While demonstrations are not uncommon in Iraq, the most recent wave of riots and protests – which has been ongoing since 1 October 2019 – has been unusually violent. Despite some concessions, the high reported fatality count from these demonstrations, and the clear evidence they provide of citizens’ ongoing disenchantment with the government, will continue to pose a serious threat to Iraq’s stability in the near future.

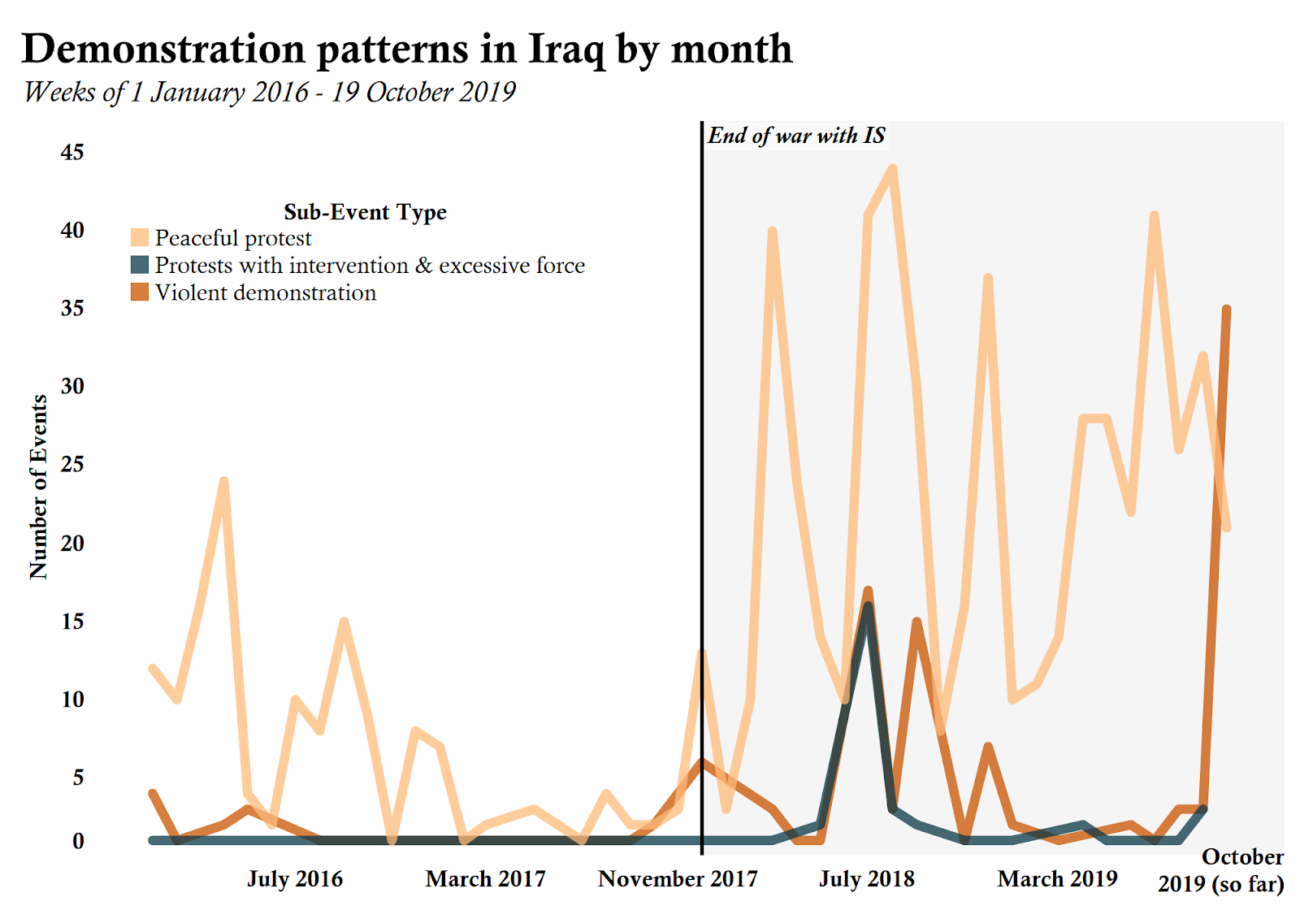

Periods of demonstrating in Iraq have occurred as recently as last year, indicating that the government’s declared victory against the Islamic State (IS) in December 2017 did not end widespread citizen discontentment with the government. In fact, demonstration levels have generally increased since December 2017 (see graph below). Facing lower levels of existential threats from groups such as IS, Iraqi citizens have increasingly taken to the streets to protest low-quality governance, insufficient service provision, and inadequately addressed corruption.

