Somalia continues to be the most conflict-affected country in Africa in 2017 with 1,537 organized violent events. By comparison, South Sudan is the second most violent state, with 686 organized violent events thus far this year. Somalia has also incurred the most reported fatalities thus far this year (3,287 reported fatalities). While battles continue to result in the most reported fatalities (56% of all reported fatalities this year), the proportion of reported fatalities stemming from battles has decreased in recent years. But reported fatalities stemming from both remote violence as well as violence against civilians have both increased during this time – with Al Shabaab being the primary perpetrator of both of these types of violence.

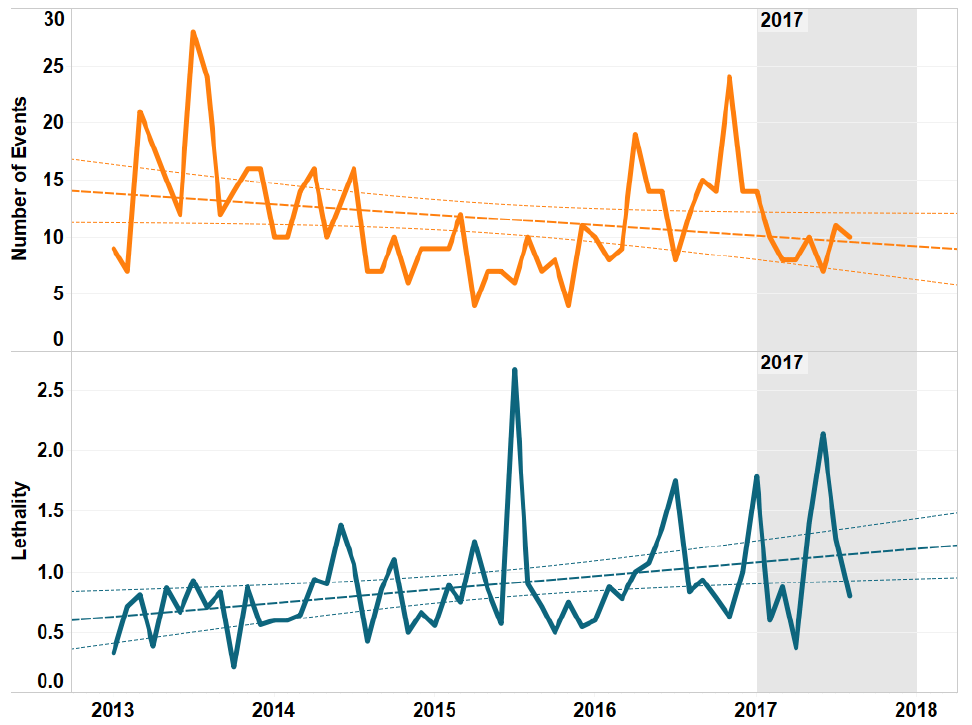

The lethality of violence (number of reported fatalities per conflict event) against civilians has been on the rise since 2013. While Al Shabaab of Somalia falls high on the list of most lethal conflict actors against civilians in Somalia, they do not top the list. A number of clan militias – specifically, the Habar Gedir Clan Militia, Jejele Clan Militia, and Darood-Marehan Sub-Clan Militia – have been more lethal toward civilians this year, meaning that more civilians are reportedly killed as a result of each of their attacks. While the rate of violence against civilians carried out by clan militias has remained relatively constant over time, the lethality of this violence has been increasing (see Figure 1).

While large, high-profile actors such as Al Shabaab remain responsible for both high absolute levels of political violence, and a significant share of anti-civilian violence, strategically, the rate and lethality of events involving Al Shabaab have both remained relatively constant.

Meanwhile, the lethality of violence by diverse clan militias has been on the rise, attesting to the sustained security risk and threat to civilian vulnerability that they constitute. In fact, the majority of new conflict actors in Somalia during the past year are clan militias, active in a variety of areas.

Unidentified armed groups (UAGs) also continue to be very active in Somalia. Thus far this year they have been second only to Al Shabaab. UAGs’ activity against civilians, including remote violence against civilians, is particularly high. It is very likely that UAGs may be carrying out violence on behalf of others, such as Al Shabaab (Kishi, 9 April 2015).

