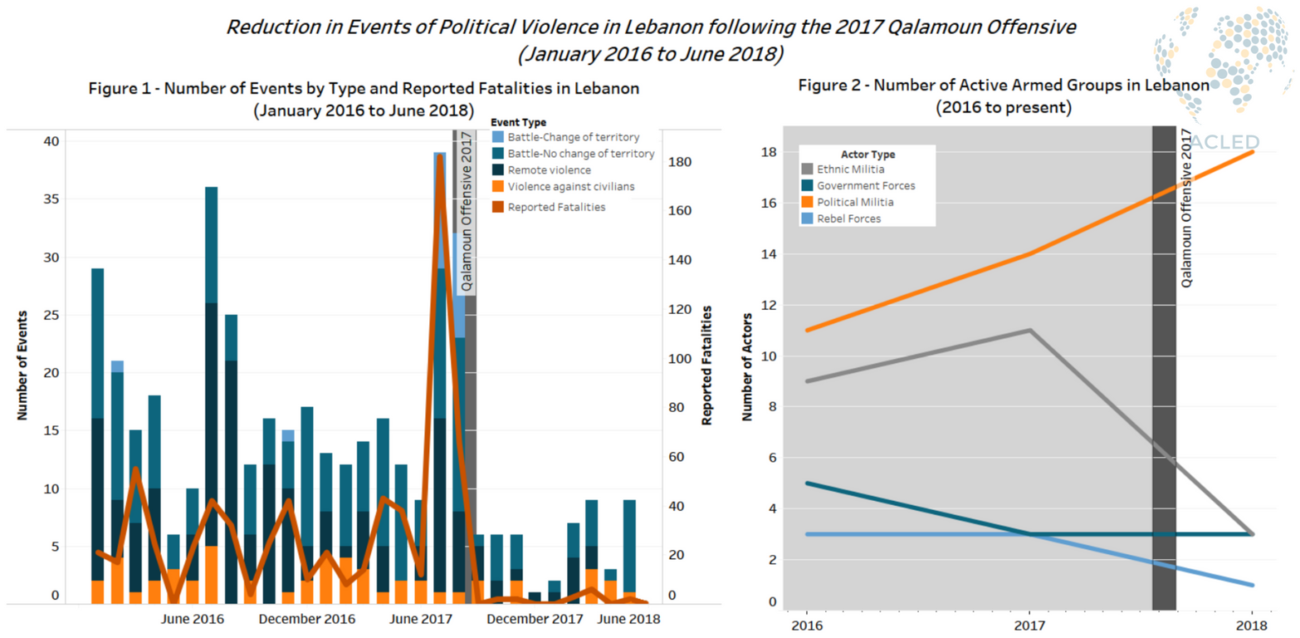

The 2017 Qalamoun offensive (see here for more on this topic) disengaged Lebanese territory from the Syrian Civil War resulting in greater stability in Lebanon. This can be seen in the overall reduction in the number of political violence events and reported fatalities in the country following the end of the offensive. The increased stability appears durable, particularly in light of the lack of reported political violence between armed groups before and after the Lebanese elections in May 2018.

Since the conflict began, Lebanon has been profoundly impacted by the Syrian Civil War. Between 2014 and 2016, the Lebanese parliament was unable to elect a president due to disagreements and an inability to reach a consensus over the country’s policy regarding Syria, including how to deal with Hezbollah’s intervention in the Syrian Civil War (Al Jazeera, 24 April 2014). Additionally, Lebanon has been host to over one million Syrian refugees since the beginning of the conflict (UNHCR, May 31, 2018), which has increased the population in Lebanon by as much as 25% and has caused further strain on already strained public services and infrastructure (URDA, 1 Jan 2017). Despite the political vacuum created by the lack of a president and increased pressure on public services across the early years of the Syrian Civil War, the Lebanese government maintained tenuous stability throughout much of the country while dealing with almost daily fighting along the Lebanese-Syrian border. It was this border instability which the Qalamoun offensive was designed to end.

Since the outbreak of the Syrian Civil War there have been four major battles in the Lebanese areas of the Qalamoun mountain range. The Qalamoun Mountains lay along the Lebanese-Syrian border and their ruggedness has provided a stronghold for rebel groups, particularly the Islamic State (IS), the Al Nusra Front, and groups affiliated with the Free Syrian Army (FSA). The final Qalamoun offensive lasted from 21 July 2017 to 28 August 2017 and included the participation of the Lebanese armed forces, Hezbollah, and Syrian government forces. This resulted in the Lebanese armed forces regaining control over the mountain range and driving the Syrian rebel groups which had occupied them out of Lebanon.

Following the Qalamoun offensive there has been an overall drop in political violence in Lebanon, coupled with a significant drop in reported fatalities compared to 2016 and the period of 2017 before the offensive (see Figure 1). This can be explained by the parallel drop in the number of active rebel groups in the country to effectively zero (barring one IS attack in 2018; see Figure 2), which was the intent of the offensive. The primary rebel groups pushed out of Lebanon by the Qalamoun offensive — the Islamic State (IS) and Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) (formerly the Al Nusra Front) — were also the groups involved in the most battles in Lebanon before the offensive. The other major group pushed out by the offensive was Saraya Ahl al Salam, an alliance of opposition groups based in the Qalamoun Mountains and associated with the FSA. In total, these three rebel groups were active in nearly half of all reported political violence in Lebanon between 2016 and the end of the Qalamoun offensive in August 2017. Given the high rate of activity of these groups, their successful expulsion during the offensive contributed to Lebanon’s greater stability, represented by lower levels of political violence and reported fatalities, in the latter half of 2017 and continuing into 2018.

A surprising trend to note is the increase in the number of political militias active in the country (see Figure 2), and the fact that this has not led to an increase in reported violence. One reason for this is that the activity by these newly-active political militias is almost exclusively related to conflict within Palestinian refugee camps, which tends to be quickly suppressed. Periodic violence in these camps is monitored and responded to by Palestinian security forces, which will typically work to contain outbreaks of violence within the refugee camps in Lebanon, such as the Ain al-Hilweh camp, when it flares up (Naharnet, June 27, 2018). This means that despite the rise in activity by new political militias, this has not led to an increase in the number of events of political violence or reported fatalities in the country. That being said, if this trend continues, the security services and reconciliation mechanisms currently in place to deal with these conflicts may become overwhelmed.

The durability of the lower levels of political violence achieved in Lebanon since the 2017 Qalamoun offensive can be seen more clearly in the relative lack of violence surrounding Lebanon’s May 2018 general election. It would not have been surprising if this election, which had been postponed since 2013 and came after the passage of a new electoral law, had been accompanied by a rise in political violence due to its potential divisiveness. This was of particular concern due to the potential for renewed sectarian tensions following the end of Lebanon’s civil war in the 1990s, which involved considerable sectarian conflict (see here for more on this topic). In spite of these concerns, Lebanon’s election was held without reports of any major clashes, which was seen in and of itself as a triumph (Brookings, May 17, 2018).

With a new government in place and the exclusion of Syrian rebel groups from Lebanese territory having been maintained since the end of the Qalamoun offensive, the outlook in Lebanon appears positive. Barring the potential expansion of political militias in the country, it seems likely that the increased stability the country has experienced since the offensive, in terms of fewer events of political violence and reported fatalities, is likely to remain durable for the foreseeable future.