Evaluating an IS Resurgence

The historical moment in which the Islamic State (IS) exploded into global infamy was unique. In 2011, three years before the emergence of the caliphate, the Arab Spring had begun to destabilize political orders across the Middle East. In Syria, the uprising quickly morphed into a full-fledged civil war. Fighters from Al Qaeda’s branch in Iraq — AQI, or the group which would become IS — crossed the border into Syria to join the fight. They found the conflict’s complexity ideal for growing and strengthening the group, which organized with ease across the porous border with Iraq (Brookings, 24 February 2015). As the group’s ambitions grew more radical and its tactics more brutal, Al Qaeda’s central leadership lost control, disassociating from their most powerful branch in early 2014. Less than six months later, IS leader Abu Bakr Al Baghdadi stood at the minbar of Mosul’s Grand Mosque and announced his rulership over a physical caliphate stretching across Syria and Iraq, from Aleppo to Diyala (Wilson Center, 28 October 2019).

IS’s rise from dormancy in 2011 to seizing Iraq’s second-largest city in 2014 took place gradually, then all at once (Encyclopedia Britannica, 17 September 2014). It occurred not only against the backdrop of the Syrian Civil War, but also amidst political turmoil in Iraq. Then-US President Barack Obama had withdrawn troops from Iraq in 2011 (Washington Post, 21 October 2011) and the country’s security forces collapsed completely in 2014. During this time, IS’s Iraqi recruitment pool of Sunni Muslims was increasingly disenfranchised, and were frequently targets of state and communal violence. Iraqis in general distrusted and were underserved by the dysfunctional and divided national government established over the course of the US invasion and occupation.

IS capitalized on the opportunities provided by these extraordinary historical conditions to pave the way for its shocking ascendancy. Can the IS of 2020 pull off a similar feat in the Iraq and Syria of 2020, the territory spanned by its once-caliphate? The constraining factor is not the group’s will to fight, but its ability to exploit operational context to its advantage. Six years since the group declared its caliphate, this context has shifted significantly. A new IS resurgence will not mirror IS’s rise in the past, but will take advantage of new circumstances, such as the late 2019 Turkish invasion of northern Syria. The group itself is different: the IS of 2020 is more infamous, independent, and global than the IS of 2014 — and Syria and Iraq are different as well. IS appears prepared to exploit any opportunity to expand its capabilities and to alter its strategy to best meet the historical moment. New developments, such as increased US-Iran tensions and the COVID-19 pandemic, are beginning to provide such opportunities.

Then & Now: Conditions Shaping the Future of IS

The Iraqi government declared IS’s defeat in Iraq near the end of 2017, and the Syrian Democratic Forces (QSD) cleared the group from its last territorial holdouts in Deir-ez-Zor in March 2019 (Wilson Center, 2019). Several developments since then have impacted the group’s ability to re-emerge from the so-called ‘defeat’ of its caliphate, including the changing nature of Syria’s civil war, escalating tensions between the US and Iran, mass unrest in Iraq, the coronavirus pandemic, a Sunni population suspicious of IS intentions, and the destruction of IS’s highest leadership circles.