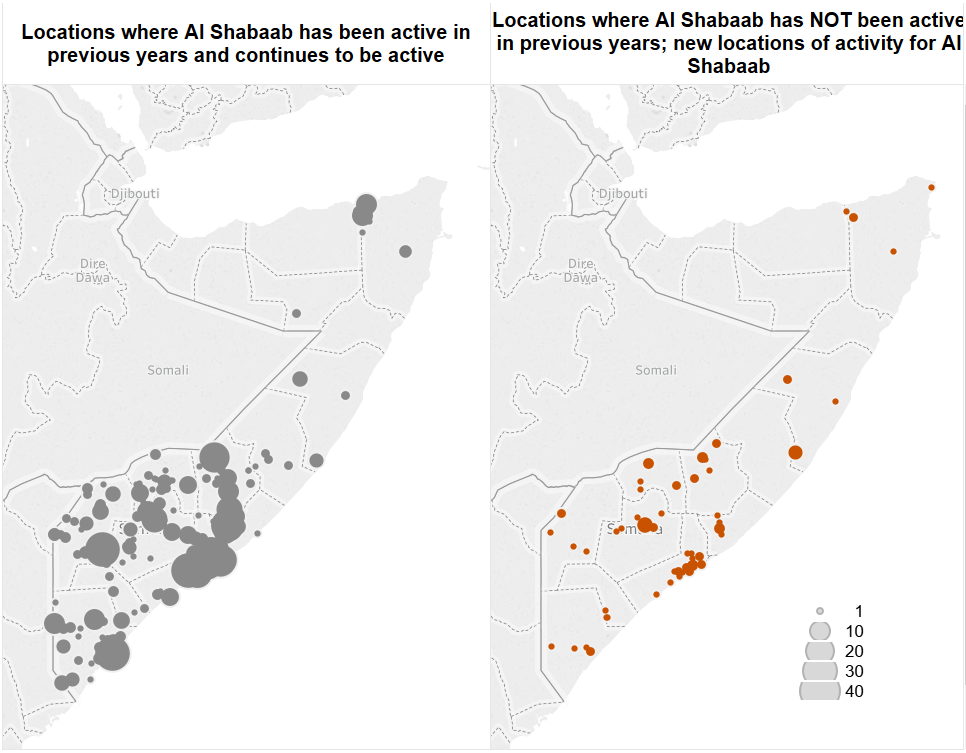

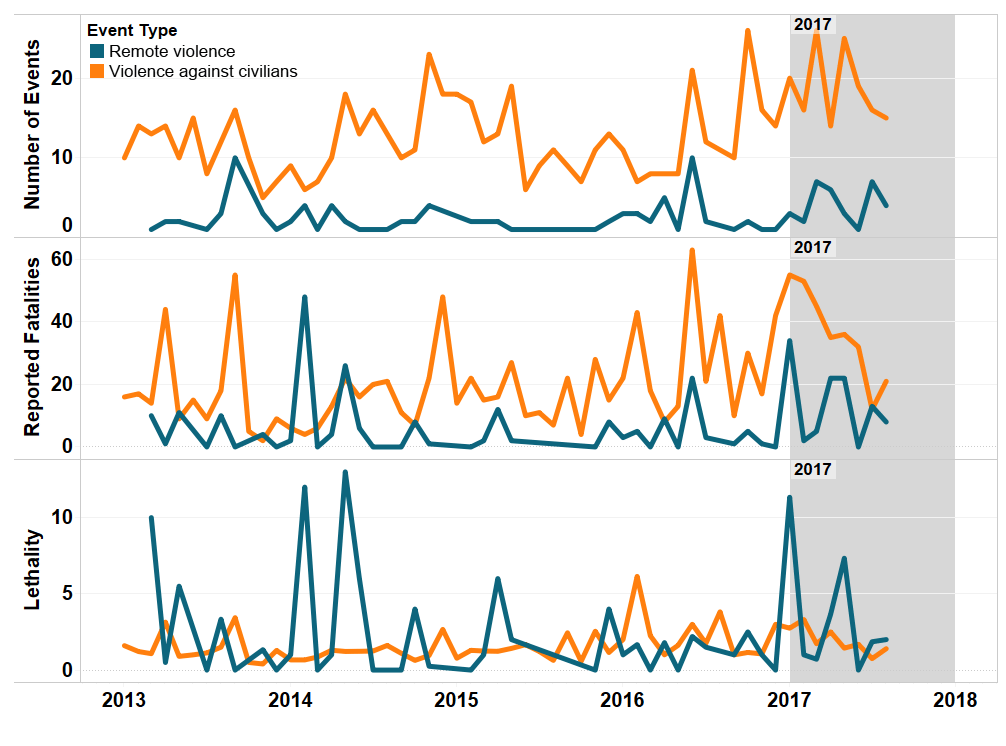

But Al Shabaab have been responsible for the most reported civilian fatalities. Remote violence carried out by Al Shabaab against civilians this year – especially violence involving IEDs – has increased the number of reported fatalities (see Figure 2). This could point to a shift in strategic tactics by the group.

