This is a joint brief by Kars de Bruijne and Loïc Bisson produced in partnership with the Clingendael Institute and published in the Clingendael Spectator.

The outbreak of COVID-19 has strengthened the position of states across West Africa. Governments are subtly exploiting the crisis to repress opposition and manipulate elections. The lack of genuine opposition risks fueling violent extremism throughout the region. More than ever, the EU – as West Africa’s largest trading partner – has to push for inclusive governance. It is in its self-interest.

West Africa is a region prone to high levels of political violence.1Marc, A., Verjee, N., Mogaka, S. ´The Challenge of Stability and Security in West Africa´. Africa Development Forum, World Bank, Agence Française de Développement, 2015 Violence in the region is predominantly generated by contested elections, governments becoming increasingly authoritarian, elite competition and problems with local governance. Instability is further compounded by two clusters of ‘global’ armed conflict in the Sahel and around Lake Chad.

In both clusters, global extremist groups have struck up marriages of convenience with local groups. Observers fear that extremists’ next step is to fuel local unrest in places such as northern Ghana, western Togoland, north Benin and north-west Nigeria.2 Théroux-Bénoni, L., Adam, N. ´Hard counter-terrorism lessons from the Sahel for West Africa’s coastal states`. Institute for Security Studies, 5 June 2019.

Since the onset of the pandemic, analysts have predicted that COVID-19 will significantly impact political violence and demonstration activity in the region. Some fear competition over basic needs,3Knoope, P. ´Eight reasons why COVID-19 may lead to political violence`. Clingendael Spectator, 9 April 2020. others see fewer protests and demonstrations,4Hossain, N. ´Fear of a fragile planet`. Institute of Development Studies, 8 April 2020. and yet more claim that international crisis management systems and peacekeeping missions will be handicapped, allowing armed groups to exploit the situation.5Coning, C., ´The Impact of COVID-19 on Peace Operations` IPI Global Observatory, 2 April 2020; International Crisis Group ´Contending with ISIS in the Time of Coronavirus`. 31 March 2020; Petti, M. ´Could ISIS Use the Coronavirus to Attack the West? `. The National Interest, 2 April 2020. Many believe that state authorities will use new-won powers to reassert control and conveniently address political problems.6Guterres, A. ‘We are all in this together’: Human Rights and COVID-19 Response and Recovery’. United Nations, 23 April 2020; New York Times. ‘For Autocrats, and Others, Coronavirus Is a Chance to Grab Even More Power’. 30 March 2020; OHCHR. ´COVID-19: Exceptional measures should not be cover for human rights abuses and violations – Bachelet`. 27 April 2020; France24. ´Security forces use violent tactics to enforce Africa’s coronavirus shutdowns`. 1 April 2020.

The problem is that these remain unproven hypotheses. For example, analysts warned of increased Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) activity in the Sahel,7Columbo, E., Harris, M. ´Extremist Groups Stepping up Operations during the Covid-19 Outbreak in Sub-Saharan Africa´. Center for Strategic International Studies, 1 May 2020 but in reality the region has seen a drop in ISGS attacks. Unclear violence patterns leave policymakers in the dark as to how to respond. Certainly, ‘smart responses’ that account for uncertainty are important.8Bell, C. ´COVID-19 and Violent Conflict: Responding to Predictable Unpredictability`. Just Security, 24 March 2020. But above all they need empirical evidence.

Data show an increase of COVID-19-related violence against civilians by state forces, and governments have suppressed opposition and manipulated elections

A review of available conflict data highlights that COVID-19 has strengthened the role of the West African state. The data show an increase of COVID-19-related violence against civilians by state forces. Moreover, the data reveal how governments (e.g. Guinea, Sierra Leone, Côte D’Ivoire, Togo, Benin) have used COVID-19 to alter the role of the opposition and manipulate upcoming elections.

A wildfire of opposition repression risks flaring up conflicts, as opposition is excluded from the political process. COVID-19 brings the risk of a regional spill-over of violent extremism from the Sahel to the coastal states one step closer. With the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) currently blocked, the EU and its member states have to push for inclusivity.

