Disorder spread across ACLED’s areas of coverage last year, with political violence and protest surging in more countries than they declined. These trends show few signs of stopping in 2019, as conflict and unrest threaten to expand in scope and scale. In this special report on 10 conflicts to worry about in 2019, ACLED analyzes the top flashpoints in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, providing key overviews of 2018’s developments as well as a preview of what to watch for in the new year.

To access a full copy of the report, click here.To view analysis of specific conflict zones, in no particular order, please click on the links below.

10 Conflicts to Worry About in 2019

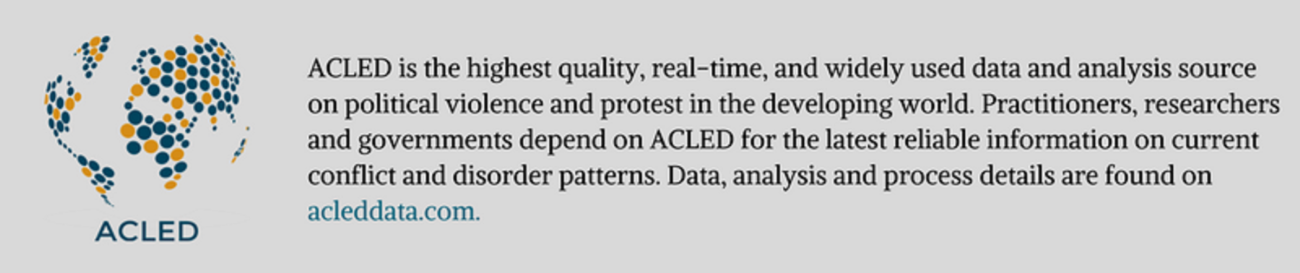

The Sahel: Most likely to be the geopolitical dilemma of 2019

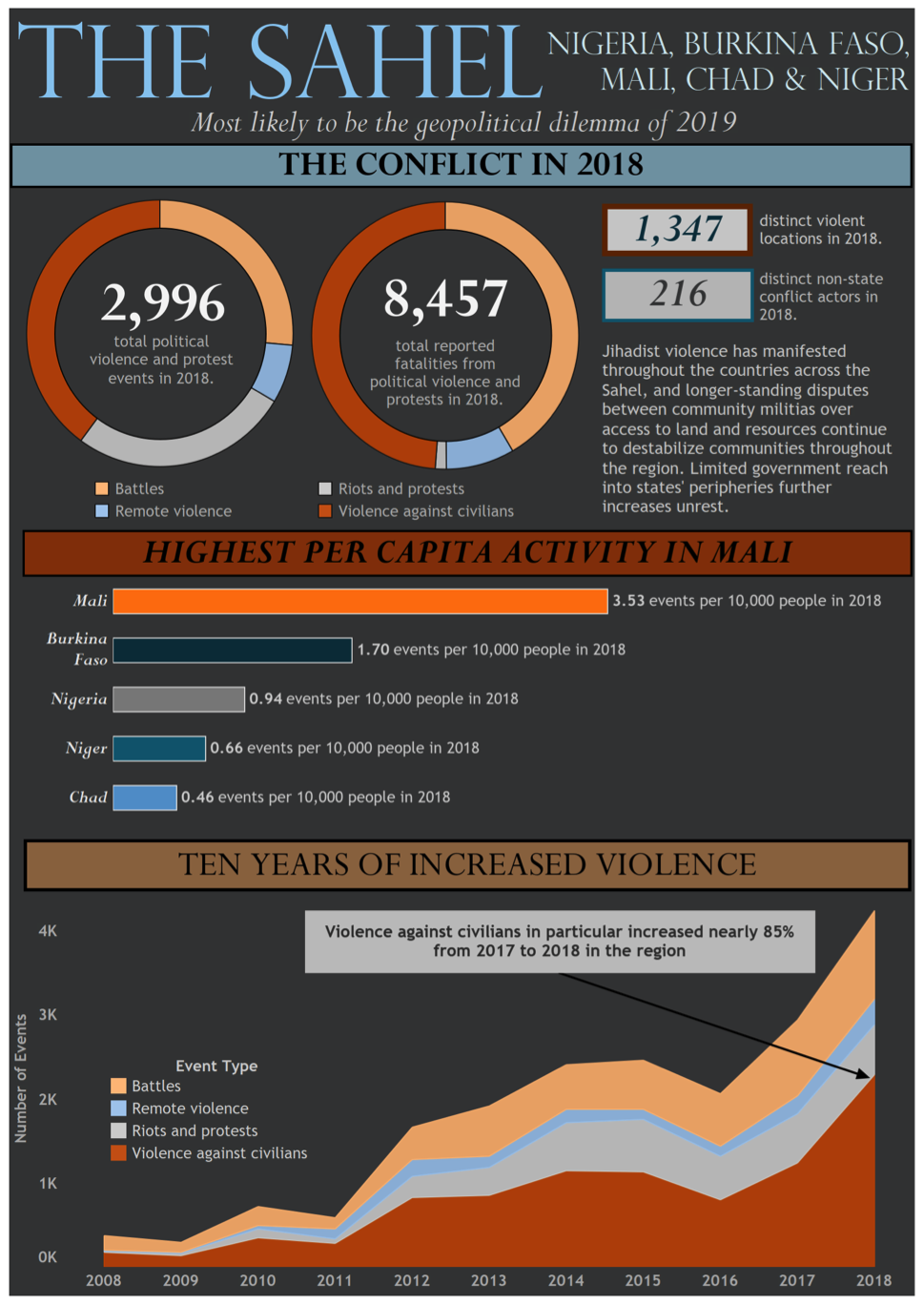

Yemen: Most likely to induce 2019’s worst humanitarian crisis

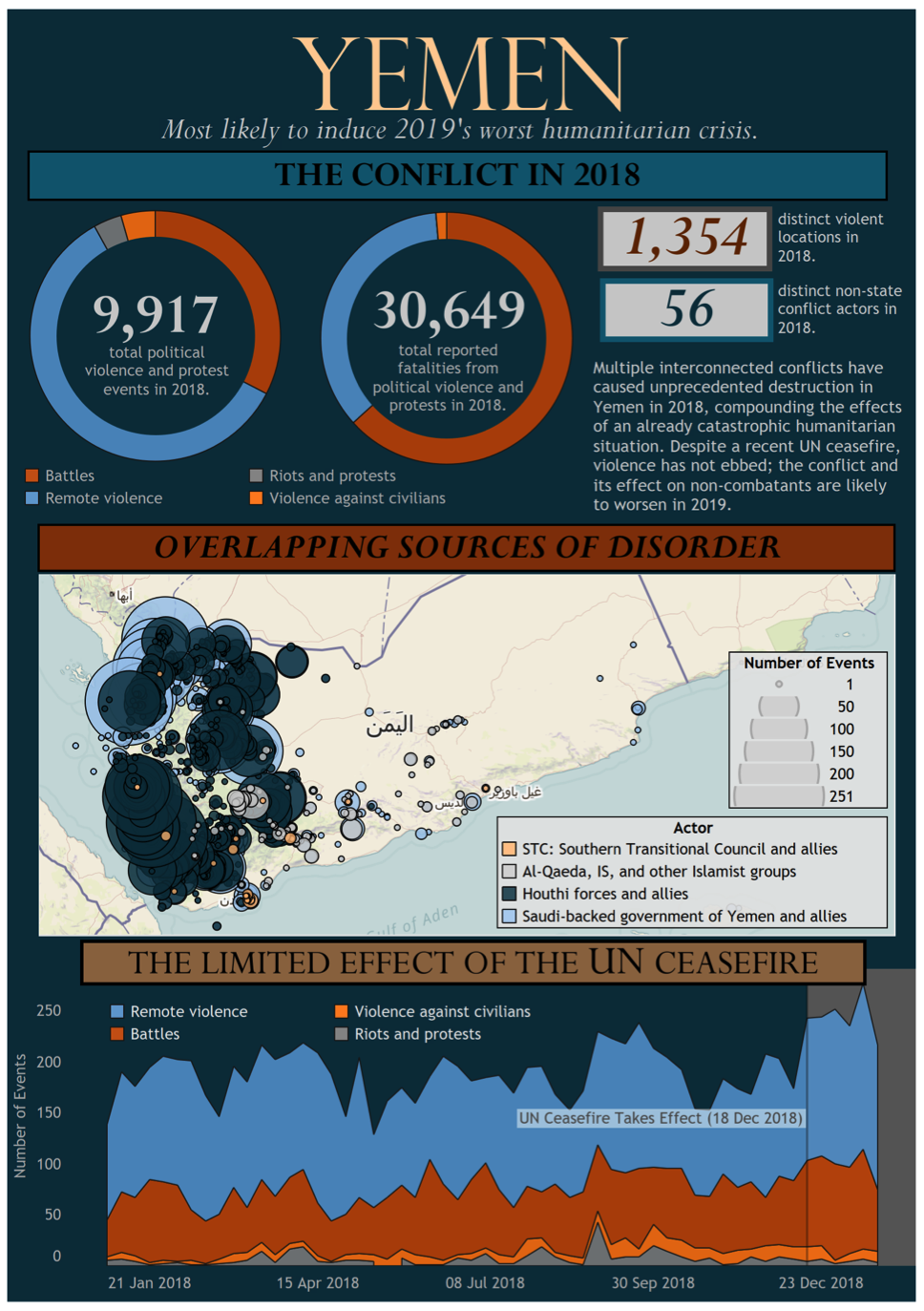

Afghanistan: Most likely to suffer from international geopolitics

Iraq: Most at risk of returning to civil war

Myanmar: Most likely to see expanding ethnic armed conflict

South Sudan: Most likely to see second-order conflict problems

Philippines: Most likely to see an increase in authoritarianism

Syria: Most likely to see a shift to mass repression

Libya: Most likely to see non-state armed group fragmentation and alliances

Sudan: Most at risk of government collapse

The Sahel: Most likely to be the geopolitical dilemma of 2019

Jihadist rebel groups and inter-communal fighting were potent sources of instability in the Sahel throughout 2018. The Boko Haram insurgency continued to destabilize communities across the Lake Chad Basin; in a particularly troubling show of force, the militants overran a number of locations between mid-November 2018 and mid-January 2019, including the town of Baga, in Nigeria, and the nearby military base. The 2019 election in Nigeria has featured extensive debate about incumbent President Muhammadu Buhari’s handling of the insurgency — and will also provide a tempting opportunity for the insurgents to debunk Buhari’s claim in December 2015 that they had been “technically defeated” (BBC, 24 December 2015). Concurrently, in Burkina Faso, jihadist violence continued in the country’s north and increasingly spread to the east. In both regions, jihadist groups have cultivated relationships between one another and with other criminal and armed groups in the area. These alliances make counter-insurgency operations particularly difficult — and suggest that 2019 will be a year in which the Burkinabe government struggles to loosen the jihadists’ hold in these territories. Likewise, in neighboring Mali, the center and north of the country remained sites of consistent jihadist rebel violence, while conflict trends at large continued to skyrocket, seeing one of the largest increases in the number of violent deaths in a country last year.

At the same time that countries across the Sahel have been grappling with shifts in the intensity and expansion of jihadist violence, inter-communal violence has also destabilized a number of communities in the region. Nigeria’s central ‘Middle Belt’ and central Mali, in particular, experienced significant violence involving communal militias. These conflicts commonly pit farming communities against herders — often a result of government policies that benefit one over the other. Conflicts between these actors, while typically described as ethnic or religious clashes, are in fact driven by fundamentally political issues like access to resources. In the absence of effective policy to mitigate resource conflict and clearly delineate fair usage patterns, this violence will continue. Community-based militias are increasingly targeting civilians as well: in 2018, nearly two-thirds of events involving these actors in this region were instances of violence against civilians; in 2017, violence against civilians accounted for approximately half of the events involving such groups.

What to watch for in 2019:

Moving forward, the lack of political solutions to both jihadist insurgencies and inter-communal violence across the Sahel will foster an environment that allows these conflicts to expand. Intercommunal violence will continue to follow seasonal patterns, even as it is additionally fueled by the intensity of competition over resources and cycles of retaliation. Given the extent to which jihadist groups across the region have been able to permeate communities historically marginalized by or disconnected from the central government, rebel activity will likely increase in both frequency and geographic spread in 2019.

Further reading:

Concurrent Crises in Nigeria

Fulani Militias in Nigeria: Declining Violence not a Sign of Lasting Peace

Burkina Faso – Something is Stirring in the East

Insecurity in Southwestern Burkina Faso in the Context of an Expanding Insurgency

From the Mali-Niger Borderlands to Rural Gao: Tactical and Geographical Shifts in Violence

Yemen: Most likely to induce 2019’s worst humanitarian crisis

Four years into the conflict, the scale of destruction in Yemen has reached unprecedented levels: estimates of 80,000 people having died as a direct result of the violence,[1] millions displaced, and an estimated 85,000 children killed by malnutrition and preventable diseases, while many communities across the country continue to live in famine conditions (Save the Children, 21 November 2018). ACLED recorded over 30,000 deaths in Yemen last year stemming directly from the conflict — a more than 82% increase in total reported fatalities from 2017.

The War in Yemen currently comprises a variety of interconnected local conflicts involving regional powers competing for influence. The first of these conflicts pits the Houthis, a Zaydi revivalist movement hailing from Yemen’s northern highlands that seized the capital Sana’a in 2014, against the internationally-recognised government of Yemen, led by President Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi. Hadi enjoys the support of Saudi Arabia and its allies, who launched a military intervention in support of the internationally-recognized government in March 2015 to prevent the Houthis from overtaking the southern port city of Aden.

