The presence of pro-government militias during civil wars has been a prominent feature in armed conflicts across the globe, and Syria is no exception (Kishi and Raleigh, 2018). The Syrian government first mobilised loyalist gangs, known as “Shabiha,” to act against civilian opposition when peaceful demonstrations began in Syria in 2011 (Marsh and Siddique, 2011). Later on, the army has relied on various militias, both local and foreign, for ground support during battles (Ezzi, 2017).

As earlier ACLED analysis suggests, these pro-government militias play a wide variety of roles in Syria. Questions remain about how often are these militias leading battles without the involvement of the Syrian Army? How much flexibility do these militias have to determine their scope of actions? What insights about the future disarmament and disbandment of these militias do event data provide?

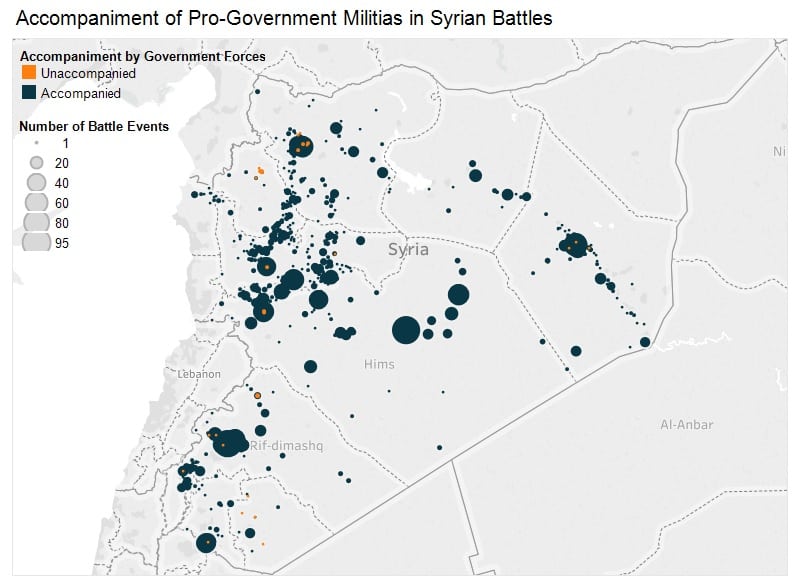

Based on analysis of internal ACLED data, pro-government militias were accompanied by the Syrian Army in 99% of all events in which they took part across 2017 and 2018. Pro-government militia involvement in Syrian conflict events appears to be highly embedded within the Syrian Army during battles and suggests a mutual dependence or a possible lack of trust.

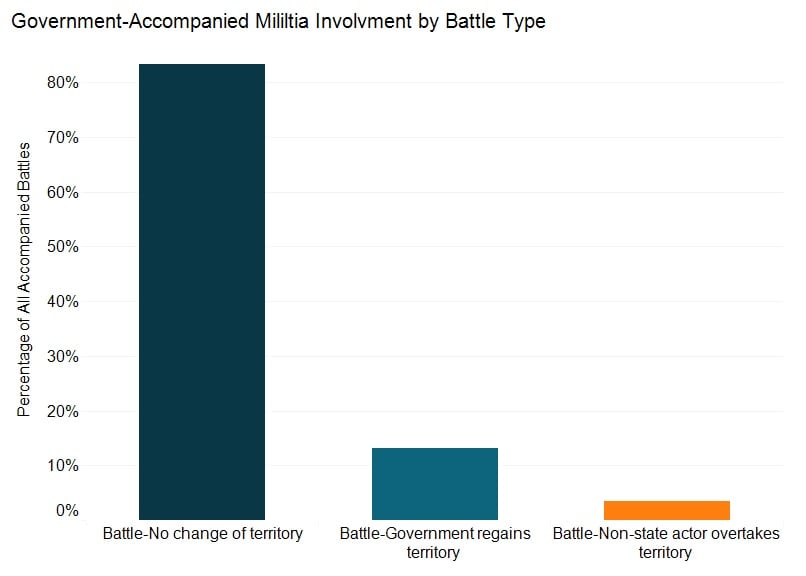

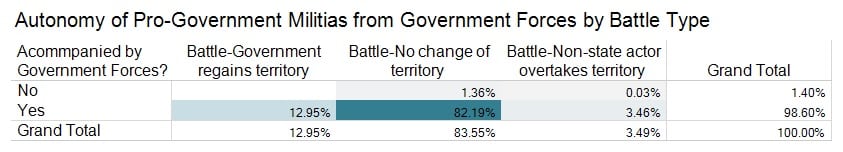

They engaged mainly in battles where no territory was exchanged; when pro-government militias were accompanied by regime forces, only 12.95% of those battles resulted in territorial takeovers. Out of the few unaccompanied events, these militias showed an extremely low frequency of territorial takeovers (0.03%), instead playing a more defensive role and suggesting that attacks were likely initiated against their positions by other armed actors (see figure and table below).

Generally, pro-government militias do not demonstrate the degree of flexibility and autonomy that is implied by a popular conception of them. Since Hezbollah became a crucial government ally by raising a Shi’ite flag after gaining control of Al-Qusayr, Homs following battles in 2013 (AAP, 2013), the belief that militias can lead offensives is a common trope.

Conflict literature suggests that governments often rely on militias to deflect accountability for atrocities, hold local areas for control by indirect alliances or serve as a mode of competition for elites within regimes (Kishi and Raleigh, 2018) and possibly to retain legitimacy in the eyes of the international community (Aliyev, 2018). Simultaneously, governments tend to balance the power given to militias to avoid future challenges to the state (ibid). Looking back to the initial use of “shabiha” gangs to suppress protest and carry out violence against civilians, it appears that the government mobilised militias to deflect accountability in the period before the opposition became militarized (Kishi and Raleigh, 2018).

However, as the army later struggled to cope with its manpower issues (Lister and Nelson, 2017), its reliance on militias could be a way of keeping potential armed and trained groups close to the regime. They could pose a far greater challenge to the state in a post-victory scenario.

It is unclear whether future disbandment and disarmament of these militias is to occur post-conflict. However, disbanding defensive pro-government militias, such as the National Defense Forces (NDF), will likely pose a challenge given their localized character that has branded them as “new centers of authority and local powerbrokers” in Syria (Zambelis, 2017).