The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the socio-economic and political landscape in Central America – again revealing the degree to which criminal actors are intertwined with local, national, regional, and even global economies. New restrictions on mobility and business activity have forced gangs and cartels to adapt, with major consequences for security and stability. ACLED data show an increase in inter-gang violence across the region. In Mexico and the Northern Triangle, gangs are competing over a shrinking criminal market, and governments are faced with rising violence as they struggle to address an unprecedented health crisis. As the pandemic wears on, gang violence seems likely to rise.

Pandemic-related restrictions and gang activity

Governments in Central America have imposed a variety of measures to contain COVID-19. The government of Mexico officially declared a national health emergency on 30 March 2020 after its first case of COVID-19 was reported at the end of February, suspending non-essential economic activities and advising the population to shelter at home. Some Mexican states imposed further restrictions in addition to the federal order. In the Northern Triangle countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, governments began establishing preventive measures in mid-March, albeit with different degrees of stringency. On 13 March, Guatemala introduced a travel ban for any person arriving from Canada and the United States. Meanwhile, in El Salvador and Honduras, a state of emergency was announced on the 13 and 16 March, respectively. These measures were followed by a national quarantine at the end of March in El Salvador, and curfews during the first week of April in Guatemala and Honduras.

These restrictions have had immediate impacts on gang operations. Locally, the temporary closure of non-essential economic activity has hindered money laundering, as it is traditionally carried out through front businesses that appear to be engaged in legal commerce, while mobility restrictions have similarly impeded extortion rackets. Globally, the demand for recreational drug use has decreased amid the pandemic, and travel restrictions obstruct both drug users looking to purchase as well as drug traffickers aiming to supply (Global Initiative, May, 2020).The reduction of the international traffic of goods and passengers also makes the discovery of illegal cargo by authorities more likely, resulting in the scarcity of certain chemical products essential for drug production (InSight Crime, 18 March 2020).These challenges have forced cartels to seek alternative means of drug distribution and income generation during the crisis.