The second conflict is linked to a secessionist bid by the Southern Transitional Council (STC): a political organisation established in May 2017 by former Aden governor Aidarus Al-Zubaidi and Salafist leader Hani bin Braik that advocates for the creation of an independent state in southern Yemen. The STC has extended its influence across Yemen’s southern governorate through a vast network of Emirati-backed militias, some of which are fighting against the Houthis in Hodeidah and, occasionally, against Hadi loyalists in several southern and central governorates.

The third main conflict is an Islamist insurgency launched by Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and the Yemeni branch of the Islamic State (IS). While both groups currently possess limited operational capacities in the country, AQAP controlled large swathes of territory in several provinces — including Mukalla, Yemen’s fifth-largest city — between 2015 and 2016. Often in competition with one another, AQAP and IS have also been reported to fight against the Houthis, alongside pro-government militias, in Al Bayda, Shabwah, and Ta’izz.

The collapse of the coalition between the Houthis and Yemen’s former president Ali Abdullah Saleh in December 2017 – just before Saleh was killed – broke the stalemate that had characterised the war in previous years. Although the Houthis have retained strong military capabilities despite the split, in 2018 they lost control of several key sites in Shabwah, Ta’izz, Ad Dali, Hajjah, Sadah, and, most importantly, in Hodeidah – the key port city contested by Emirati-backed troops in June. A UN-brokered deal in December spared Hodeidah from an all-out offensive, yet repeated violations of the ceasefire and occasional outbursts of fighting constitute a serious danger to the fragile agreement.

At the same time, cracks within the Saudi-led coalition emerged vigorously in 2018, revealing the weakness of its foundations: tensions between the STC and the central government resurfaced in southern Yemen, leading to violent clashes in Aden and to several assassination attempts targeting Islah-linked clerics; frequent episodes of infighting within the Emirati-backed coalition in Hodeidah, raising questions over the ultimate goals of the forces fighting on the western front; and the Saudi-Emirati row over the island of Socotra, which reflects the often diverging interests of the two regional powers in Yemen.

What to watch for in 2019:

2019 is already being met with a mixture of hope and scepticism over the prospects for peace in Yemen. The UN agreement — which stipulates a ceasefire and a redeployment of forces in Hodeidah, a statement of understanding on Ta’izz, and a prisoners’ exchange — was a first attempt to bring the parties to a negotiating table and break the cycle of violence. Accused of excessive vagueness, the agreement requires that all parties engage in a joint, serious effort, backed by constant international pressure, to implement the verification mechanisms and the redeployment of forces in Hodeidah, although repeated violations of the ceasefire and contrasting interpretations over its provisions already reveal the limitations. Its ultimate success or failure will be critical for the future of the War in Yemen in 2019.

Further reading:

Yemen’s Urban Battlegrounds: Violence and Politics in Sana’a, Aden, Ta’izz and Hodeidah

Special Focus on Coalition Forces in the Middle East: The Saudi-led Coalition in Yemen

Who are the UAE-Backed Forces Fighting on the Western Front in Yemen?

Targeting Islamists: Assassinations in South Yemen

Exporting (In)Stability: The UAE’s Role in Yemen and The Horn Of Africa

ACLED Methodology and Coding Decisions around the Yemen Civil War

Afghanistan: Most likely to suffer from international geopolitics

2018 has reportedly been one of the deadliest years in Afghanistan — ACLED reports over 43,000 fatalities in 2018 alone, making Afghanistan the deadliest country in the ACLED dataset, by far — although both the Taliban and Afghan regime have reason to keep these numbers low for recruiting and propaganda purposes (NY Times, 21 September 2018). The Taliban insurgency continues at full pace into 2019, despite offers to talk peace by President Ashraf Ghani, and an unprecedented ceasefire over Eid al Fitr (Nikkei Asian Review, 19 August 2018). Last year, the Taliban made some territorial gains during their annual spring offensive – codenamed Al Khandaq – particularly in the provinces of Faryab, Urozgan, and Ghazni. This offensive arguably remains ongoing in several provinces, although it peaked in July 2018, and was still very evident in August 2018 when the group launched a multi-pronged assault on the provincial capital of Ghazni province and multiple surrounding districts – several of which it reportedly captured. Despite only holding onto Ghazni city for a day, the Taliban nonetheless demonstrated their continued strength over a decade into the conflict. This show of force may gain them a stronger position during any future peace talks.

The emergence of the local Islamic State (IS) affiliate (Islamic State – Khorasan Province [ISK]) in 2015 added a new element of violence to the situation and created a common enemy for both the Taliban and the joint Afghan/NATO forces. It also added a serious threat for Afghan civilians.[2] Taliban offensives into Jowzjan province – in addition to Afghan and NATO operations – also seriously wounded the IS affiliate, as evidenced by at least one mass surrender on 31 July 2018 (RFERL, 2 August 2018). Later in August, the Afghan emir of IS, Abu Saad Erhabi, was killed by a US airstrike in Nangarhar – a further blow to the group. These attacks likely contributed to the significant drop in IS activity from September 2018 onwards. As of January 2019, it appears that joint efforts to eliminate ISK from the country by both Taliban as well as Afghan forces (alongside their NATO allies) have essentially limited the group’s presence to their stronghold in Nangarhar province.