Excessive use of state force

The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) collects daily information on political violence and demonstrations in West Africa.9One of the authors oversees ACLED data collection in the region. These data show that, contrary to many predictions, levels of political violence in the region have not changed since the COVID-19 outbreak.

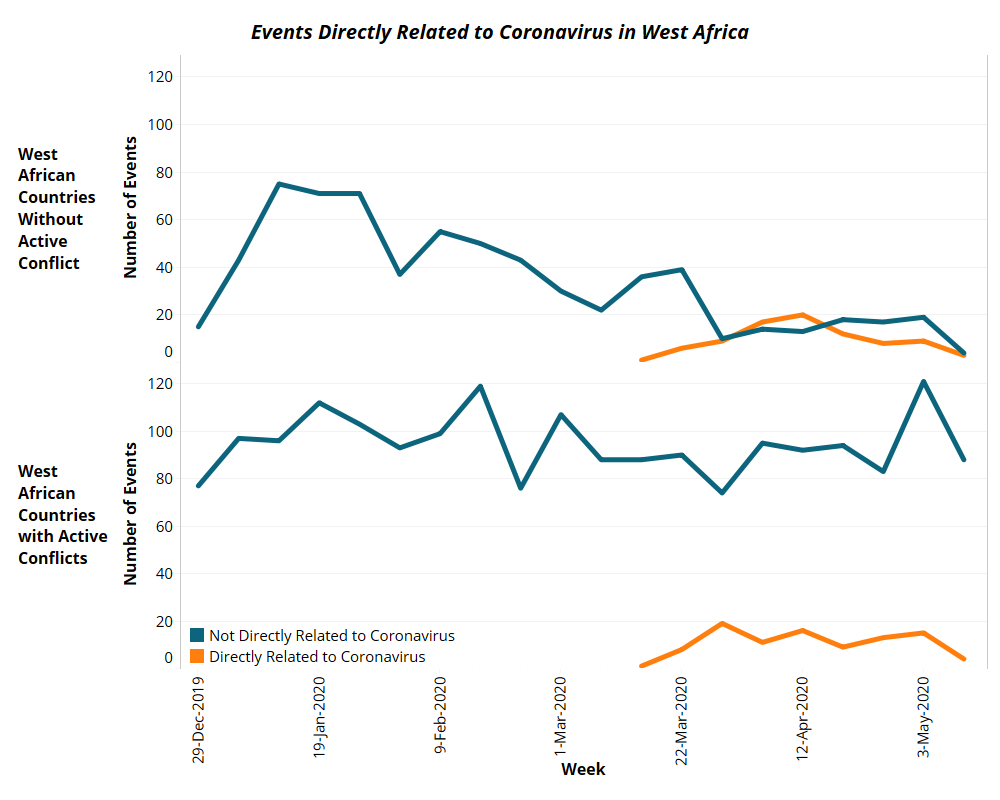

Figure 1a. Events directly related to Coronavirus in West Africa.

However, careful examination of these data highlights that the outbreak has altered the reason for violence and demonstrations. By May 2020, half of all incidents in countries without conflict involved mobilization over the coronavirus pandemic, either as government forces harshly enforced new regulations or as people rioted and protested against these very measures (see Figure 1a).10In order not to artificially increase COVID-19-related VAC, ACLED has stricter definition for inclusion for COVID VAC events – meaning that the observed effect is robust. For example, in Côte d’Ivoire multiple violent demonstrations against testing centers took place in the capital – particularly in opposition areas like Youpogon, Kumasi, and Abobo.11Claiming that the centers spread the disease and were posted deliberately in opposition areas.

