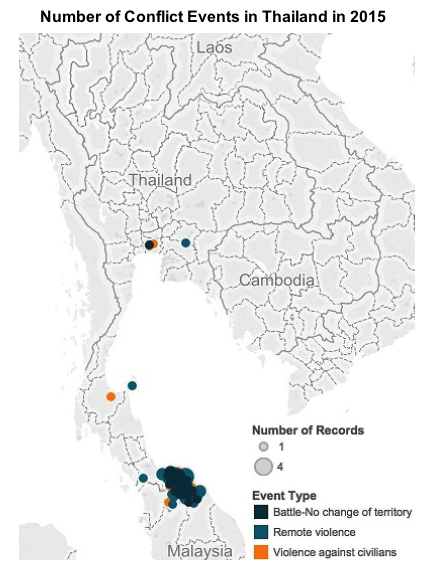

The Southern Muslim Insurgency in Thailand has grown less lethal since August 2014 (Crisis Group, 2015). In the first 8 months of 2015 there have only been 15 civilian deaths related to the conflict, whereas 2014 saw at least 50 civilian deaths (International Business Times 2014; ACLED data for 2015). However, the recent bombing in Bangkok on August 17, 2015 suggests that active Malay Muslim militants may be expanding their operations beyond the three southern provinces of Yala, Narathiwat and Pattani—collectively referred to as Patani – where they have operated for the past twelve years.

The recent bombing in Bangkok—which ripped through the Erawan Shrine, a major tourist destination—claimed 20 lives, injured more than 100 and was named one of the worst acts of political violence in Thailand’s recent history (Brookings, 2015). However, at the time of writing, it was still unknown who was responsible. While bomb attacks are relatively rare, the location and significance of this location made it an attractive candidate for terrorism.

At present, the Thai government and international experts believe three main groups could be the perpetrators, but are careful to not rule out other possibilities. The first suspects are the Malay Muslim insurgents, as some experts believe this violent conflict would eventually spill over into the capital. Others believe that targeting Bangkok, outside the southern conflict region, would be antithetical to these groups’ motives for local autonomy. In line with the recent rise in international and religiously-motivated terrorist groups, including Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State, some believe the incident could have been the work of international jihadi groups. The Thai government, however, is insistent that the bomb was not placed by an international group. Finally, the third suspects are thought to be the political elements opposed to the military junta, most predominantly the “red shirt” faction, as the bomb could have been meant to highlight the illegitimacy of the regime (Brookings, 2015). However, this seems unlikely, since after the Thai police announced a one million baht reward for information leading to the suspects, the red shirts said they would double that reward (Wall Street Journal, 2015).

In addition to the Bangkok bombing that killed 20 and wounded at least 100 more, violent incidents over the past five months indicate growing restlessness among Malay Muslim rebels. May marked a resurgence in violence as insurgents set off a wave of bombs that injured 29, including a blast on the resort island of Samui, which was the first out-of-area operation since December 2013 (CTC, 2015). June and July also saw other deadly attacks against Thai soldiers and Buddhist monks at the end of the holy Muslim month of Ramadan and the discovery of banners in southern cities that called for independence for the southern region of Patani (Deutsche Welle, 2015).

At the core of the escalated violence is a decades-old separatist movement and national liberation struggle among the Thai Malay Muslim community. For years, this community has been asserting their distinct cultural identity as separate from Thailand’s predominantly Buddhist population. The most active groups are the BRN (Barisan Revolusi Nasional), its alleged armed wing the RKK (Runda Kumpulan Kecil), the GMIP (Gerakan Mujahidin Islam Patani), the BBMP (Barisan Bersatu Mujahidin Patani), and the PULO (Patani United Liberation Organization) (East by Southeast, 2014). While these groups share a common Islamist agenda, the southern Thailand insurgency is still considered specific to Thailand and not part of the global jihad. Analysts agree that the conflict has persisted because the Thai government has shown little interest in addressing grievances. In addition to the ruling military junta’s drive to collect fingerprints and DNA from southern citizens as well as the economic and social stagnation in the south, the Malay Muslim communities have felt continually alienated (Deutsche Welle, 2015).

Peace talks began in February 2013 between representatives of the BRN and Malaysian officials though were stalled by the junta that ousted Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra on May 22, 2014. The military government has yet to initiate further dialogue (Crisis Group, 2015). If indeed Southern Muslim Separatists carried out the attacks in Bangkok and are venturing outside of their traditional conflict zones, this may indicate a radical new phase in this longstanding conflict. If insurgents intentionally spread their fight to the capital, the government may be forced to initiate a more robust military presence and/or engagement with the separatists. Although the violence witnessed in Thailand does not compare to the conflicts that dominate the global stage, the country’s consistent unrest does not appear to be close to resolution and the rising death toll—estimated at 6,500, mostly civilians—remains a cause for worry (Deutsche Welle, 2015).

This report was originally featured in the August ACLED-Asia Conflict Trends Report.