ETwelve months after the beginning of the uprisings in the Oromia region, violence shows no sign of decreasing in Ethiopia. In its strenuous efforts to contain a wave of protest unseen for decades, the government has launched a violent crackdown that is estimated to have killed more than one thousand people over one year. Thousands of people, including prominent opposition leaders and journalists, have been arrested and are currently held in detention centres across the country.

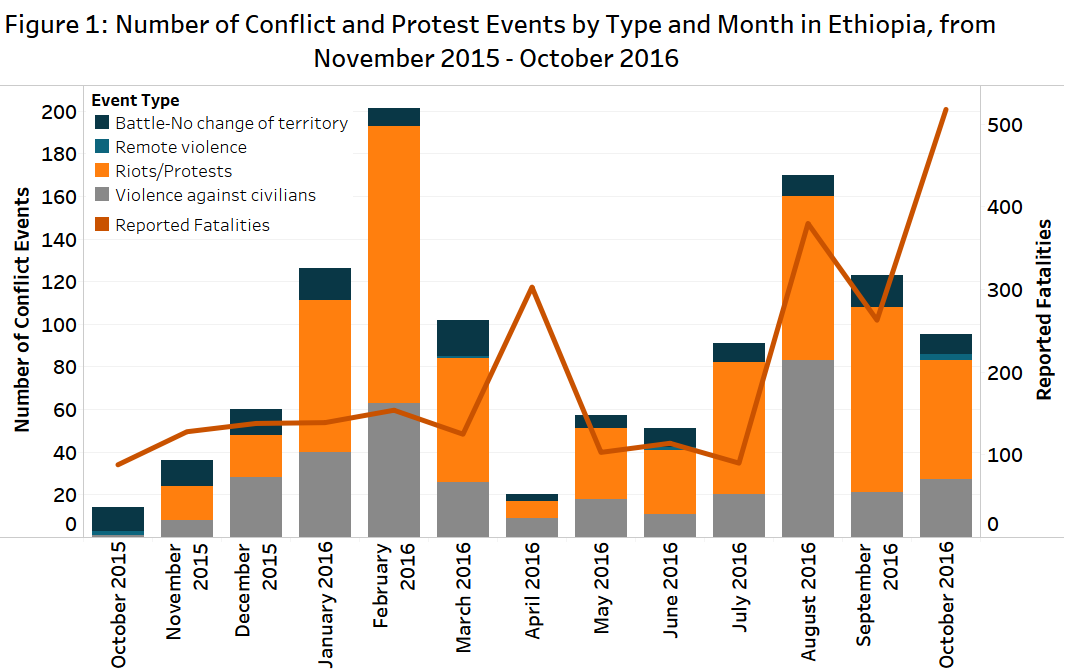

The month of October has seen the highest number of fatalities, with more than five hundred people reported killed despite decreasing overall levels of conflict (see Figure 1). Violence has flared up after the events at a religious festival in Bishoftu, when a stampede caused by police firing on a protesting crowd killed at least 55 people (Al Jazeera, 6 October 2016). The massacre was greeted with widespread outrage by the opposition, which blamed the government for the killings. In the following days, rioters vandalised and torched several foreign-owned factories and flower farms, accused of profiting from the government’s contested development agenda. An American biologist has also died when her vehicle was pelted with stones near Addis Ababa. Reports vary as to whether the rioters were locals or not.