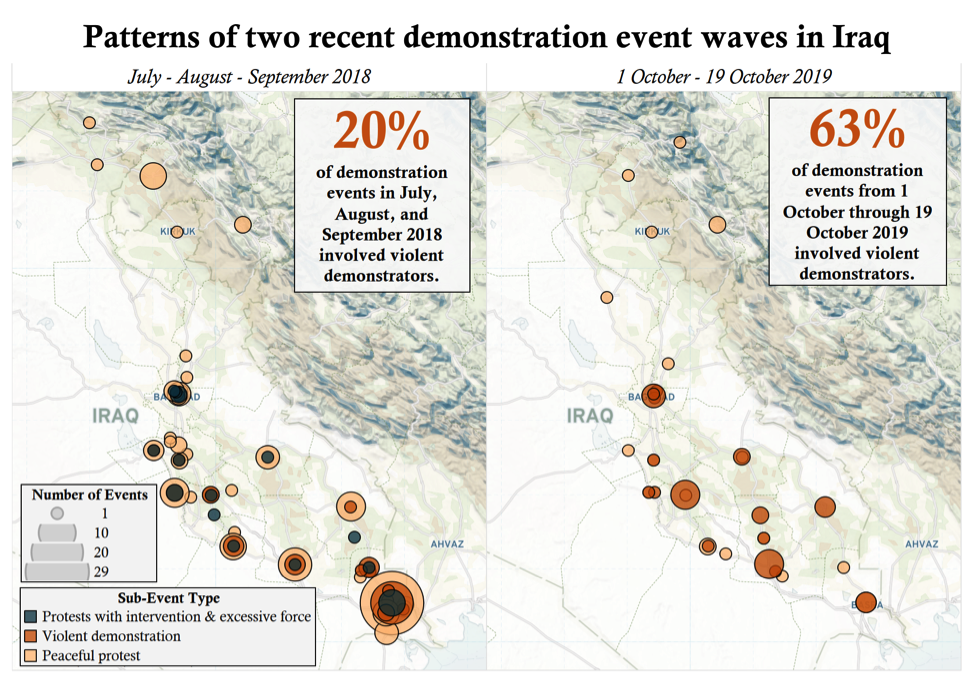

This current series of demonstrations, like other recent waves, takes aim at the inefficiency of the government in providing basic services and employment, as well as the ever-present reality of endemic corruption. Many of the demonstrations, both in 2018 and 2019, were concentrated around areas that are oil-rich, especially in the south (see map below). Southern Iraq accounts for most of Iraq’s oil production, but this has done little to lift the region out of poverty.

