In our special report on 10 conflicts to worry about in 2019, ACLED assessed the state of political violence and protest across critical flashpoints in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, providing both an overview of 2018’s developments and a preview of what to watch for in the new year. Our Mid-Year Update revisits these 10 conflicts more than six months on and tracks key disorder trends going into the second half of 2019.

Access the full update here, and access the original report here.

To view analysis of specific flashpoints, please click on the links below.

Mid-Year Update: 10 Conflicts to Worry About in 2019

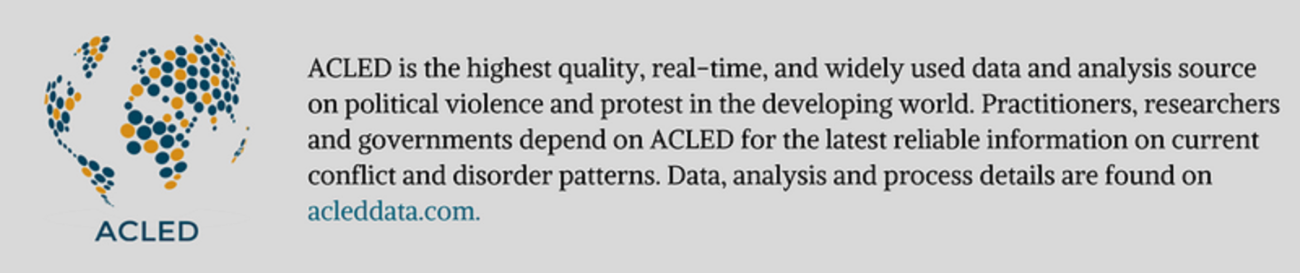

The Sahel: Most likely to be the geopolitical dilemma of 2019

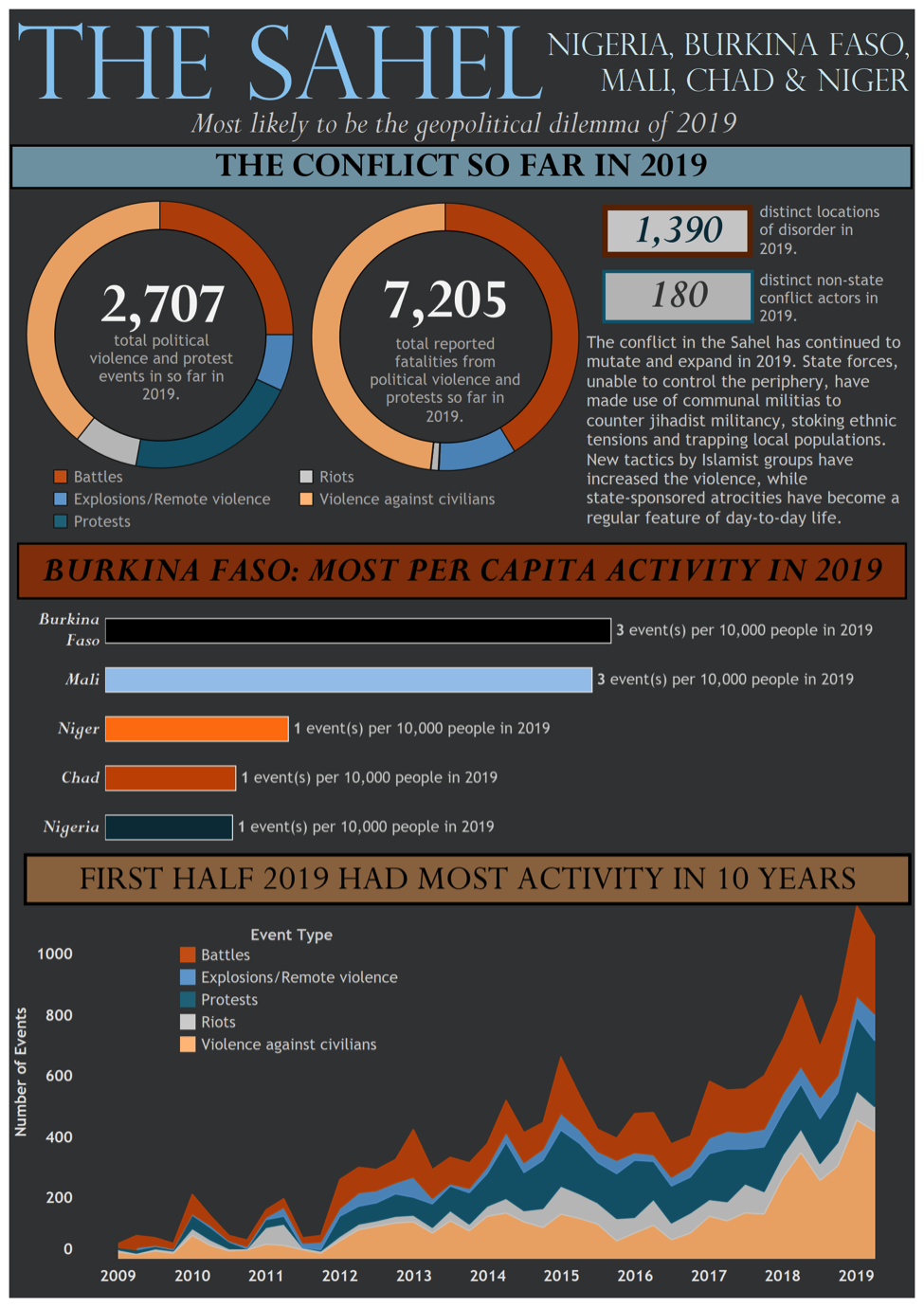

Yemen: Most likely to induce 2019’s worst humanitarian crisis

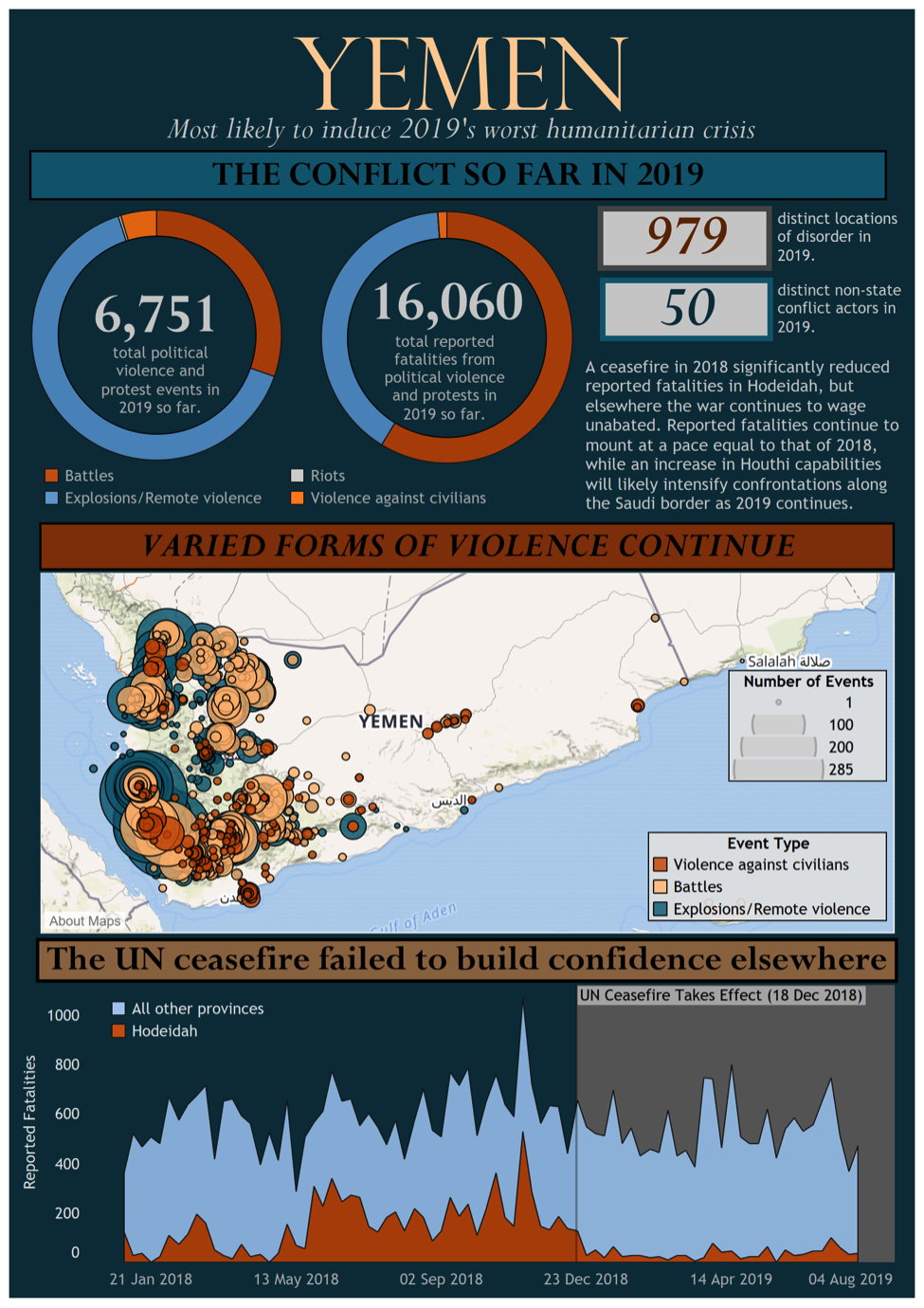

Afghanistan: Most likely to suffer from international geopolitics

Iraq: Most at risk of returning to civil war

Myanmar: Most likely to see expanding ethnic armed conflict

South Sudan: Most likely to see second-order conflict problems

Philippines: Most likely to see an increase in authoritarianism

Syria: Most likely to see a shift to mass repression

Libya: Most likely to see non-state armed group fragmentation and alliances

Sudan: Most at risk of government collapse

The Sahel: Most likely to be the geopolitical dilemma of 2019

The political violence landscape in the Sahel has expanded and shifted in 2019. Intercommunal conflict and Islamist violence continue to present obstacles to peace and security in the region, while demonstrations regarding government response to the violence have skyrocketed across multiple countries.

In the western Sahel, the number of reported fatalities from political violence was higher over the first half of 2019 than during any full year since 2012. Conflict is also expanding in scope, particularly into the periphery where Sahelian states struggle to maintain order. The use of communal militias by the government to reach these peripheral areas has continued to exacerbate tensions. Mass atrocities and indiscriminate violence have been used by both the government and non-state groups. As a result, intercommunal violence in particular increased in 2019. In Mali, intercommunal violence replaced attacks by Islamist militants as the deadliest form of violence targeting civilians, particularly due to targeting of Fulani and Dogon communities in the Mopti region. There were also increased attacks targeting the Christian communities in Burkina Faso, and Chad also saw deadly intercommunal violence, in particular between farmer and pastoralist communities.

Islamist violence continues to expand as well, however. Jama’ah Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) remains a deadly force in the region, and in 2019 has instigated a campaign of complex attacks across Mali. These attacks are some of the deadliest since the beginning of the crisis in 2012. In Niger, meanwhile, the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) re-established communications with Islamic State central: a development that has translated into increased violence on the ground – particularly targeting Nigerien forces. The group has substantially increased its capacities and has expanded its operations geographically while increasing its reliance on IEDs and landmines in the country to an unprecedented level. In Chad, there have been increased attacks by Boko Haram and Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP).

In particular, militant violence has increased exponentially across Burkina Faso – the number of attacks in 2019 has surpassed the total for 2018. Superficial short-term gains were made by the military in the east of the country. While the campaign caused militants to temporarily withdraw, it simultaneously resulted in an increase in attacks across other regions of the country – specifically in the Centre-Nord region, a new front in the conflict. Reported civilian deaths are so far four times the total number recorded in 2018 in Burkina Faso. However, it is not only conflict events that are increasing in the country and across the region. Throughout the central Sahel, demonstration events too have increased. Halfway through 2019, protests and riot events are at nearly the number reached in all of 2018.

As 2019 continues, disorder across the Sahel – in the form of communal violence, insurgency, and demonstrations – continues to spread and evolve. As public discontent grows with government responses to the violence, governments in the region become increasingly destabilized. As such, the latter half of 2019 will likely sustain increased disorder across multiple fronts.

Further reading:

Explosive Developments: The Growing Threat of IEDs in Western Niger

Democracy Delayed: Parliamentary Elections and Insecurity in Mali

A Vicious Cycle: The Reactionary Nature of Militant Attacks in Burkina Faso and Mali

Heeding the Call: Sahelian militants answer Islamic State leader al-Baghdadi’s call to arms with a series of attacks in Niger

