A Country Report reviewing conflict patterns and dynamics, and the current state of the South Sudanese Civil War, is available here.

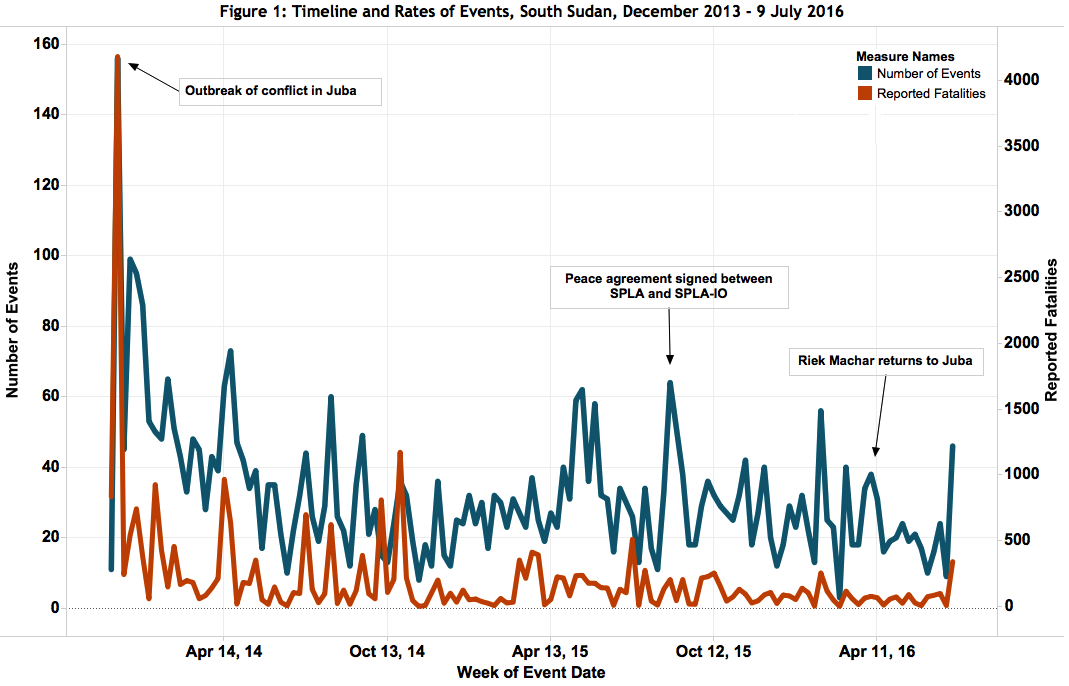

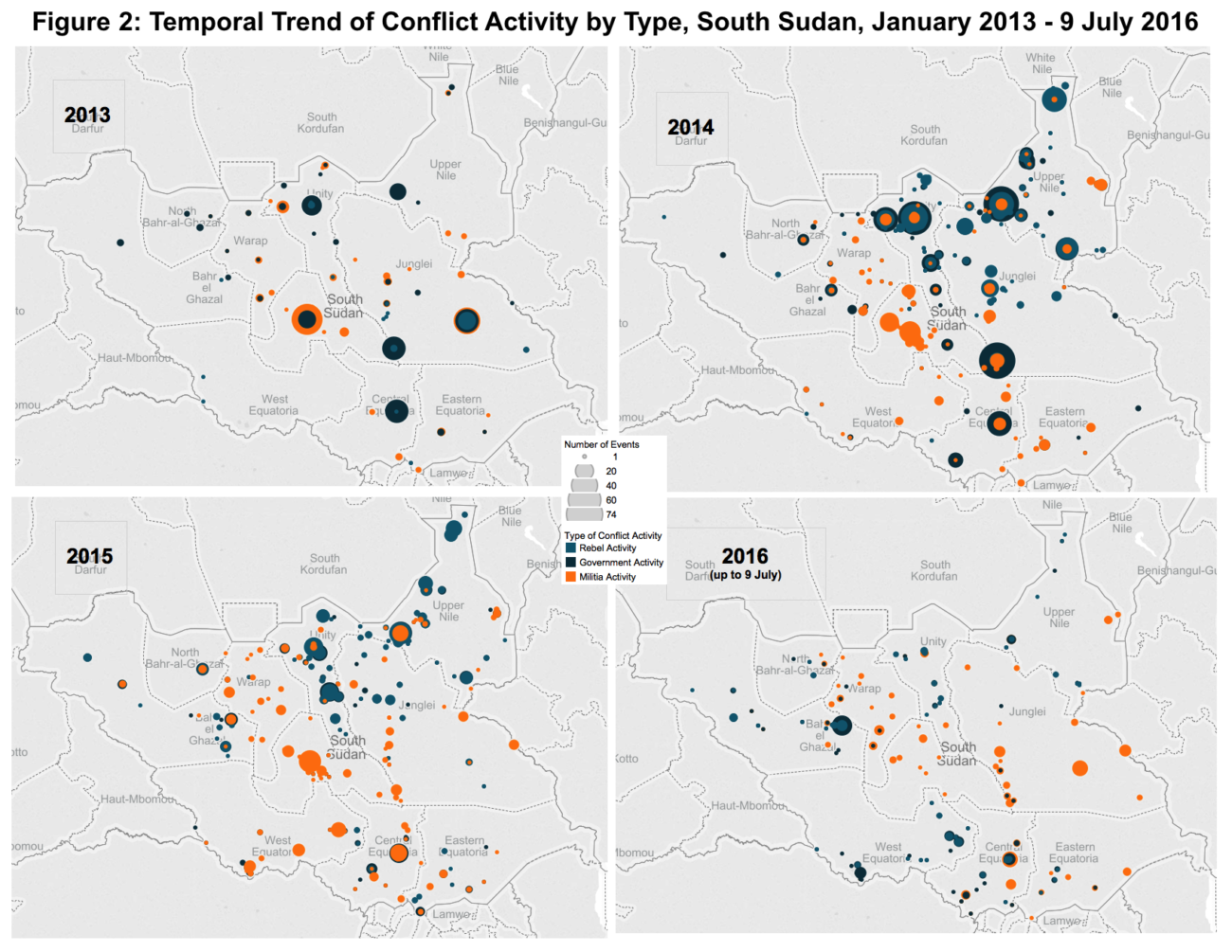

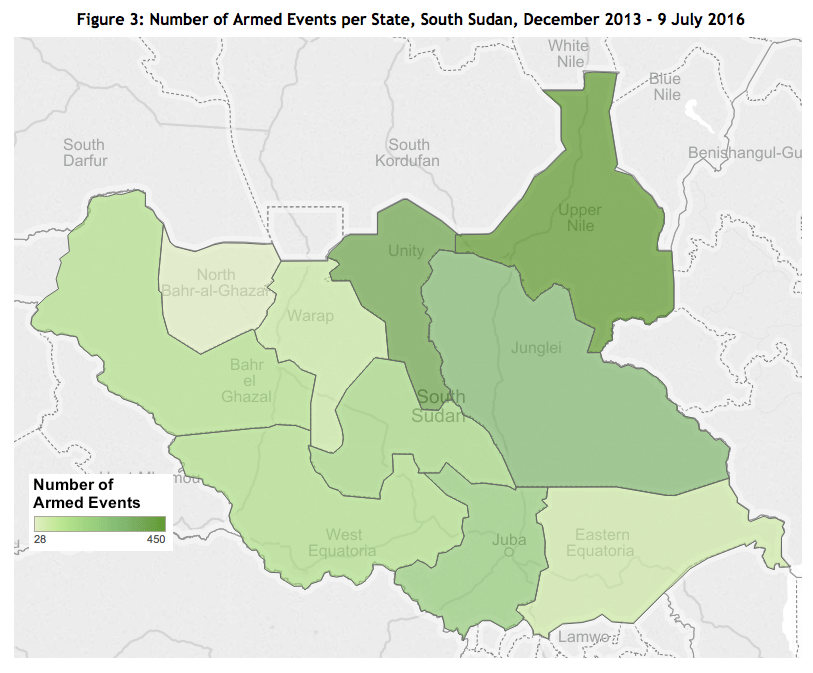

Despite both the SPLA and the SPLA-IO signing a peace agreement in August 2015, conflict has continued across South Sudan (see Figure 1). To date, almost 17,000 people have been killed in the five years since Independence; over 15,000 since the ‘civil war’ of 2013 onwards. There are multiple active conflict zones, and a recent count for 2016 suggested three rebel groups and upwards of forty active militias (both political and communal) (see Figure 2 and 3).

A recent increase in attacks across Juba is concerning mainly because of the combatants: both the SPLA (as the armed faction of both the government of South Sudan, hereafter GoSS and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-SPLM) and SPLA-IO (the Sudan People’s Liberation Army-In Opposition) are in contest again. This cleavage has dominated the civil war that has gone on nearly as long as the country’s short existence. The August 2015 peace agreement has had little effect on the actual fighting patterns throughout the state. There are important caveats to that general pattern:

