While many studies of political gender-based violence (GBV) have focused on the practices of groups during wars, the practices of gendered repression in unstable—but not warring—developing states is under-acknowledged and ought to be scrutinized equally closely. There has been significant research on GBV within developing states, and investigations typically concern the pervasiveness and embeddedness of GBV within the social sphere (i.e. domestic circumstances and society) or crisis situations, including civil wars. To date, a comprehensive exploration of GBV as political violence outside of domestic circumstances, yet within the public political sphere, and outside of the specific context of wartime, is missing.

Political violence against women—or gendered repression—is a denial of specific forms of security for women within unstable settings, and it remains poorly documented. It is a practice wherein women are targeted by political agents (e.g. police, military, militias, local authorities, customary authorities) in an effort to enforce a political order. The motives for this violence are to create a high-risk political space; to humiliate and oppress women; to prevent the effective participation of women within the political scene, especially in efforts to sustain women’s rights and empowerment; and to generally perpetuate an environment of high instability with violent consequences. While sexual violence strategies can be used as a terror tactic to cultivate an environment of fear, gendered repression is more systematic and widespread across a society and can include other targeting tactics to carry out political violence against women as well, in addition to sexual violence strategies.

Widespread and persistent rates of political violence that do not necessarily escalate into large crisis or civil war situations are common across developing and low-income states across the African continent, and the use of gendered repression to thwart the political participation of women is not unusual. While exploring GBV within conflict settings solely during times of full-scale civil war may capture a large proportion of sexual violence, a number of cases are systematically left out, disallowing analysis to capture the full spectrum of GBV on the ground within these contexts.

The Gendered Repression Dataset, which draws on ACLED data, will be the first dataset to explore the impact of political violence on women and the gendered responses to political activism women face at the local to national scales, while not limited solely to civil war periods.

There are a number of examples of cases where political violence is common yet the situation has not necessarily escalated into ‘civil war’ (i.e. where a rebel group is trying to overthrow the government). One such example is Zimbabwe, where the use of gendered repression to thwart the political participation of women is not unusual.

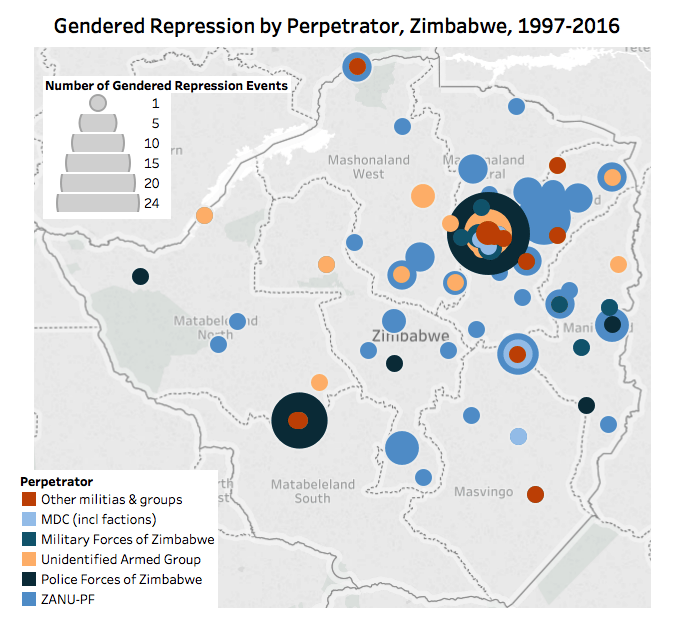

Figure 1 below depicts preliminary findings from Zimbabwe where gendered repression events are mapped. It is evident that state forces, such as police and the state military, are primarily active in urban areas, such as Harare and Bulawayo. Meanwhile, non-state groups, such as ZANU-PF and the MDC (including their various factions) seem to be more active and spread their activity across larger spaces. This may be a result of using gendered repression as a strategy during elections when political parties are seeking votes or re-election.

While the dataset is not yet finalized for release, preliminary findings suggest that this tactic has been increasing at a rapid rate in recent years in Africa, and that political militias—or ‘armed gangs’ operating on behalf of political elites—are the primary instigators of this type of violence. Additionally, this type of violence seems to be especially prevalent during contentious contexts, such as election periods.

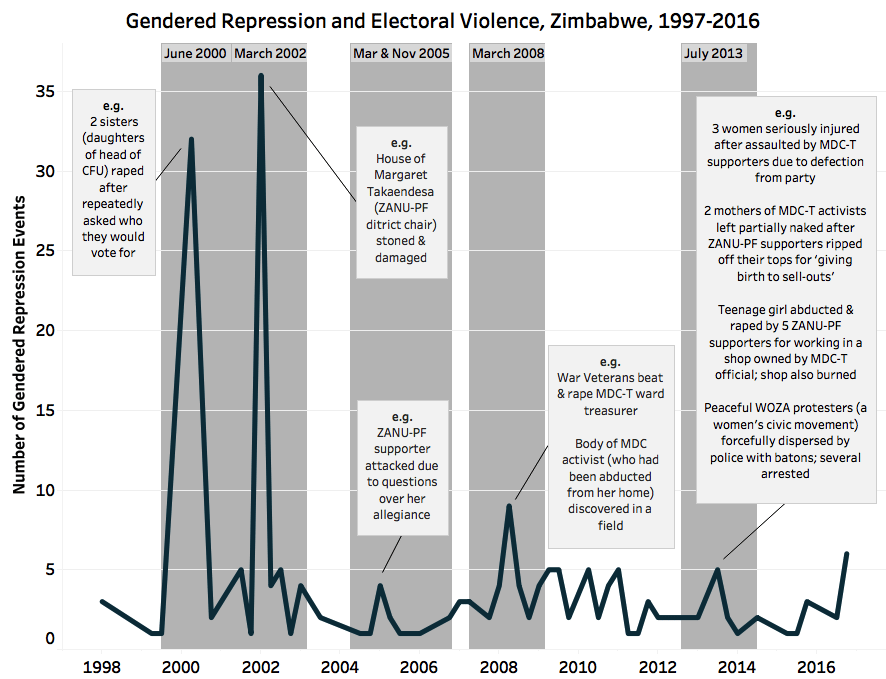

Figure 2 below depicts the use of gendered repression in Zimbabwe with election periods highlighted; this is the 25-month period that includes the 12 months before an election, the election month, and the 12 months following an election. The spikes in activity suggest that gendered repression is a conscious strategy used to thwart women’s political participation during these times. Some example events have been annotated on the graph, where women have been raped, attacked, abducted, and even killed in conjunction with who they support; where female political leaders have been targeted; where women’s bodies have been used as weapons of humiliation; and where peaceful protests for women’s right have been forcefully put down.

This highlights how, despite the fact that a country might not be categorized as ‘during war’, women still face gendered violence within the political sphere aimed at limiting their political participation through an array of gendered responses that go beyond solely sexual violence. Identifying when and where women may be most at risk of this type of violence is a crucial step toward fostering environments in which women can be active contributors to political processes.