No Home Field Advantage: The Expansion of Boko Haram’s Activity Outside of Nigeria in 2019

PRESS RELEASE: Political Violence Skyrockets in the Sahel According to Latest ACLED Data

Taking Stock: Disorder ahead of Nigeria’s General Election

JNIM: A Rising Threat to Stability in the Sahel

The New Normal: Continuity and Boko Haram’s Violence in North East Nigeria

Insecurity in Southwestern Burkina Faso in the Context of an Expanding Insurgency

Neighbors in Arms: Intercommunal Violence and Targeting of Civilians in Mali in 2018

Yemen: Most likely to induce 2019’s worst humanitarian crisis

In 2019, Yemen’s civil war continues unabated. A ceasefire in Hodeidah in 2018 significantly reduced the number of reported fatalities in Hodeidah, though did little to effectively build confidence between the warring parties — and no further ceasefires have followed. Though the agreement resulted in fewer reported fatalities in that province, other aspects of the ceasefire have yet to be realized. The partition of responsibilities over port control and city control is still not clearly delineated, while prisoner exchange is also still pending. The ceasefire remains fragile (Arab Weekly, 17 March 2019).

Elsewhere in Yemen, reported fatalities continue to mount at a pace equal to that of 2018. Throughout Yemen the number of reported fatalities remains constant and high, and in fact the number of reported fatalities has increased in Taizz, Ad Dali and Hajjah. Foreign military presence remains a constant in the Yemeni Civil War, though the Saudi-led coalition has faced challenges in 2019. When the Emirati military under the Saudi-led coalition Operation Restoring Hope withdrew some of their forces from Marib, Aden and the western coast, there were reports of Saudi forces being moved in to replace them in some of these areas (New York Times, 11 July, 2019). The Saudi-led coalition was also threatened by increasing opposition to American assistance for Saudi-led operations in the aftermath of the killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

Meanwhile, there has been a noted uptick in Houthi capabilities, which will likely intensify political violence along the Saudi border as 2019 continues. Houthi drone attacks on Saudi Arabia’s southern regional airports have increased drastically as part of an offensive targeting Saudi Arabian capabilities near the Saudi-Yemeni border. In this context, the first reports of Houthi cruise missile usage on two different targets emerged in June 2019. This increase in capabilities can be expected to further aggravate the conflict between the Houthis and Saudi Arabia, which has led to continuous clashes along the border regions during the last 4 years.

In southern provinces as well, there has been an increasing number of contentious ‘hotspots.’ In the first half of 2019, confrontations between pro-Southern Transitional Council (STC) forces and forces belonging to the internationally-recognized government of President Hadi have increased. Such confrontations – largely in the form of small-scale skirmishes — have occurred throughout the region, in Aden province, and increasingly in Shabwah and Hadramawt provinces, but also — a first in 2019 — in Mahrah province and on Socotra island.

The civil war in Yemen consists of multiple overlapping conflicts, with multiple domestic and foreign actors with competing interests and divergent capabilities. As fighting intensifies on multiple fronts, the hope of replicating the ceasefire in Hodeidah elsewhere in the country dims.

Further reading:

Yemen Snapshots: 2015-2019

PRESS RELEASE: Yemen War Death Toll Exceeds 90,000 According to new ACLED data for 2015

Yemen’s Fractured South: Socotra and Mahrah

Yemen’s Fractured South: Shabwah and Hadramawt

Increasing Tribal Resistance to Houthi Rule

How Houthi-planted mines are killing civilians in Yemen

Yemen’s Urban Battlegrounds: Violence and Politics in Sana’a, Aden, Ta’izz and Hodeidah

Targeting Islamists: Assassinations in South Yemen

ACLED Methodology and Coding Decisions around the Yemen Civil War

Afghanistan: Most likely to suffer from international geopolitics

New rounds of negotiations and familiar conflict patterns alike have characterized political violence in Afghanistan in 2019. Two major players in Afghanistan – the Taliban and the United States – have continued to engage in peace negotiations that began in 2018. The Afghan government is not involved in these negotiations since the Taliban has stipulated that there be an agreement about the withdrawal of foreign forces before it would be willing to negotiate directly with the central government (The Atlantic, 12 February 2019). While no concrete agreement has resulted from these talks, reports suggest July negotiations were unusually productive (ABC News, 6 July 2019). U.S. military forces have reportedly expressed their willingness to leave Afghanistan: a major Taliban demand – and a major potential shift for the nearly 20-year-old conflict.

