Since its formation in November 2014, the Yemeni branch of the Islamic State (IS) has undergone major changes in its organisation and tactics. Thanks to a more radical stance that has attracted several fighters from the Salafist movement and Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), the group has contributed to increasing sectarianism in Yemen. As of June 2018, however, only a few hundred armed militants are believed to be fighting for IS, which plays a marginal role in the current Yemeni conflict.

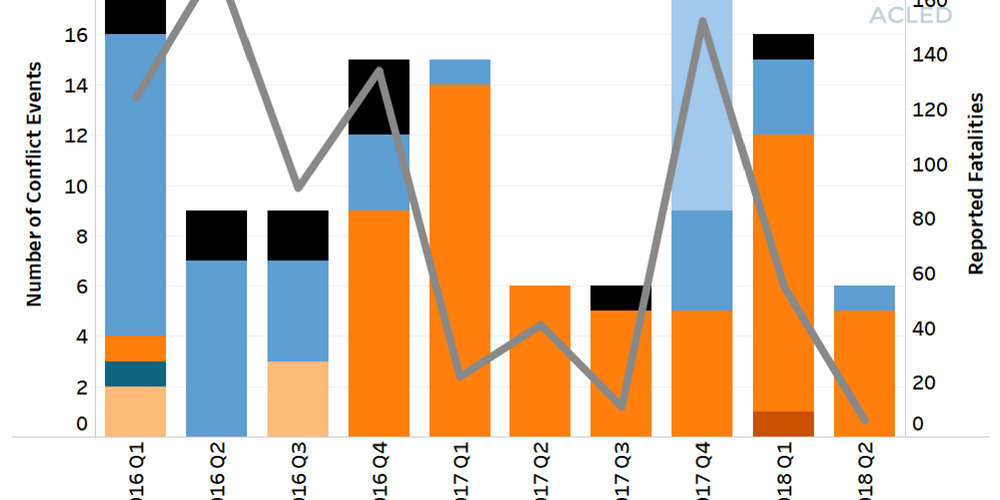

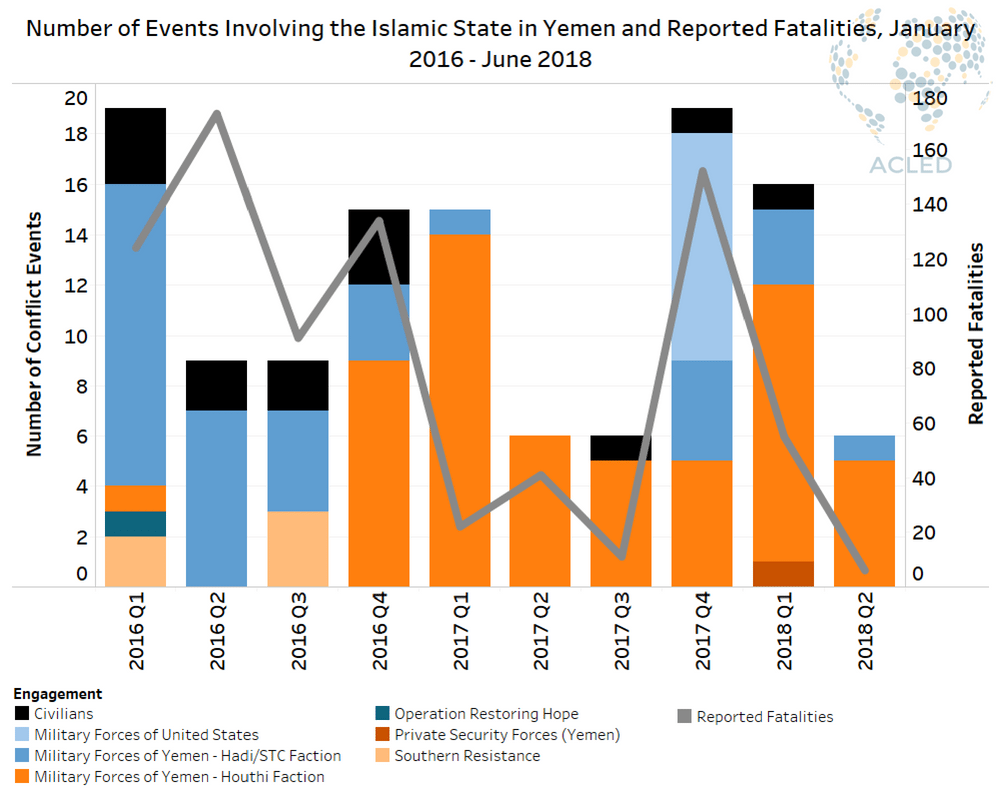

Over the past few months, IS’s activity has declined significantly. The total number of events involving the Islamic State last quarter was the lowest since 2017, while the number of reported fatalities in these events reached its nadir (see Figure 1, data available from January 2016 onwards). The number of actions claimed by IS has also diminished dramatically in 2018, pointing to a structural weakness that has affected its operational capacities.