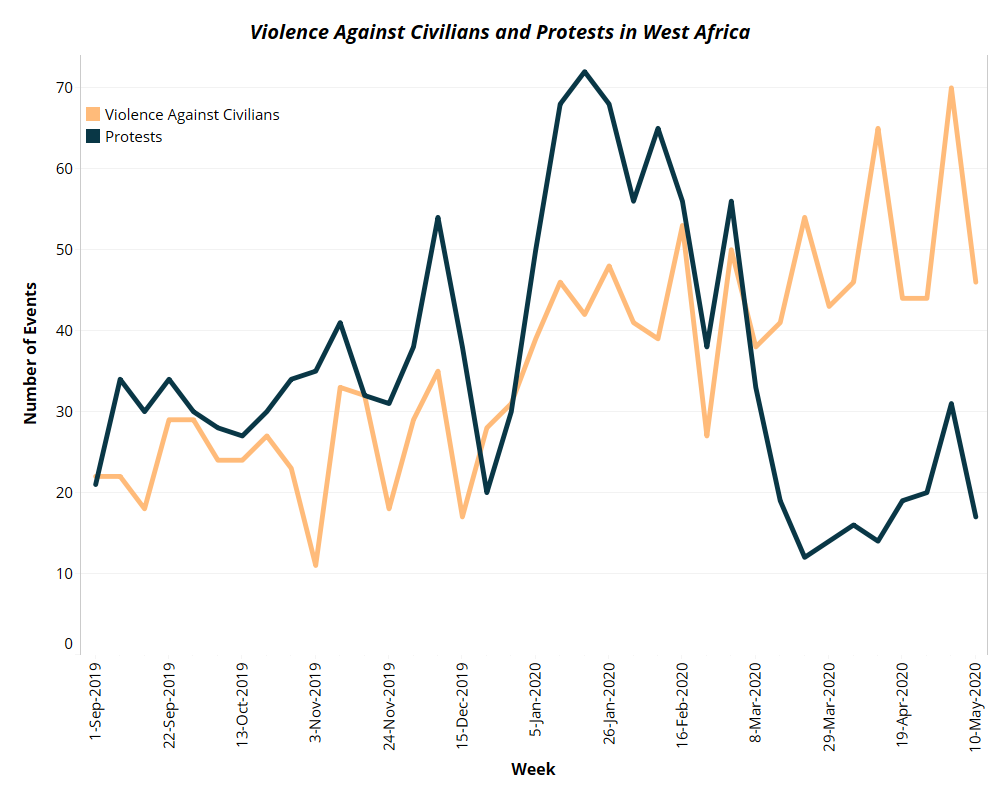

Figure 1b. Violence against civilians and protests in West Africa.

Another observation is that the type of incidents has changed. The COVID-19 outbreak has led to a drop in protests and an increase in violence against civilians (See Figure 1b). Those most responsible for this violence are government forces. Most of this violence takes place in urban areas like Abidjan, where West Africa’s generally weak governments wield influence.

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, the balance of power is changing in favor of West African governments

The balance of power is changing in favor of West African governments. By mid-April in Nigeria, more people had died of excessive policing than COVID-19.12BBC. ´Coronavirus: Security forces kill more Nigerians than Covid-19`. 16 April 2020. On March 31, eight inmates died in Kaduna during clashes with prison guards over a lack of social distancing. In early April, four traders died at a market in Kaduna after a brutal police crackdown.

COVID-19-related incidents make up nearly 20% of all political violence and protests in Nigeria and have led to 32 reported fatalities. Police brutality is also rampant in Togo, Benin and Liberia, where video clips circulate on social media of security forces beating up civilians.

The politics of COVID-19

Excessive state force is not just an accidental consequence of badly trained security personnel; there is a clear politics to these numbers.13Bisson, L., Schmauder, A., Claes, J. ´The politics of COVID-19 in the Sahel´. Clingendael Institute, May 2020. In West Africa, regime survival often depends on the loyalty of the security sector.

Politicization, unclear command and control, personalized ties and some form of freedom to handle their own affairs are purposively maintained – thus facilitating abuse.14Ouédraogo, E. ´Obstacles to Military Professionalism`. Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 31 July 2014. E.g. see also Niger’s cancellation of a UN Security Council meeting on abuses by security forces. Africa Intelligence. ´ONU : Niamey fait annuler une réunion du Conseil de sécurité sur les exactions des militaires sahéliens` 11 May 2020. COVID-19 reveals the real nature of this arrangement: The security sector enforces decisions made by a contested regime and in exchange gets away with brutality.15Runciman, D. ‘Coronavirus has not suspended politics – it has revealed the nature of power’. 27 March 2020.