These talks have, however, caused tensions between the Afghan government and the U.S. (The Washington Post, 14 March 2019), and despite their success, violence continues relatively unabated throughout the country. The talks were an impetus for continued Taliban attacks against Afghan and NATO forces, which included attacks strategically planned to correspond with high-profile meetings with the U.S. The Taliban attacked a joint Afghan-US military installation, Camp Shorabak, in late February – an attack which reportedly killed at least 23 Afghan soldiers. Additionally, Taliban reportedly killed a U.S. soldier in July. This latter incident has the potential to impact the Taliban’s negotiations with the U.S. The number of U.S. soldiers killed in clashes during 2019 has risen to 10 (ABC News, 14 July 2019).

Despite these new developments, violence continues to develop in 2019 along familiar lines. June and July featured a spike in clashes between the Taliban and Afghan military forces as part of the Taliban’s annual spring offensive. The Taliban continues to attempt to take hold of territory throughout the country, while the Afghan military attempts to regain territory previously seized by the Taliban. The Afghan military has seen relative success in this venture of late: in May and June of 2019, Afghan forces gained control of several districts in Ghazni and Faryab provinces, taking back control they had lost to the Taliban in 2018. Despite government gains in 2019, the Taliban has seen its own successes. The Taliban seized Qush Tepa district of Jowzjan province in early July, furthering its presence across the province and across Northern Afghanistan more broadly. Currently, the group controls three districts in the province, and is actively contesting five – meaning they are actively present in the majority of the 11 districts across the province (Long War Journal, 2 July 2019). The Taliban has also made minor territorial gains elsewhere in the country, largely of negligible strategic value.

Afghanistan’s other major security threat, the Islamic State (IS), has continued its attacks into 2019. Over the first half of the year, IS has clashed with Taliban and Afghan security forces in Kunar, Nangahar, and Kabul provinces. In two high profile attacks, IS killed 11 civilians in an attack in Kabul in March, and further civilian fatalities resulted from an attack on Afghan security forces in Jalalabad City in June. This security threat, coupled with the insecurity of a potential U.S. withdrawal, means Afghanistan will likely continue to destabilize throughout 2019.

Further reading:

War of Attrition: A New Year of Violence in Afghanistan

Eastern Afghanistan: A Tale of Two Provinces

Fighting Bullets with Ballots: Afghanistan’s Chaotic Election

ACLED Methodology and Coding Decisions around the Conflict in Afghanistan

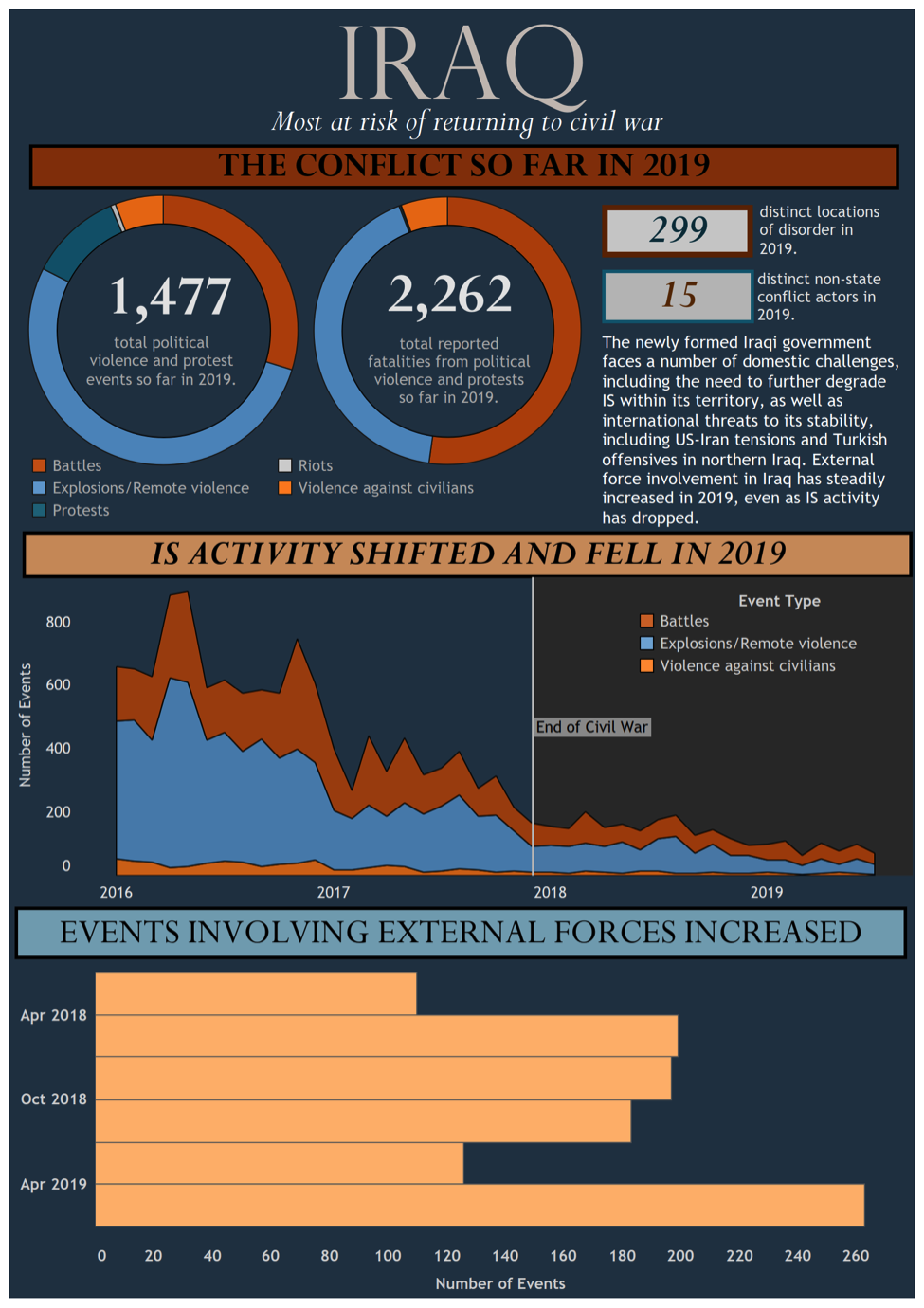

Iraq: Most at risk of returning to civil war

More than a year after the territorial defeat of the Islamic States (IS), Iraq is faced with a variety of post-conflict governance challenges. The formation of a nearly complete Iraqi government in July is a major political development for the country; this unified central government is now in a position to design and implement policy for post-conflict redevelopment (The Atlantic Council, July 1, 2019). Delays in this process, however, have resulted in a number of protests by Iraqi citizens, particularly regarding the lack of service provisions and high levels of unemployment in the country.

At the same time that the Iraqi government is struggling to care for more than a million displaced people and to rebuild its economy, IS has sought to adapt its tactics to survive in the current security environment. In 2019 thus far, IS has been active in remote, rugged terrain, mainly in the deserts of Anbar and Nineveh provinces, and the mountains that straddle Kirkuk, Salahuddin and Diyala provinces. The attacks that IS has engaged in throughout 2019 thus far seem targeted to undermine the government’s redevelopment efforts and aggravate social tensions. IS engages in violence targeting tribal leaders, politicians, village heads, and government employees, in a variety of locations, in addition to a number of incidents of arson in Kirkuk aimed at inflaming tensions between Arab and Kurdish communities.

In response to this violence, the Iraqi government launched “Operation Will of Victory” in early July. This joint operation includes the Iraqi armed forces, Popular Mobilization forces (PMF), Tribal Mobilization Forces (TMF), and U.S.-led Coalition warplanes. It remains to be seen how effective this campaign will be at dislodging IS from its remaining hold-outs.

