Conflict levels reduced by nearly half between April and May 2017 in South Sudan. This is mainly due to reduced battles between the two main opposing factions, the government and rebel Sudan People’s Liberation Army-In Opposition (SPLA-IO), as well as to lower civilian targeting. This is a repeated occurrence at the onset of the rainy season, with expectations that conflict will likely resume later in the year close to November, barring peace negotiations.

Battles continued between government and rebel forces in May, though at reduced levels and with a different geographic focus. While Upper Nile remained an important battleground – SPLA-IO and Agwelek forces claimed to have recaptured Tonga after heavy offensives early May for instance – fighting in Jonglei and Western Bahr El Ghazal significantly subdued compared to April (Sudan Tribune, 4 May 2017). Government and rebel forces instead clashed around Panyjiar in Unity, and around rebel positions along the border with the Democratic Republic of Congo in the southern part of Central Equatoria (mainly around Yei and Kajo-Keji) (Radio Tamazuj, 26 May 2017).

The reduction in battles can be attributed to the onset of the rainy season in May, which makes conflict logistics and ease of movement more difficult. The downward trend might also be linked to conflict resolution efforts undertaken at the national level. These include president Salva Kiir’s dismissal of the controversial army chief of staff, Gen. Paul Malong, whom several senior army officers accused, upon resigning from their positions, of conducting an ethnic war against non-Dinkas (Al Jazeera, 9 May 2017); and the announcement, in parallel to the launch of the delayed national dialogue process on 22 May, of a unilateral ceasefire and pardon (Radio Tamazuj, 1 June 2017).

However, the continuation of the government’s counterinsurgency campaign throughout May – including via the deployment of additional troops in strategic rebel areas (Sudan Tribune, 9 May 2017) – and the conditioning of SPLA-IO’s participation in the national dialogue to the side-lining of their leader, Riek Machar, compromised the government’s credibility in regards to these efforts. SPLA-IO refused to participate in the national dialogue and continued its offensives as a result, which could significantly affect the relevance of the overall dialogue process.

Communal violence also reduced in May across South Sudan. This can be attributed to reconciliation efforts between rival communities. In Central Equatoria for instance, the Dinka and Mundari tribesmen agreed to cease fire following a series of attacks on civilians in Terekeka state (Gurtong, 22 May 2017). In Lakes, members of the Gony tribe clashed with various communities, but reconciled with the Thuyic. Finally, in Jonglei, the Dinka Bor and Murle reached a ceasefire agreement on 23 May, following weeks of negotiations amid unceasing revenge attacks and cattle raids (Radio Tamazuj, 25 May 2017).

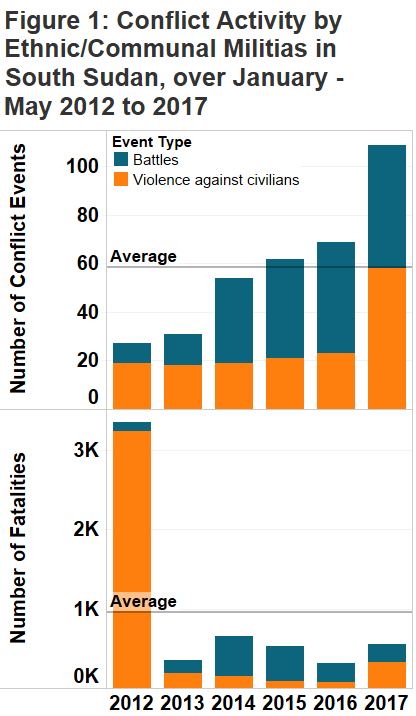

It is important to note, however, that intercommunal infighting reached unprecedented levels in the first part of 2017 in South Sudan. Over January – May 2017, there were nearly 1.5 times more conflict events involving communal/ethnic militias than over the corresponding period in 2016, which had already represented a peak in South Sudan’s history. There was also a marked rise in civilian targeting in the context of this violence (see Figure 1). These South Sudanese militias are now among the most active on the whole African continent.