- The conflict has demonstrated a shift from the north/northeast area to the south and southwest of the state over time (see Figure 2).

- There are several active conflicts throughout the state, which are linked through strategic relationships, but are loosely integrated into the dominant competition between the SPLA and SPLA-IO.

- Changing the political geography of the country through the 28 states plan has created multiple new grievances, land disputes, resource access conflicts, and opportunities for politically connected agents who want to benefit from the newly enforced distribution of resources.

A renewed focus on South Sudan is in order given the recent conflict in Juba from July 7-11; this time period coincided with the country’s fifth anniversary. There are many questions as to who is behind the violence, although that appears to be a superficial question given the highly contentious nature of Southern Sudanese politics; the level of militarization across the society at large; the ineffectiveness of the peace agreement; and the presence of high ranking, discontented elites who can benefit from further violence.

The violence is likely to have massive ripple effects, similar to the situation in December 2013. However, the agents, issues, and locations of interest have shifted somewhat to make this probable return to conflict unlike earlier instances.

The patterns of the conflict underscore that political wrangling and opportunism is behind most of the violence in Southern Sudan, and that local defense forces and militias are responsible for conducting campaigns to benefit national level elites, who have cast politics as distinctly ethnic. Despite this casting, the alliances throughout the state are not uniformly the same for ethnic communities. For instance, in some cases, sub-clans of Nuer and Dinka (the main ethnic cleavage represented by Vice President Riek Machar and President Salva Kiir, respectively) are fighting against their dominant clan association (SPLA-IO and SPLA, respectively).

This return to violence is taking place within a context of many national and local issues and grievances, including the government’s decision earlier in 2015 to postpone June’s scheduled elections in the interest of: ongoing peace negotiations; the extension of Kiir’s presidential term until 2017; and the ‘redistricting’ plan which nullifies the proposed system of power-sharing of the existing 10 states (SPLA/M-IO was to be given control of oil-rich Upper Nile and Unity States), replacing it with 28 ethnically-divided states (per Kiir’s unilateral decree in late 2015). Kiir recently agreed to allow a committee to review the borders of the 28 new states, but not to consider a reversal of the decree.