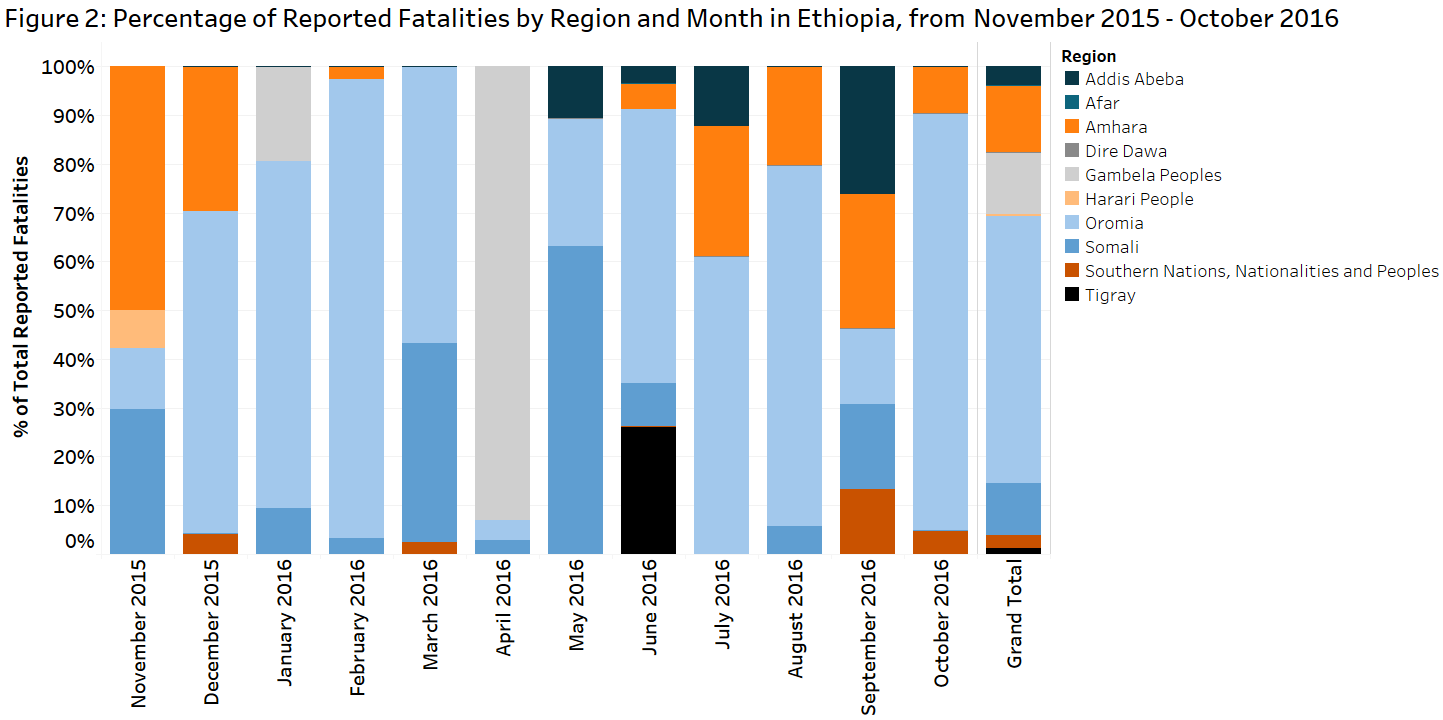

Additionally, data show how the unrest is evolving geographically across the Ethiopian territory (see Figure 2). Whilst the vast majority of the protests remain located in Oromia, where the local population first mobilised to oppose a government-backed developmental plan last November, other regions have increasingly experienced violence during the past few months (ACLED Crisis Blog, 9 September 2016). The Amhara region has witnessed more protests since mid-July, when discontent with state repression countrywide ignited pre-existing tensions over regionalist grievances around the city of Gondar (Africa Confidential, 22 July 2016). State crackdown on dissent was also reported in the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’, the native region of Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn, as local communities began to stage anti-government demonstrations (Association for Human Rights in Ethiopia, 20 September 2016).

