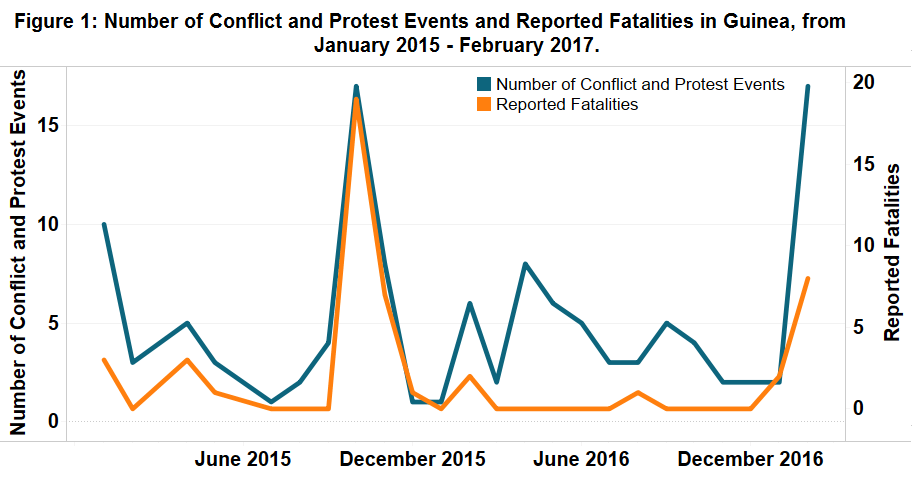

In February, Guinea witnessed the highest levels of political violence and protest since the presidential elections in October 2015 (see Figure 1). Over the past month, Guinea suffered a nationwide strike which spiralled into violence leaving eight people dead, infrastructure destroyed and left the capital city, Conakry, paralysed. The strike was incited by Guinea’s main teacher’s union on February 1st after a government decision to dismiss and cut the salaries of many junior teachers (Al Jazeera, 20 February 2017). As the strike progressed, more unions joined and teachers demanded a pay rise of 7.5-10.3%, and a resumption of work for contracted teachers. Pupils of the striking teachers demonstrated in the streets in a show of solidarity and demanded the resignation of the Minister of Education (Al Jazeera, 20 February 2017; Philipps, 27 February 2017).

The most violent episode occurred after the unions and the government had formed an agreement over pay. On February 19th, both sides agreed to delegate salary decisions to a technical commission at the end of March (Philipps, 27 February 2017). The following day, clashes between demonstrators and police claimed seven lives, demonstrating a divide between the union leadership and grassroots. To further placate the rioters, President Alpha Conde fired his education minister, along with the civil service and environment ministers, and appointed a former teacher and union activity to the education portfolio (Agence France Presse, 28 February).

Strikes have a precedent of enforcing political change in Guinea. In January 2007, the United Trade Union of Guinean Workers (USTG) called a strike and demanded the resignation of then President Lasana Conte (Global Nonviolent Action Database). This strike was related to Conte’s decision to pardon two prominent businessmen convicted of corruption. In spite of mass state violence resulting in the deaths of over 50 protesters, continued strikes forced Conte to appoint a new Prime Minister to the vacant post. When the initial nominee was deemed too close to Conte, pressure from unions and protesters forced the president to choose a new prime minister from a list approved by union leaders.

Given the union’s past successes in forcing the hands of the state, it is understandable that union-led strikes can organise political demands across ethnic and regional divides. This would explain why the protests in Conakry touched neighbourhoods that have typically avoided protests and sided with the government (Philipps, 27 February 2017). Nevertheless, the recent strikes, though much lower in fatalities, indicate a worrying separation between the demonstrators on the street and the union leadership negotiating with the government, with some leaders distancing themselves from the destructive acts of the rioters. For the moment, the protests have calmed but the widening divide between representative and protester may hamper the effectiveness of union strikes in the future.