A particularly pressing question for policy-makers is the form and intensity of violence to expect from IS now that it lost its control of Raqqa, Deir-ez-Zor and Al-Bukamal. Since the defeat in Al-Bukamal (November 2017), IS has split into various groups. One group moved to Idleb where it created havoc for the early months of 2018 before it being defeated by regime forces. Next to this is a group of IS fighters in Yarmouk Camp (Damascus) and some scattered forces in Hasakeh district (North-East).

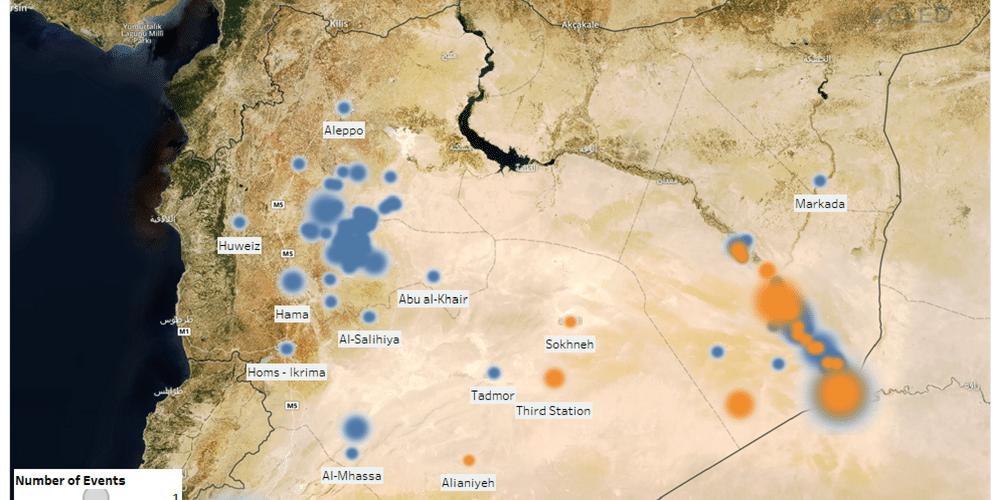

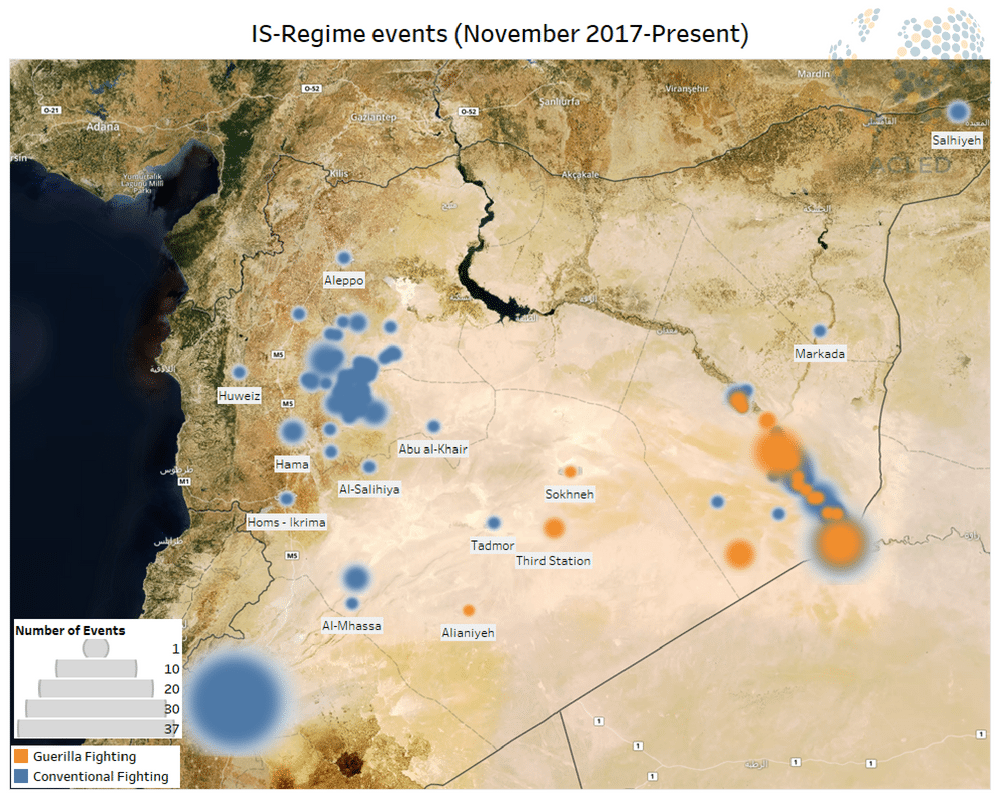

Yet the majority of IS fighters are split by the Euphrate with one group (in the east) holding up near the Iraqi border area (and fighting the SDF and Coalition) and another IS group on the west side of the Euphrate fighting the Regime. This last group of Islamic State (IS) fighters is currently ´based´ in the area of “Al-Badiya”, an area of the Syria desert. ACLED data show that the transition from populated areas to the desert has led this group of IS fighters to adopt a new mode of operation, effectively trading a strategy of territorial control for a a guerilla strategy fought in the desert.

