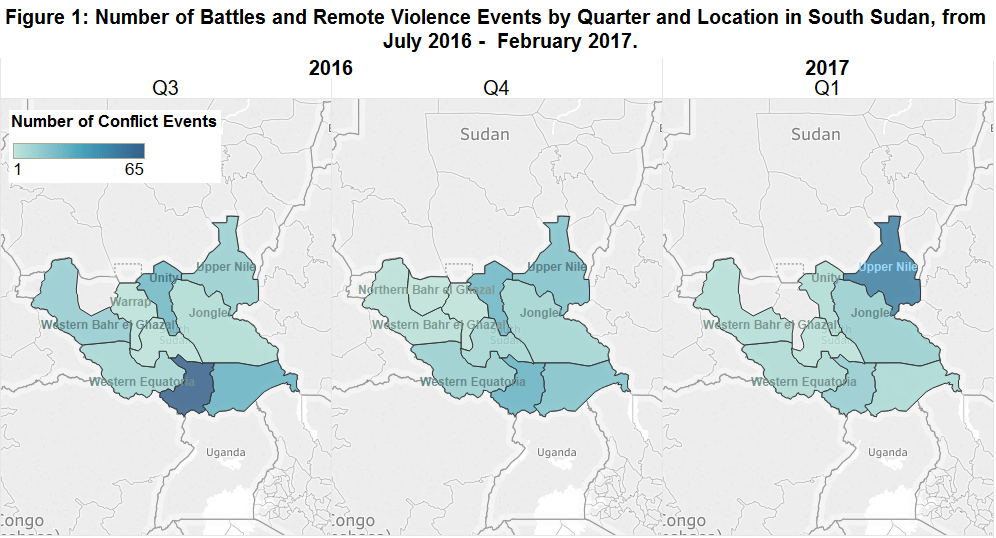

Higher levels of violence have rocked South Sudan since July 2016, when battles re-erupted between the government and the rebel Sudan People’s Liberation Army – In Opposition (SPLA-IO) in the capital Juba. Between July and October, the spread of the conflict remained localized in Greater Equatoria (ACLED, November 2016), but since November, this trend has shifted, with violence instead regaining grounds in other parts of the country, particularly in Upper Nile, Unity and Jonglei states. These shifts are due to continued insurgencies against the regime of president Salva Kiir and inter-communal fighting.

Rebellion

Government and SPLA-IO forces have fought in all South Sudanese states since November (see Figure 1). Despite the reported mobilization of additional militias and troops to support government offensives in Greater Equatoria (HRC, 14 December 2016), violence in the region has reduced by half since November. Notwithstanding, heavy battles were reported through to February, with SPLA-IO forces claiming to have gained a number of territories in Yei, Morobo and Magwi counties (Radio Tamazuj, 2 December 2016; Sudan Tribune, 2 October 2016), and insecurity persisting in Yambio and Kajo-Keji (Radio Tamazuj, 22 January 2017; Radio Tamazuj, 10 November 2016).

In parallel, battles occurred in Upper Nile, Unity and Jonglei, all long standing sites of rebellion. But the recent trends mark a return to the onset patterns of the civil war in 2013. In oil-rich Upper Nile state, government forces sought to recapture a number of strategic positions along the Nile from SPLA-IO, notably in Nasir (Radio Tamazuj, 9 January 2017), and areas in and around Malakal, where violence flashpoints have appeared between Dinka and Shilluk communities since the division of states by president Kiir in 2015 (UNMISS, 16 February 2017; Radio Tamazuj, 26 January 2017; ISS, 12 January 2017). In Unity, movement of SPLA-IO forces led by Taban Deng Gai to the north during mid-November led to clashes with Machar’s SPLA-IO forces in Rubkona’s Nhialdiu, creating fear and destabilization in the area. Machar forces lost control of Dablual in Mayendit county to SPLA at the end of November (Protection Cluster, February 2017). Fighting significantly subsided until February, when a man-made famine occurred in two Unity counties, prompting president Kiir to announce major offensives to remove SPLA-IO forces (Sudan Tribune, 4 March 2017). Finally, conflict between government and opposition forces has flared up in Jonglei since February, when SPLA dislodged the White Army (allied to Machar) from its base in Yuai and subsequently clashed with SPLA-IO forces in various other areas (Radio Tamazuj, 17 February 2017; Radio Tamazuj, 1 March 2017).