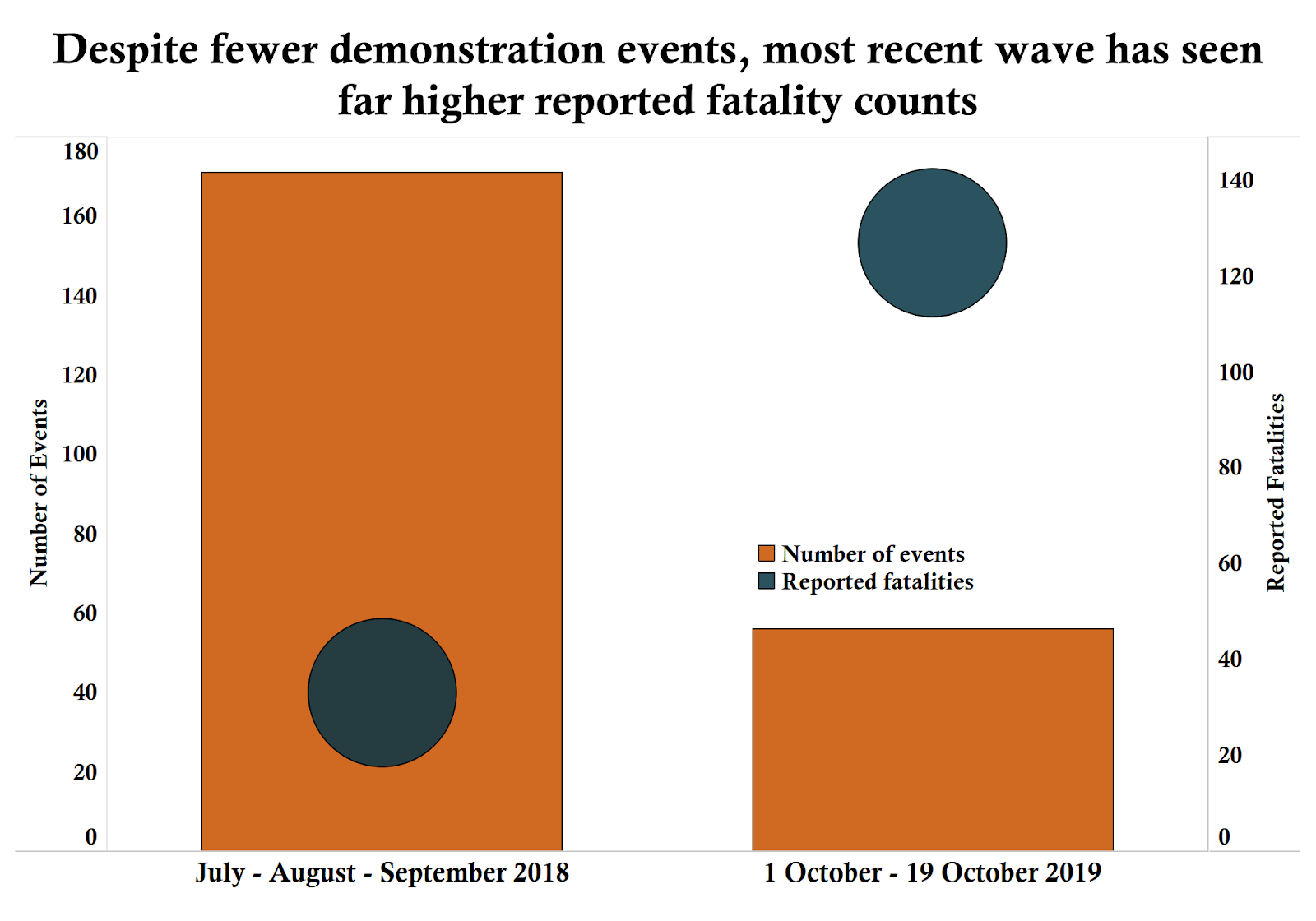

However, this recent wave of protests differs from previous demonstration waves in several crucial ways. The scale and magnitude of the recent demonstrations, as well as the extent of the use of violence by the government – more than 120 people were killed as of 19 October – is unprecedented (see graph below). Additionally, the first two weeks of October had the second-highest number of demonstration events of any full month since 2016.

The timing of these protests is also unusual. Previous demonstrations usually followed shortages of electricity and water in the torrid summer months, resulting in an explosion of popular frustration. However, due to heavy rainfall and mild summer, the provision of services improved in 2019 (BBC, 7 October 2019). In this most recent wave, the trigger is not insufficient service provision. Indeed, October’s demonstrations have been more spontaneous, more decentralized, and participants have been more independent than past demonstrators. Most of those Iraqis active in this most recent round of demonstrations are young men unaffiliated with the civic and political forces that have organized demonstrations in the past, such as the Sadrist movement, Communists, or other opposition parties (Washington Post, 6 October 2019): ACLED data demonstrate that over 90% of recent demonstration events had no links to organized associate actors. As such, these demonstrations did not result in a cohesive list of specific demands. More than anything, the recent demonstrations seem to signal the frustrations of disenchanted youth, who face challenges to their livelihoods as they are unable to find jobs in a country plagued with corruption. The heavy-handed response of the authorities has exacerbated the situation, turning some peaceful protests into violent riots (see map below).

In order to contain the demonstrations, Prime Minister Abdul-Mahdi’s cabinet issued a series of reforms early in the second week of the demonstrations, including land distributions, construction of 100,000 new housing units, military enlistment, increased welfare stipends for needy families, and the creation of large market complexes (Middle East Online, 9 October 2019). This, in combination with a number of coercive measures – and possibly fatigue – seem to have contained the demonstrations for the time-being (Al Jazeera, 05 October 2019). But the periodic return of demonstrations since 2011, in absence of major reform, indicates that a new round of unrest is likely. Corruption remains a major problem in Iraq, which is primarily driven forward by a deeply entrenched patronage network between political parties and senior civil servants (Chatham House, 01 October 2019). In each wave of unrest, demonstrators have taken to the streets, demanding that the political system that has given rise to this endemic corruption be reformed. Unless these demands are met, Iraq will continue to be destabilized by popular alienation from the ruling elite and ensuing mass demonstrations.

Yet in the near future, the prospects for true reform in Iraq remain dim. After each round of demonstrations, the political elites have acknowledged the popular discontent and offered piecemeal concessions but failed to deliver meaningful change. It is unlikely that Prime Minister Abdul-Mahdi, a technocrat who came to power last year as a compromise candidate (The Guardian, 03 October 2019), will be able to reform the political system in any meaningful way. Even if he resigns, in absence of genuine parliamentary opposition, the system would likely reproduce itself in a new cabinet, also at the behest of the very system that needs reforming.