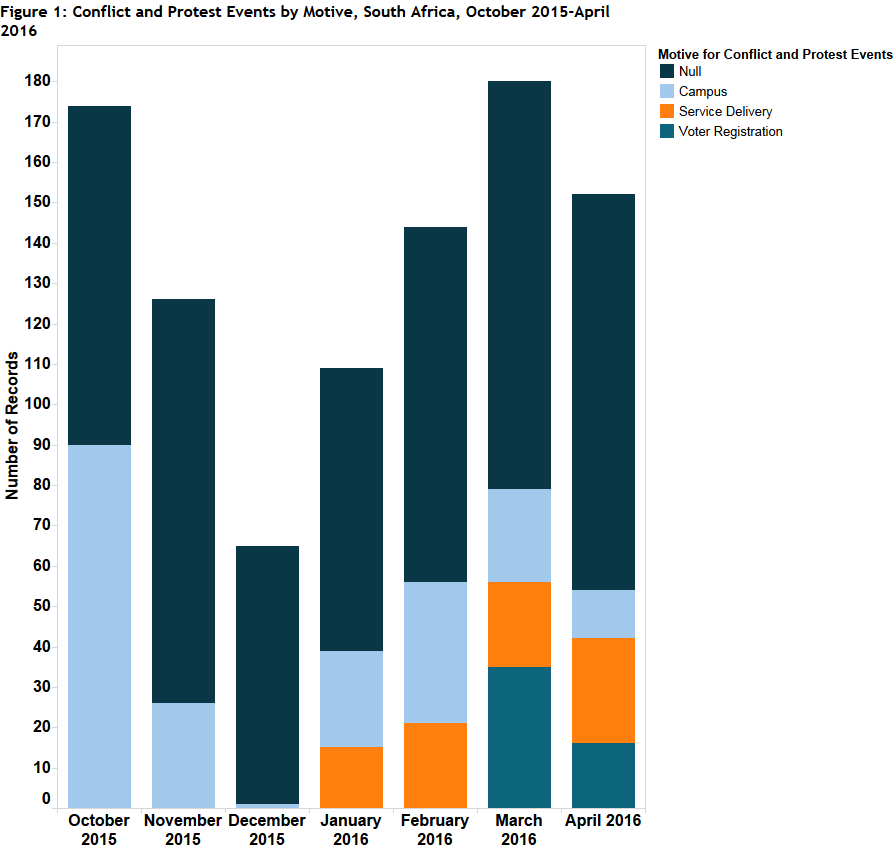

Last month witnessed a slight decrease in conflict and protest events in South Africa. Nevertheless both April and March represent the most active months in terms of political unrest since October 2015 and the nationwide student protests against fees (see Figure 1). This high level of unrest is tied to the upcoming municipal elections and continuing protests on South African university campuses.

Despite the government’s announcement to freeze university fees for 2016, protests have continued at universities across South Africa. Although university campuses have not witnessed disturbances on the scale of the mass demonstrations in October and November, university campus protests and riots continue to be a significant source of unrest, typically accounting for between 10% and 20% of monthly events. This is because in spite of the freeze, students still face significant barriers to their education. Tuition and registration fees remain in place and, when combined with living costs for a single year, still add up to more than the annual income of the average South African household (Mail & Guardian, 13 January 2016; The Guardian, 03 March 2016).

Furthermore, the issue of outsourced labour continues to galvanise both student and worker protests against university management. The #OutsourcingMustFall protests have pressured some universities – University of Cape Town, Wits University, Tufts University and University of the Free State – to review their outsourcing policies. The success of #OutsourcingMustFall at these institutions, along with the success of last year’s protests in stopping the increase in university fees and removing the status of Cecil Rhodes from UCT’s campus, indicates that protest, both violent and non-violent, is an effective mechanism of negotiating with the government and university management. If students and university workers continue to make small incremental gains on their demands, it may be the case that universities remain centres of protest in South Africa.

Protest action has marred voter registration periods for the upcoming municipal elections. No less than 51 instances of political disturbances occurred over voter registration weekends in March and April, consistent with a growing trend of demonstrations around electoral periods (Lancaster, 2016). The majority of voter registration disturbances were peaceful (57%), while over 43% of recorded disturbances involved riots or violence against civilians (ACLED Trend Report, December 2015).