Syrian Civil War & Turkish Intervention

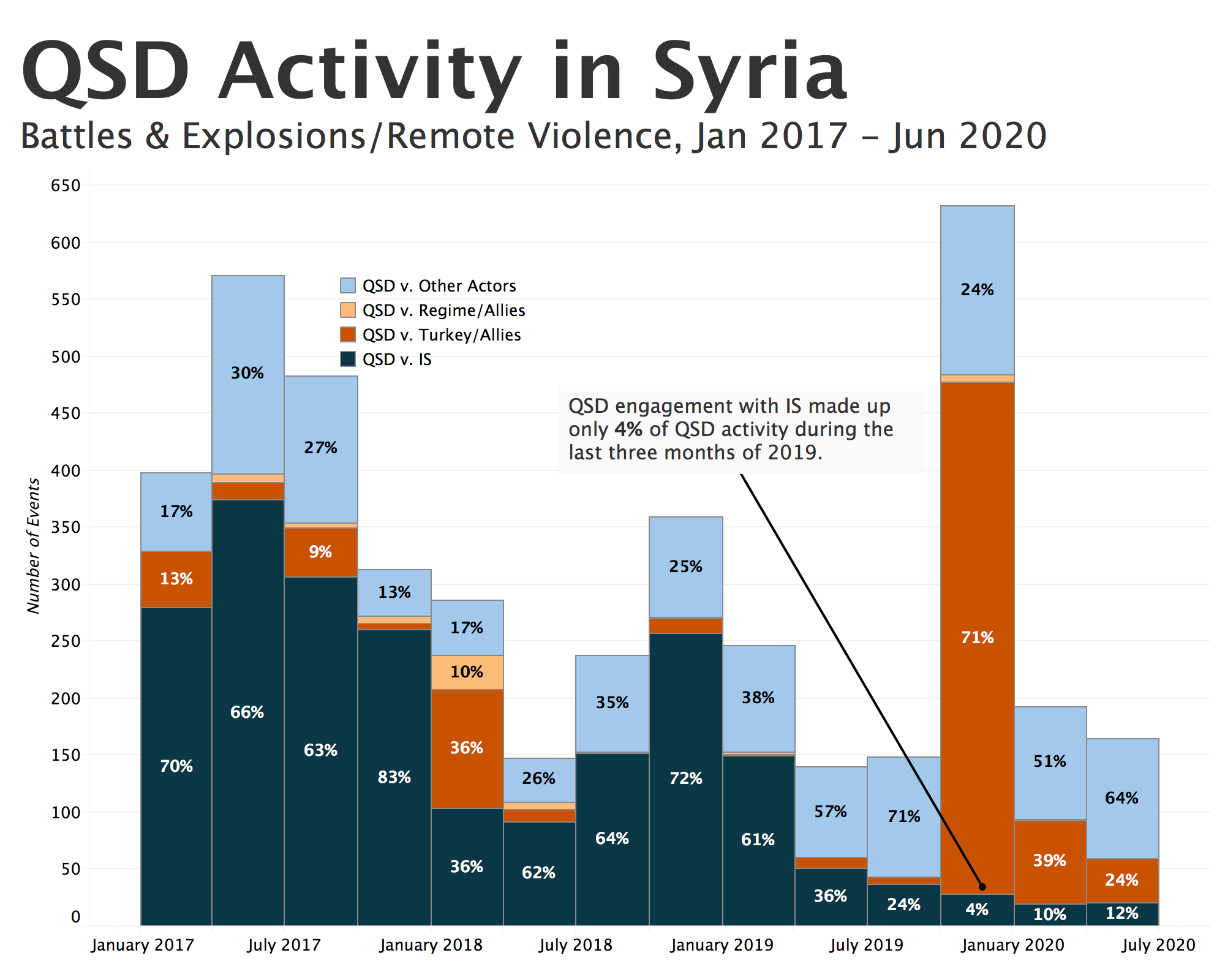

Syria’s civil war was at its height during IS’s rise, creating a permissive environment for the group, as well as steady pools of fighters and weapons (International Crisis Group, 11 October 2019). Syria remains unstable, but the regime and its allies have consolidated control over large amounts of territory lost during the war’s early years, reducing IS’s ability to move as freely as it did from 2011 to 2014. However, Turkey’s late-2019 intervention in Northeastern Syria threatens to upset this balance and enables IS to regroup. The QSD has been forced to divert attention away from IS to combat Turkey (see Figure 1). This shift may allow IS freedom of movement and provide relief from clearing operations.. In the final quarter of 2019, the Turkish invasion into Kurdish territory in Syria caused QSD-Turkey engagements to skyrocket, and brought QSD activity against IS to its lowest level since at least 2017 (for more, see ACLED’s most recent State of Syria map covering the first quarter of 2020.) The QSD in fact issued a declaration stating that it would suspend any anti-IS operations in the event of a Turkish advance, especially in light of the US withdrawal from the region (Reuters, 9 October 2019). Since then, the number of engagements between IS and the QSD has only fallen further.

Figure 1.

The escalation of tensions between Iran and the US

The escalation of tensions between the US and Iran has also produced security gaps that IS has since exploited. Tensions threatened to boil over in Iraq after the US assassination of Iranian General Qassem Soleimani in Baghdad in January 2020 (Inherent Resolve, 8 May 2020). The attack on Soleimani also killed Iraqi Abu Mahdi Al Muhandis, deputy commander of Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) – a divisive figure who was nevertheless a powerful influence in the PMF, one of Iraq’s most effective anti-IS forces (The Century Foundation, 13 February 2020).

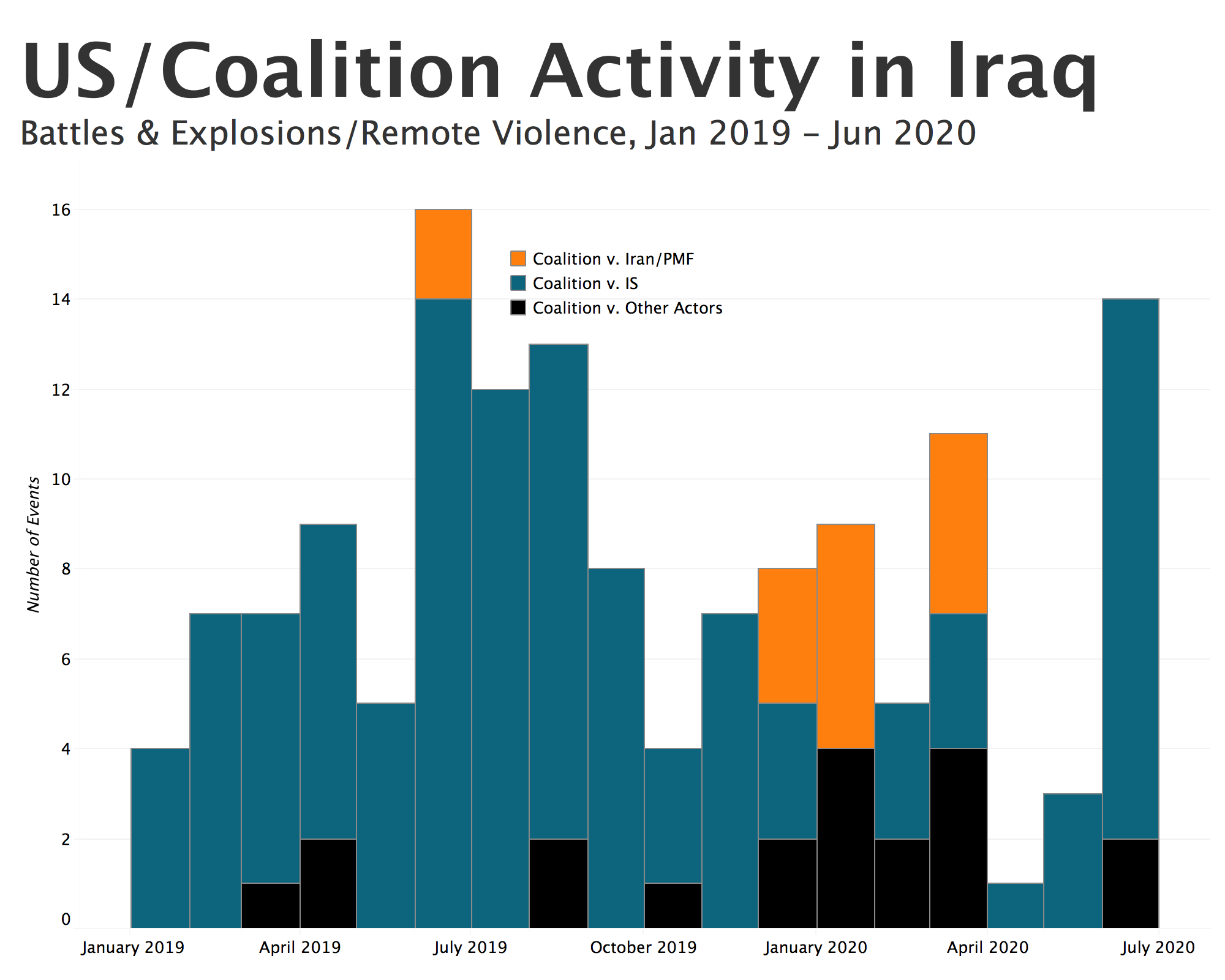

The assassinations have already impacted the anti-IS fight in Iraq. Reports suggest that anti-IS raids by US troops decreased as tensions between the US and Iran escalated, and as the US diverted resources towards protecting its troops from Iran-backed attacks (see Figure 2). Following IS’s spring campaign, coalition forces again intensified attacks against IS hideouts in June (Shafaaq News, 4 June 2020). This is the general pattern of coalition activity: immediately following surges of IS activity, when the group is rebuilding and is at its most vulnerable, the coalition intensifies efforts to target IS leaders and infrastructure. However, while other coalition member states may retain this freedom of engagement, US troops — the leading force of the coalition — have been limited by Iranian militia activity and distracted by threats to personnel. PMF units have reportedly prevented US troops from accessing areas of IS activity (Foreign Policy, 29 May 2020). Moreover, the Soleimani assassination prompted the Iraqi parliament to call for the withdrawal of all US troops from Iraq, amidst widespread fears that the country is at risk of becoming a battleground for influence waged by Iran and the US (for more on this, see the recent ACLED piece entitled Iraq’s October Revolution: Six Months Later). While not legally binding, the resolution nevertheless indicates the unsustainability of current anti-IS arrangements, and potentially foreshadows impending US withdrawal of the few troops that remain (Atlantic Council, 5 January 2020; Military Times, 8 July 2020).