Another challenge the Iraqi government faces in 2019 is the implication of the Turkish offensives “Operation Claw” and “Operation Claw-2” which targeted the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in Northern Iraq. These offensives, the latter of which is ongoing, not only entail a foreign military conducting operations within Iraq’s borders, but have also resulted in the evacuation of several Kurdish villages and the displacement of residents. The first phase of “Operation Claw” took place roughly a month after a four-year political agreement between the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) was signed. The agreement was a significant step towards a more stable Iraqi Kurdistan and laid the foundation for the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG).

Rising tension between Iran and the United States also presents an external phenomenon that threatens domestic stability in Iraq. Not only would such a conflict involve a contentious political decision about whether to lend support to the effort (and if so, how much and in what form), but also war between the United States and Iran would have significant negative spill-over effects into Iraq.

As 2019 progresses, the Iraqi state is in a precarious situation internally as sectarian tensions are aggravated by the presence and reach of the Iranian backed PMF, along with Kurdish-Arab tensions, and many protests calling for the Iraqi government’s engagement in redevelopment efforts and good governance. Externally, the state’s sovereignty and stability are in a state of constant distress due to interference from Turkey and Iran, and the possibility of a US-Iran war. In regards to IS, they currently represent a much less potent direct threat to the Iraqi state; however, the country’s stability will largely depend on the Iraqi government’s ability to face these domestic and international challenges, to ensure that neither an Iraqi civil war nor an IS resurgence are in the cards for the future Iraqi state.

Further reading:

Behind Frenemy Lines: Uneasy Alliances against IS in Iraq

Special Focus on Coalition Forces in the Middle East: The Global Coalition Against Daesh in Iraq and Syria

The Reconstitution of the Islamic State’s Insurgency in Central Iraq

IS Underground: The Post-War Threat to Iraqi Civilians

Unrest in Basra Signals Growing Crisis

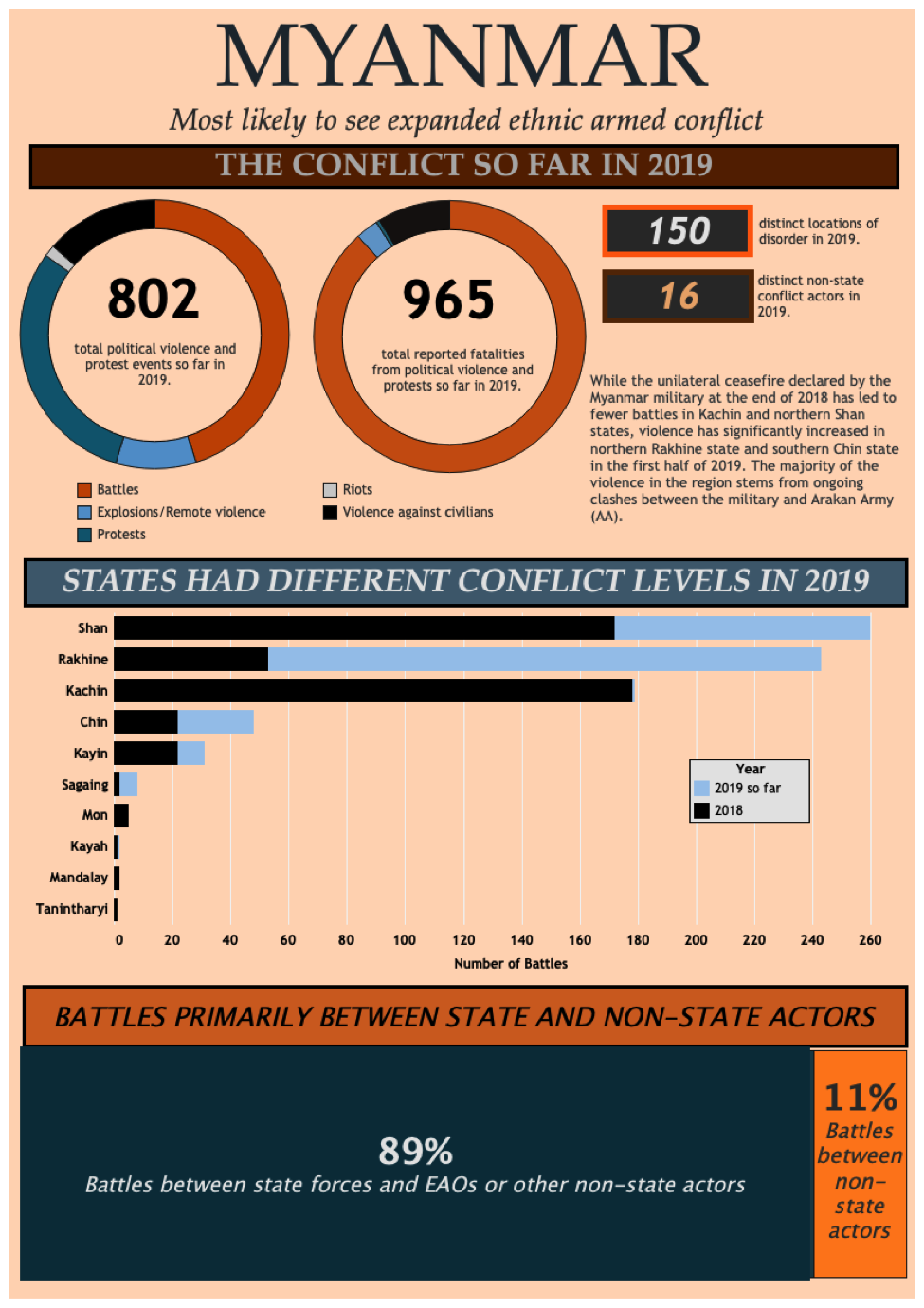

Myanmar: Most likely to see expanded ethnic armed conflict

The unilateral ceasefire declared by Myanmar’s military at the end of 2018 raised hopes that violence between the military and ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) would decline in the country in 2019. While fighting has declined in Kachin and northern Shan states relative to the same period in 2018, clashes have still been recorded during the ceasefire period between the military and various EAOs in the region. Though the ceasefire has been extended through the end of August, the declaration’s limited geographic scope hamstrings efforts to negotiate peace.

The military’s unilateral ceasefire does not include northern Rakhine and southern Chin states where fighting between the Myanmar military and the Arakan Army (AA), an ethnic Rakhine armed group attempting to establish a base in Rakhine state, has been on the rise since the start of the year. Civilians have been impacted by the ongoing fighting — 21% of the violence in Rakhine state and 19% of the violence in Chin state this year has been directed at civilians — and several Rakhine villagers have died while in military custody. The government-imposed internet blackout in several townships in the area has sparked fears that greater abuses against civilians may be happening yet are not being reported (New York Times, 2 July 2019). By designating the AA as “terrorists” and charging the leaders under counter-terrorism laws (Radio Free Asia, 8 July 2019), progress in peace talks between the two sides remains unlikely and there is a high likelihood of a protracted conflict.

In addition to continued violence between the army and EAOs, at the beginning of the year there was a spike in battles between two ethnic Shan armed groups: the Restoration Council of Shan State/Shan State Army-South [RCSS/SSA-S] and Shan State Progress Party/Shan State Army-North [SSPP/SSA-N], in northern Shan state. Such violence reached a peak in March, when there were 11 clashes recorded between the two groups, before a ceasefire was brokered. Despite the appeals to ethnic unity among the Shan, the exclusion of the Palaung State Liberation Front/Ta’ang National Liberation Army (PSLF/TNLA), an ethnic Palaung/Ta’ang armed group, means that intra-ethnic conflict is likely to remain an ongoing issue in northern Shan state.

The second half of 2019 is likely to see ongoing fighting between the military and AA in northern Rakhine and southern Chin states. As the military continues its efforts to have all EAOs sign the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA), there is likely to be continued resistance by allied groups who believe the NCA fails to adequately address the central issues of ethnic equality and self-determination. Myanmar’s many ethnic armed conflicts are likely to remain a challenge as the country prepares for the 2020 elections.