Afghanistan’s ruling regime enjoyed a significant swell of support in 2018 as well, despite Taliban gains. This was most strikingly evidenced by the October 2018 parliamentary election, during which almost half of all registered voters ventured to the polls in the face of significant threats from both the Taliban and IS. The success of the long-delayed election demonstrates the Afghan people’s desire for peace and stability after years of constant warfare.

2018 ended with further peace talks – this time between a US envoy, the Taliban, and representatives from other countries. These talks purposely excluded Afghan officials from the debate, with the Taliban declaring that the US is their main adversary and that the Afghan regime is merely a “puppet” (Al Jazeera, 20 December 2018). Further talks took place recently, in January 2019, in Qatar, though once again without Afghan government officials — despite the fact that President Ghani remains open to talks. While the Taliban wants a full US withdrawal from Afghanistan, the US wants, amongst other things, assurances that groups like Al Qaeda and IS will not be allowed to use the country as a base of operations (Washington Post, 28 January 2019).

What to watch for in 2019:

At the end of 2018, unconfirmed reports were received from “unnamed” American officials claiming that a partial withdrawal of around 7,000 US troops would occur over the following months, surprising a number of parties, including some of America’s NATO allies (Telegraph, 21 December 2018). With the US and the Taliban now openly negotiating a deal around the American withdrawal (The New York Times, 24 January 2019), it remains to be seen how a US exit from the conflict will affect the Afghan government’s ability to maintain control over the majority of the country in 2019.

Further reading:

Violence against Civilians in Afghanistan: The Taliban and the Islamic State

Fighting Bullets with Ballots: Afghanistan’s Chaotic Election

Special Focus on Coalition Forces in the Middle East: The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) Forces in Afghanistan

ACLED Methodology and Coding Decisions around the Conflict in Afghanistan

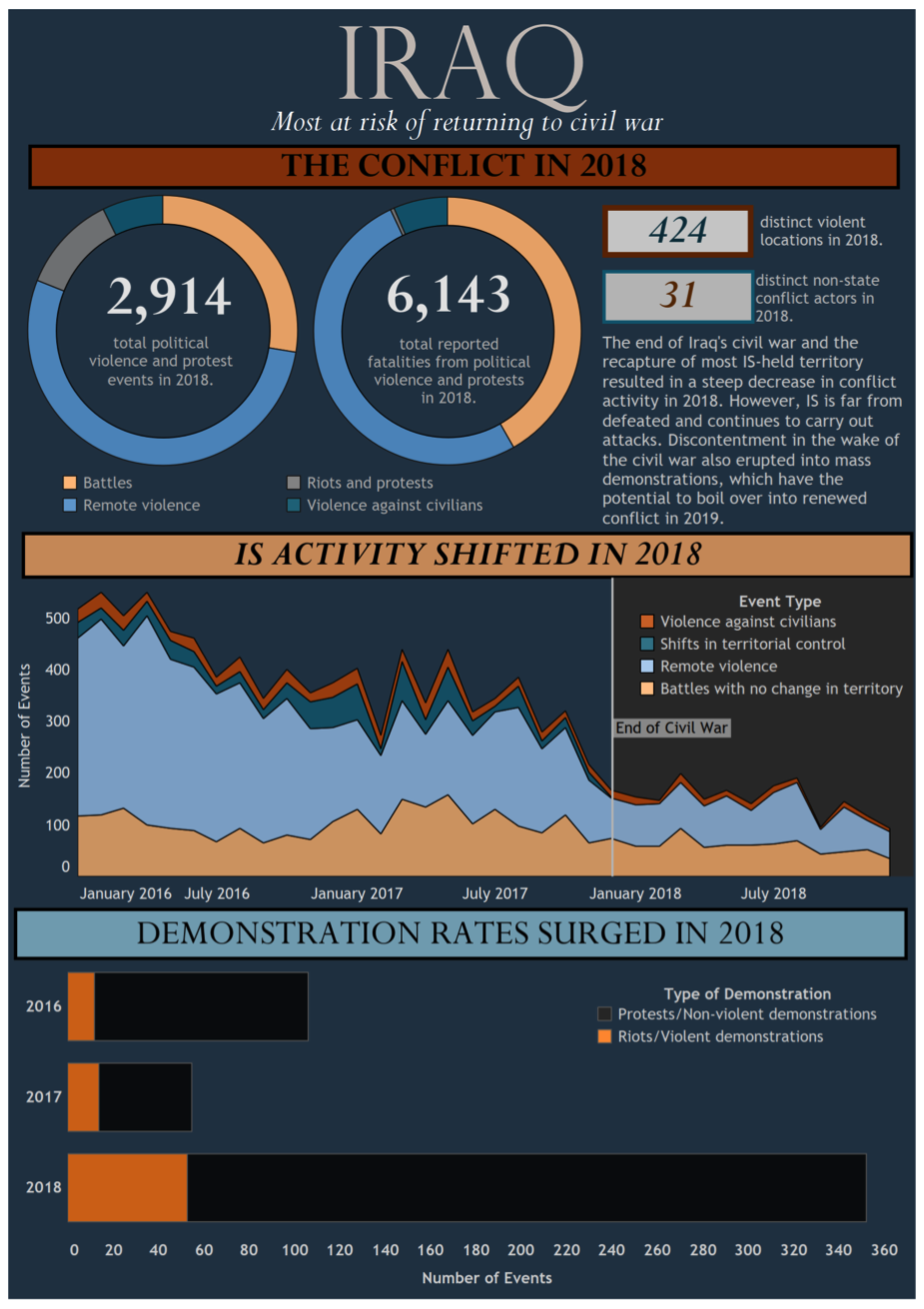

Iraq: Most at risk of returning to civil war

The first anniversary of Iraq’s ‘victory’ over the Islamic State (IS) was celebrated on 10 December 2018, as the nation begins to rebuild after four years of civil war. Violent conflict has been consistently decreasing throughout the country. While IS still maintains a relatively strong presence across the ‘colonization zone’ in Kirkuk, Sala al Din, Diyala, and Ninewa governorates, the group no longer holds territory and has shifted to a strategy of using primarily IEDs and other ambush tactics. This type of violence remains a significant threat to civilians, who are often the victims of such attacks.

Tensions are now rising between the different armed groups that were allied with the federal government in the fight against IS as they attempt to maintain power and relevancy in peacetime. The recapturing of Kirkuk — which contains oil fields and is a hub of oil transport in the region — on 16 October 2017 by Iraqi military forces and members of the Iran-backed Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) strained relations between the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and Baghdad, as well as between opposing parties within Iraqi Kurdistan that sought to blame others for the loss (VOA News, 19 October, 2017). The loss of resources and ongoing tensions, aggravated by the Kurdish referendum in September 2017, led to austerity measures and subsequent unrest throughout the region. In several cities, the political offices of the two major Kurdish parties – the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) and the Kurdish Democratic Party of Iraq (KDP) — were set alight, with demonstrators demanding unpaid salaries amongst other securities and services (CNN, 19 December, 2017).

Riots and protests erupted not only in Iraqi Kurdistan but also elsewhere throughout the country over the following months – notably in the southern governorates, centered on oil-rich Basrah. There is a clear correlation between the decrease in armed conflict between IS and government/allied forces and a subsequent increase in popular unrest in 2018. This shift is indicative of simmering tensions within Iraq, which the war with IS had thus far kept from surfacing. As the central government attempts to re-establish its legitimacy and authority, political groups and disenfranchised populations have taken to the streets to voice their dissatisfaction.

The vast majority of the demonstrations are calling for improved services and securities, as well as accusing the government of corruption and alleging Iranian interference (Al Jazeera, 22 July, 2018). The July 2018 Basrah demonstrations occurred just months after the May parliamentary elections, which many thought would lead to improvements in governance and quality of life. However, the recent resurgence of demonstrations in Basrah emphasizes that many of the same issues still exist and it is unlikely that a quick solution will emerge any time soon.

What to watch for in 2019:

At the beginning of 2019, the Iraqi people find themselves in a country still healing from a war that has been officially over for a year. Ongoing efforts by both state and Global Coalition forces have pushed IS further underground, sometimes literally — in recent weeks, there has been an increase in the destruction of IS tunnels and hideouts across multiple governorates. At the same time, US forces have reportedly established two new military bases in Anbar province in an attempt to thwart IS infiltrations from across the Syrian border (Press TV, 25 December 2018). On the other hand, the American withdrawal from Syria may lead to a resurgence of IS in that country, which could in turn affect Iraq. Should the threat from IS be dealt with effectively in 2019, the Iraqi government will need to simultaneously address competing interests — both internal and external — as well as a general population angry with its lack of focus on post-war development and jobs.

