The Muslim populations of South Asia observed the holy month of Ramadan this year with bids for peace in two of its most volatile areas: Afghanistan and Jammu & Kashmir (J&K). In both places, governments sought a temporary cessation of hostilities by announcing unilateral ceasefires against militant groups. However, the outcomes of the ceasefire strategies varied, with the experimental peace in Afghanistan meeting more success than its parallel in J&K. The 2018 Ramadan ceasefire in Afghanistan was more successful than that in J&K because of the shorter timeframe, buy-in from militants, and the historical and organizational legitimacy of the Taliban compared to separatist groups in J&K.

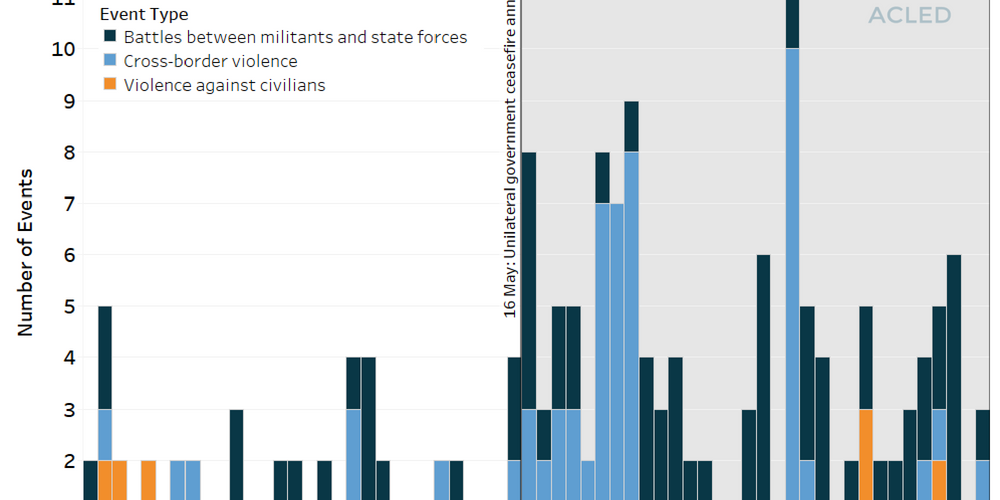

In J&K, the central government’s ceasefire against all militants lasted one month and was not reciprocated by the other parties. This had the effect of allowing organizations like Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM) and Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) to move in essence freely for an entire month — not limited in their ability to carry out attacks against government forces. In fact, militants capitalized on the situation and ramped up their campaign against government forces after the ceasefire announcement on 16 May, as Figure 1 below depicts. Militant groups also continued to kidnap, attack, and murder civilians throughout the state. Unarmed, off-duty policemen and a prominent editor have fallen victim to militant attacks recently.[1]

Afghanistan’s central government was slightly less ambitious, yet more realistic, in its announcement of a ceasefire of only seven days against only one group, the Taliban. In an unprecedented move, the Taliban reciprocated with a three-day truce over the weekend of Eid. These agreements were unprecedented in the war in Afghanistan that has lasted nearly two decades.

In addition, the nature of the militancy in J&K and Afghanistan are inherently different. The Taliban have a long history in Afghanistan and even controlled a majority of the country from 1996 to 2011. They are a relatively well-organized group of tens of thousands of members capable of strategy, bureaucracy, and politicking (NBC News, 30 January 2018). The Taliban’s goals include participating legitimately within the political framework and sovereign territory of the Afghan nation (for more on this, see this past ACLED piece). In contrast, militants in J&K are spread out among a number of smaller groups without any central command; most seek the separation of the Jammu & Kashmir state from India. The relationship between the militants and local populations in J&K is also unique; locals will often interfere in battles between government forces and militants on the side of the latter by pelting stones to distract and overwhelm state forces. The conflict dynamics in Afghanistan and J&K differ greatly, and these distinctions contributed to the difference in outcomes in the 2018 Ramadan ceasefires.