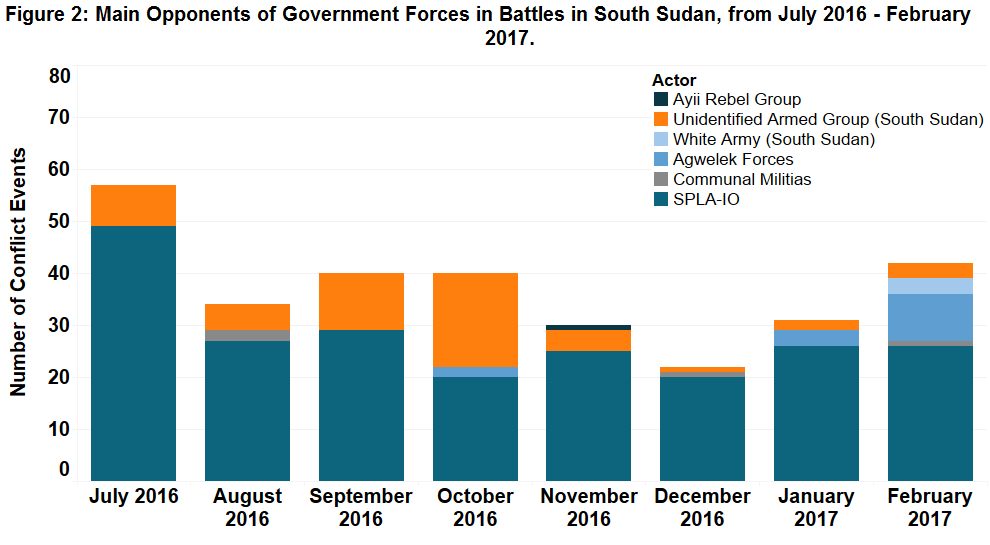

Battles since November have hinted at the level of support each side receives from allied forces. Agwelek, as well as White Army militias, fought government forces in their respective areas (i.e. in Upper Nile and Jonglei), reaffirming their support to Machar’s opposition movement. Battles between unknown armed groups and government forces reduced, which might signify a consolidation of Machar’s support base (see Figure 2). Government forces, for their part, are supported by Dinka militias, including the Mathiang Anyoor, which attacked SPLA-IO in Central and Eastern Equatoria in February and March (Sudan Tribune, 5 March 2017), and allegedly by Sudanese rebels and Egyptian forces in recent battles in Upper Nile, which, if verified, could cause significant regional destabilization (SSNA, 3 February 2017).

Developments, however, also revealed the fragility of each front. The absence of a strong and unified opposition movement to the regime can be seen in clashes between Machar forces and Lam Akol’s National Democratic Movement (NDM) on several occasions in Upper Nile, as well as in the many reported defections from Machar’s movement to the government or to NDM, and the creation of new rebellions and parties, most recently the New Salvation Front (Radio Tamazuj, January 2017; Sudan Tribune, 6 March 2017). On the other hand, resignations by dozens of senior SPLA and government officials; defections of hundreds of SPLA soldiers between December and February criticizing the government’s failure to implement the August 2015 peace deal; and accusations of government crimes, corruption and ethnic bias, show a lack of support for president Kiir’s policies and the regime’s tackling of the current crisis (Xinhua, February 2017; Sudan Tribune, 2 December 2016). Kiir’s dismissal of a number of officials demonstrating a lack of support for his policies or any link with the Machar opposition (such as the Imatong State Governor in Eastern Equatoria in February), has led to clashes and underlines Kiir’s own lack of interest in a sustainable resolution of the conflict (Radio Tamazuj, 10 February 2017).