Figure 2.

The coronavirus pandemic

The threat of US withdrawal has been accompanied by the withdrawal of other coalition members, largely as a result of the coronavirus pandemic (Il Fatto Quotidiano, 26 March 2020). A full coalition withdrawal would leave an inarguably wounded counter-IS force, allowing IS to potentially build up strength in hard-to-reach terrain. The Iraqi government’s capacity to dedicate itself to anti-IS efforts is also dwindling due to the coronavirus’s drain on state resources. IS has released editorials encouraging its followers worldwide to take advantage of the crisis and to continue waging global war, while tensions provoked by the pandemic may provide just the unrest that IS seeks to exploit (International Crisis Group, 31 March 2020).

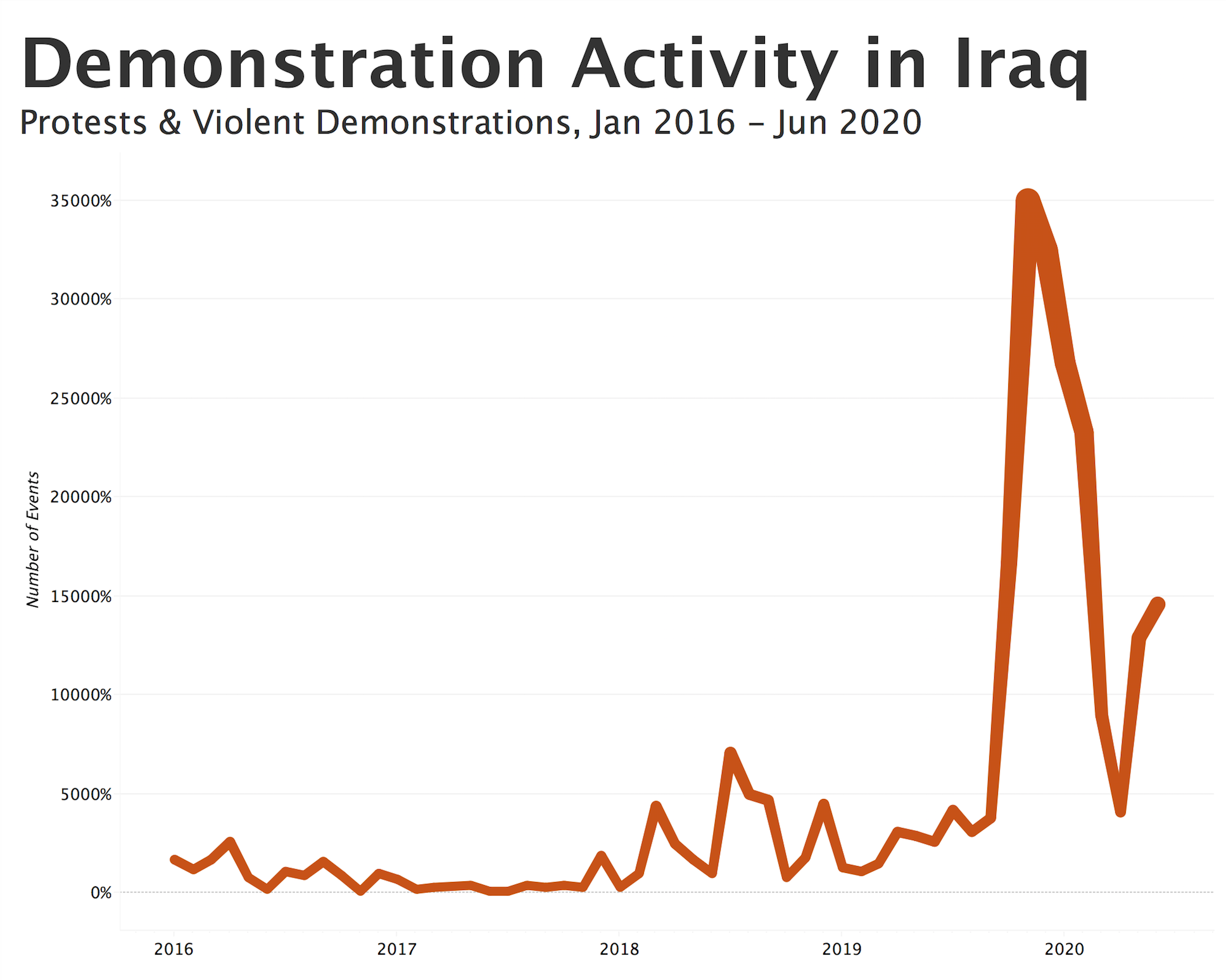

Widespread discontent in Iraq

Economic fallout from both Iran-US tensions and the pandemic have fueled widespread popular discontent in Iraq (ACLED, 10 April 2020D). The country’s economic situation is dire, with record-low oil prices and renewed US sanctions on Iran taking a heavy toll on the population, which relies on Iranian gas imports. These pressures may require Iraq’s new and untested government to implement austerity measures in the midst of a pandemic and at a high point of public unrest. Years of war, inept governing, and economic collapse pushed Iraqis to the streets in late 2019 in a massive wave of demonstrations that led to the resignation of the prime minister. While these demonstrations have slowed during the pandemic (see Figure 3), the movement’s core concerns have not been alleviated, and protests are again on the rise (International Crisis Group, 8 May 2020). The country’s new prime minister, Mustafa Al Khadhimi, was only appointed in May; whether he will be more successful than the previous administration in bridging Iraqi society’s divides remains to be seen.

Figure 3.