Gang adaptation and its effects on violence trends

Mexico

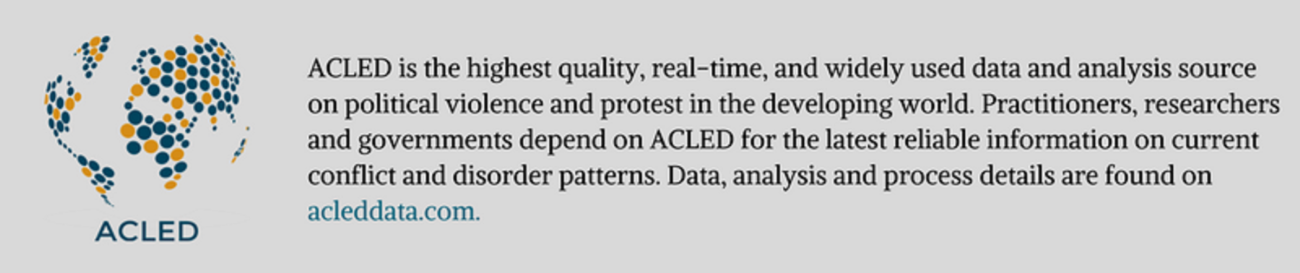

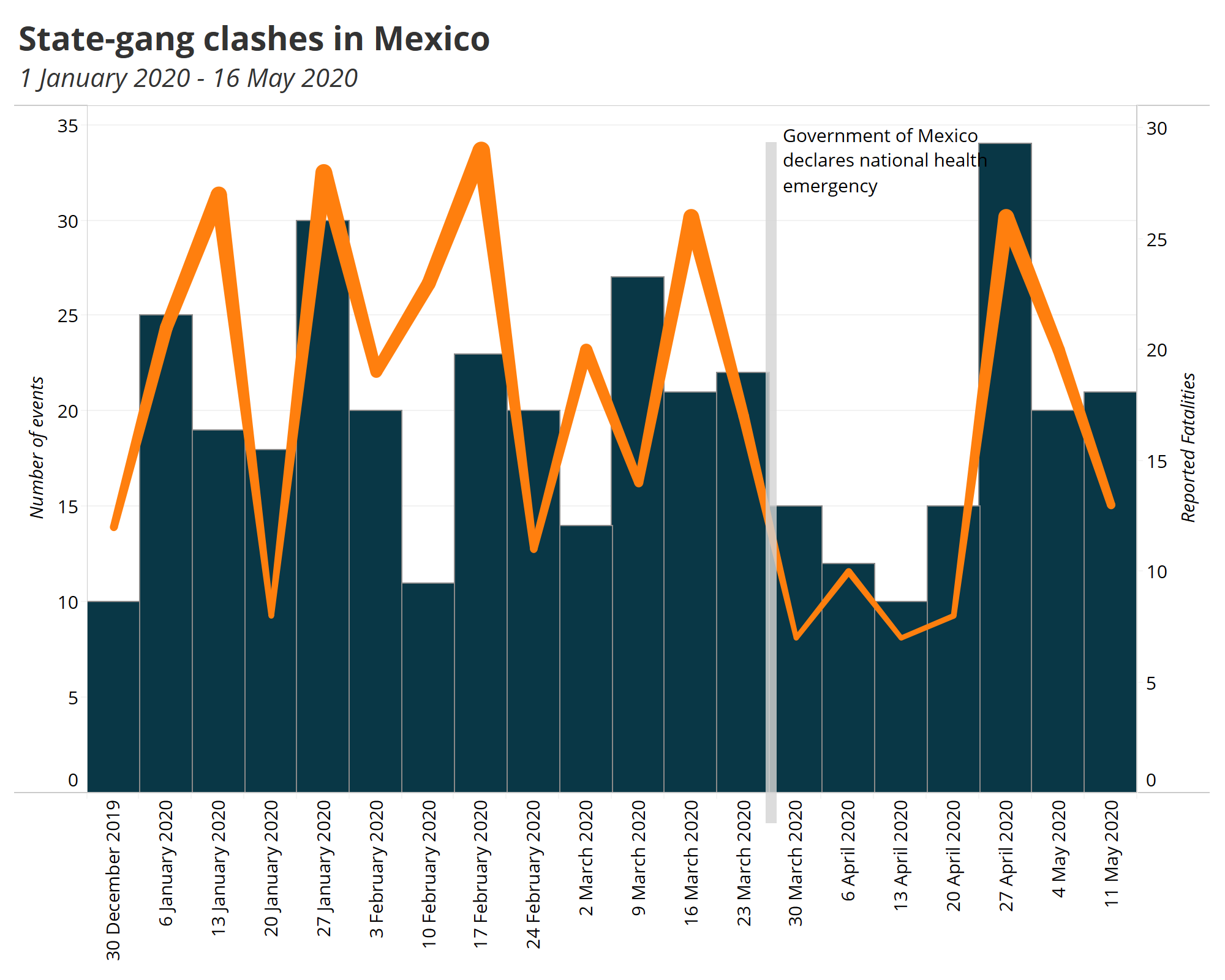

Criminal violence has risen in Mexico in recent years (El Universal, 21 January 2020). This escalation can be partially attributed to the fragmentation of cartels, which has led to violent competition among splinter groups over existing drug trade infrastructure, even as they constantly evolve and diversify their criminal activities. The pandemic has intensified these trends. COVID-19’s disruption of markets and trafficking routes has aggravated the struggle for control over territory that remains viable for criminal activity. ACLED data show that after a short decrease in gang violence around when the state of emergency was declared, cartels ramped up activity in April as they vied over access to limited resources (see navy bars in graph below). Battles between cartels are becoming more lethal, with a substantial increase in the number of reported fatalities stemming from inter-gang clashes (see orange line in graph below). Certain gangs have particularly increased their activity during the pandemic: the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG), Los Viagras, and Union Tepito. CJNG activity expanded into two new states – Veracruz and Puebla – which had previously been free of CJNG violence in 2020 up to that point (for more information, see this spotlight piece on cartel activity across Mexico from ACLED’s COVID-19 Disorder Tracker).