Further reading:

Improving ACLED’s Myanmar Protest Data: 2010-2019

Ceasefires and Conflict Dynamics in Myanmar

Myanmar’s Changing Conflict Landscape

Myanmar: Peace Talks Belied by Ongoing Conflict in Rakhine and Chin States

Demonstrations in Myanmar

Understanding Inter-Ethnic Conflict in Myanmar

Analysis of the FPNCC/Northern Alliance and Myanmar Conflict Dynamics

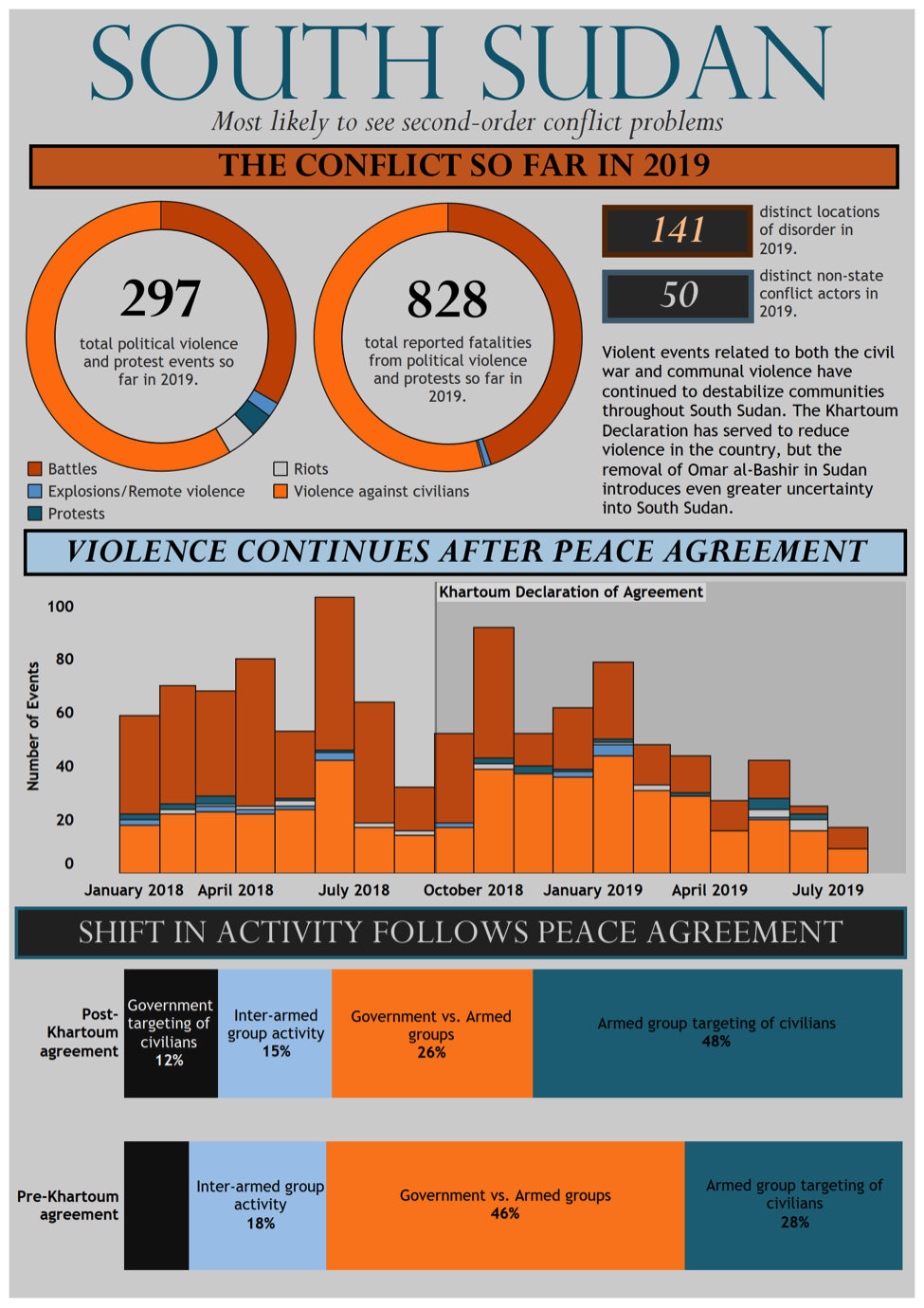

South Sudan: Most likely to see second-order conflict problems

In 2019 thus far, violence in South Sudan has been marked by two trends: violence between dissident military commanders and state forces and their paramilitary allies, and persistent communal violence.

One of the most notable trends associated with the civil war in 2019 has been the intensive counter-insurgency campaign in parts of the former Central Equatoria. This violence involves fighting among the National Salvation Front (NAS), government forces (including the military and intelligence services), and associated paramilitary forces. This conflict is accompanied by violence targeting civilians by belligerents on both sides of the civil war and their respective militias. Yei, in particular, continues to be a hotspot for such violence. This violence is likely under-reported, as organizations like Human Rights Watch and UNMISS are some of the only outlets to circumvent the effective media blackout in the region (Amnesty International, 18 July 2019). Since the start of the rainy season in May, violent events associated with that campaign have declined dramatically; however, the potential for such violence to return will loom over the dry season set to begin at the end of the year.

Communal violence has been particularly concentrated in areas around Wau (particularly Kuajina county), and across the disputed Tonj, Gok, and Northern Liech states. Elsewhere in the country, raiding and ambushes persist across parts of the former Lakes state, in and around the disputed Boma state, and parts of the former Western Equatoria and Upper Nile states. Communal violence is sometimes driven by grievances over access to resources impacting livelihoods (particularly grazing rights), though there have also been reports of political and military elite using communal militias as proxy forces to advance their own interests (Ceasefire and Transitional Security Arrangements Monitoring Mechanism, July 2019). Communal violence in 2019 thus far has been particularly lethal and destructive; instances of inter-communal violence in South Sudan has been associated with more than 6 reported fatalities per event thus far this year, and events in which communal militias target civilians have been associated with more than 5 reported fatalities per event.

The combination of these two conflicts is reminiscent of the period between the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2005 and the eve of the civil war in late 2013. The violence of the past few months suggests the Revitalised Agreement on the Resolution of Conflict in South Sudan (R-ARCSS) will not put an end to the violence, even if the risk of large-scale violence between the government and various factions of the SPLM-IO rebellion has diminished. Events in Sudan may prolong the political limbo that the country is in; the removal of Bashir from the office of the Presidency in Sudan, who was instrumental in the negotiation of the R-ARCSS, brings into question the durability of this arrangement (E-IR, May 26, 2019). The uncertainty of the future economic relationship between Sudan and South Sudan (as well as close linkages across security services) introduces yet another potential source of instability into the latter.

The remainder of 2019 will likely see the parties to the civil war grapple with the domestic implications of developments to their north, while communal violence continues. Both of these sources of violence require durable political settlements that do not appear to be forthcoming.

Further reading:

