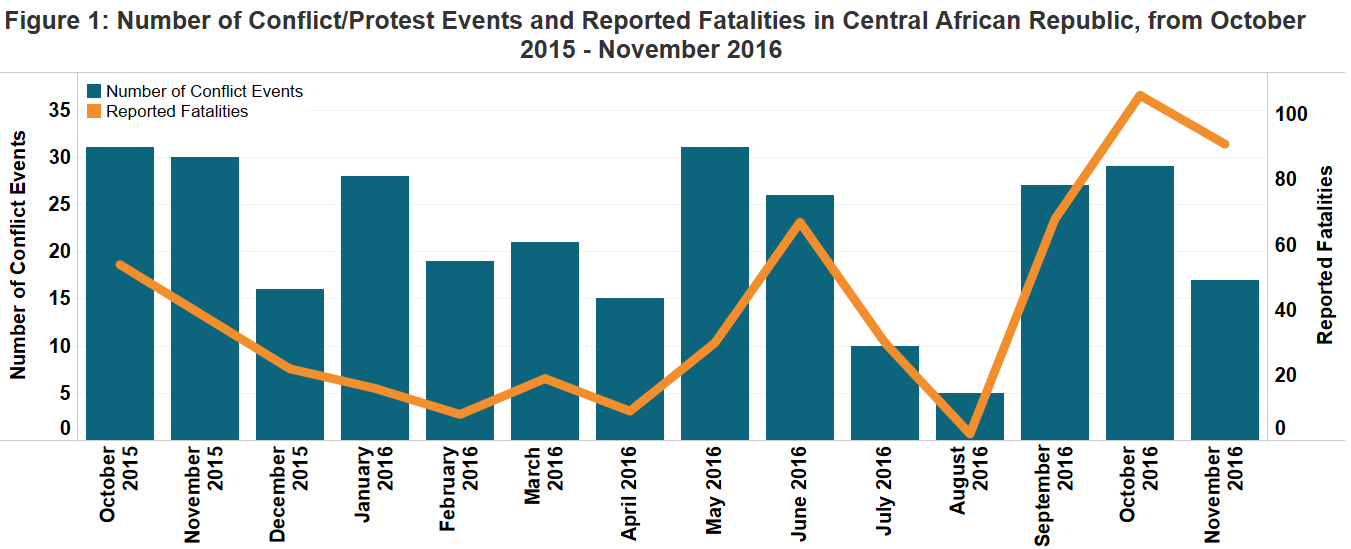

The Central African Republic witnessed an encouraging overall decrease in lethal political violence during the first half of 2016. However, this was followed by a dramatic jump in violence from September to November which stems from the failure of the new regime in Bangui to forge a political settlement that appeals to the increasingly fractured Seleka coalition and other militia groups (see Figure 1).

The electoral period, spanning from late December 2015 to March 2016, saw a general decrease in the number of violent events, albeit with spikes. There was a high incidence of political violence during the lead up to the second round of elections in January, largely due to police repression and protest within Bangui and activity by the Lord’s Resistance Army and communal militias on the periphery of the country. The main belligerents of CAR’s political crisis– the Seleka coalition and the Anti-Balaka militia– remained comparatively inactive (Africa Confidential, 22 January 2016). The election itself, though marred by irregularities concerning ballot boxes and the absence of a reliable register, was accepted internationally and Faustin-Archange Touadera was announced as the winner (ibid.).

Touadera, a former premier during the Bozize years, constructed a government composed of former ministers and colleagues from the Bozize era unknown outside of Bangui (Africa Confidential, 10 June 2016). More importantly, the cabinet did not include any senior representatives from either Anti-Balaka or the various Seleka factions, who expected a power-sharing agreement and positions within the cabinet as a reward for keeping the peace during the polls (ibid.).

In the aftermath of the announcement of the cabinet in May, violence involving Anti-Balaka and Seleka actors dramatically increased as militia commanders became aware that they would not secure their livelihoods within the new government in Bangui. As a result, groups within Seleka such as the FDPC (Democratic Front for the People of the Central African Republic) and UPC (Union for Peace in the Central African Republic) began to settle into provinces to assert their control over the local people and resources.