Further reading:

Special Focus on Coalition Forces in the Middle East: The Global Coalition Against Daesh in Iraq and Syria

The Reconstitution of the Islamic State’s Insurgency in Central Iraq

IS Underground: The Post-War Threat to Iraqi Civilians

Unrest in Basra Signals Growing Crisis

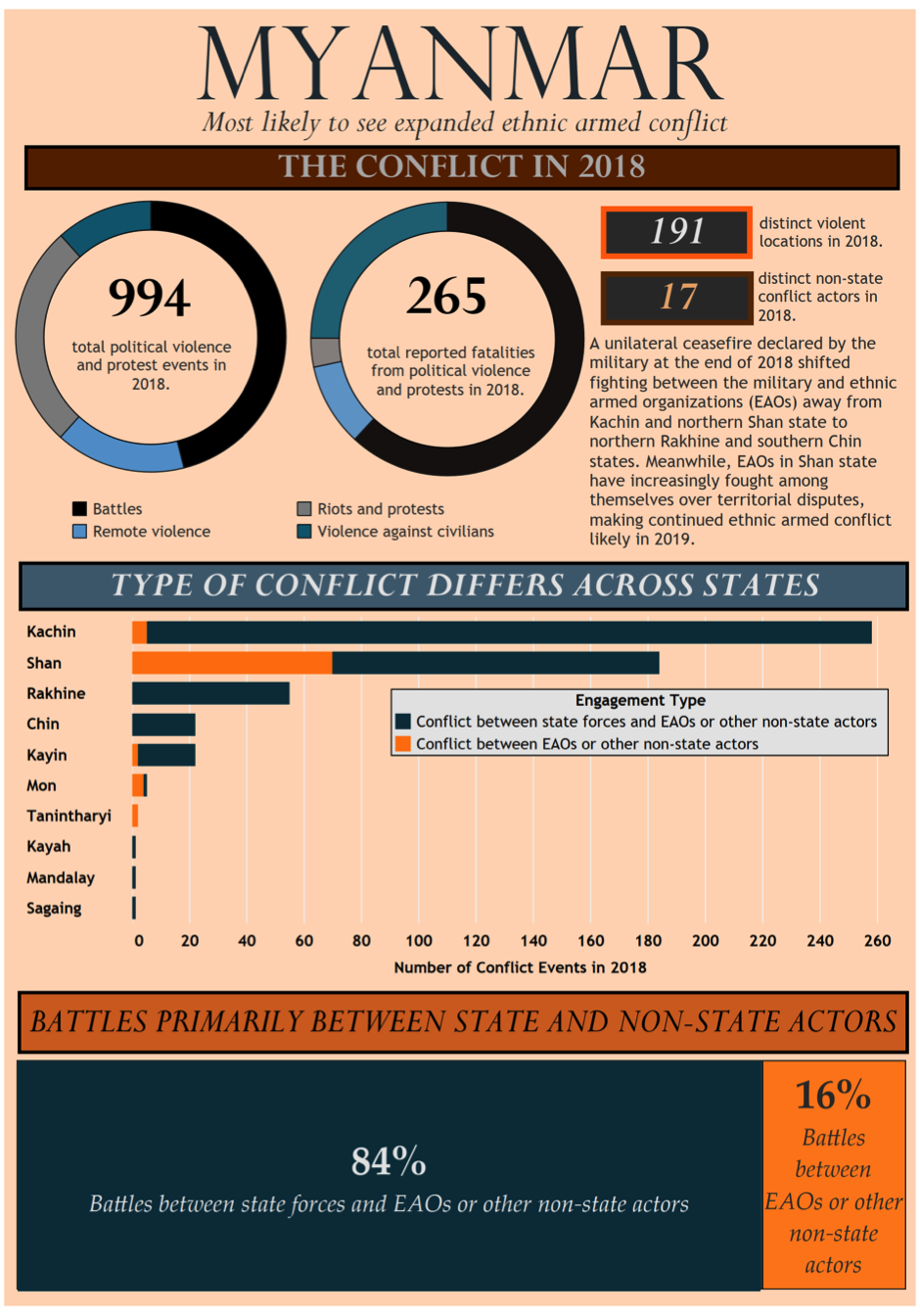

Myanmar: Most likely to see expanded ethnic armed conflict

Myanmar continued to experience significant ethnic armed conflict across the country in 2018. At the end of the year, Myanmar’s military announced a unilateral four-month ceasefire covering Kachin and northern Shan state — the site of continuous fighting between the military and ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) that have yet to sign the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA). While the ceasefire was met with cautious optimism, it has quickly become apparent that the military has directed its focus to Rakhine state, a region not covered by the ceasefire. Though fighting between the military and the Arakan Army (AA), an armed group comprised of ethnic Rakhine, had been on the rise prior to the ceasefire announcement, it has subsequently increased sharply and looks likely to continue well into the new year.

While the government and military have labeled the AA “terrorists” after they carried out an attack on four police stations in northern Rakhine state at the start of the year (Radio Free Asia, 7 January 2019), the AA has gained significant popular support among the Rakhine population (The Irrawaddy, 8 January 2019). The conflict between the AA and the Myanmar military is perceived by much of the Rakhine public to be a battle for ethnic equality and self-determination.

The AA is part of the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee (FPNCC), an alliance of seven EAOs that have not signed the NCA. By allying with more powerful EAOs — particularly the United Wa State Army (UWSA) and the Kachin Independence Organization/Kachin Independence Army (KIO/KIA) — the AA and other smaller groups have gained in numbers and military capabilities over the past few years. The formation of the FPNCC, which has strong ties to China, has also given its member groups greater leverage in negotiations with the military (Asia Times, 26 May 2018). While all FPNCC member groups operate in either Kachin or northern Shan state, the AA aims to establish a base in Rakhine state. Thus, the ceasefire announcement poses a challenge to both the military and the EAOs, as the continuation of fighting in Rakhine state threatens any peace talks with the FPNCC.

Notably, near the end of 2018, even before the ceasefire went into effect, fighting between the Myanmar military and the KIO/KIA was already waning following a significant spike in May. As alliances between armed groups in Myanmar are often fragile, it is unclear whether the FPNCC will remain intact given the military’s “divide and rule” strategy in negotiations with EAOs. For now, many EAOs, including those outside the FPNCC, have called for the ceasefire to cover all regions, including Rakhine state (The Irrawaddy, 28 December 2018). The FPNCC has also indicated that negotiations with the military should be inclusive of all seven members.

In 2018, there were two significant developments among those EAOs that have signed the NCA. The Karen National Union/Karen National Liberation Army (KNU/KNLA) and Restoration Council of Shan State/Shan State Army-South (RCSS/SSA-S), two key signatories to the NCA, recently suspended their participation in formal peace talks with the government and military. Further, after the recent ceasefire was declared, the military announced that it had been attacked by the RCSS/SSA-S, a charge the group denied (Channel News Asia, 28 December 2018). While the military and RCSS/SSA-S have fought sporadically even after the signing of the NCA, and the KNU/KNLA and military have clashed in 2018 and at the start of this year, the current state of talks between the military and the two groups is cause for concern should additional clashes occur in 2019.

Aside from the ongoing conflict between the Myanmar military and various EAOs, conflict between EAOs is likely to continue in Shan state in 2019. In northern Shan state, the RCSS/SSA-S and a joint force comprised of the Palaung State Liberation Front/Ta’ang National Liberation Army (PSLF/TNLA) and Shan State Progress Party/Shan State Army-North (SSPP/SSA-N) have clashed frequently over the past year. The PSLF/TNLA charges that the RCSS/SSA-S is encroaching on their territory, while the RCSS/SSA-S maintains its right to operate across Shan state (Asia Times, 16 August 2018). The RCSS/SSA-S has also clashed with the Pa-Oh National Liberation Organization/Pa-Oh National Liberation Army (PNLO/PNLA) over territorial disputes. More recently, the reported deaths of several ethnic Pa-Oh after an altercation with the RCSS/SSA-S have led to increased tension between the two groups (The Irrawaddy, 12 December 2018).

The ongoing armed conflicts in Myanmar also generated protest activity throughout the country in 2018. In the first half of the year, intense fighting in Kachin state gave way to a youth-led anti-war protest movement calling for an end to the country’s many armed conflicts. In the latter half of the year, rallies supporting the military were organized by the armed forces, the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), and other nationalist elements in the country. These rallies are likely to continue in 2019 as the military attempts to gain public support for its actions.

What to watch for in 2019:

Myanmar’s ethnic armed conflicts show no sign of stopping in 2019. The temporary ceasefire called by Myanmar’s military covering Kachin and Shan states is undermined by the conflict in Rakhine and Chin states. The ongoing conflict complicates the possibility of formal peace talks with EAOs that have not signed the NCA, including the FPNCC. Meanwhile, formal talks with EAOs that have signed the NCA have been stalled. All this takes place against a backdrop of rising fighting between EAOs themselves. A resolution to these many conflicts is unlikely in the short-term, thus raising the possibility of intensified unrest throughout 2019.