South Sudan: This War is Not Over

Conflict Activity in South Sudan

The Many Sides of International Peacekeeping in Africa

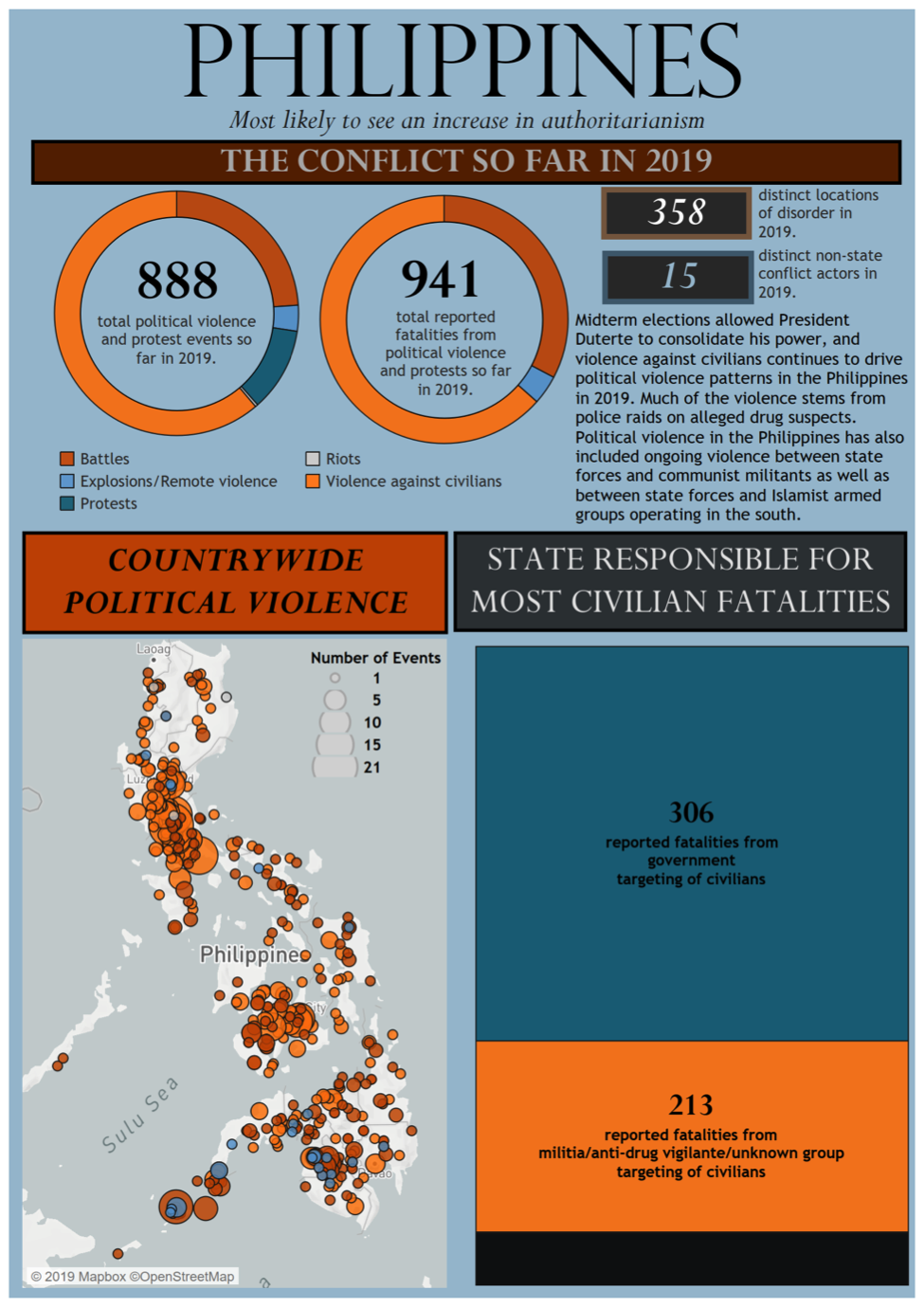

Philippines: Most likely to see an increase in authoritarianism

The election in the Philippines in May of politicians allied with President Duterte has allowed Duterte to further consolidate his power this year (The Diplomat, 22 May 2019). While there was a spike in protest events in May around the elections, and a number of protests accompanied Duterte’s recent State of the Nation speech, the midterm elections have enabled Duterte to continue pursuing his political agenda with little challenge.

A key part of Duterte’s agenda has been the “War on Drugs” in which extrajudicial killings of alleged drug suspects have been ongoing. Many victims of the crackdown on drug suspects have been wrongly accused. Further, a growing number of government officials and politicians have found themselves labelled as involved in illegal drugs in an effort by Duterte to silence opposition against him (New York Times, 22 July 2019).

Violence against civilians has also extended outside of the targeting of drug suspects as many activists and groups labelled as leftists continue to be targeted in a practice known as ‘red-tagging’ (Amnesty International, 24 June 2019). As a result of this practice, several activists have been killed since the beginning of 2019 (Human Rights Watch, 18 June 2019). In the same vein, a number of farmers in the Philippines have been targeted and killed after being accused of supporting the communist armed group, the New People’s Army (NPA) (Foreign Policy, 10 June 2019).

Battles between the Philippine armed forces and the NPA reached a high early in the year – from March to May — before declining again in June. The government’s approach to the NPA has recently shifted from peace talks with the whole group to localized talks in various regions throughout the country in an effort to decrease the numbers and strength of the NPA in the absence of a larger peace agreement (The Interpreter, 27 May 2019). This year marks the 50th year of the formation of the NPA; conflict between the group and Philippine state forces continues to pose a threat to peace in the Philippines.

Peace in the Philippines has also been threatened by the ongoing violence in the country’s south where both separatist and Islamist armed groups have operated over the years. At the beginning of the year, a plebiscite led to the ratification of the Bangsamoro Organic Law which created the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM). While the establishment of the BARMM has largely helped to end the conflict with the separatist Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), conflict with Islamist armed groups continues in the region where martial law has been extended until the end of 2019 (Reuters, 12 December 2018). In particular, fighting between the Philippine military and the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) in BARMM reached a peak in March and April this year.

As 2019 continues, there is likely to be continued fighting between Philippine state forces and the armed groups in the Bangsamoro region as well as between Philippine state forces and the NPA. Further, Duterte’s consolidation of power will allow him to continue prosecuting his “War on Drugs” resulting in the continued targeting of civilians in the country.

Further reading:

PRESS RELEASE: Data Confirm Wave of Targeted Attacks in the Philippines

Midterm Elections in the Philippines: Power Consolidation at Its Finest

Drug War Data: Improving Coverage of the Philippines

“Ninja” Cops: Duterte’s War on Police Linked to Illegal Drugs in the Philippines

Duterte’s War: Drug-Related Violence in the Philippines

ACLED Methodology and Coding Decisions around the Philippines Drug War

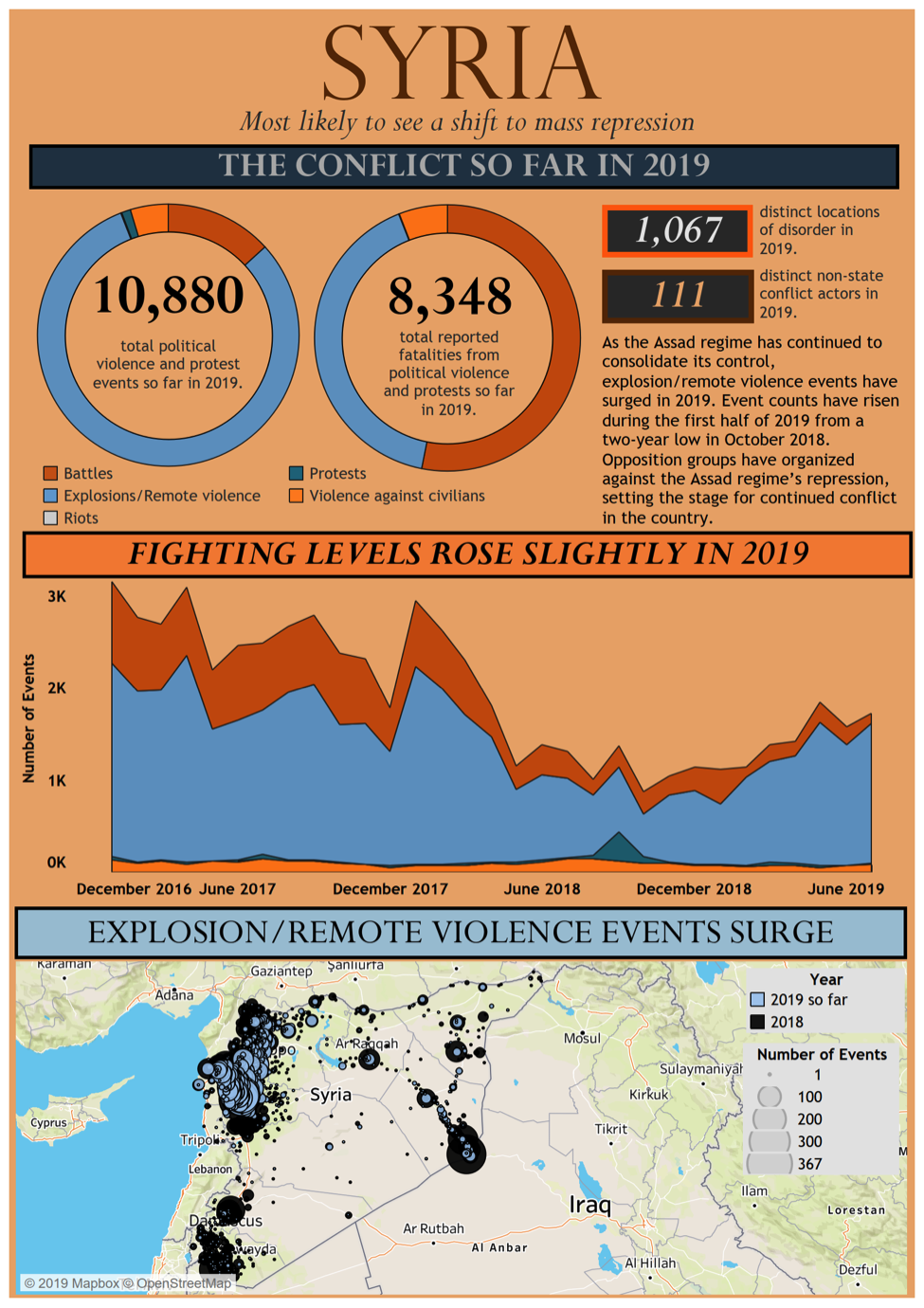

Syria: Most likely to see a shift to mass repression

Violent conflict in Syria in 2019 thus far remains dominated by the conflict between the Assad regime and a variety of non-state armed groups, including Salafi-jihadist rebel groups and anti-regime militias.