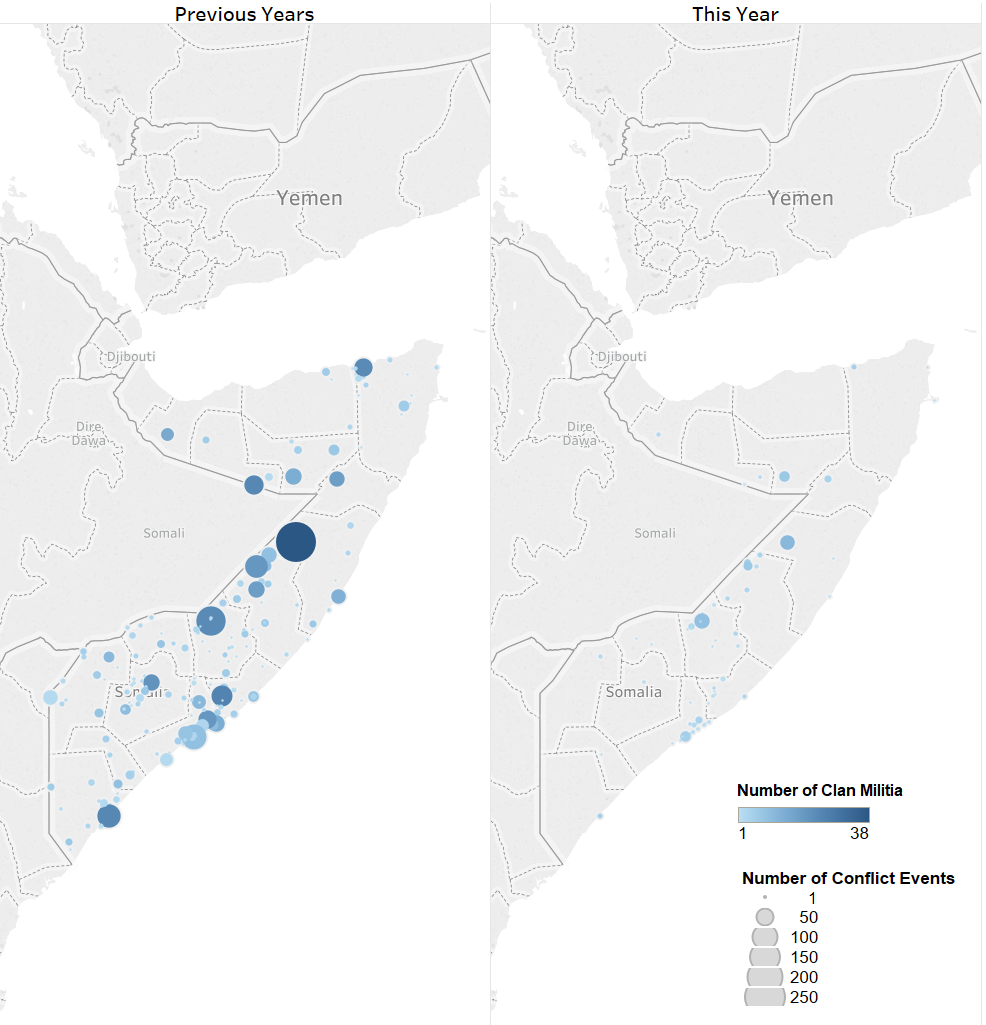

This is coupled with Al Shabaab’s continued geographic expansion into new locations, including a number of new locations in Shabeellaha Hoose (see Figure 3), putting more civilians at greater risk. As Al Shabaab expands into new locations, the number of clan militias active in those same locales is impacted. This suggests a relationship between clan militias and Al Shabaab — namely that Al Shabaab may in fact be a ‘brand’ under which numerous clan militias may fight. This is not to say that there is no centralized Al Shabaab; in fact, Al Shabaab has indeed been successful in usurping groups, as can be seen when clan militia activity has stopped in certain locations into which Al Shabaab has recently expanded (see Figure 4).

Figure 2: Anti-Civilian Violence Rates, Reported Fatalities, and Lethality Involving Al Shabaab in Somalia, from 2013 – 2017

Specifically, when looking at the locations in which Al Shabaab is newly active this year, the number of distinct, active clan militias has decreased in many of these locations during this same time.

Recently, a series of high-level Al Shabaab defections have been reported (Somali Update, 13 August 2017), with many defectors living in Mogadishu while enjoying state protection. This blanket protection “[does] little to deter future atrocities while simultaneously undermining reconciliation efforts” (Ismail, 31 August 2017). These defections could suggest that the group may be splintering. Some have pointed to this possibility, noting increased mistrust among its members leading to the emergence of splinter cells – some swearing allegiance to ISIS while others remaining affiliated to Al Qaeda (Wabala, 13 August 2017). Alternatively, there may be a change coming in Al Shabaab’s campaign tactics or direction. Some suggest this could be in the form of a renewal of ties with the Yemen-based al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) (Meservey, 3 January 2017). In any case, Al Shabaab continues with two defining features: opportunism and deadly activity. The conflict landscape in Somalia is changing as a result of changes within Al Shabaab and the activity of clan militias and their alliances with non-state actors.