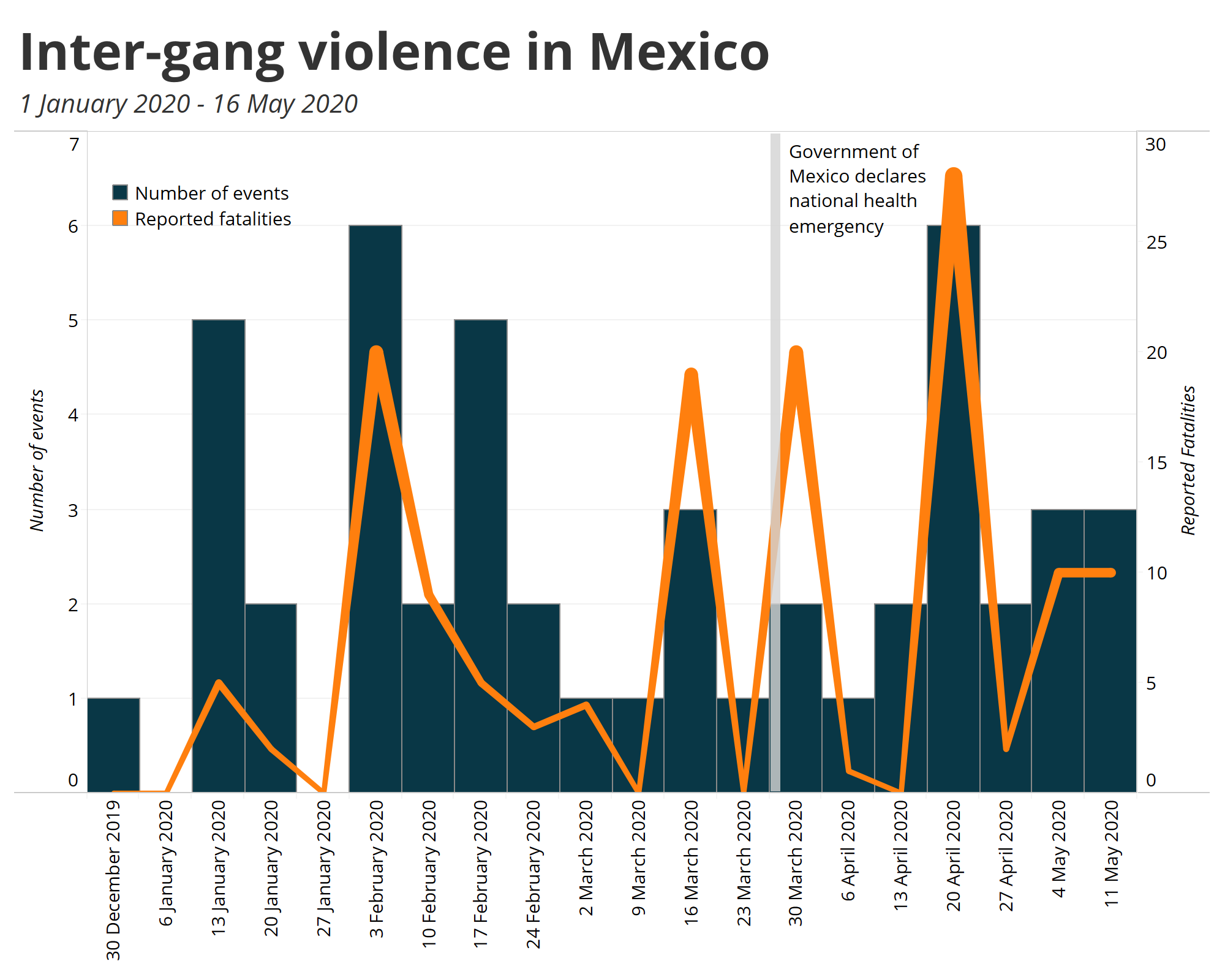

The health emergency and the consequent economic crisis will certainly shift the balance between cartels and lead some to seek new business models (Al Jazeera, 29 April 2020). Smaller gangs, or those with less economic capacity, are threatened by more established groups and may try to survive by diversifying into violent street crime, extortion, kidnappings, and attacks (Infobae, 25 April 2020). Despite COVID-19 quarantines and stay-at-home orders, Mexico’s homicide rate hit a new high in March 2020 (Government of Mexico, 21 March 2020). In multiple states, violence targeting civilians has increased during the pandemic compared to months prior, including in Jalisco, Sonora, and Nuevo Leon (see map below). The escalation suggests that some groups are using the crisis to expand and reinforce their presence. For example, in Nuevo Leon, attacks on civilians hit unprecedented levels in April compared to the last 12 months, with multiple drive-by shootings. Several new criminal groups have emerged recently and this state alone is disputed by at least six groups seeking to seize the territory to transport drugs to the United States (Milenio, 12 June 2020, ABC Noticias, 10 January 2020).