Explosion/remote violence events have been the most common type of violence in Syria in 2019 thus far; there was an uptick in the number of such events between April and May. Regime shelling in the greater Idleb area is part of the reason for this increase; there have been more than 6,000 explosion/remote violence events reported in 2019 thus far and regime forces are responsible for approximately 74% of these events.

Another significant shift in the nature of conflict in Syria comes from Islamic State (IS) regrouping and shifting tactics. In March, Syrian Democratic Forces (QSD) and Coalition forces managed to take control of IS’ last enclave on the eastern bank of the Euphrates river, relegating IS to a few remaining pockets in the desert (BBC, March 23, 2019). Lacking significant territorial control, IS has relied on asymmetric attacks thus far this year to continue its campaign against QSD and the regime. This development has shifted the characteristics of conflict in the country. IS rebels have also continued their covert operatives active in regime- , rebel- , and QSD-controlled territories across Syria. Concurrent with regime efforts to further degrade IS elsewhere, Hayat Tahrir al Sham (HTS), another rebel group, has continued its process of cementing and institutionalizing control in Idleb (BBC, February 26, 2019).

The Assad regime has also continued to consolidate power throughout southern Syria in 2019 thus far. This effort has been accompanied by a significant crackdown on civilians and former opposition elements. This repression has been counter-productive, prompting resistance from rebel groups opposed to the government, such as Dar’a Popular Resistance, and unidentified or anonymous armed groups likely to be part of Dar’a Popular Resistance. Since the start of the year, there have been more than 57 events involving opposition rebels. Throughout the course of the year, events involving these groups have shifted towards a greater reliance on explosions and remote violence. Activity involving these groups is concentrated in Dar’a in southern Syria.

It seems likely that the Assad regime will double-down on this strategy of repression. The result will likely be an intensification of the patterns of violence that have developed in 2019 thus far: violent contestation over territorial influence and a surge in anti-regime activity by armed groups.

Further reading:

Counter-punch: Syrian opposition pushes back against regime offensive in Northwest Syria

The State of Syria

PRESS RELEASE: ACLED Integrates New Partner Data on the War in Syria

PRESS RELEASE: Even as Overall Violence Drops, Civilians Face Record Threats in Syria

Syria’s Demilitarized Zone: Regime Escalation

Islamic State Underground in Syria

The Risks of Reconciliation: Civilians and Former Fighters face Continued Threats in Syria

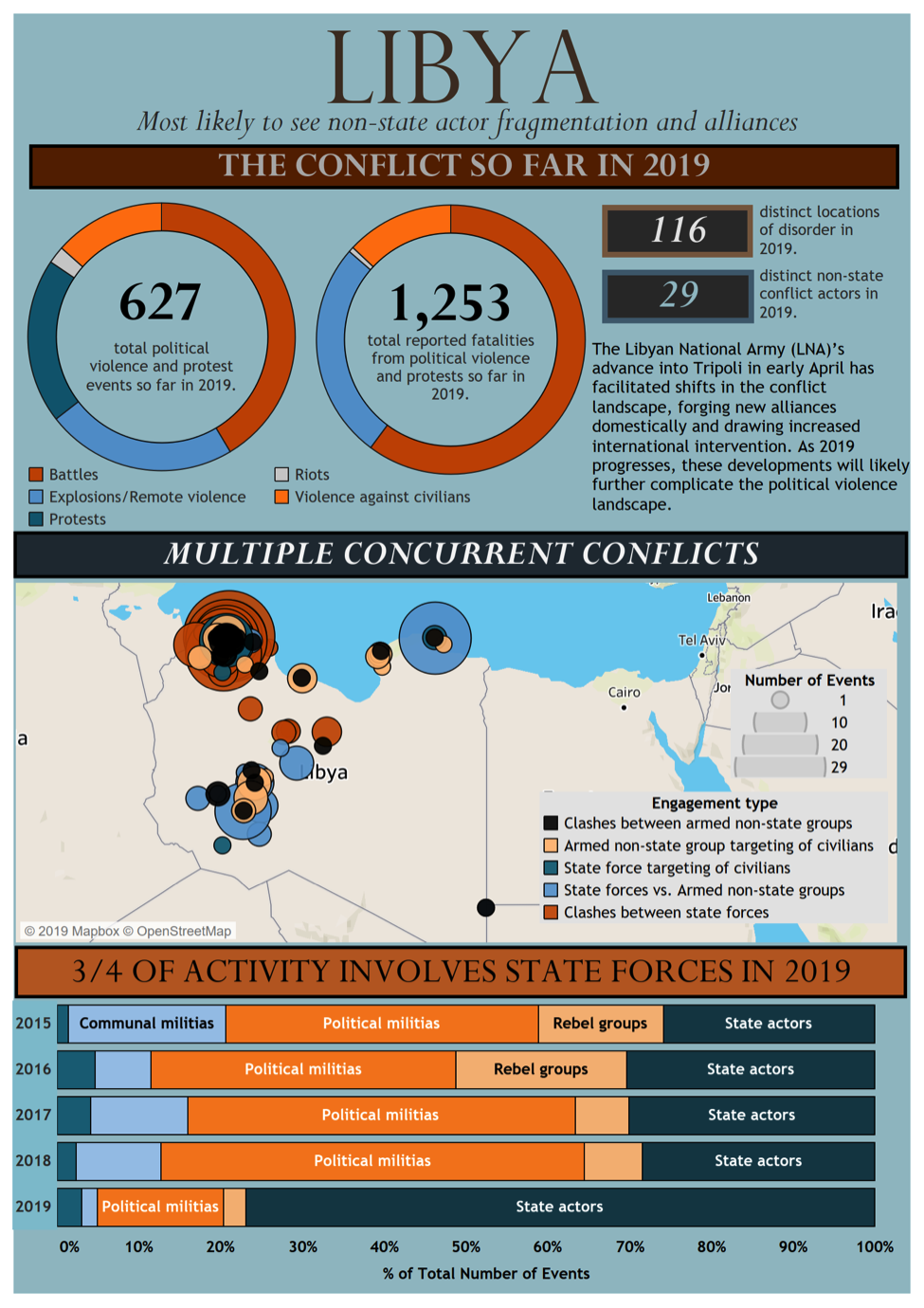

Libya: Most likely to see non-state armed group fragmentation and alliances

Libya’s civil war remains ongoing in 2019, with little sign of a peaceful resolution in the near future. One of the most notable trends in the country in 2019 has been the advance of the Libyan National Army (LNA), an armed faction under the command of Field Marshall Khalifa Haftar. The LNA has built upon the success it enjoyed in 2018, expanding its presence and influence in southern Libya since mid-January. The faction has cemented its gains through a combined approach of coercion, co-optation, and local arrangement. For example, the LNA initially clashed with Tuareg militiamen in Ubari and around the Sharara Oilfield; however, eventually, a number of local Tuareg brigades joined the LNA to maintain control of the area (Middle East Eye, February 10, 2019). The durability of these local arrangements remains in question and the LNA has engaged in minimal efforts to govern the territory that it controls.

One of the most defining events in Libya thus far this year is the large offensive on Tripoli, the capital, launched by the LNA in early April. The lack of a unanimous statement from the international community condemning this offensive ultimately served to intensify the conflict. Haftar was emboldened by the lack of a coordinated response, while Turkey felt compelled to provide the Government of National Accord (GNA) with substantial material support, including armoured vehicles and drones. Not only did this further internationalize this conflict, it also affects what types of violence are used. The result has been an escalation of the air war in the country; thus far in 2019, nearly 21% of events in Tripoli have been air/drone strike events and an additional 18% have been shelling/artillery/missile attack events.

Haftar’s offensive on Tripoli has also created conditions in which the Islamic State in central and southern Libya could escalate their violent activity. The rebels were capable of carrying out a twin car-bombing attack — a rare style of attack in this conflict — in Derna in June. This attack suggests that the gains made in the Battle of Derna in 2018, in which the LNA defeated a variety of Islamist armed groups, have been degraded by the LNA’s efforts to take Tripoli.