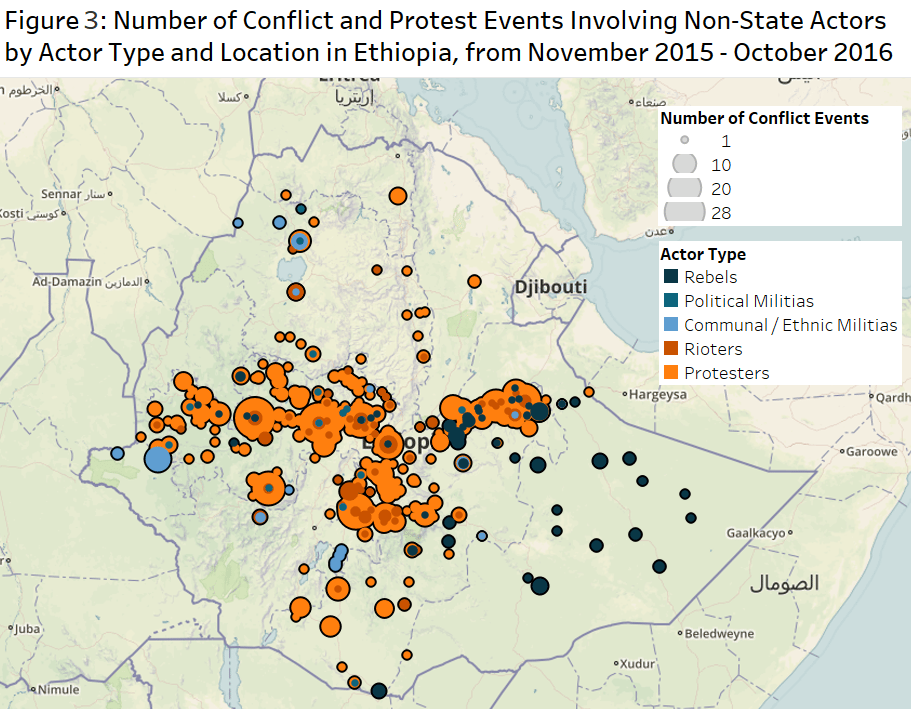

These trends seem to reflect the increasing lethality of state repression, which is contributing to escalating and diffuse conflict, rather than stifling dissent. Although most of the protests have remained peaceful over the past year (see Figure 3), the increasing incidence of violent riots and the emergence of local armed militias may point to an escalating conflict cycle. As indiscriminate repression continues, an increasing number of protesters may resort to violent tactics, turning the largely peaceful unrest into an armed insurgency. The risk of that occurring seems largely to be determined by government actions.

Despite these escalating trends, the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front coalition (EPRDF) is unwilling to mitigate its repressive measures. Internet access was allegedly shut down in the attempt of hampering the protest movement, which use online media and social networks to disseminate anti-government information and coordinate collective action. On 9 October, the government introduced a six-month state of emergency, the first time since the ruling EPRDF came to power in 1991 (Al Jazeera, 17 October 2016). Foreign diplomats were banned from travelling outside the capital Addis Ababa, a restriction that was lifted only on November 8 (BBC, 8 November 2016). At least 1,600 people are reported to have been detained since the state of emergency was declared, while the Addis Standard, a newspaper critical of the government, was forced to stop publications due to the new restrictions on the press (Nazret, 25 October 2016).

International institutions and non-governmental organisations have expressed major concerns on the deteriorating human rights situation in the country. In a joint statement addressed to the UN Human Rights Council, fifteen civil society organisations have called for “international, independent, thorough, impartial and transparent investigations” over the ongoing repression in Ethiopia (Human Rights Watch, 8 September 2016). The government has claimed that any allegations of systematic wrongdoings by its security forces are unsubstantiated, and has instead blamed “foreign elements” linked with the Egyptian and the Eritrean political establishments for instigating the rebellion and arming the opposition (BBC, 10 October 2016).

Following increasing pressure from the international community and foreign investors, the government has agreed to make some limited concessions to the opposition. After meeting with German Chancellor Angela Merkel, Hailemariam pledged to reform Ethiopia’s electoral system, which currently allows the EPRDF to control 500 of the 547 seats in Parliament (Newsweek, 12 October 2016). The leadership of the Oromo People’s Democratic Organisation (OPDO), junior ally in the ruling EPRDF coalition, was removed during the September party congress in a timid attempt to placate the protesters. On 1 November, Ethiopia’s Prime Minister reshuffled its cabinet, replacing some of the most unpopular ministers and assigning Oromos the key ministries of foreign affairs and communication (Financial Times, 1 November 2016; Nazret, 1 November 2016).

These limited concessions are nevertheless unlikely to deter the protesters. By contrast, they are widely seen as being orchestrated by the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), which has dominated the country’s political, economic and security elites since the EPRDF took power in 1991. Although some party hardliners have dismissed the opposition’s allegations of Tigrayan dominance as mere racism (Africa Confidential, 21 October 2016), the TPLF seems to recognise the need of a more accommodating stance towards the opposition. However, these decisions may have come too late to satisfy the protesters’ demand for immediate and substantial change.

Twenty-five years of uninterrupted EPRDF rule have left many Ethiopians discontent with rampant corruption, a political system increasingly perceived as unjust and the unequal gains of economic development. The protests have thus revealed the weakness of the social contract regulating Ethiopia’s political life since 1991, and call on Ethiopian elites to deliver far-reaching political reforms. However, the violent repression of peaceful protests is unlikely to ease the tensions the country has been experiencing since last year.