Sunni suspicion of IS

Yet, while IS took advantage of popular discontent and deep sectarian divides in Iraq during its 2011-2014 rise, the group may not be in a position to do so again (see ACLED’s Mid-Year Update: Ten Conflicts to Worry About in 2019 for more on issues facing Iraq after IS’s ‘defeat’). While sectarianism is still very much a major dynamic in Iraqi society, Sunnis in 2020 Iraq are unlikely to see IS as a viable solution – IS’s potential pool of support has dwindled. After all, IS’s devastating tactics and ruthless governing impacted Sunni Muslims more than almost any other group. This may pose a particular problem for IS: many of IS’s clandestine networks were exposed as it became more powerful, leaving far fewer in place in 2020 than in 2014. The group likely needs increased membership in order to effectively re-emerge (International Crisis Group, 11 October 2019). As it stands, far from attracting widespread popular support, those who had collaborated with IS are often disenfranchised in modern Iraq, risking the country’s long-term cohesion (Center for Global Policy, 7 July 2020). Previous IS efforts to resurge after setbacks have largely taken place amidst a backdrop of intense sectarian rivalry, purposefully stoked by IS fighters. It is unlikely that this tactic, given what Sunnis know now of IS, will win over the networks vital to a rapid resurgence.

Coalition targeting of IS leadership

Finally, IS faces pressure from coalition targeting of its leadership – though it remains to be seen if this will significantly influence its capacity to regroup. ‘High-value targeting’ of the upper echelons of IS’s organizational structure is a longstanding coalition tactic, and one the group has adapted to accommodate. In late 2019, the US killed IS’s leader and caliph, Baghdadi, who had led since before the group’s split from Al Qaeda (BBC, 28 October 2019). The coalition and its allies have continued to target IS leadership in the months since (Inherent Resolve, 22 May 2020). However, IS’s cadre structure allows the group flexibility, and the leader who replaced Baghdadi – Mohamed Al Mawla – has thus far had a less visible role in the organization (Center for Global Policy, 19 May 2020).

What will IS’s resurgence look like – and what is it doing now?

Given these conditions, what would an IS resurgence look like? Are there any indicators that the group is seizing on the opportunities afforded by these conditions to strengthen its position?

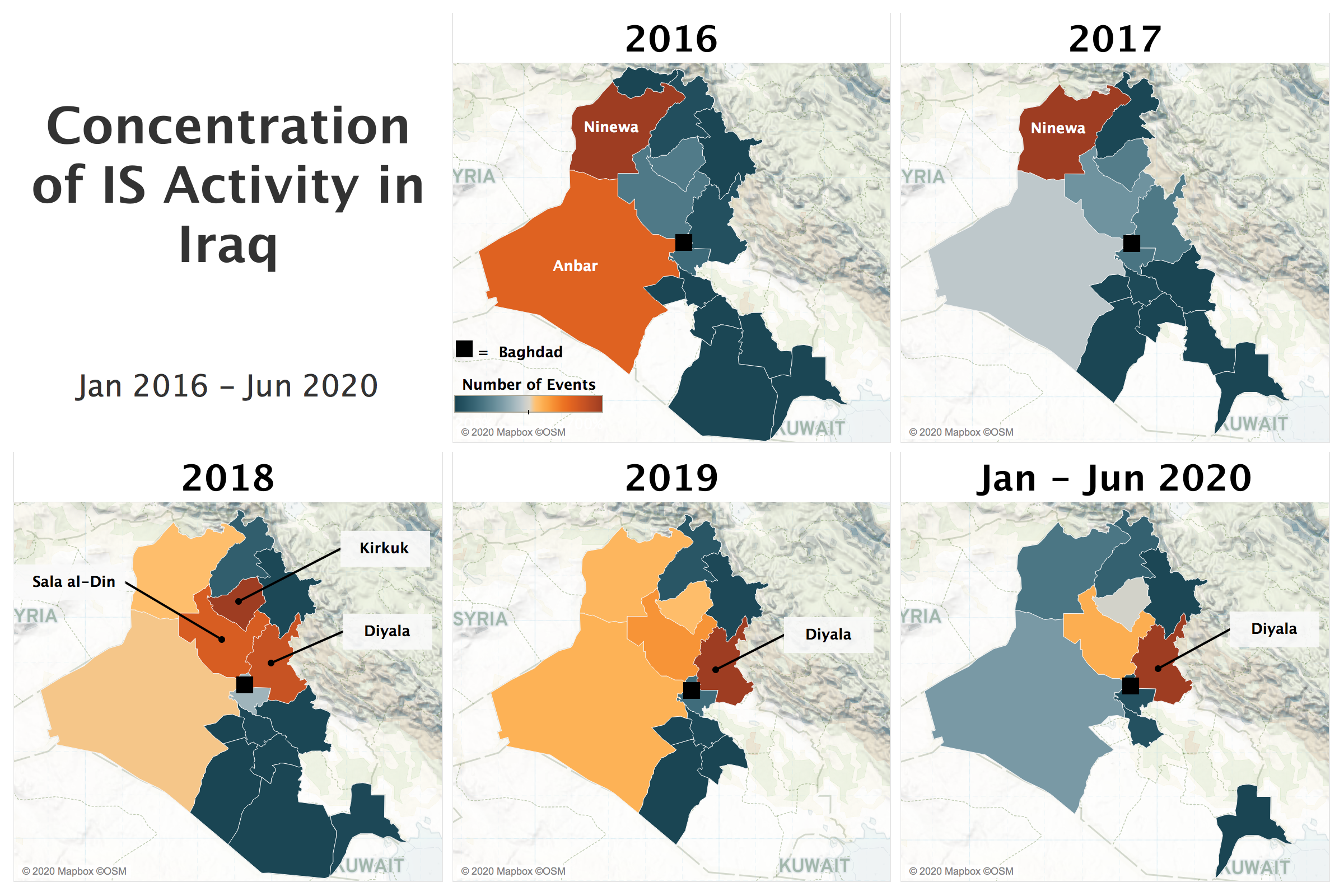

IS’s presence now is primarily concentrated in northeast Iraq, in the disputed provinces of Diyala, Kirkuk, Sala al-Din, and Ninewa, suggesting that the group is making a strategic attempt to rebuild its strength. These areas have previously been used as sites for IS to regroup and reaffirm its presence in Iraq, and feature both intense sectarian divides and patchwork security forces alienated from the population. Hotspots of IS activity have shifted slightly southwards in Iraq over the past several years: IS has moved primarily from Kirkuk to increasing its activity in Diyala and Sala al-Din (see Figure 4), where human and physical geography makes clearing operations difficult, and which bring IS activity closer to big cities (Washington Institute, October 2016). This movement south towards Baghdad is also a hallmark of IS’s earlier strategy, which had the stated intention of forcing Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) to ‘cede the countryside’ and retreat into cities. Additionally, large attacks carried out in major metropolises not only showcase the group’s strength, but also divert the ISF to concentrate their efforts within city limits, outside IS’s support zones, thus leaving the group free to strengthen and rebuild in the countryside. So far this year, IS has conducted at least half a dozen complex, coordinated attacks just skirting Baghdad (see Figure 4) (Twitter, 2 May 2020).