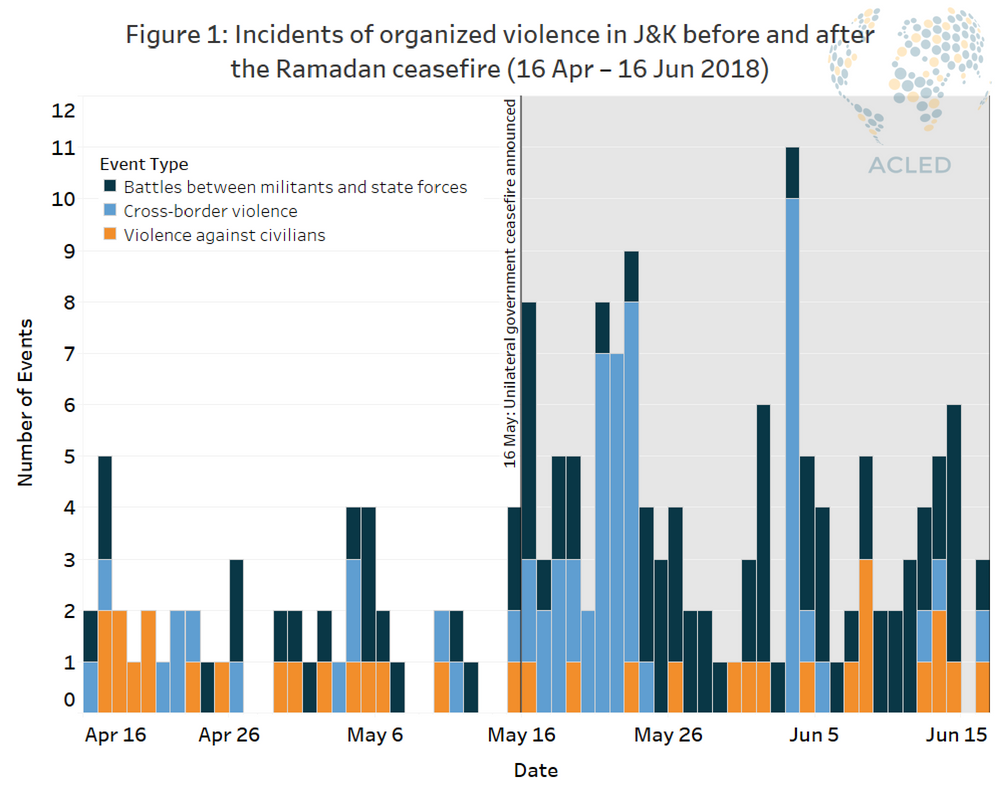

The shorter ceasefire in Afghanistan also allowed government forces and their NATO allies to focus their efforts on countering other groups operating in the country, including the Islamic State and Al Qaeda. Figure 2 below shows a noticeable decrease in engagement between state forces and all militants after the beginning of the government’s ceasefire. There was still a high level of violence between the Taliban and state forces on 12 June, the first day of the government ceasefire, as the Taliban had not begun its own unilateral ceasefire yet. However, the incidents between the two groups drop on the second and third day and disappear entirely once the Taliban ceasefire goes into effect. Additionally, the emphasis on countering groups other than the Taliban becomes clearer as the days progress. The assassination of the leader of the Pakistani Taliban (Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan, or TTP) in a US drone strike, for example, is considered a major victory for Afghan and foreign forces.

After a month of intense violence against civilians and battles between militants and government forces in J&K, the government called for an end to its unilateral ceasefire against militants. In contrast, the Afghan government extended its ceasefire with the Taliban before the initial time period was even over in a show of confidence. One of the strengths of the Afghan ceasefire may have been that it was a reciprocated, albeit unequal, agreement between the government and armed opposition. Additionally, holding a shorter “trial period” allowed for the sides to signal their intentions and gain some mutual trust. The differing outcomes of the two ceasefires in Afghanistan and J&K offers these valuable lessons for future peacemaking.

[1] During this same period, the military of India also twice met with and made agreements with its counterpart in Pakistan after particularly deadly rounds of cross-border firing. Around 36 fatalities were reported in the border areas due to cross-border violence during the month of 16 May – 16 June.

AnalysisAsiaCivilians At RiskEthnic MilitiasFocus On MilitiasJammu & KashmirPolitical StabilityPro-Government MilitiasRemote Violence