The Tripoli offensive appears to have unified a number of smaller, local armed groups against the LNA. In some instances, the mutual threat posed by the LNA’s offensive united former rivals; this was the case when militias based in Tripoli allied with the major Misrata militias, despite having been bitter rivals prior to Haftar’s offensive. It remains to be seen whether the alliances against the LNA will be sufficient to counter Haftar’s offense (DW, April 5, 2019). Though many groups have joined the Tripoli battle, others have reserved their assets — in the hopes that doing so will put them in a position to exercise influence in a post-Tripoli scenario.

As 2019 progresses, the long-standing tensions between east and west will continue to exacerbate a security vacuum in the country’s center and south. The clearest characteristic of the ongoing fight for control of Tripoli is the humanitarian cost it has levied on the civilian population — a pattern which will likely continue throughout 2019.

Further reading:

Push Comes to Shove: Haftar’s abrupt, and inevitable, march towards Tripoli

Targeting Tripoli: Newly Active Militias Targeting Capital in 2018

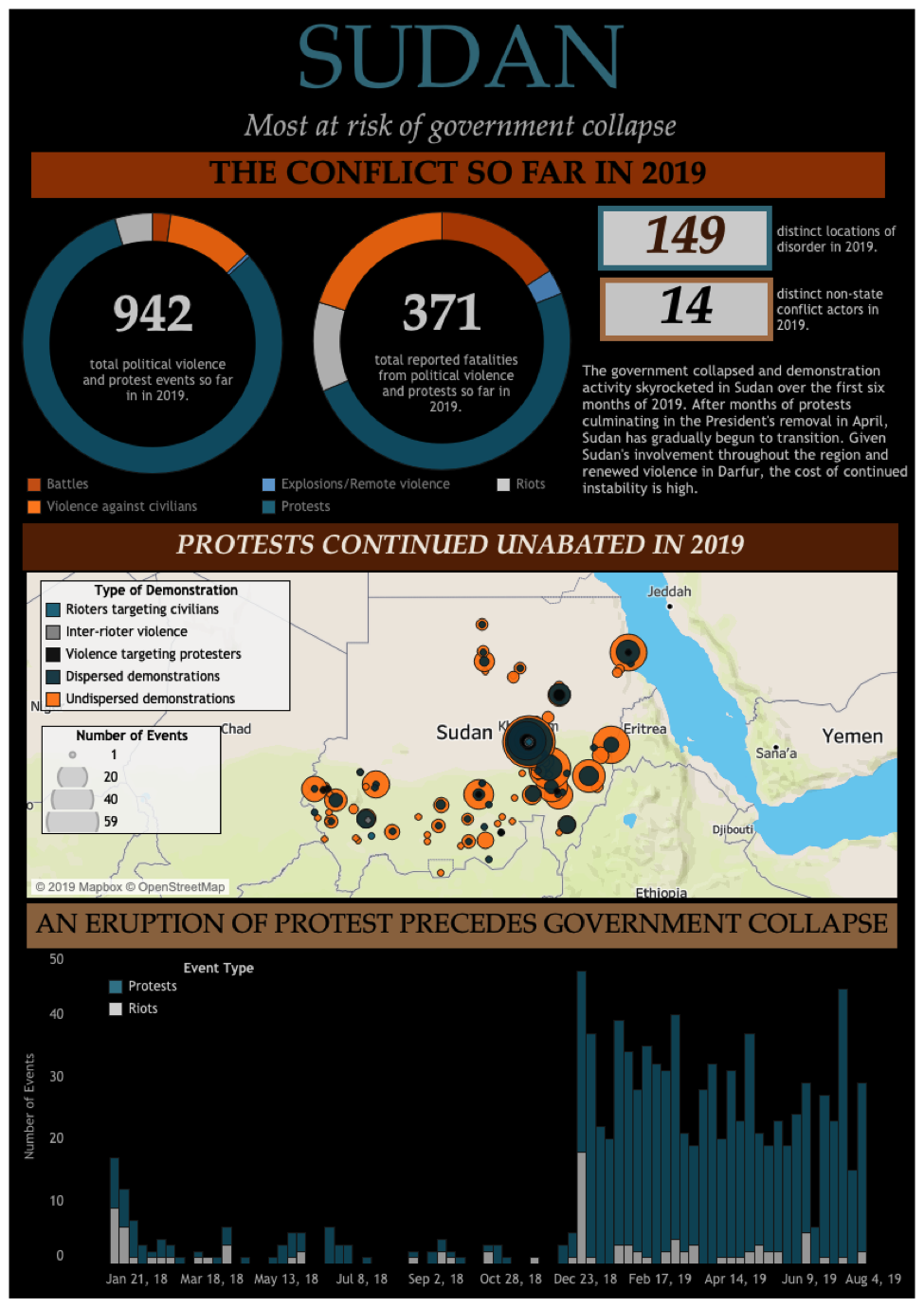

Sudan: Most at risk of government collapse

After months of protests, Sudan’s long-standing ruler President Omar al-Bashir was overthrown via a military coup in 2019, heralding a new and uncertain era for the country and the region in general. Sudan’s deep involvement in regional politics and conflicts — in the Horn of Africa, North Africa, the Sahel, and the Gulf states — underscores just how high the stakes of Sudan’s current upheaval are, both for Sudanese civilians themselves, as well as for civilians of countries in which Sudan has become enmeshed.

Large and increasingly well-organized demonstrations which erupted in late 2018 quickly assumed an anti-regime agenda. Violence against protesters was initially high, but – in what may be a sign of vulnerability on the part of Sudan’s then-president Bashir – steadily decreased. President Omar al-Bashir was ultimately deposed on April 11 in an early morning palace coup orchestrated by several senior security officials, having reportedly lost the support of several Gulf state patrons (BBC, 15 April 2019). The Transitional Military Council (TMC) (comprised of several prominent generals and security officials) did not mark a decisive break with the Bashir regime– and a dizzying pattern of appointments, resignations, and arrests followed in the immediate aftermath of the coup (Radio Dabanga, 14 May 2019). Large scale anti-government protests – organized under the auspices of the Sudanese Professionals Association, who converged with other non-regime political groups to form the Alliance for Freedom and Change (recently renamed Forces for Freedom and Change, FFC) – continued throughout this period, as did the large sit-in protest outside the Sudan Armed Forces headquarters in Khartoum, demonstrating that Bashir’s removal from power was insufficient to appease the people’s demands.

The new turn taken by Sudan is far from peaceful. On 3 June, amidst signs of a breakthrough agreement between the TMC and FFC regarding a phased transition to civilian rule, Rapid Support Forces (RSF) paramilitaries attacked protesters and civilians in the area around the sit-in, killing more than one hundred people and injuring several hundred (Al Jazeera, 27 July 2019). The Deputy Chairman of the TMC – Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (aka ‘Hemedti’) – immediately distanced himself from the attacks, and suggested alternative forces in RSF attire were responsible. Protests (and general strikes) intensified in the aftermath of the massacre, whilst African Union and Ethiopian mediators sought to broker a new agreement between the TMC and FFC.

On July 5, and under pressure from the West and allies in the Gulf, the TMC and FFC announced they had reached an agreement on a transitional government (Washington Post, 13 July 2019). The agreement centers upon a rotating presidency and a Sovereign Council comprised of mixed military and civilian members. An investigation into the Khartoum massacre was dismissed by the FFC because it implicated eight RSF officers – but no senior TMC figures, including ‘Hemedti’ – in the attack (Radio Dabanga, 29 July 2019). Since the agreement between the FFC and TMC was reached, violence has intensified in parts of Darfur. Closer focus on the peripheries may be required to ensure that events in Khartoum do not deflect attention from the troubled hinterlands of Sudan, which – despite spikes in violence – have been largely overshadowed by the momentous events in the capital. This continued instability can be expected to only spread – across the country and the region – as 2019 continues.

Further reading:

The Rapid Support Forces and the Escalation of Violence in Sudan

Backsliding: Demonstration Activity in Post-Bashir Sudan

The First Step on a Long Road: Public Demonstrations and Political Reform in Sudan

Pressure Points: Sudan’s State of Emergency and Anti-Government Demonstrations

Flour Power: Protests and Riots in Sudan in December 2018