Figure 4.

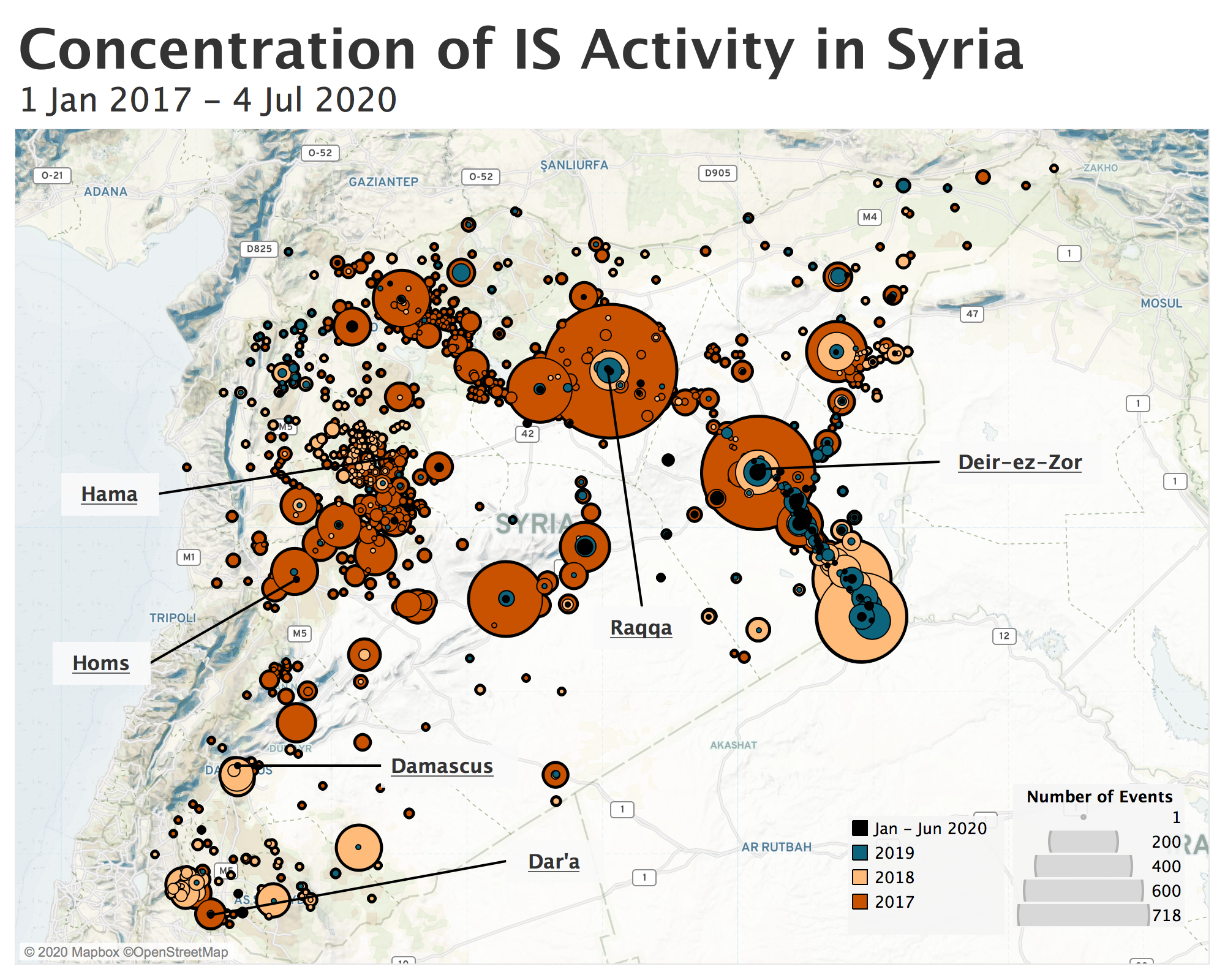

In Syria, the group’s geographic focus is driven by similar motivations. Given the weakness of the QSD and its movement north to combat Turkey, IS has focused on rebuilding its strength in areas of disputed and weak control – drawing QSD focus away from these areas. IS attacks in Syria were previously limited largely to central Syria in the desert between Homs and Deir-ez-Zor, and areas controlled by Kurdish forces. IS has shown that it has the capacity to expand, and in the past months has been active in Hama, Raqqa, and Dar’a (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