Further Reading:

Myanmar’s Changing Conflict Landscape

Myanmar: Peace Talks Belied by Ongoing Conflict in Rakhine and Chin States

Demonstrations in Myanmar

Understanding Inter-Ethnic Conflict in Myanmar

Analysis of the FPNCC/Northern Alliance and Myanmar Conflict Dynamics

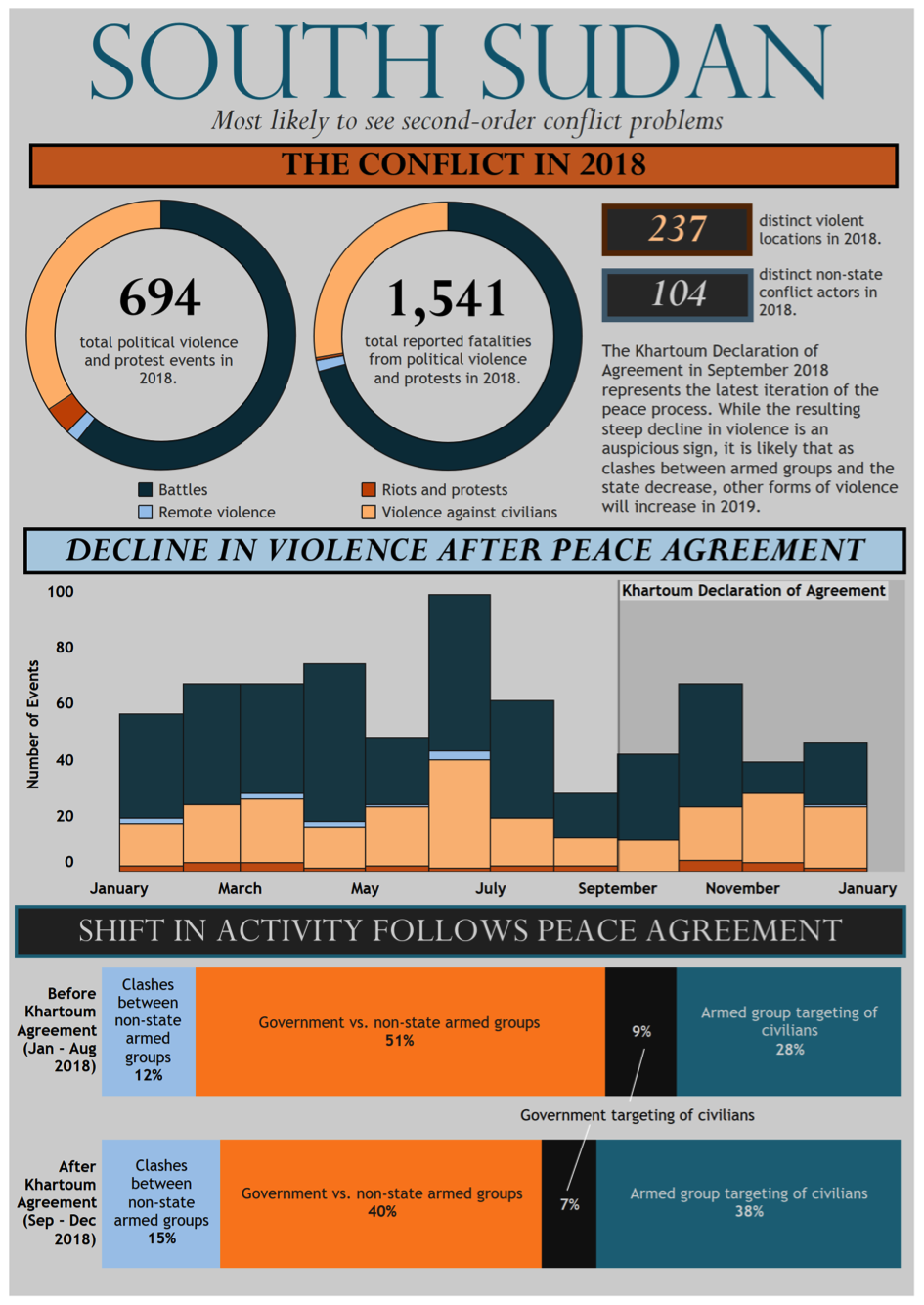

South Sudan: Most likely to see second-order conflict problems

South Sudan has been marred by conflict, both internal and external, since its founding in 2011. While inter-communal clashes and conflict with northern forces over resource rights were key causes of violence following independence, the lingering effects of South Sudan’s ongoing civil war have become leading drivers of insecurity in the country, even as events associated with the war declined throughout 2018. The current conflict — which began in 2013 as a result of a fracture within the country’s military, and has subsequently been marked by jockeying for political power among the country’s leadership — is dominated by violence against civilians along ethnic lines, as well as divisions and loyalties that trace back to the Sudanese civil war from 1983 to 2005. The two primary participants of the current conflict are the government of South Sudan and its armed forces (including the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, now rebranded as the South Sudan People’s Defence Forces, alongside special units outside of the army) headed by President Salva Kiir against the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-in-Opposition (SPLM-IO) headed by former Vice President Riek Machar. In addition to the government and the SPLM-IO, there are smaller rebel movements involved in the conflict as well as myriad militias of various affiliation throughout the country, which act both independently and in concert with the more dominant players. Over the course of 2018, total violence declined by nearly 50%, though general trends (the distribution of events by type, as well as the hotspots of violence) remained the same.

One of the most notable changes in 2018 — likely responsible for the sharp decline in violence overall — was the signing of the Khartoum Declaration of Agreement by both Riek Machar and Salva Kiir. Negotiations over the agreement, facilitated by political leadership from Khartoum and Kampala, began in June and an agreement was signed in September. The agreement incorporates not just the SPLM and the SPLM-IO, but also a number of the smaller rebel movements — although it was rejected by General Thomas Cirillo’s National Salvation Front (NAS), a significant rebel faction that has clashed with the military on many occasions after the signing of the agreement. Importantly, the agreement has enabled the resumption of production at certain oil facilities that have been offline since the early stages of the civil war — a fortuitous development for Sudan as well as South Sudan. As well as financing the newly enlarged Sudanese politico-military elite, the oil revenues will reassure Khartoum as it struggles with the current economic malaise in Sudan.

What to watch for in 2019:

As 2019 progresses, ‘second order’ conflict problems will likely continue — namely that inter-communal violence will likely rise, as it has done in the wake of previous peace agreements. Such a surge in inter-communal violence may be a function of the SPLM and SPLM-IO continuing to fight through proxy forces, a result of uncertainty over the distribution of political power among minor militias, or a mixture of both. The Khartoum Declaration of Agreement also contains a number of complex implementation provisions, providing ample opportunity for violence to spark in response to confusion or misperception. Despite these potential pitfalls, the ongoing violence between the SPLM and NAS forces may provide opportunities for cooperation between the SPLM and SPLM-IO in 2019, which will serve to improve relations and to demonstrate the capacity for cooperation between the primary conflict agents. So while this has the potential to improve the ‘first order’ conflict problems in South Sudan, it will be crucial to maintain a focus on the ‘second order’ conflicts as well.

Further Reading:

South Sudan: This War is Not Over

Conflict Activity in South Sudan

The Many Sides of International Peacekeeping in Africa

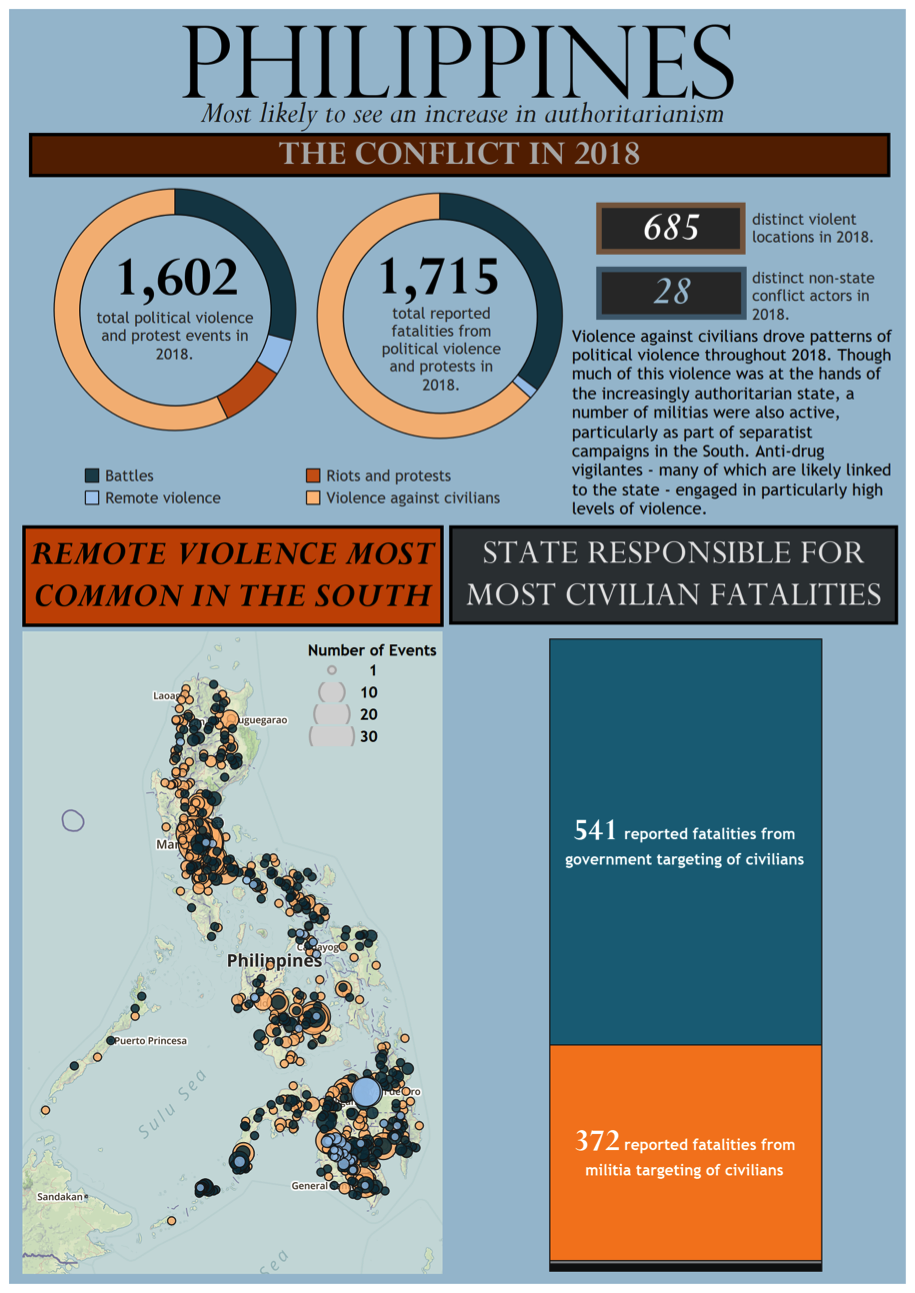

Philippines: Most likely to see an increase in authoritarianism

While the overall number of political violence events declined in the Philippines in 2018, high levels of state repression and the government’s lethal anti-drug campaign made it one of the deadliest countries for civilians in the world. Several contentious votes planned for 2019 threaten to enhance President Rodrigo Duterte’s authoritarian powers, to intensify ongoing violence, and to ignite simmering conflicts.