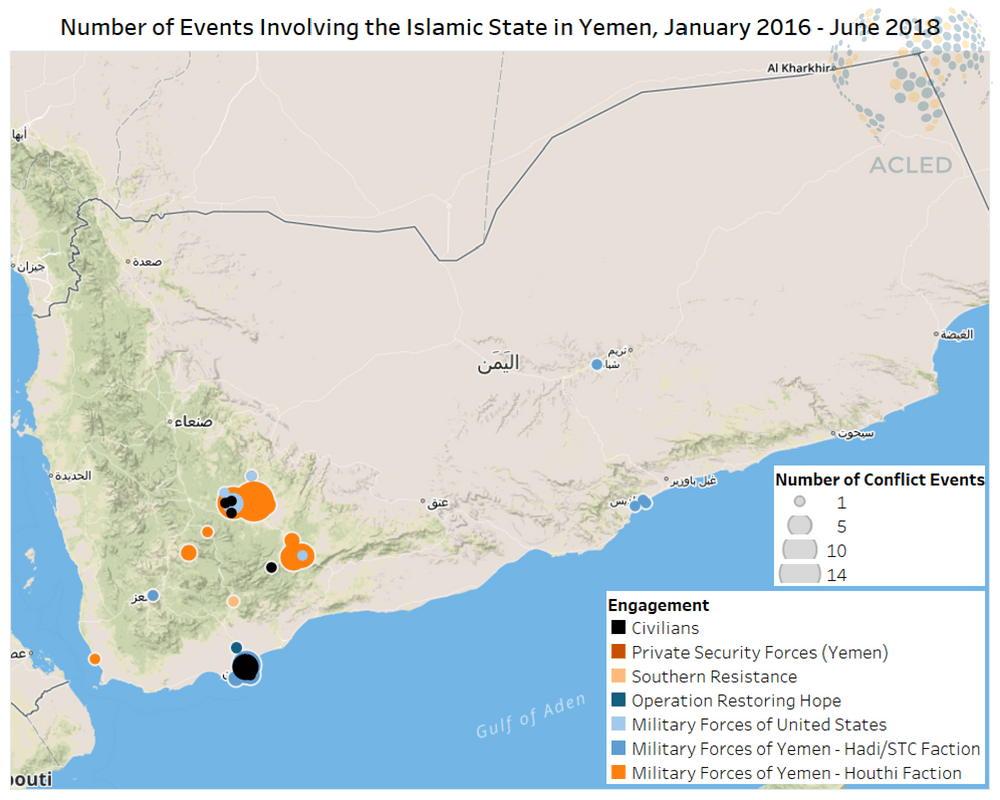

Since late 2016, IS has also redirected its activity increasingly against the Houthis, largely concentrating in the Al Bayda front where the Houthis are also fighting pro-government troops, local armed militias, and AQAP. While Al Bayda continues to constitute its main area of activity, the group has also recently been present in Ibb, northern Lahij and Aden (see Figure 2). In one of the most recent events, four IS suicide bombers attacked the headquarters of the UAE-backed Security Belt Forces in the At Tahawi district of Aden, reportedly killing fourteen people, including civilians. However, although Yemen’s second largest city has been the site of some of the deadliest bomb attacks carried out in the country in recent years, the number of armed events involving IS in Aden has plunged from 32 in 2016 to 6 in 2017 and 5 in the first six months of 2018.

This decline in the activity of IS in Yemen is the result of several factors. Internal divisions and the collapse of the self-declared caliphate in Syria and Iraq have hampered the group’s recruitment capacity, which have never managed to attract more than a few hundred fighters. Contrary to AQAP, which has often succeeded in securing the support of local tribes, IS has never been perceived as endemic to the local social fabric and has failed to establish territorial control in any areas the country. Despite its stronger sectarian rhetoric, IS has faced competition from AQAP and other Salafist movements, whose military and political successes have been more effective in attracting radical extremist fighters. Finally, counterterrorism campaigns conducted by UAE-funded military forces in southern Yemen (and by the United States with limited air strikes in late 2017) have contributed significantly to target IS’ leadership and to dismantle its militant cells.

Despite these major setbacks, IS has not ceased to exist in Yemen. It continues to operate alongside other pro-government militias against the Houthis capitalising on sectarian divisions, while waging sporadic attacks against government forces. In Al Bayda, IS and AQAP are believed to have a “tacit non-aggression pact” against their common enemy, thus suspending their mutual hostility. Currently a marginal actor, IS would thrive again should support for other Salafist actors dwindle and sectarianism remain a major fault line in the current conflict.

Find an explanation of ACLED’s methodology for monitoring the conflict in Yemen here.

AnalysisCivilians At RiskConflict MonitoringEthnic MilitiasFocus On MilitiasMiddle EastPolitical StabilityPro-Government MilitiasUnidentified Armed GroupsVigilante MilitiasViolence Against Civilians