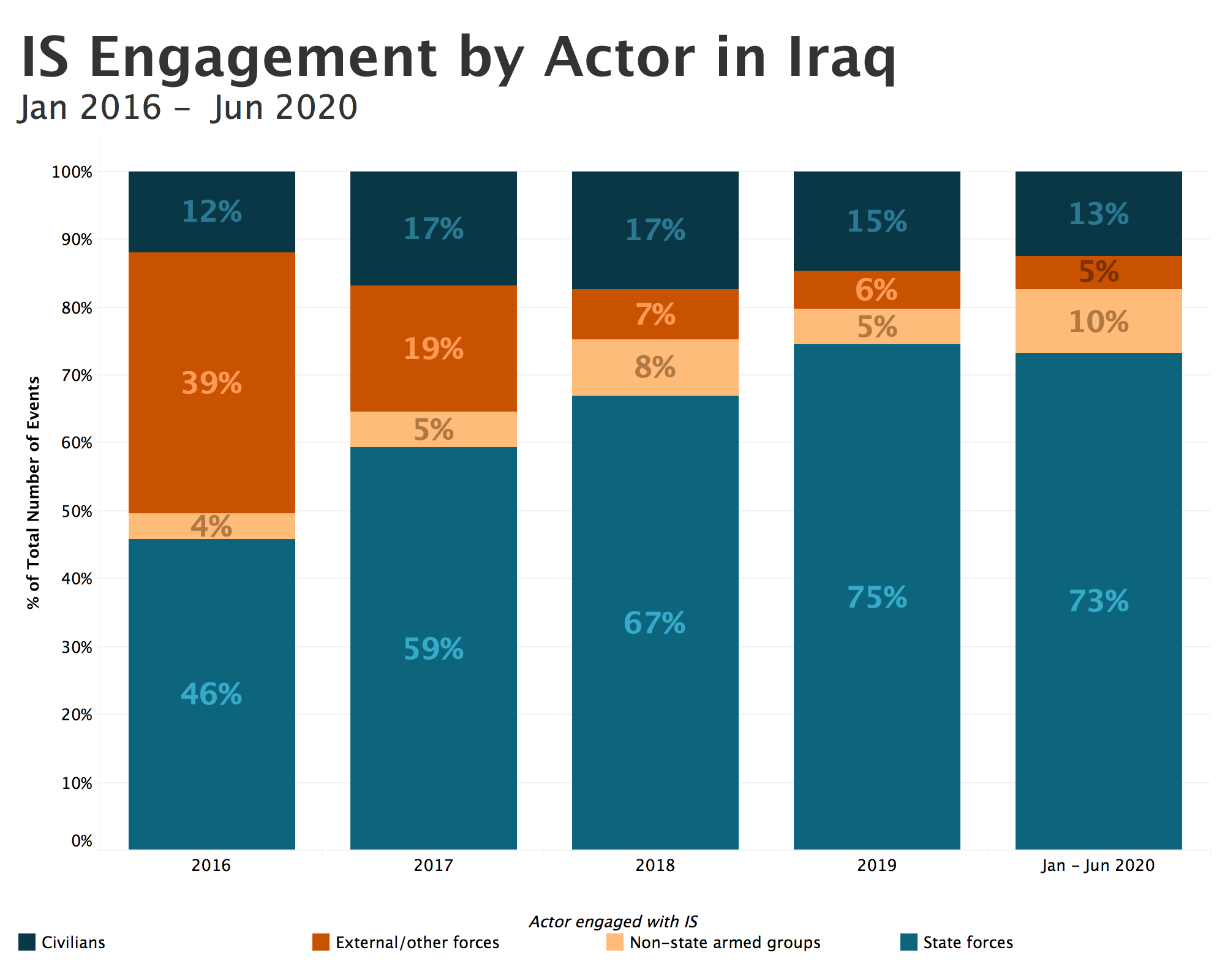

In general, in Syria and Iraq, IS has focused on dissolving the relationship between civilians and state forces, and has increasingly engaged state forces directly in an effort to weaken them. In Sunni-majority areas, IS fighters have a history of using insurgent tactics to target Shiite communities in order to spur sectarian violence, with the intention of sowing widespread distrust they can then exploit (Washington Institute, October 2016). IS now appears to be engaging in similar strategies: the group’s campaigns are targeting Kurdish areas of northeastern Syria, such as Deir-ez-Zor, where IS has sought to undermine the QSD by attacking the local Arab population, discouraging the population from collaboration with Kurdish and pro-Iranian militias (Syria Direct, 31 May 2020). Further weakening the QSD allows IS to shape the operating environment to its advantage, giving the organization space to grow. IS has also perpetrated several attacks on anti-IS Sunni communal leaders, maintaining a presence and provoking fear in Sunni communities that might be tempted to reject the group. Indeed, in Iraq, IS’s engagement has shifted from less than half of events involving state forces in 2016, to 73% thus far in 2020 (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Prison breaks were also an early part of IS’s initial rise, and will likely be part of any new resurgence, in particular due to IS’s potential recruitment difficulties. IS encouraged prison breaks in IS’s statement on the coronavirus pandemic (Jihadology, 19 May 2020). The spread of the coronavirus has made it more difficult for groups like QSD to properly guard prisons, even as IS has gradually regained power (Inherent Resolve, 8 May 2020). Initial prison breaks — such as in Al-Hasakeh in QSD territory — indicate early attempts to exploit QSD’s distraction with the pandemic to achieve these goals (International Crisis Group, 11 October 2019).