The country’s midterm elections, scheduled for May 2019, are already becoming a potential flashpoint, with violence against both opposition as well as supporters of the incumbent regime. In late December 2018, a Duterte-allied congressman running for mayor in Daraga in the upcoming elections was killed in an assassination allegedly orchestrated by the incumbent mayor (The New York Times, 3 January 2018). Multiple mayors and town councilors running for office were killed in pre-election violence across the country in 2018, and further increases in political violence in the run-up to vote are likely.

The elections will also impact President Duterte’s authority to wage his deadly ‘War on Drugs,’ which was responsible for the majority of attacks on civilians recorded by ACLED last year. At the beginning of 2018, the second phase of Oplan TokHang (part of the Philippine government’s ‘War on Drugs’) was declared, which saw an increase in the use of state forces to carry out violence against drug suspects. Now, at the start of 2019, a former mayor identified as a drug suspect by Duterte was killed in a police raid. The political weaponization of anti-drug frameworks to discredit and potentially mark rival candidates and officials for death is likely to continue — and intensify — as the vote draws near (The New York Times, 4 January 2019). While the elections are likely to return many pro-Duterte politicians, the potential for the opposition to make gains could have a moderating effect on the anti-drug campaign — a fact that may be fueling targeted attacks.

In addition to the drug war, Duterte has recently turned his attention to communist militants. Throughout 2018, the Philippine military and the New People’s Army (NPA) clashed repeatedly. These clashes have led Duterte to declare his intention to form a “death squad” to target the NPA. Further, the president has attempted to arrest the leaders of Bayan, an alliance of left-leaning groups, on what many see as politically motivated charges aimed at weakening left-leaning political opponents (Asia Times, 13 December 2018).

2019 will be a particularly important year for the Mindanao region of the Philippines. The first phase of the plebiscite for the Bangsamoro Organic Law (BOL) has passed and will lead to the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) becoming the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM). The second phase of the plebiscite, scheduled for early February, could lead to the incorporation in the BARMM of additional provinces not currently part of the ARMM. While the creation of the BARMM provides greater autonomy for the region (The Diplomat, 2 October 2018), there are concerns over how armed groups in Mindanao will respond to the plebiscite (Rappler, 8 January 2019).

Despite hopes for peace, on 27 January, a bomb exploded in front of a Catholic cathedral in Jolo in Sulu province, which voted against the BOL. The bomb was planted by a subgroup of Abu Sayyaf (ASG), which has declared allegiance to the Islamic State (Asia Times, 28 January 2019). While granting further autonomy to the Mindanao region has perhaps calmed the conflict with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), the threat of Islamic State-linked militants — including ASG, the Maute Group, and the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF) — in the southern Philippines remains (Asia Times, 1 November 2018). Martial law has been extended for another year in Mindanao (ABS CBN News, 29 January 2019) as the military continues to engage with all three groups — fighting that will likely continue into 2019.

What to watch for in 2019:

As Duterte looks to further consolidate power and shore up support for his ‘War on Drugs,’ the Philippines is at high risk of continued election violence in 2019. Simultaneously, anti-drug operations will remain a serious threat to civilians, with anyone alleged to be a drug user or dealer — in truth or for strategic gain — targeted as a matter of policy, including politicians. The threat to the country’s political opposition — as well as increased authoritarianism more largely — will only be amplified if the president follows through on his promise to target communist militant groups and leftist civil society organizations alike. In the south, ongoing conflict against Islamic State-backed militants could evolve into a renewed crisis as the Philippines’ volatile Mindanao region votes for greater autonomy from the central government.

Further Reading:

Duterte’s War: Drug-Related Violence in the Philippines

“Ninja” Cops: Duterte’s War on Police Linked to Illegal Drugs in the Philippines

ACLED Methodology and Coding Decisions around the Philippines Drug War

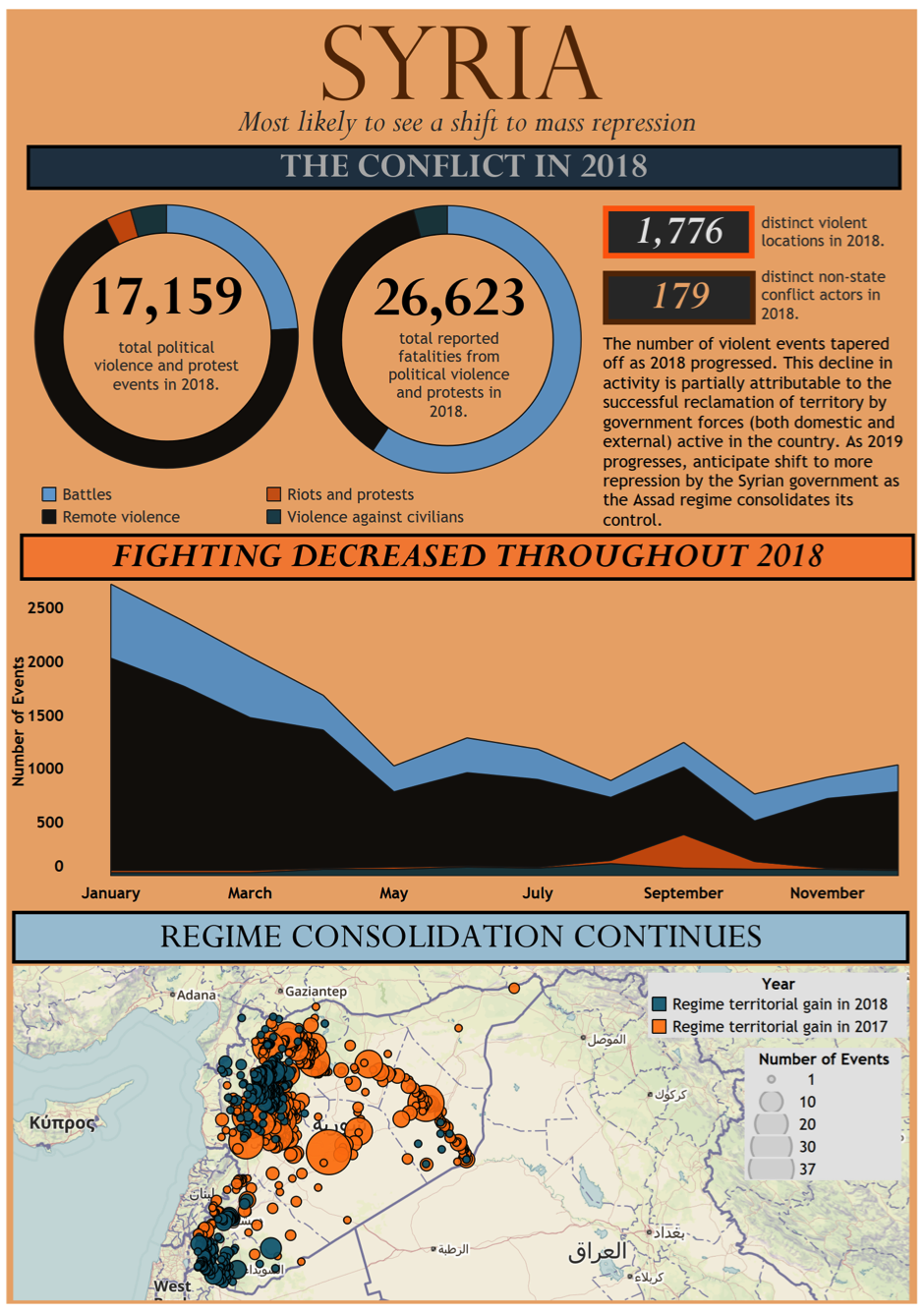

Syria: Most likely to see a shift to mass repression

Nearly eight years from the start of what began as a peaceful, popular uprising to demand increased freedom — though quickly transformed into a militarized, highly fragmented, and high-stakes conflict — the Syrian War today is marked by ever-expanding regime control and the complicating agendas of powerful regional and international actors.

Significant changes in territorial control occurred across 2018 as the regime regained its hold over southern and central Syria from opposition forces, including by retaking northern Homs, Eastern Ghouta, and areas of Hama, Aleppo, and Idleb. The regime additionally forced the surrender of opposition elements in Eastern Ghouta and the southern provinces.

The fight against the Islamic State (IS) in Syria also saw significant, if slow, progress as both the regime and its allies, as well as the Syrian Democratic Forces (QSD) and its Global Coalition partners, contributed to reducing IS territorial control. Regime forces, with Russian support, managed to retake all IS territory west of the Euphrates River and to push IS out of southern Syria, thereby limiting IS presence to a desert pocket south of the river. Concurrently, by the end of 2018, QSD and Global Coalition allies had reduced IS presence east of the Euphrates to a small stretch around Hajin.