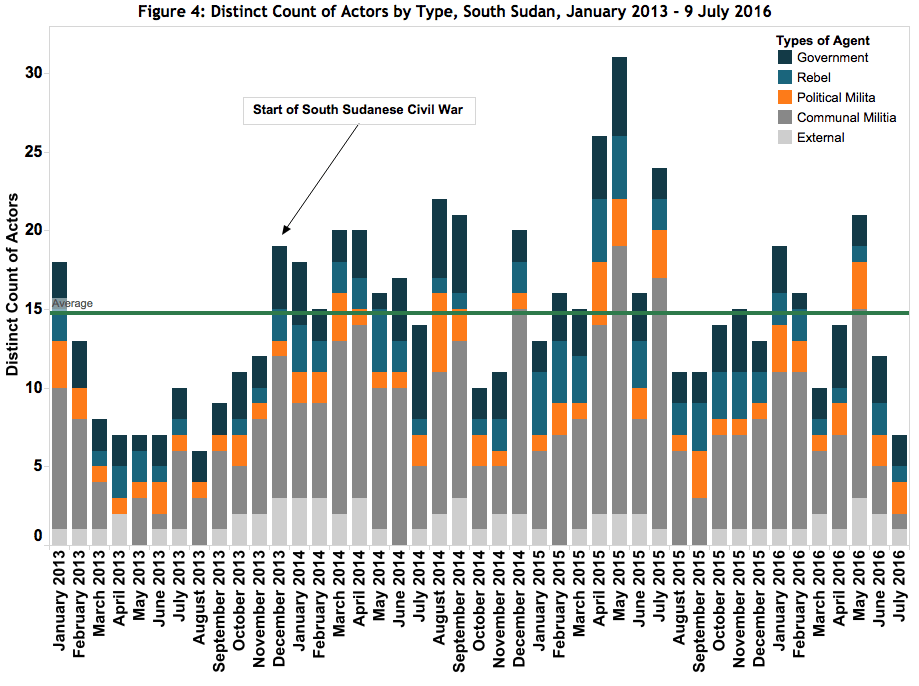

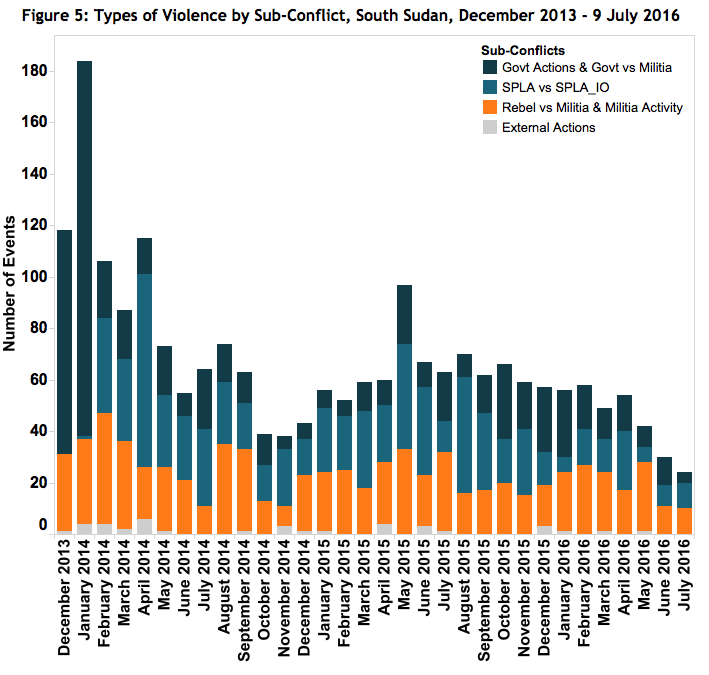

The various rates of activity by type of agent, and the increasing role of communal militias, are detailed in Figure 4. Ethnic and communal militias outside of Juba continue to fight through cattle raiding and revenge attacks. Jonglei state has the most battles involving ethnic and communal militias (due mainly to the Murle ethnic militia). Also, communal militias are involved in cattle raids and violence. Most unidentified communal militia activity over the past year takes place in Jonglei state.

The outcome of the Juba conflict will have serious ramifications for whose civilians are safest within that space, as well as for the losing party. Rumors about cracks in the government political elite (e.g. Malong splits from Kiir) will likely lead to a severe restriction in the formal SPLA forces, as they are dependent on the militias created and sustained by Malong. Further, new fronts (including Northern and Western Bahr El Ghazal) could open, as the conflict in Wau continues to increase. Should this pass, an agreement is likely between Kiir and Machar, and those communities allied with both.