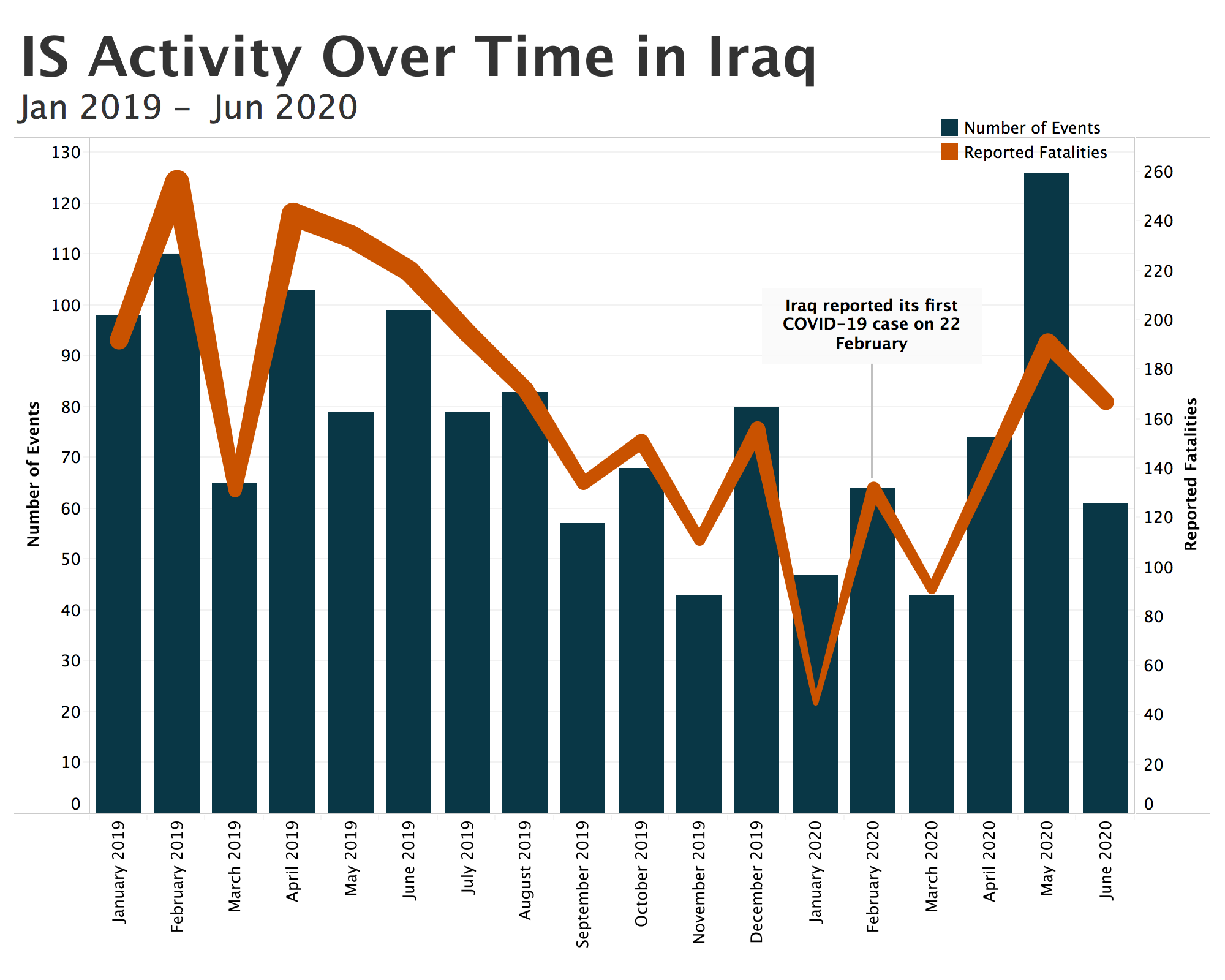

The coronavirus pandemic has generally allowed IS to further increase its activity, and, in some areas, IS has been ‘more lethal than COVID-19’ (Voice of America, 6 June 2020). In the four months since Iraq’s first coronavirus case, IS has increased its rate of attacks, killing more than 50 people (see Figure 7). Reports suggest that these attacks exploited large gaps in security force presence – gaps unlikely to close anytime soon (for more see ACLED’s COVID-19 Disorder Tracker (CDT) spotlight on IS).

Figure 7.

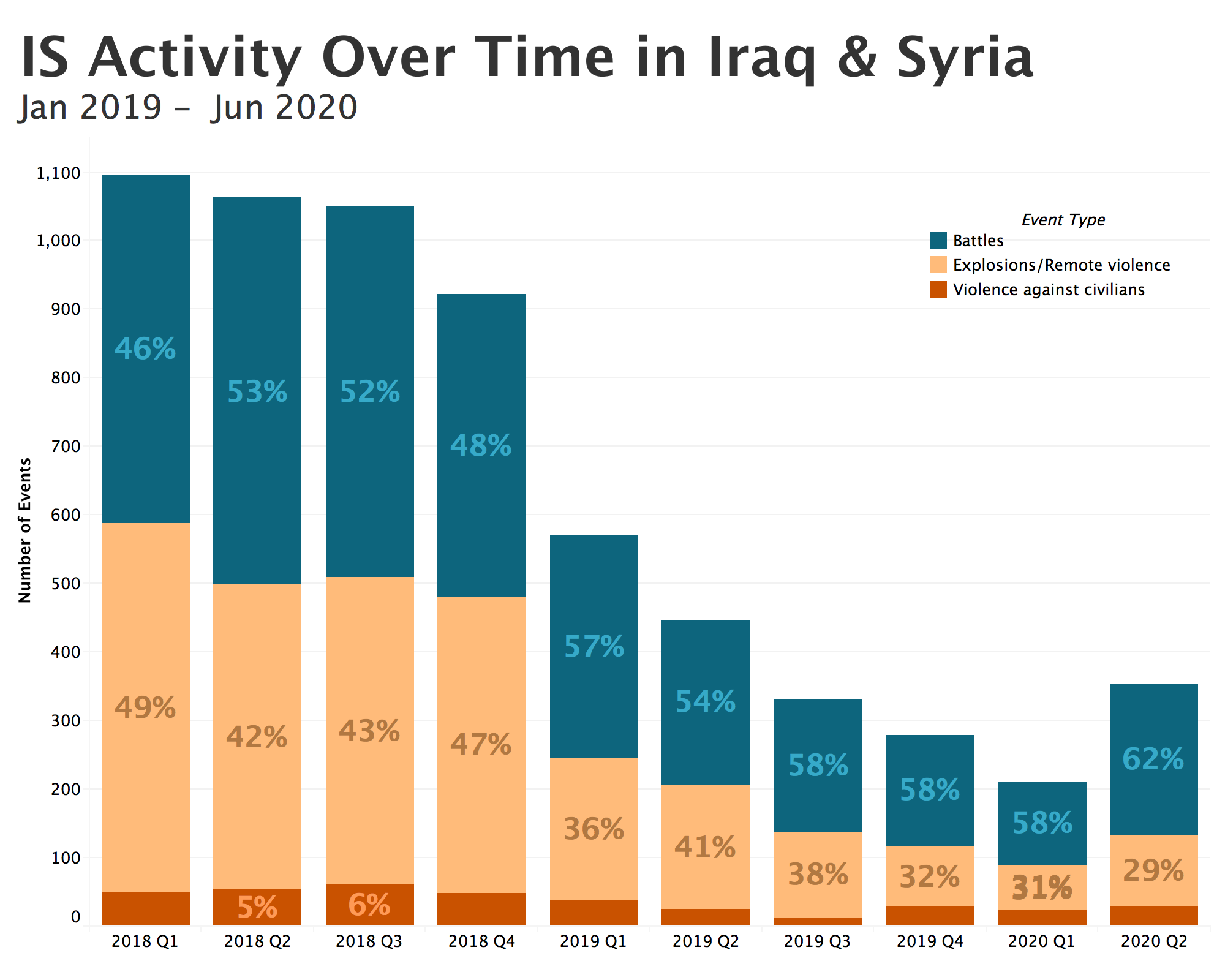

Importantly, isolated individual attacks by autonomous cells have been replaced in some instances over the past months by coordinated attacks (Twitter, 2 May 2020). In early May, IS began aggressive, complex, multi-stage attacks against ISF for the first time since their 2017 ‘defeat’ (International Crisis Group, 13 May 2020). While there does not appear to be a huge jump in their capability and level of sophistication writ large, the timing and target selection appears to have shifted in spring 2020. This tactical sophistication has not reached 2014 levels, but several developments – including an attempted suicide attack in Kirkuk on an intelligence headquarters – indicate growing capability and strength (DW, 22 May 2020). These operations underscore that IS maintains not only tactical, but functional strength: complex attacks require not only advanced hardware and know-how, but also undetectable intelligence networks and access to information (The Guardian, 24 May 2020). For much of IS’s last stand, a majority of IS-related events in Iraq were simple explosions/remote violence events (in yellow in the graph below) – either air or drone strikes against them, or remotely detonated IEDs and relatively low-cost, low-risk attacks perpetrated by them. However, over the first six months of 2020, complex armed clashes, largely with state forces (in teal in the graph below), have become IS’s modus operandi in Iraq and Syria (see Figure 8).