Geo-political maneuvering also assumed an increasingly important role in the conflict in the latter half of 2018, as various regional and international actors leveraged the territorial control of their on-the-ground allies, during armed offensives as well as political negotiations. With the Assad regime capitalizing on the support of Russia and Iran, Turkey standing firmly behind rebel groups in the northwest, and the Global Coalition Against Daesh providing cover for the QSD in the northeast, a fragile status quo was maintained across spheres of control near the end of the year as efforts towards a political settlement were revived.

What to watch for in 2019:

2019 could see a major regime push to defeat the last rebel enclave in Idleb as Hayat Tahrir al Sham (HTS), the dominant Islamist militant group in the area, consolidates its position against rival opposition forces. A significant consideration regarding future control of Idleb will be attempts to open the trading roads (M4 and M5 highways) linking Turkey with Jordan through Syria now that the country’s southern border with Jordan has been reopened. With HTS controlling most of the enclave, and in light of recent HTS advances on rival rebel territory in the area, more of Idleb might fall to HTS in 2019. This will mean either accepting and negotiating with HTS as the actor who controls this trading route as it passes through Idleb, or it will mean a renewed and intensified regime and Russian offensive against the militant group.

Following the US decision to withdraw from Syria, it is highly likely that the QSD and the regime will come to an agreement that allows regime forces to deploy in QSD areas, uniting these Kurdish-held provinces in the northeast with the regime’s other territories. This would also likely result in Iran assuming an increased role in the area, which is a key piece of its “land bridge” to Hezbollah in Lebanon. However, with Turkish intentions to initiate an offensive against Syrian Kurdish groups along its southeastern border, negotiations between Turkey, Russia, and the US could result in shared control of QSD territories between Turkey and the regime. In the latter case, conflict may escalate as Turkey moves to eliminate any armed Kurdish presence from its border.

Finally, it is highly likely that IS sleeper cells across the country will continue — and perhaps increase — their operations against Kurds, rebels, and regime forces alike. As long as no joint effort is coordinated to eliminate IS remnants from the Syrian desert following the US withdrawal, IS fighters are likely to regroup and launch more organized attacks on key cities such as Al Bukamal, Sokhneh, or Tadmor.

Further reading:

Violence in the Eastern Ghouta, Syria

Reclaiming the South: The New Regime Offensive

Leading from Behind: Global Coalition Support Crucial against Islamic State in Syria

Divide and Conquer: Iran, Russia, and Loyalist Militias in Syria’s Deir-ez-Zor

Upping the Ante: Turkey Renews its Campaign against the YPG in Northern Syria

Operation Olive Branch: Patterns of Violence and Future Turkish Offensives

IS After ‘Defeat’: Guerilla Tactics in the Desert

Methodology: Mapping Territorial Control, Contestation, and Activity in Syria

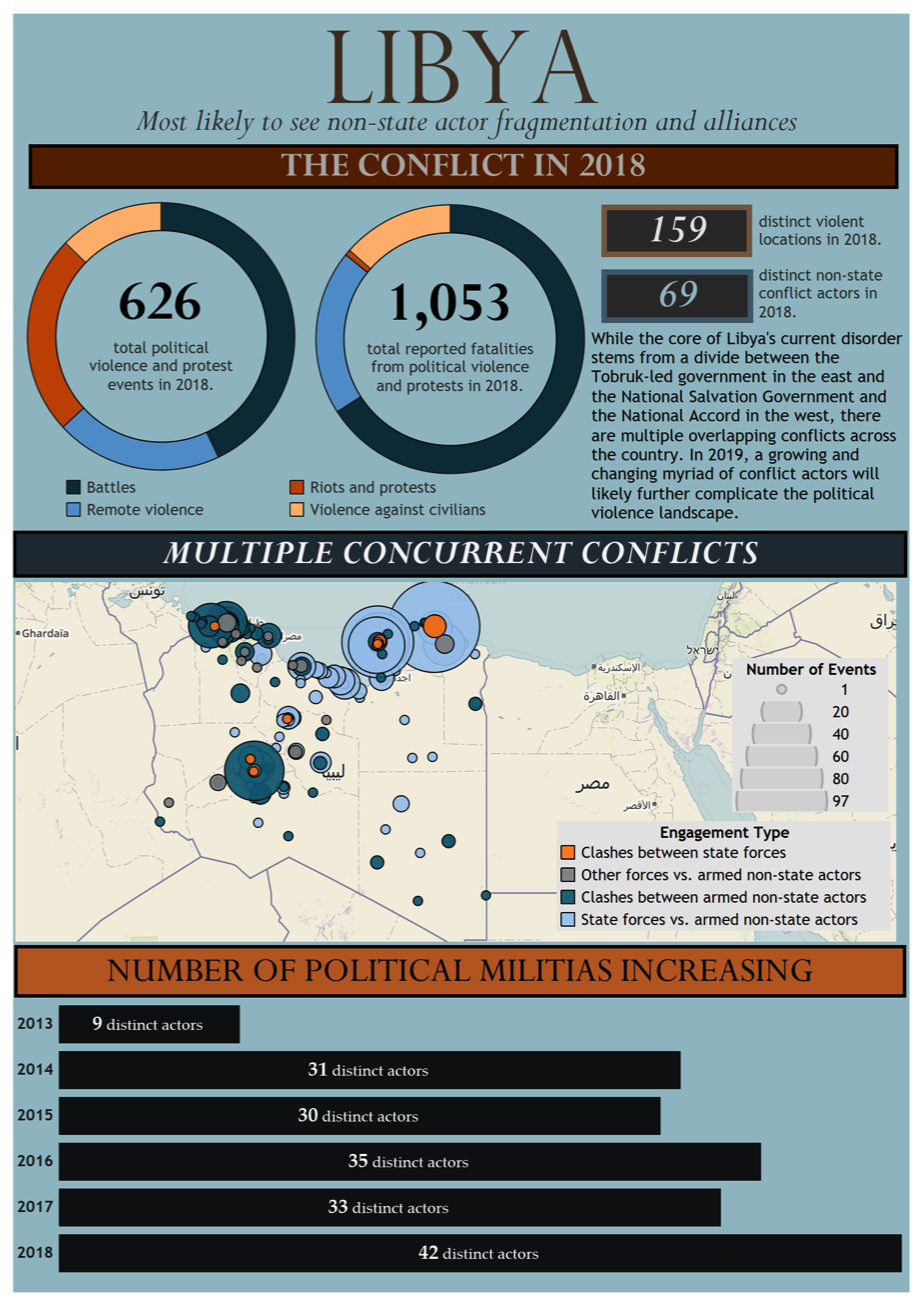

Libya: Most likely to see non-state armed group fragmentation and alliances

Effects of 2011’s ‘Arab Spring’ and subsequent civil wars continue to drive deep instability in Libya. In the immediate aftermath of the fall of former ruler Muammar Gaddafi, the country experienced a period of factional violence: a broad and multi-sided conflict when militias refused to disarm and assert their influence. Since 2014, a second, multi-sided civil war has seen a proliferation of disparate armed groups, including the Islamic State (IS), as well as a deepening of political divisions, an exodus of refugees, and mass casualties. The core of the current Libyan conflict is a political divide that roughly could be described as between the East (Cyrenaica) and the West (Tripolitania), and a neglected South (Fezzan). The divided Libyan security sector has been forced to contend not just with infighting and rebel groups, but also with Chadian and Sudanese armed groups, who seek to exploit the vacuum created by the lack of political consensus and security unity.

The self-styled Libyan National Army (LNA), led by Field Marshall Khalifa Haftar, saw relative success at the outset of 2018. In the previous summer, a coalition of Islamist militants were defeated by LNA forces in Benghazi following three years of fighting. After losing the city, the Islamist groups were largely relegated to small enclaves in already disputed territory, mainly southeast of Tripoli. While Benghazi has experienced a significant decrease in political violence, criminal violence is soaring. Despite IS’ movement south, the group continues to engage in small yet frequent attacks against a multitude of actors in the region, as well as a shift in activity towards increased engagement in battles and complex attacks targeting state institutions. There are concerns that 2019 may witness a continuation of the 2018 resurgence, despite the fact that the group’s capabilities have been degraded after suffering a number of tactical defeats amidst armed engagements with the LNA.

LNA secured additional gains throughout the year, namely with a large victory at the Battle of Derna, defeating an amalgamation of Islamist militias under the aegis of the Shura Council and later the Derna Protection Force. The victory in Derna was especially notable as the city was the last urban Islamist stronghold within the country. Despite the decisive victory of the LNA, and despite the fact that the city was declared liberated in late-June 2018, there still remain pockets of resistance in the Old City. Nevertheless, the Derna battle will inevitably come to an end, but there is a high risk that the ruined city will meet a similar fate as Benghazi, with criminal activity seeing a notable rise, replacing political violence as a destabilizing force.

Major battles also took place in Sebha and Tripoli, predominantly over territorial control: in Sebha, between Awlad Suleiman and Tebu; in Tripoli, between a large number of militias who each want their share of the security authorities as well as varied criminal activities. Recently, LNA units have made inroads in the area of Saddada and near Bani Walid — allegedly preemptive operations against Jathran and remnants of the Saraya Defend Benghazi (SDB), an Islamist militia opposing the Libyan National Army and Haftar forces in Benghazi — but could also be viewed as the LNA extending its influence into the western region. At present, the LNA is conducting a large-scale military operation in the south and has taken control of strategic locations in and outside Sebha through arrangements with the Tebu, possibly by payment and/or ceding territory further south. Highlighting this, the LNA utilizes a combined approach of direct military engagements and local arrangements to expand its influence; the question is if it will be able to effectively consolidate control of areas where it is expanding its military presence.