Northern Triangle: El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala

In contrast, violence targeting civilians has decreased significantly in all three countries of the Northern Triangle since the official start of the pandemic in March. Extortion is a key source of income for gangs – also known as maras, locally. Many businesses have closed or lost revenue during the pandemic, hence preventing them from paying gang rents. As a result, extortion income has dropped (GI-TOC, 15 April 2020).

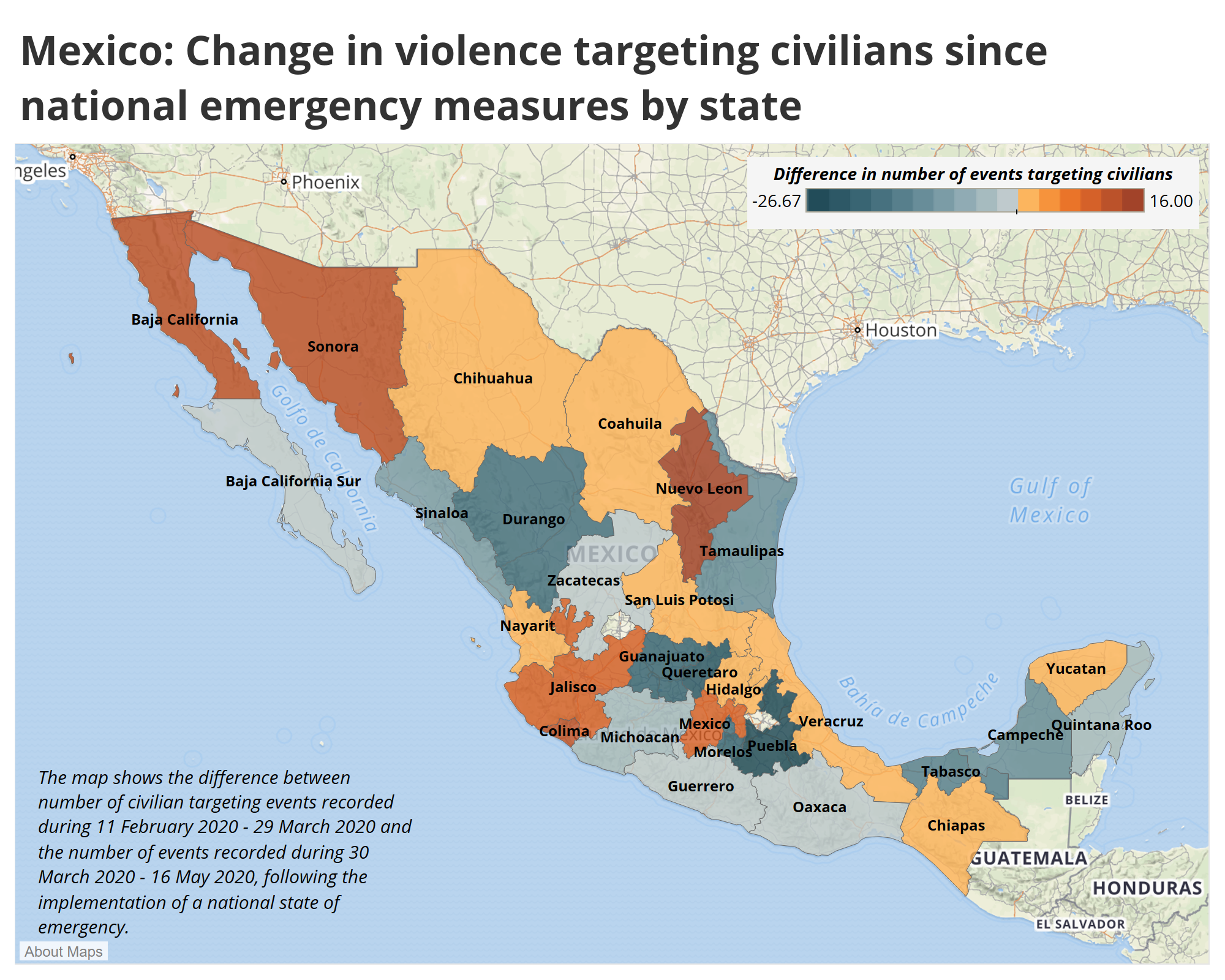

Economic pressures have led to increased competition in Honduras, where battles involving gangs as well as reported fatalities stemming from gang violence have spiked, hitting their highest levels of the year (see graph below). Inter-gang fighting has particularly increased across the country, with multiple clashes between the larger mara groups Mara Salvatrucha 13 (MS-13) and Barrio 18 (B-18) and smaller local gangs.

