Levels of political conflict and protest in Kenya rose in the last two months. This is reversing a continued, if non-linear, trend of decreasing unrest since the country’s last elections in March 2013 (see Figure 1). The rise in political unrest has been driven by an increase in riots and protests led by the opposition Coalition for Reform and Democracy (CORD) and its leader – Raila Odinga. The source of the demonstrations is a disagreement between the opposition and the regime/Jubilee Coalition (also led by Uhuru Kenyatta) over whether the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) requires reform (Africa Confidential, 10 June 2016).

The start of these protests in April shows that the looming issue of the August 2017 general elections is already beginning to foment tension between the Kenyatta administration and CORD. Odinga and the opposition at large blame IBEC for their defeat in 2013 and argue that the organisation is biased against CORD (Otieno, 9 May 2016). The demonstrations have led to a violent response by police and security forces. There have been recorded beatings of demonstrators by police in Nairobi and police have used live ammunition against protesters in the CORD homelands of Kisumu and Siaya. The police have been open in their refusal to tolerate public dissent from the opposition and their constituents. The Nairobi County Police Commander warned the public not to demonstrate if ‘you value your lives’ (Africa Confidential, 10 June 2016).

So far ten demonstrators have been killed by police. Overall, 74% of IEBC demonstrations, violent and non-violent, have resulted in dispersal by state forces compared to 23% of all other demonstrations in 2016. This discrepancy in state repression indicates that Kenyatta is aware of the vital role a favourable IEBC will play in securing the Jubilee Coalition’s victory in 2017.

Nevertheless, the government and the opposition engaged in a national dialogue early last month, leading to a slight decrease in unrest between the 6th and 14th of June. The government acquiesced to some opposition’s key demands but the key issue is the dismissal of IEBC Chairperson Ahmed Issack Hassan, who oversaw the contentious 2013 elections. Kenyatta deemed Hassan’s dismissal as a concession too far and violence once again spiked with police shooting dead five demonstrators in Nyanza in late June (Macharia, 22 June 2016).

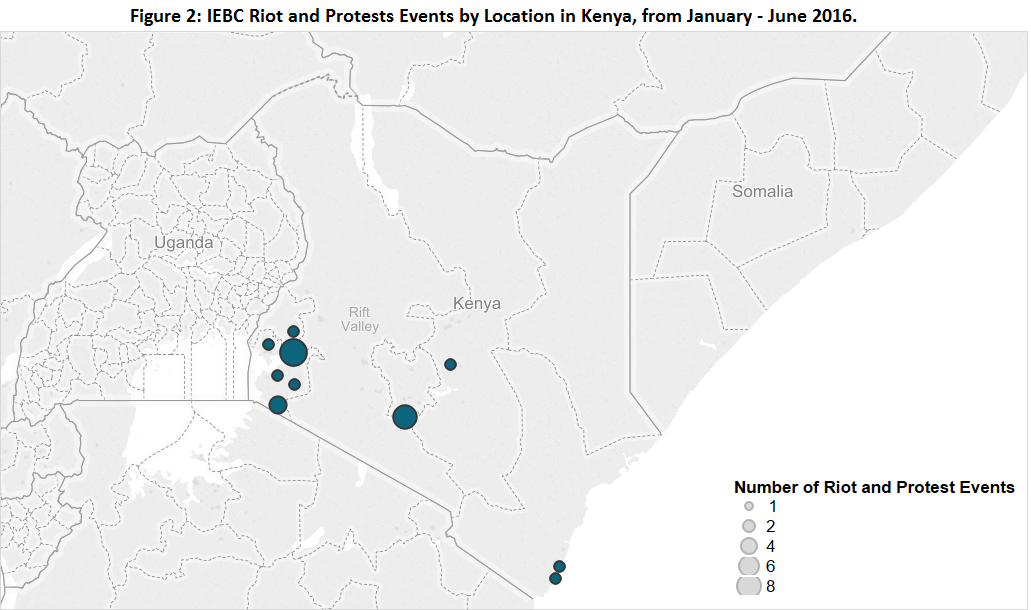

The demonstrations have been overwhelmingly concentrated in Nairobi and the Nyanza region, both strongholds of Odinga’s Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) (see Figure 2). However, there have been barely any protests in the political homelands of the other main CORD coalition partners. There are been no serious demonstrations in Kamba, the homeland of Stephen Kalonzo Musyoka’s Wiper Democratic Movement-Kenya (WDM-K), nor have there been protests in the Coast or Bungoma, the home of Forum for the Restoration of Democracy-Kenya (FORD-K).

While other senior partners in CORD have joined Odinga in his calls to reform IEBC, the lack of demonstrations in other CORD areas may reflect disunity and weakness in the coalition (Kenya Political Report, 26 June 2016). In 2013, the opposition agreed to support Odinga for a one-term presidency, to be followed by Stephen Kalonzo Musyoka or Moses Simiyu Wetangula in 2017 (Africa Confidential, 27 August 2015). The ODM argue that as Odinga did not win the election that the agreement is void and that Odinga once again should be the nominee (ibid.). Musyoka and Wetangula have both already launched their bids for the presidency (Ongera, 20 June 2016). However, lack of demonstrations in Musyoka’s and Wetangula’s home regions and the dominance of the ODM in the IEBC demonstrations shows that Odinga’s followers are more dedicated and more willing to risk violence at the hands of the state. Musyoka’s political support has been limited by Kenyatta’s incorporation of Kamba elites into senior government positions while Wetangula faces a challenge in his Luhya political homeland from former Vice President Musalia Mudavadi (Kenya Political Report, 26 June 2016). While support for the other major coalition parties within CORD remains capricious, political unrest is likely to remain concentrated within the ODM strongholds of Nyanza and Nairobi.

It is likely that the main source of political contention between the government and the opposition in the coming year will be control of the institutions that govern the electoral process. In addition to the IEBC, there has been political manoeuvrings to have a pro-Kenyatta judge take over as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court (Africa Confidential, 24 June 2016). In both the 2007 and 2013 elections, Odinga accused both the electoral authorities and the courts of impartiality and bias. While allegations of electoral fraud and a biased judiciary in 2007 resulted in the worst period of political violence since independence, in the latter case political unrest, while still high, was comparatively contained. In spite of the recent spike in demonstrations, political unrest as a whole is still well below the levels witnessed during the run up to the 2013 elections (see Figure 1), which were lauded as comparatively peaceful (ISS, 20 March 2013).

While there remains a distinct possibility of electoral violence, the fact that there are already negotiations between the opposition and government over how these institutions are run raises the possibility of compromise and reduces the probability of the electoral loser violently mobilising their constituents. However, should either party refuse to negotiate then Kenya’s trend of continually decreasing violence may be reversed.

This report was originally featured in the July ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.