Agents of Violence

While much of South Sudan’s activity involves the main two groups in opposition, a number of other political militias, and a plethora of communal militias (approximately 40) are also active. The South Sudan ‘relational’ space is best thought of as a national elite competition core, surrounded by a number of militias that operate both as local and supplemental troops for both core members (SPLA and SPLA-IO), surrounded by a much larger group of militias who operate solely within a communal, local space. Violence is significant from all of these violent agents.

The main opposition force is SPLA-IO, which is now technically part of the transitional government. Multiple offshoots of SPLA-IO that were angered when Machar reconciled with the Government (i.e. Gen. Peter Gadet) now exist. In 2015, the government promised an amnesty to rebels that disarm. Some did not want to disarm unless local forces first replaced Dinka elements of the army. In Yambio (Western Equatoria), the government signed a peace agreement with the South Sudan National Liberation Movement (SSNLM) in April 2016, after engaging in clashes with the military in January 2016.

In protest of Kiir’s 28 states decree, military defectors of the Shilluk ethnic group formed the Tiger Faction New Forces (TFNF) under the leadership of Yaones Okij in Manyo County (Upper Nile) (Radio Tamazuj, 3 October 2015). On 31 October 2015, TFNF held the Manyo County Commissioner hostage, claiming control of Wadakona as its headquarters. In November, the group clashed with military forces in Malakal. “The mobilization of armed young men highlights the peace deal’s limitations in addressing the deeply rooted grievances of smaller ethnic groups” (Al Jazeera, 21 November 2015).

In Eastern Equatoria, the South Sudan Armed Forces (SSAF), led by Anthony Ongwaja and consisting predominantly of Latuke ethnic group members, announced its arrival by taking control of a police station in Idolu in December. SSAF was also involved in battles in Longiro and Torit in Eastern Equatoria in December, in which 34 soldiers, police officers, and rebels were killed. Since December, SSAF has not reportedly been active.

Some of the most significant violence emanates from Dinka and Nuer militias, operating in and out of their home areas. South Sudan has had a long history of militarizing and training Dinka cattle herders, which are then partially or unofficially incorporated into government forces, leading to “hybrid domains of security” (Pendle, 2015). Prior to independence, Dinka youth often become de facto armed groups, comprised of young men protecting their land against raids committed by the Government of Sudan and by the White Army (the Nuer militia armed by Machar in the mid-1990s which would raid Dinka areas controlled by SPLA, at the time led by John Garang). Dinka militias such as Duk ku Beny received quasi support from SPLA forces, or at least tacit permission to become armed, in what was then Southern Sudan.

This tacit support effectively caused the Dinka militia in South Sudan to act similarly to the government-supported Janjaweed militia in Sudan. In other words, the presence of armed youth militias (whether Dinka in South Sudan, or Janjaweed in Sudan) is not simply a product of local disputes, but rather the effect of government forces arming cattle herders as a method of creating proxy fighters to ally against any existing opposition forces, as well as ensuring that new opposition is not created (by keeping local communities content and feeling able to defend themselves). Over time, the status of the Dinka militia may have changed (from informal to semi-formal and back again); however, their actions have remained essentially the same, except for violence being moved to new geographical spaces.

Disarmament campaigns amongst Dinka and other militias have been presented from the 2000s onward as an alternative to integration into armed forces. This has blurred the “government – home boundary” and altered limits of “legitimate violence” for communal militias that had become accustomed to being able to defend their lands through the acquisition of guns (Pendle, 2015). In order to remain legitimately armed, Dinka groups had to become increasingly (but still only partially) government-affiliated. Some armed groups were transformed into ‘community police’, eventually becoming Mathiang Anyoor. This group fought alongside Kiir against the SPLM-IO, further blurring the lines between ‘community police’ and soldiers. The integration of the Dinka militia into government forces or the transformation of Dinka groups into ‘community police’ has also left the impression that the GoSS has favored Dinka over ‘illegitimately’ armed Nuer groups, such as the White Army. The groups such as Mathiang Anyoor are believed to underscore the newest violence in the state.

The full version of trends in South Sudan can be found here.

Authors: Clionadh Raleigh and Roudabeh Kishi.