Gangs vs. state forces – new dynamics in old conflicts

Mexico

In Mexico, social and political tensions exacerbated by the pandemic have led to a reorientation of the security forces. In mid-April, members of the National Guard, a force created by President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador in 2019 to fight gang violence, were deployed to protect hospitals and warehouses storing healthcare equipment from attacks and looting, while state and municipal police were tasked with enforcing social distancing rules (Agencia EFE, 21 April 2020). The preoccupation of the security forces with the public health emergency resulted in an initial reduction in the number of clashes between cartels and state forces at the beginning of the pandemic (see graph below). Cartels soon seized the moment to intensify turf wars and to expand into new territories, however, leading to a spike in attacks on state forces at the end of April (see graph below).

El Salvador

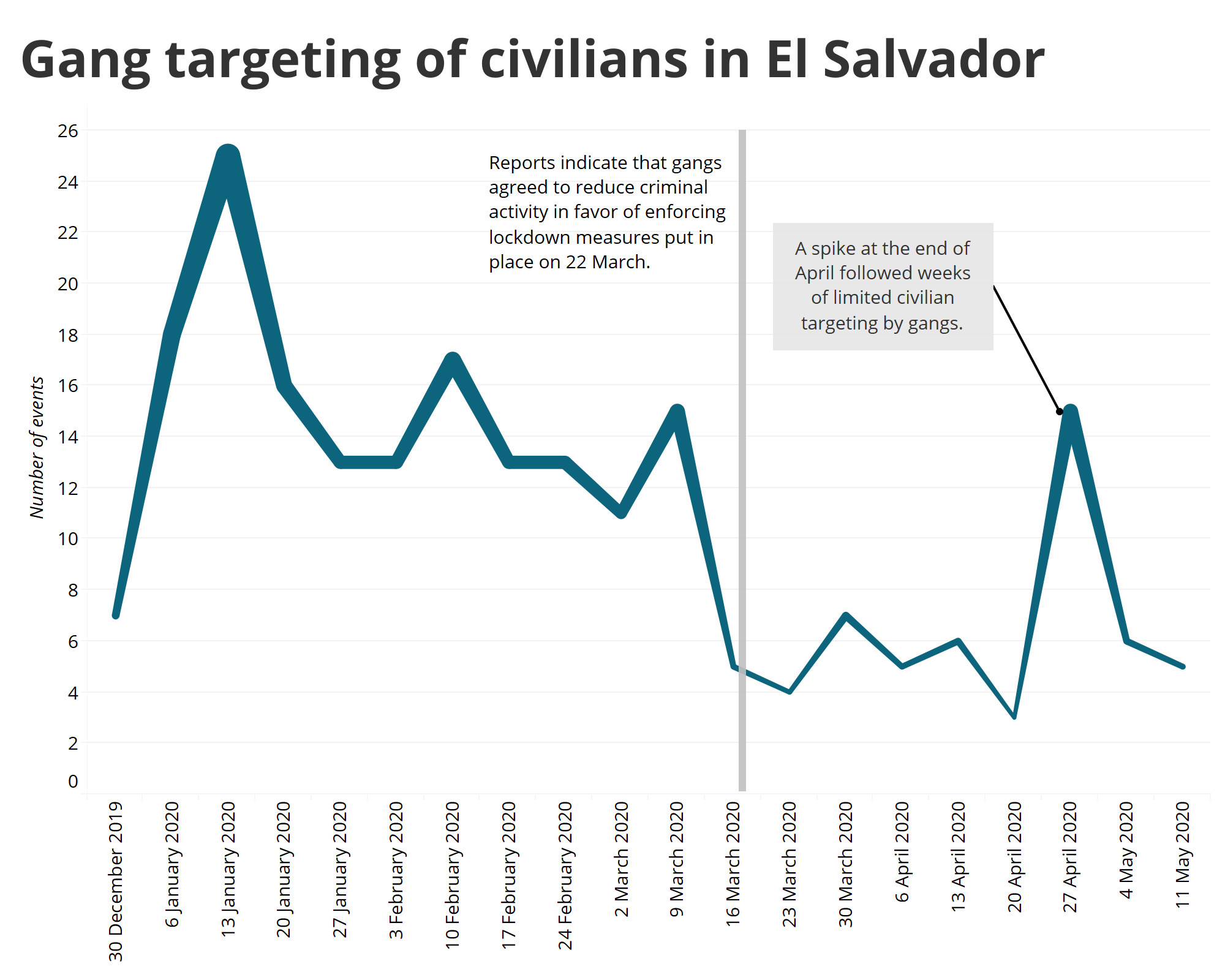

The two largest gangs in El Salvador, MS-13 and the two factions of the B-18, initially promised each other that they would restrict criminal activities in light of the coronavirus (El Faro, 30 April 2020). Nevertheless, gang attacks on civilians spiked at the end of April (see graph below) – an escalation seen by some as a reminder to state forces and society at large that they retain control over key territories (El Faro, 30 April 2020).

The outbreak of violence prompted President Nayib Bukele to authorize lethal force against gangs and to order a prison restructuring. Arguing that April’s deadly spike in violence was orchestrated by imprisoned gang leaders, the Bukele administration decided to impose extreme isolation measures on prominent gang-affiliated prisoners. At the same time, the administration also began mixing lower-level members of rival gangs — contravening a long-standing practice of separating gangs within detention centers — on the basis that the new arrangement would sow discord and make it more difficult for gangs to send orders out (BBC, 28 April 2020).

The role of gangs in local communities – holding power by all means

Mexico

The pandemic has created new opportunities for cartels to enlarge their role in local communities. In several Mexican states, cartels have taken steps to address the health crisis by imposing curfews, simultaneously challenging the government’s authority and demonstrating their power in areas under their control. The economic fallout from the pandemic is also magnifying existing inequalities in Central America, which gangs are eager to exploit. This is not a new phenomenon: organized crime groups have long mixed largesse with terror and violence to establish themselves among marginalized communities, delivering goods and services to demonstrate territorial control, form a social base, and develop their brand (CIDE, 27 April 2020). The current health emergency offers additional avenues for cartels