Political disorder1The term disorder is used in this report to refer to all political violence and demonstrations. This effectively includes all events in the ACLED dataset, minus Strategic developments — which should not be visualized alongside other, systematically coded ACLED event types due to their more subjective nature. For more on Strategic developments and how to use this event type in analysis see this primer. in Europe2ACLED has published new data covering 37 European countries and territories. For more, see this press release. Ten of those new countries are featured here. is largely driven by social movements. Most democratic governments across the region have enabled a robust protest culture to form around a host of issues, ranging from the Yellow Vest movement in France to climate change demonstrations in Sweden. At the same time, a turn towards illiberalism has stifled political freedoms in countries like Poland and Hungary.

The onset of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020 further shaped regional demonstration trends. While demonstrations initially declined across the region, ACLED records a subsequent uptick in anti-lockdown demonstrations against government measures to stem the spread of the virus. Many of these demonstrations were held by right-leaning and conspiracy-minded groups, such as Querdenken in Germany. In Italy, the pandemic response led to a significant number of prison riots.

Inspired by protests in the United States, demonstrations against racism and in support of the Black Lives Matter movement also spread across Europe. While demonstrations in the United States focused on systemic racism and police brutality, demonstrations in Europe highlighted the legacy of colonialism. Police violence against communities of color also motivated protesters in countries like France. Violence against Black and immigrant populations further spurred anti-racism demonstrations in Portugal.

Disorder in Europe is also linked to the far-left and far-right political divide. Groups from both sides engage in political violence and protest to promote their agendas. In countries like the Netherlands, far-right support for farmer protests — not always welcomed by the farmers themselves — has exacerbated existing polarization.

Lingering separatist sentiments have also been a source of disorder in places such as Northern Ireland and Spain. In Northern Ireland, sectarian tensions come to the fore during the marching season each year. In Spain, demonstrations calling for Basque and Catalonian independence persist.

ACLED’s expansion of coverage to all of Europe allows for data-driven analysis of these political disorder trends for the first time. This report reviews the new data and examines the 10 cases highlighted above.

All data can be accessed through the Data Export Tool and Curated Data Files.

![[cover] NI_black(100)](https://acleddata.com/acleddatanew/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/cover-NI_black100.png)

Political Disorder in Europe: 2020

Please click through the drop-down menu below to jump to specific cases.