IS ‘Al-Badiya’ group guerilla strategy in the desert

IS forces fighting the regime in Al-Badiya desert are organized in small independent and well-trained groups of fighters who engage in hit and run guerilla strategy. IS has continuously attacked Syrian army positions along the western bank of the Euphrates river, and far eastern countryside of Homs (e.g. the pumping station near Tadmor “Palmyra” and the strategic city of Sokhneh). The strategy may stem from its leaders from Afghanistan with AQ and Taliban and former members of the Iraqi army.

The group relies on two main tactics for carrying out its guerilla strategy in the desert. The first tactic involves ambushing at road-intersections used by the Syrian army and its allied militias to move between Syria’s south and east. An example of this tactic, occurred on the 23rd of May, when IS fighters attacked a convoy of the Syrian army, NDF forces and Hezbollah in Al-Mayadeen desert and arrested more than 80 fighters. The goal of the first tactic is to restrict any movement of the Syrian army and its allies on roads near IS presence as well as to cater for supplies. The second tactic in the IS desert guerilla strategy involves ‘sneak attacks’, whereby IS fighters use the desert as camouflage. Most of these attacks start with a detonation (IED) or car bomb (an element of surprise) and are followed up with an actual attack. IS tends to stage this second tactic often simultaneously at a number of places requiring it to use more forces and equipment to cover a relatively small area.

The regime’s response and the future

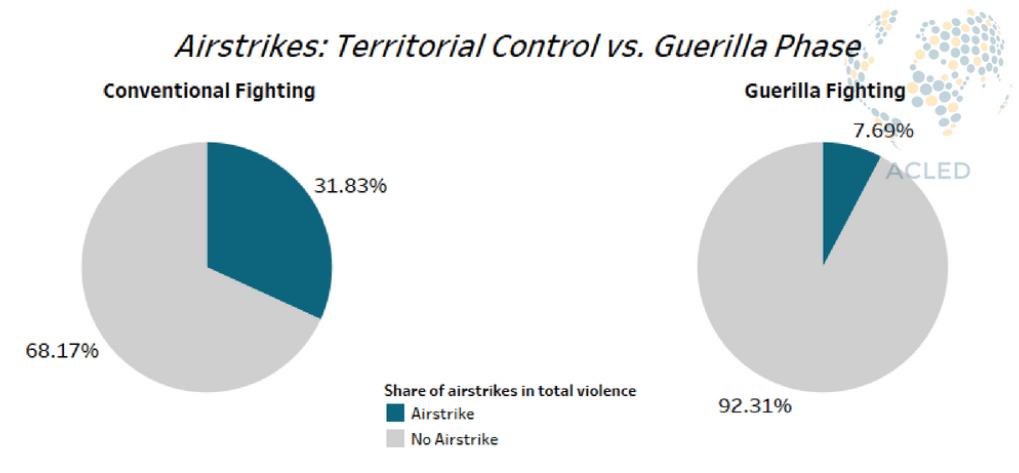

The Syrian regime replaced Iraqi and Afghani Shiite militias with elite forces of Hezbollah’s “Al-Rida division” and tribal forces who have civilian support as a result of the IS desert guerilla strategy. Yet, the regime is also facing inherent limitations as it cannot use its air dominance against IS’ guerilla strategy. IS’ hit and run tactics do not allow the regime time to exploit its dominance in the air. ACLED data show that the participation of the regime or Russian air forces has been rare with air support only accounting for around 8% compared to 32% in pre-November 2017 attacks (see figure 2).

The regime has not yet found an answer to the new mode of IS operation, but the prospects of coming up with a proper reply are somewhat unfavourable. The agreement with IS when the regime closed in on Yarmouk camp has brought IS fighters from the south of Damascus towards the group in Al-Badiya desert letting IS grow in strength and being harder to handle. The groups long term goal to link up with the other IS presence on the West of the Euphrate may therefore become one step closer. And this means, unfortunately, that the problem will not only be the regime’s to solve but may become a problem for the coalition and its associated forces based on the East of the Euphrate as well.