State authorities in West Africa skilfully seize opportunities to solve contentious political issues

There is more politics behind the COVID-19 response. State authorities in West Africa skillfully seize opportunities to solve contentious political issues. In Sierra Leone, a one-year state of emergency that restricted the potential to mobilize conveniently coincided with the ruling of a commission of inquiry on the former regime. Opposition protests have been banned under the pretext of a health response.

In Benin and Cote d’Ivoire, authorities withdrew from specific protocols of the Cour Africaine des droits de l’homme et des Peuples.16Millecamps, M., Soumaré, M. ´Justice : quand les États tournent le dos à la Cour africaine des droits de l’homme`. Jeune Afrique, 7 May 2020. These protocols allowed individuals – like opposition leaders – to seek sub-regional justice. Withdrawing from the protocols directly ended ongoing cases of Beninese journalists and opposition leaders and a case by former Ivorian presidential candidate Guillemme Soro.17Vidjingninou, F. ´Pourquoi le Bénin se retire du protocole de la Cour africaine des droits de l’homme`. Jeune Afrique, 25 April 2020. Another point of contention was critique at the independence of Benin’s electoral commission. Ibrahim Tounkara, G. ´La réforme de la Commission électorale`. Voice of America, 13 February 2019.

These are also less visible – but in the long run more crucial – consequences of the COVID-19 outbreak. Governments are subtly exploiting the crisis to repress opposition and manipulate elections. Using newly won emergency powers, the pretext of the health response, and the silence of Western partners to seize an opportunity.

Seizing the opportunity

The regime of Guinean president Alpha Condé has been the most blatant in exploiting the COVID-19 outbreak.18Samb, S. ´Guinea holds contentious referendum despite coronavirus outbreak`. Reuters, 23 March 2020; Human Rights Watch. ´Guinea : Respecting Rights Key Amid Covid-19`. 29 April 2020. In March, Condé pushed through parliamentary elections and a constitutional referendum amid widespread protest.19De Bruijne, K. ´Authoritarianism is Guinea´s first Coronavirus Survivor´. ACLED, 5 May 2020. Right after the popular vote, emergency regulations confined people to their houses, empowered the security forces and banned public gatherings. It allowed Condé to announce a controversial 92% win, silence the street and build a new coalition.

In Togo, contested presidential elections in February secured the fourth victory for President Faure Gnassingbé since 2005, the son of former ruler Gnassingbé Eyadema. Since the elections there have been repeated attempts to arrest opposition leader Agbéyomé Kodjo on 11 February, 28 February, and 9 April – each time prevented by the mobilization of Kodjo supporters.

As COVID-19 hit, parliament withdrew Kodjo’s immunity and allowed the Togolese president to rule by decree. On 21 April, with likely fewer supporters around his house due to a coronavirus-curfew, Kodjo was arrested. A 5,000-men strong COVID-19 squad has been maintaining ‘order’ since 4 April and acts as a badly concealed reminder of the power of Gnassingbé-family rule.

In Sierra Leone, the government has used a COVID-19-related prison riot on 29 April as an excuse to make arrests. Initial reports suggested the riot began when an inmate tested positive for COVID-19.

Soon after the incident the ruling Sierra Leone Peoples Party (SLPP) claimed the opposition had attempted to break detained members out of prison and launch a coup. The All People Congress (APC) opposition instead claimed the SLPP manufactured the incident as a pretext to crackdown on the opposition. Various APC officials have been arrested in the weeks since.

Electoral manipulation

Governments are also taking the pandemic as an opportunity to manipulate upcoming elections. Benin just concluded local elections on 17 May, Cote d’Ivoire will hold its presidential elections on 31 October, as will Guinea in the same month, and Burkina Faso, Ghana and Niger will all hold presidential and legislative elections on 22 November, 7 December, and 27 December, respectively.