In spite of the surge in violence in June, July and August were the most peaceful months of 2016. This may be due to DDR (disarmament, demobilisation and social reintegration) talks between the government and the armed factions ongoing during the summer (Agence France Presse, 1 August 2016). Though the armed groups had failed to gain representation in the government, the DDR process represented an opportunity for fighters to gain a livelihood within a new integrated national army. The DDR process reached a stalemate after the government opposed Seleka’s desire to join the army. Unable to find a compromise, hardline ex-Seleka factions chose not to take part in the latest DDR discussions (International Crisis Group, 16 November 2016). Similarly, jobs in the army and police promised to Anti-Balaka were cancelled due to pressure from international partners (Africa Confidential, 21 October 2016).

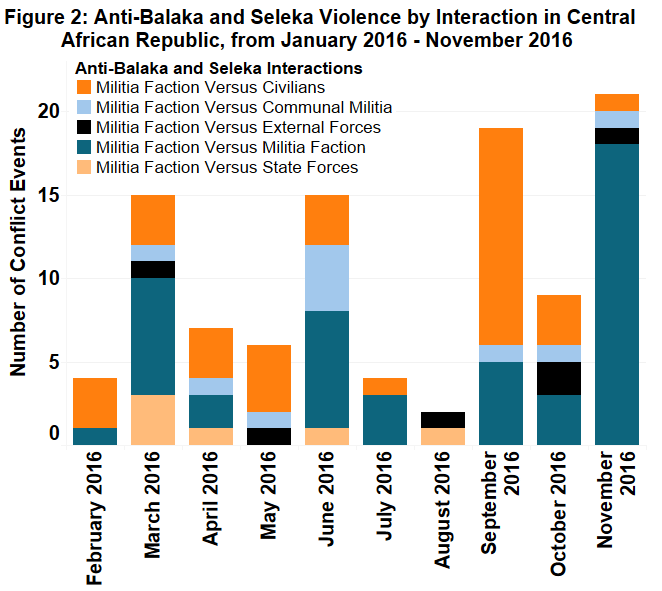

With the Seleka factions unable to find any place for themselves in the new government, violence increased during the latter third of the year with October, September and November represented the three most lethal months of the year so far. Unable to secure resources through central government patronage, militias resorted to establishing control of local resources and extorting the local population. Seleka groups also banned all government administration from areas they control (International Crisis Group, 16 November 2016). Exactions against the population by Seleka led to retaliatory attacks by Anti-Balaka. In the resulting cycles of retaliation civilians bore the brunt of the violence (see Figure 2).

By November a new dynamic emerged in which different groups that constitute the Seleka coalition fought over territory and control of local human and mineral resources. The most violent of these clashes is the ongoing battle between the UPC and the Popular Front for the Renaissance of Central Africa (FPRC) in Bria. The two groups are currently fighting control over the taxes levied on nomadic Fulani herdsmen during the seasonal cattle migration and diamond mines (Human Rights Watch, 5 December 2016). Similar clashes, although fewer in number and smaller in magnitude, occurred between groups of Anti-Balaka over the ownership of cattle.

The localisation of these conflicts means that the rise in violence in the latter third of the year is confined to the hinterlands far from Bangui. This geographic distribution of conflict has the ability of the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) and the severely limited government security forces to control the violence. Clashes between the militias and state or external forces have remained low even as violence against civilians and between militia groups has risen (see Figure 2).

MINUSCA itself is facing a legitimacy crisis in the aftermath of numerous findings of extra-judicial killings and sexual assaults against the population. Distrust of the main peacekeeping forces resulted in violence in October when civil society groups in the capital protested against MINUSCA’s presence in the country. In the resulting violence, four people died (International Crisis Group, 16 November 2016).

Meanwhile, Touadera’s focus seems to be on eliminating potential political threats in Bangui. Jean-Francis Bozizé, son of former leader Francoise Bozize, is currently in Bangui and attempting to resurrect his father’s political party Kwa Na Kwa (KNK) (Africa Confidential, 2 December 2016). Francoise Bozize supported Touadera’s rival during the elections, current opposition figure Anicet-Georges Dologuele, and many KNK voters who supported Touadera feel that they have not been rewarded by the president (ibid.). Compounding Touadera’s focus on Bangui is the persistent insecurity within the restless PK5 neighbourhood which was the scene of clashes between local militias and also the assassination of the head of security for former Interim President Catherine Samba-Panza (Africa Confidential, 21 October 2016).

The dramatic increase in conflict during the latter part of the year and the concentration of violence in the hinterlands, far from the reach of an administration focussed on establishing security in the capital, represents an ominous trend after a hopeful start to the year.