What to watch for in 2019:

Libya’s civil war remains ongoing in 2019, with entrenched divisions between the two rival governments fostering an unstable environment conducive to the resurgence of militant groups like IS. The myriad of militias, government forces, and rebel groups have created a situation in which alliances have been formed on temporary conveniences rather than long-term goals. It is likely that southern Libya will be a focal point of the conflict in 2019: the LNA is already expanding its presence in the south and has taken control of Sebha, while the presence of IS, in addition to Chadian and Sudanese armed groups, constitute a major source of insecurity in the region, as they will seek to maintain a solid base of operations. Yet, it is unclear how durable local arrangements will be — particularly if the LNA is unable to continue to make payments that may underlie some of these agreements. Furthermore, a security presence is not the same as governing — so the expansion of the LNA presence throughout the country does not necessarily portend political stability. Simultaneously, the country’s western region is also at risk of significant flare-ups against the backdrop of successive and fragile ceasefires.

Further reading:

Targeting Tripoli: Newly Active Militias Targeting Capital in 2018

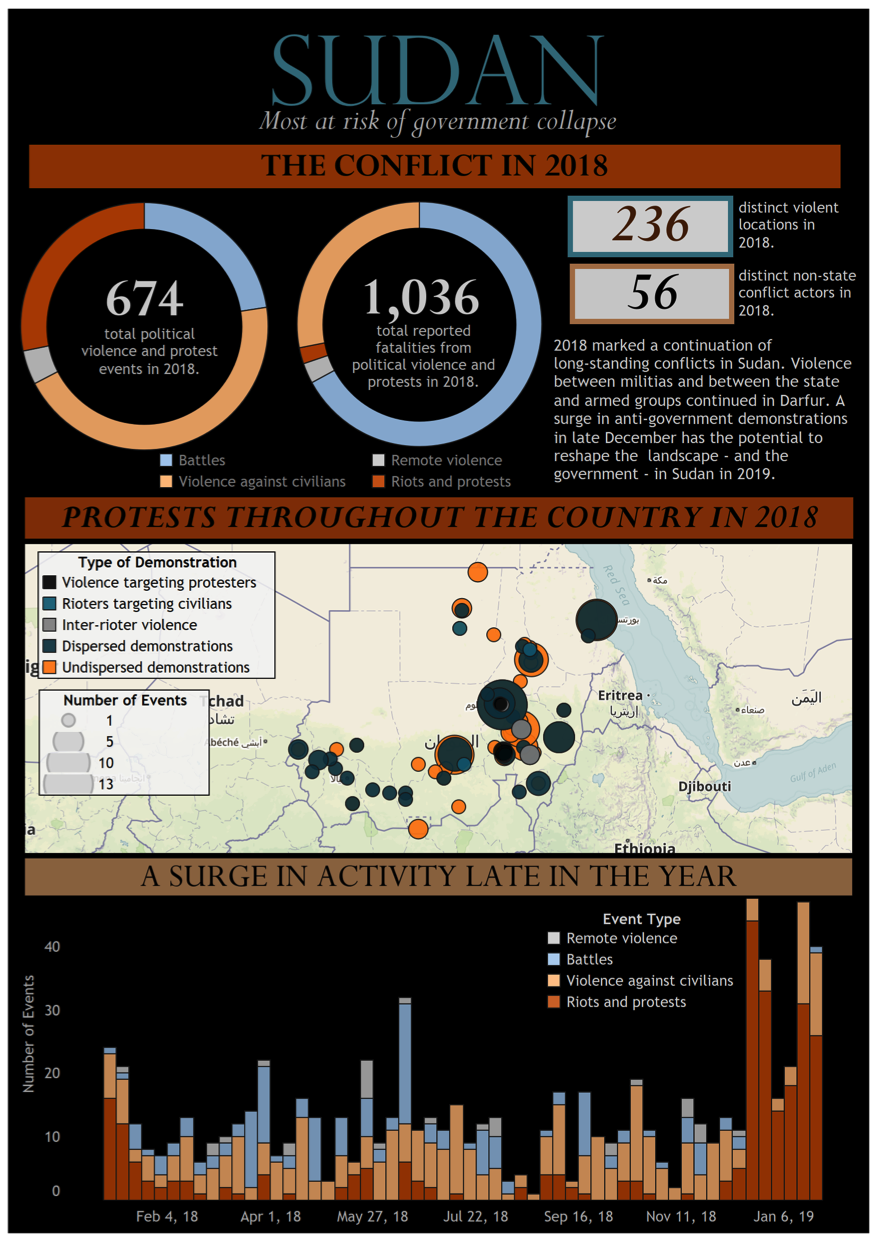

Sudan: Most at risk of government collapse

Events in Sudan throughout 2018 were largely variations on themes that have marked the country’s political landscape for more than a decade. Overall levels of conflict fell, though the core politics and grievances that have driven violence and protest in the country remain — with an eruption of mass demonstrations in late December, making 2019 a year fraught with uncertainty for the current regime of President Omar Bashir.

In the country’s west, violence in Darfur continued in 2018. This conflict was comprised not just of clashes between the Sudanese government and rebel groups, but also of fighting between various militias in the region. The targeting of civilians by a variety of armed groups also continued in 2018, and violence remained particularly concentrated around Jebel Marrah. With the drawdown of the AU-UN peacekeeping mission in the region, the violence may be driven by groups competing for dominance in the new environment. The targeting of civilians by the Sudanese government in Darfur rose in 2018, indicating that the regime could pursue a policy of collective punishment against the region’s citizens.

Toward the end of the year, the Sudanese government signed a pre-negotiation agreement with two of the armed groups active in Darfur with the intention of restarting talks in 2019 (Sudan Tribune, 2 December 2018). Previous peace agreements have been undermined by a failure to bring all groups to the table and an obscuring of the role of inter-militia violence as a driver of insecurity. Several rebel groups (including the Justice and Equality Movement [JEM] and the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army-Minni Minnawi [SLM-MM]) have continued to renew their unilateral ceasefire agreements with the government, which have been reciprocated by the Sudanese government (Dabanga, 7 December 2018).

The country’s east — particularly the capital, Khartoum — was marked by demonstrations in 2018, especially late in the year. Demonstrations over a fuel subsidy that began in early 2018 tapered off quickly; in January 2018, there were 39 demonstration events across the country, though February saw only seven. From then on, demonstration activity in the country remained fairly low — until December. The ongoing wave of demonstrations that began that month originally erupted over the removal of a subsidy on flour, undertaken as part of a neo-liberal economic recovery plan aimed at quelling IMF concerns about the country’s economic stability. The new policy led to soaring bread prices and a decline in availability. The demonstrations themselves have since expanded, however, to include a broader range of grievances and have taken on a distinctly anti-Bashir tone. There have been over 100 demonstration events throughout the country from December through the beginning of January 2019. As before, there were clashes between the security sector and the demonstrators, including instances in which the government used tear gas and live ammunition to disperse groups (Al Jazeera, 31 December 2018).

What to watch for in 2019:

The demonstrations in December quickly expanded from initial grievances about the economy to broader complaints about Bashir’s government, with some demonstrators demanding his resignation from office after nearly 30 years in power. The country is at an inflection point now, with much depending on whether Bashir calculates whether a crackdown or concessions to the demonstrators will best serve his long-term interests. If Bashir chooses the latter, it is not clear whether they will be honoured — and this uncertainty may allow the demonstrations to continue, even in the face of supposed commitments. Regardless of which tactic he chooses, the early months of 2019 will likely see an insecure Bashir attempt to coup-proof his regime. Moreover, Bashir’s indictment by the International Criminal Court (ICC) provides a serious disincentive for him to leave power. With limited financial backing by regional supporters — such as Qatar (Sudan Tribune, 23 January 2019) — Bashir’s regime could be facing collapse. This could result in a surge in violent activity associated with political militias and factions of the military throughout the country as unrest persists. The apparent failure to bring all rebel groups and armed militias to the table for the peace talks scheduled for 2019 suggests that the conflict in Darfur will likely drag on as well. Violence over access to resources, including civilian targeting in the course of inter-militia conflict, will continue until a workable political solution to the problem of resource sharing is developed. Instability in Sudan will have regional ramifications, as the country has played an active role in peacemaking efforts in the region, including in South Sudan and the Central African Republic.

Further reading:

Flour Power: Protests and Riots in Sudan in December 2018

Fuel Crisis Prompts Protests in Sudan

Inter-Communal Conflict in Sudan

10 Hidden Conflicts in Africa: #4 Darfur and its Armed Non-State Groups

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] ACLED reports that over 60,000 people have died thus far as a result of direct wartime violence since 2016 (ACLED, 11 December 2018), with estimates that the total spanning back to 2015 are closer to 80,000 (The Independent, 26 October 2018). ACLED plans to release Yemen data spanning back to 2015 later this year.

[2] IS tactics typically involve targeting civilian gatherings with high fatality suicide attacks, often in Shiite neighborhoods — such as the 22 April 2018 Kabul bombing that reportedlykilled 69 people and injured 120. The Taliban, on the other hand, is deeply rooted in Afghanistan at the local-level and requires the support of the people to further its goals.