Regimes will consider whether holding elections or rather postponing them gives them a strategic advantage

Holding elections amidst the COVID-19 crisis will likely result in lower voter turn-out, restrict public manifestations and campaigning, move campaigns online and derail electoral processes such as voter registration.

Regimes will consider whether holding elections or rather postponing them gives them a strategic advantage.20For a debate on elections and COVID-19 see; Anselm Odinkalu, C. ´African elections and COVID-19: A crisis of legitimacy`. The New Humanitarian, 27 April 2020; Assignon, C. ´Quand le coronavirus perturbe les élections en Afrique`. Deutsche Welle, 1 April 2020; Mackay, S. ´Elections in the Time of COVID-19`. Netherlands Institute for Multiparty Democracy, 23 April 2020; Slim, H. ´Can African Elections Move Forward During a Pandemic?´. Corporate Foreign Policy, 16 April 2020; Tyburski, L. ´African elections in the time of coronavirus´. Atlantic Council, 24 March 2020; Ahidjo-Iya, N., Hounkpe, M. ´Elections in the time of COVID-19 – What can West Africans do to prepare?` OSIWA; Oulepo, A. ´ COVID-19 Impact on Africa Elections´. The Cairo Review of Global Affairs, 5 May 2020. For example, the first-ever online meeting of ECOWAS’ heads of state on April 22 saw a proposal to postpone all upcoming elections in West Africa. This benefitted some of the larger West African states but denied other states a clear win. Unsurprisingly, the plan was torpedoed.

Some regimes benefit by holding elections, like those in Guinea, Mali and Benin. In Mali, the government pushed through the March/April legislative elections despite the COVID-19 outbreak and the kidnapping of opposition leader Soumaïla Cissé. President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita believed the elections (postponed since October 2018) were essential to re-legitimize the National Assembly as part of the 2015 Algiers Accords peace process.

As such, despite his party losing a few seats in parliament and a low voter turnout (for example only 12,5% in the capital Bamako), the elections benefited the regime.21Schmauder, A. ´The Upcoming Malian Legislative Elections´. Clingendael Institute, 28 March 2020; Mondafrique. ´Mali, des élections législatives qui ont perdu leur légitimité`. 20 April 2020. Immediately following the results, the government passed a law bypassing the newly elected parliament.22Essor. ´Assemblée nationale : Le gouvernement autorisé à prendre certaines mesures par ordonnances`. Majijet, 24 April 2020.

Local elections also went ahead in Benin.23Jeune Afrique. ‘Élections au Bénin : un scrutin calme, mais des craintes de forte abstention’. 18 May 2020. Public demonstrations have been banned due to COVID-19, denying the opposition an opportunity to mobilize supporters and show strength.24Africa Radio ´Bénin : vers de Nouvelles Èlections sans Èlecteurs ?´. 7 May 2020. There are credible claims of regime public campaigning outside of the major town. Campaigns were moved online and into the hands of the media, a domain firmly controlled by the regime after years of repression.25Ouitona, S. ´Élections locales au Bénin : une campagne pas comme les autres`. Le Nouvel Afrik, 1 May 2020.

In rural Benin, votes are not delivered through brokers like chiefs but by local state officials,26Koter, D. Beyond Ethnic Politics in Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016. Bierschenk, T. ‘The Local Appropriation of Democracy: An Analysis of the Municipal Elections in Parakou, Republic of Benin, 2002–03’. The Journal of Modern African Studies 44, no. 4 (December 2006): 543–71. whose support the regime had already secured prior to the COVID-19 outbreak. Coupled with likely low turn-out, it is clear why President Patrice Talon has consistently downplayed the effects of COVID-19 and pushed for elections.27The opposition is silent due to a deal allowing them to stand (unlike 2019 were the full opposition was banned).