Figure 8.

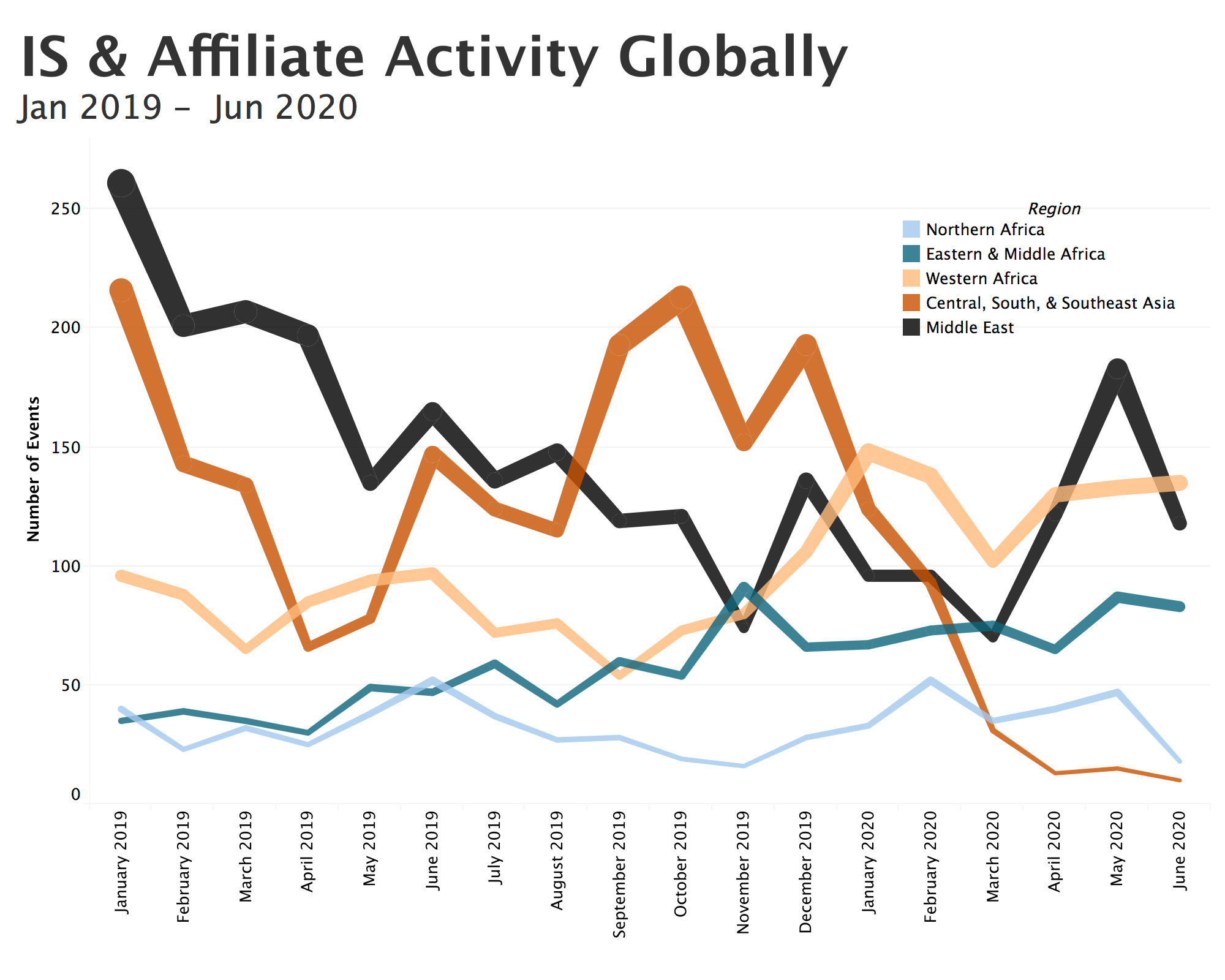

Finally, IS in 2020 has one advantage over its previous iterations: operational capacity beyond Iraq and Syria, and in fact across the Muslim world. An IS resurgence will not only take place in Iraq and Syria, though these core areas are crucial. Setbacks in its core territory will not necessarily impact IS provinces in Asia or Africa, where violence is rising. In West Africa, for example, attempts to exploit local conditions to gain territorial control are ramping up (Washington Post, 22 February 2020). This strategy might prove particularly advantageous to the group as the US considers withdrawing troops from the region (Washington Post, 21 January 2020), and will provide reputational and material gains for the IS organization at large (see Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Is this the resurgence?

To some extent, IS’s strength cannot be measured through a simple comparison to its past trajectory; contexts have changed and as a result, the way in which the group behaves and evolves has changed. However, applying IS’s former developmental arc to its current status, IS does not have the strength it did in its previous peak in 2015; it is also not nearly as capable as the period immediately preceding its peak, around 2014. US Lieutenant General Pat White notes that IS’s tactical movements are “inconsistent” with IS’s past prowess in Iraq, lacking complex military operations consisting of multiple simultaneous prongs of attack and relatively sophisticated weaponry. For now, IS “no longer possess[es] the capability, the leadership, or the finances to be the [IS] of old” (Inherent Resolve, 8 May 2020). Despite its fierce attempt to take advantage of conditional shifts in Iraq in April and May, the offensive seems to have – for now at least – died down, making it the shortest offensive in years. It is unclear whether IS has the logistical prowess to successfully take advantage of these conditions over a more sustained period.

However, whether IS is ‘living up to 2014’ is not the paramount question: it is crucial to understand shifts in IS behavior – both qualitative and quantitative – even if they do not indicate an immediate readiness to become the IS which terrified the world in 2014 (International Crisis Group, 13 May 2020). It is clear IS is not as strong as it once was, but also that the group remains able to skillfully exploit shifting historical conditions to its advantage. While current conditions do not allow the group to carry out a 2014-style campaign of terror, IS’s position relative to the period immediately following its defeat has improved, and the operational arena is largely shaped in its favor. If one thing remains consistent in IS’s trajectory, it is that the group prioritizes flexibility, patience, and longevity. While IS is not yet resurging, it is steadily and strategically laying the groundwork for the next phase of its evolution.