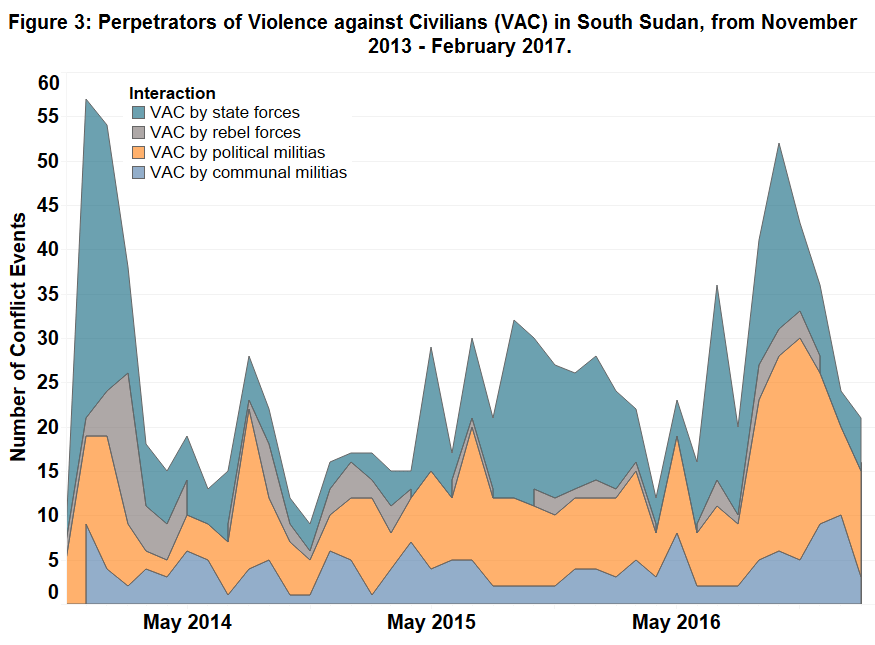

Divisive policies by president Kiir carry the potential to further spread dissidence across the country, notably along ethnic lines as resentment grows against Dinka domination. Violence against non-Dinka civilians by state forces –and the culture of impunity surrounding these acts– reinforces grievances towards those forces meant to protect populations. While state violence against civilians decreased since October, incidents of killing, rape, abduction, looting and property destruction have continued, particularly in areas where clashes with the opposition occurred. This points to an unceasing crackdown on dissent. SPLA forces were reportedly responsible for 18 cases of killings, torture, rape and beatings following clashes in Western Equatoria between December 2016 and January 2017, for instance (Commission on Human Rights, 6 March 2017). More recently, at the end of February, SPLA forces also allegedly arrested and killed a group of 31 civilians accused of supporting the opposition following clashes in Jonglei’s Canal state (Radio Tamazuj, 2 March 2017). In reaction, armed attacks against Dinka civilians by unknown groups have proliferated (see Figure 3), particularly along roads in Equatoria, where Machar is said to have built a strong support base. Because many of these armed groups are local and their military arrangements informal, they are not included in security arrangements or peace dialogues – which could ultimately derail the implementation of any peace agreement in South Sudan (ISS, 12 January 2017).

Inter-communal violence

Between October 2016 and January 2017, corresponding to the beginning of the dry season, there was also an increase in violence by communal and ethnic militias in Jonglei, Lakes and Bahr el Ghazal states, mainly in the context of armed cattle raids or revenge killings (see Figure 3). While cattle raiding is widespread in South Sudan, these areas are particular violence flashpoints since the division of states by president Kiir in 2015, which exacerbated ethnic conflict and hardened the positions of communities that previously shared resources (ISS, 12 January 2017). In Jonglei for instance, Murle tribesmen have been responsible for the killing and abduction of dozens of civilians from the Dinka tribe in armed cattle raids across Pochalla, Bor, Twic East and Uror counties. Despite the two tribes reaching a peace agreement in December, criminality persists (Africans Press, 20 December 2016; Sudan Tribune, 7 March 2017). In Bahr el Ghazal in January, Tonj state herders repeatedly attacked farmers and communities of Jur River county and near Wau town over a cattle dispute. Over five days at the end of January, they reportedly killed 22 civilians and burnt down houses in or around Wath-lelo, Atido and Maleng areas of Jur River County, forcing thousands of people to flee to Wau town (Sudan Tribune, 1 February 2017).