As expected, other regimes will benefit by postponing popular votes, as in Côte d’Ivoire, Burkina Faso, and Senegal. In Côte d’Ivoire, President Alhassan Ouattara allegedly told the cabinet he considered postponing the elections.28Mieu, B. ´Coronavirus and Africa – Towards a Postponement of the Presidential Election in Ivory Coast?`. Institute Montaigne, 21 April 2020. Navarro, N. ´À la Une: le décalage de la présidentielle en Côte d’Ivoire à cause du coronavirus`. RFI, 17 April 2020. Africa Intelligence. ´La pandémie pourrait entraîner le décalage de la présidentielle ivoirienne`. 15 April 2020; Mieu, B. ´Coronavirus and Africa – Towards a Postponement of the Presidential Election in Ivory Coast?`. Institute Montaigne, 21 April 2020. One reason is that the plan to manipulate voter registration through high fees and few registration centers was thwarted by outside funding and pressure.29Mainly European Union.

The Nigerien elections of December 2020, likewise, may be postponed. It is the last year in office for President Mahamadou Issoufou, but the regime’s authoritarian proclivities persist.30Cascais, A. Niger’s chance for a democratic transition of power. DW. February 2020. Voter registration has been suspended in Niamey because of COVID-19 and will by all accounts not be completed by the June 17 deadline.31The opposition has already accused Issoufou of not respecting his constitutional duties. Nigerdiaspora. Pandemie du coronavirus et processus electoral au Niger. April 2020. http://nigerdiaspora.net/index.php/politique-niger/9061-pandemie-du-coronavirus-et-processus-electoral-au-niger-la-constitution-va-t-elle-etre-mise-entre-parentheses With a track record of authoritarian tendencies and a succession to handle, Issoufou may use COVID-19 to delay elections.32The government has deliberately used the fragile security policy situation to act against its critics. Human rights leaders have been thrown in jail on charges of working for Boko Haram.

Regional instability and response

Suppressing the opposition is the wrong move at the wrong time, as West Africa’s coastal states are in danger. Extremist Groups from the Sahel seek to expand into the Gulf of Guinea. They have mastered the subtle art of exploiting political exclusion and local discontent to cement their positions.

Opposition alliances with violent extremist organizations will be far more consequential to regime stability than any short-term political gain achieved by exploiting the COVID-19 crisis

The more the opposition is pushed to the fringes, the more the temptation beckons of a marriage of convenience with violent extremist organizations.33As we have seen in Burkina Faso with some of the old Compaore regime and in North-East Nigeria. Such alliances will be far more consequential to regime stability than any short-term political gain achieved by exploiting the COVID-19 crisis.

Instability in the Gulf of Guinea threatens European economic, security and geopolitical interests. West Africa remains the EUs’ largest trading partner in Sub-Saharan Africa. Instability has not only economic consequences – for example, the Netherlands is the largest importer of cacao in the world – but will also amplify the appeal of Jihadi groups, strengthen organized crime groups (e.g. cocaine traffickers), increase migratory pressures and allow countries like China, Russia and Turkey to further expand into the region.

To counter these developments, West African governments need to adopt inclusive policies. Mohamed Ibn Chambas, the UN special representative for West Africa, argues: “it is crucial for us to seek consensual and genuinely inclusive ways of addressing any disruptions to electoral schedules.”34Note during the online ECOWAS meeting. UNOWAS. ´Statement by H.E. Dr. Mohamed Ibn Chambas`. 23 April 2020.

Specialists contend that preventing violent extremism in the region has to start and end by offering genuine political space to the opposition. Regime survival is best ensured if prominent opposition members have alternative courses of action, limited as they may be.

ECOWAS could reclaim its role in countering authoritarianism – as it did in Guinea-Bissau (1999-present), Ghana (2008), Guinea (2010), Benin (2011), and Liberia (2011), among others.35Conflict Research Unit. ‘Regional responses to conflict and instability´, DANIDA briefing (internal), 2018; Africa Center for Strategic Studies. ´ECOWAS Risks Its Hard-Won Reputation`. 6 March 2020. But existing links between rulers and opposition from neighboring counties – as in Sierra Leone, Liberia, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Niger, and Mali – and extremist spill-over make this increasingly difficult.

Thus, more than ever, the European Union and individual member states have to flex their muscles to pressure and entice West African regimes to take up inclusive governance. Western European states should pursue an active foreign policy in times of COVID-19, not just for normative reasons but also out of sheer self-interest.