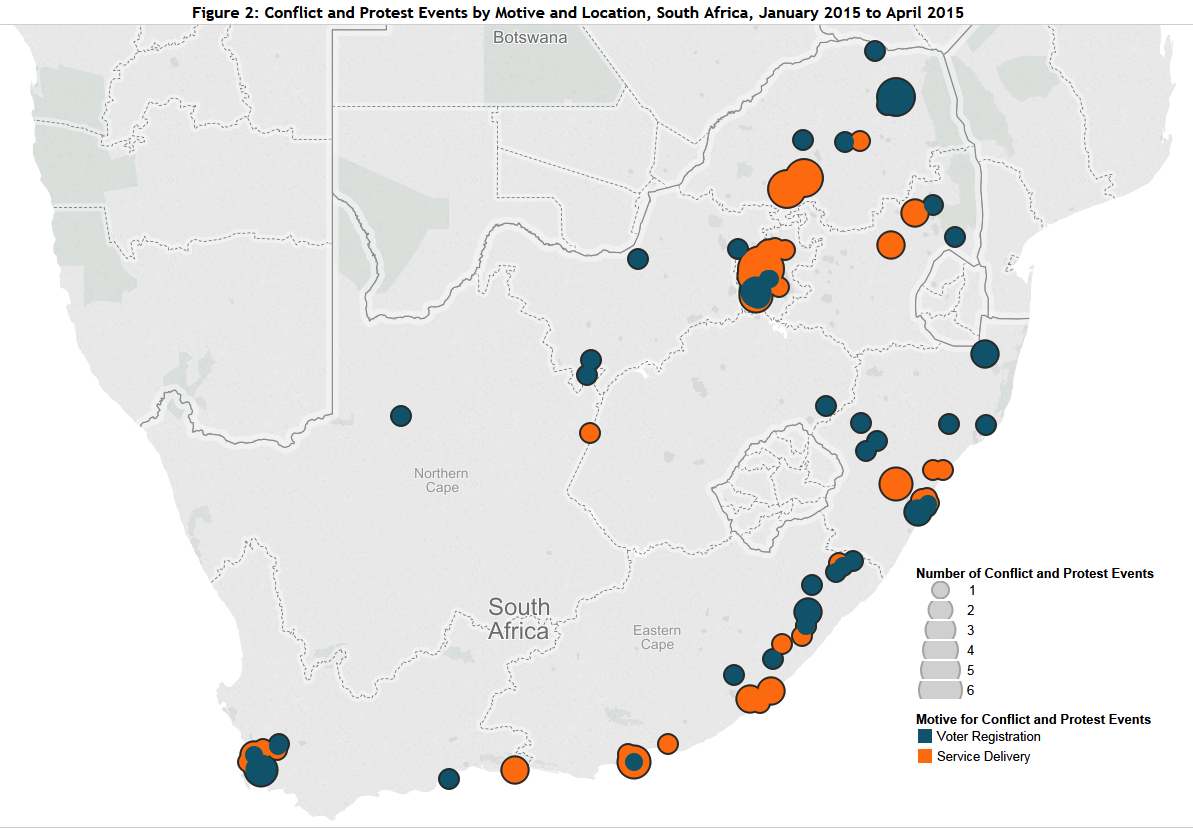

The demonstrations were largely concentrated in ANC-dominated provinces of KwaZulu-Natal, Eastern Cape and Limpopo, and more specifically ANC-controlled municipalities (see Figure 2). This concentration suggests that citizens are increasingly dissatisfied and angry with the ruling party’s inability to deliver on its electoral promises. Recent data from Afrobarometer would seem to confirm such a theory as more than 50% of South Africans feel the country is going in the wrong direction, the current economic situation is bad (Chingwete and Nomdo, 2016) and that elected leaders are performing badly (Lekalake, November 2015).

Service Delivery Protests

The unrest at voter registration centres is tied to public dissatisfaction over service delivery and municipal boundaries (Eyewitness News, 9 March 2016; Times Live, 7 March 2016). The demands of the violent protesters in Vumani and Pampierstad were centred on issues of municipal re-zoning and related issues of poor municipal service delivery (Lancaster, 2016).

Dissatisfaction with service delivery is common in South Africa, and could translate into electoral losses for the ANC. Opposition parties are feeding off recent political and economic scandals plaguing the ANC in a bid to increase their respective market shares of the South African electorate. Electoral demonstrations are a key factor of the South Africa’s political landscape in which citizens tend to vent their frustration through protest action, while concurrently supporting and voting for the ANC (Booysen, 2007). Previous research has found that South Africa’s electorate believe that ‘voting helps and protest works’ (Lancaster, 2016).

Conversely, the Western Cape, despite being host to consistent service delivery demonstrations, witnessed relatively few voter registration protests. This suggests that, despite numerous social and economic problems in the Western Cape, the electorate have a large degree of faith in the local authorities. Analysis by AfricaCheck shows that the Western Cape is the best run province and provides the greatest amount of public services such as electricity, water and sanitation (Wilkinson, 2014). As a result, the electorate of the Western Cape may not feel the need to demonstrate discontent with the local authorities or government through a refusal to vote and the destruction of electoral infrastructure.

Election Protests

While election-based protests are on the increase, it remains unknown if this form of dissatisfaction will translate into fewer votes for the ANC. As such, the upcoming municipal elections will be a crucial litmus test for ANC support but also the validity of the insurgent opposition. The established Democratic Alliance (DA) has shown its strength through the lack of voter registration protests in its heartland, the Western Cape.

Meanwhile the left-ish Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) has moved away from being a party defined by protest and disruption of the ANC establishment. The EFF recently launched its manifesto which seeks to offer an alternative to the ANC’s cadre deployment, a policy that is often tied to poor public management and service delivery, two issues that have stoked consistent protest against the ANC (Munusamy, 2 May 2016; Areff, 12 July 2012).

The unrest witnessed during this preliminary period of the electoral cycle likely indicates that there will be further instability during the August elections. EFF leader Julius Malema has announced that the opposition will remove Zuma ‘through the barrel of a gun’ should electoral fraud or state repression mar the elections (Al Jazeera, 23 April 2016).

This report was originally featured in the May ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.

Authors: Daniel Wigmore-Shepherd and Daniel Moody.