to exercise authority and to generate legitimacy: several cartels – among them the Sinaloa Cartel, CJNG, Los Viagras, Familia Michoacana Cartel, and the Cartel del Noreste – have distributed food in an effort to expand their support base among local populations (InSight Crime, 28 April 2020). These activities appear to be particularly concentrated in states that are disputed by different cartels, including Guerrero, Guanajuato, Michoacán, and Tamaulipas. These efforts to build local support through acts of goodwill during the pandemic are likely to further entrench cartel control over critical territory and to deepen the co-dependence of marginalized populations on local gangs (GI-TOC, May 2020). Similar strategies have been seen elsewhere around the globe, from criminal groups in Brazil’s favelas to the Taliban in Afghanistan.

Northern Triangle: El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala

Gangs have also adopted new strategies to demonstrate their power in the Northern Triangle. In El Salvador, maras sent out messages threatening people to comply with the national curfew. They established schedules for stores to open and for residents to obtain food. Reports indicate that the three largest maras – MS-13 and both factions of B-18 – coordinated to implement these measures across the country (El Faro, 31 March 2020), and that gang members have beaten people for not complying (ElSalvador.com, 1 April 2020). In Guatemala, some gangs have suspended the collection of extortion money as a relief measure for struggling markets (El Periodico, 26 March 2020). Although extortion decreased by almost 80% in Honduras in March 2020 when compared to 2019, reports suggest that gangs have threatened transport businesses, warning that extortion payments will be collected retroactively after COVID-19 restrictions are lifted (GI-TOC, 15 April 2020).

Conclusion

Mere months into the pandemic, it is clear that COVID-19 restrictions are affecting gang activity manifold across Central America. New restrictions have led to increased competition for local markets and have forced gangs to adapt their business models, already resulting in changing patterns of violence. With most governments hardening borders, the illegal drug market may face long-term disruptions, pushing organized crime groups to find alternative channels for supply and distribution. These groups have historically proven versatile and quick to adapt to such disruptions, and they have made it clear that they are not willing to give up any territory, income, or local authority in the face of a pandemic.

As the pandemic drags on, and its negative economic consequences intensify, gang violence will likely continue to rise in Central America. With law enforcement overstretched and inter-gang competition on the rise, turf wars will escalate and everyday abuses will go unchecked. The region’s civilians will be left to cope with both the global COVID-19 pandemic and a local epidemic of violence.