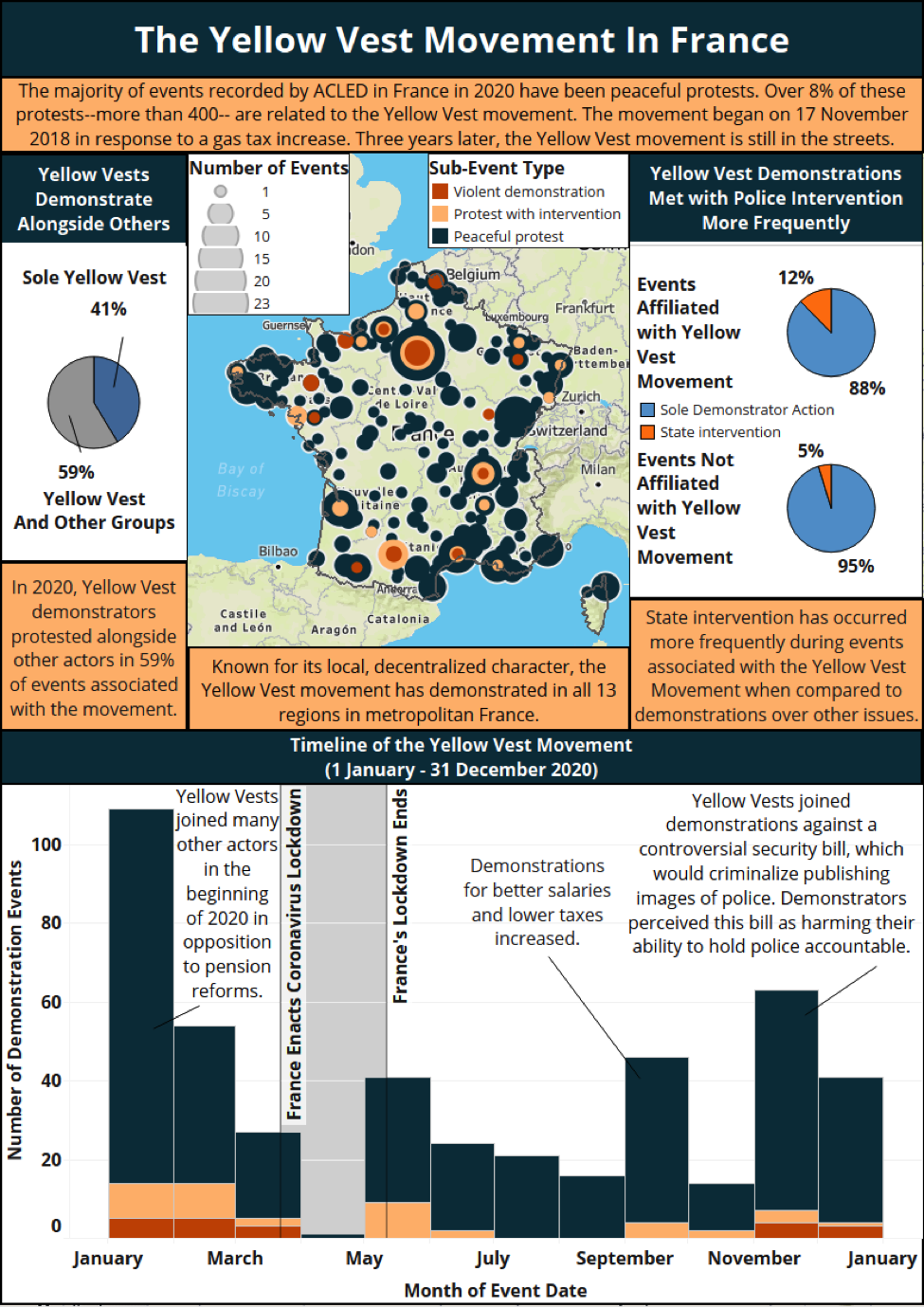

Major protests have broken out in France over reforms implemented by successive governments in various sectors, including changes to pension schemes as well as changes to labor laws. In 2017, arriving amid economic stagnation, President Emmanuel Macron abolished the wealth tax, increased gas taxes, and carried out pension reforms. On 17 November 2018, protesters distrustful of politicians and frustrated by the rising cost of living took their grievances to the streets, calling themselves the Yellow Vests (Gilets Jaunes) after the high-visibility safety vests they wear. They organized without the aid of unions or other organized political groups, adopting a decentralized structure that allows anyone to join by simply putting on a yellow vest, which many motorists already own. The movement, rooted in an anti-elite ideology opposed to growing inequalities, spread quickly due to its leaderless organization.

Yellow Vest demonstrators are still in the streets. Over the course of 2020, ACLED records over 400 demonstrations affiliated with the movement. Yellow Vest demonstrators were active across all 13 regions in metropolitan France. Only 10% of demonstration events took place in the capital, Paris, and these demonstrations have occurred in villages with fewer than 1,000 inhabitants, such as Glisy. In the early days of the movement, some demonstrations in larger cities became violent, leading authorities to cancel subsequent events (Europe 1, 16 November 2019). Since then, Yellow Vest demonstrations have remained largely non-violent. In 2020, 96% of Yellow Vest demonstrations were peaceful.

Although the level of violent or destructive activity at demonstrations associated with the Yellow Vest movement does not differ from all other demonstrations in France, Yellow Vest demonstrations were met with greater intervention by state forces in 2020. ACLED data indicate that 12% of all Yellow Vest demonstrations were met with police intervention, compared to only 5% of other demonstrations.

Yellow Vest demonstrators have grown frustrated with the government’s efforts to portray the movement as violent. They have often aligned themselves with other social and political movements in order to demonstrate against police violence. During June 2020, after the death of George Floyd in the United States, demonstrations over racial justice and police brutality against minorities were held across France. The “Truth for Adama” movement (Time, 11 December 2020) — an advocacy group calling for justice and truth regarding the death of Adama Traore, a Black man who died in police custody in 2016 — drew thousands of people to its demonstrations in Paris against French police violence (Liberation, 19 June 2020). Yellow Vest demonstrators have been present at many of these demonstrations.

In over half (59%) of demonstrations associated with the movement, the Yellow Vests demonstrated alongside other actors, including political parties, teachers, labor and environmental groups, health workers, and students. The movement’s political demands have expanded as they have joined in other demonstrations. Since January 2020, Yellow Vest demonstrators have protested alongside other groups against pension reforms, police violence, coronavirus-related measures, and the new security bill introduced in late 2020.

On 20 October 2020, the government introduced a new global security bill. Three articles within the proposed law sparked demonstrations: Article 21 allows police interventions to be filmed by their own mobile cameras and to be accessible to police officers; Article 22 expands the use of surveillance drones; and Article 24 criminalizes publishing images or videos where police can be identified. Demonstrations against the new security bill by people across broad sectors of society began on 17 November 2020. Demonstrators — joined by the Yellow Vests — have argued that the bill, if promulgated, would violate freedom of assembly and of the press as it makes it more difficult to protest and document police violence. Eventually, the government promised to rewrite Article 24, and the Council of State ruled for the second time that police could not use drones to surveil demonstrations in Paris (BBC, 22 December 2020).

Despite the ongoing demonstrations, Macron’s government has continued to pursue unpopular reforms amid a period of economic decline. French economic activity is estimated to have decreased by nearly 10% in 2020 due to the coronavirus pandemic (Banque de France, 15 December 2020). While Macron attempted to appease the Yellow Vest movement by raising the minimum wage by 0.99% and lowering income taxes for 17 million households in 2021 (RTL, 17 November 2020), this has not satisfied the demands of the demonstrators. Although pension reform has been delayed, the government has stated its intention to implement it in the new year. This suggests that the Yellow Vest movement is likely to remain active within the French political landscape in 2021.

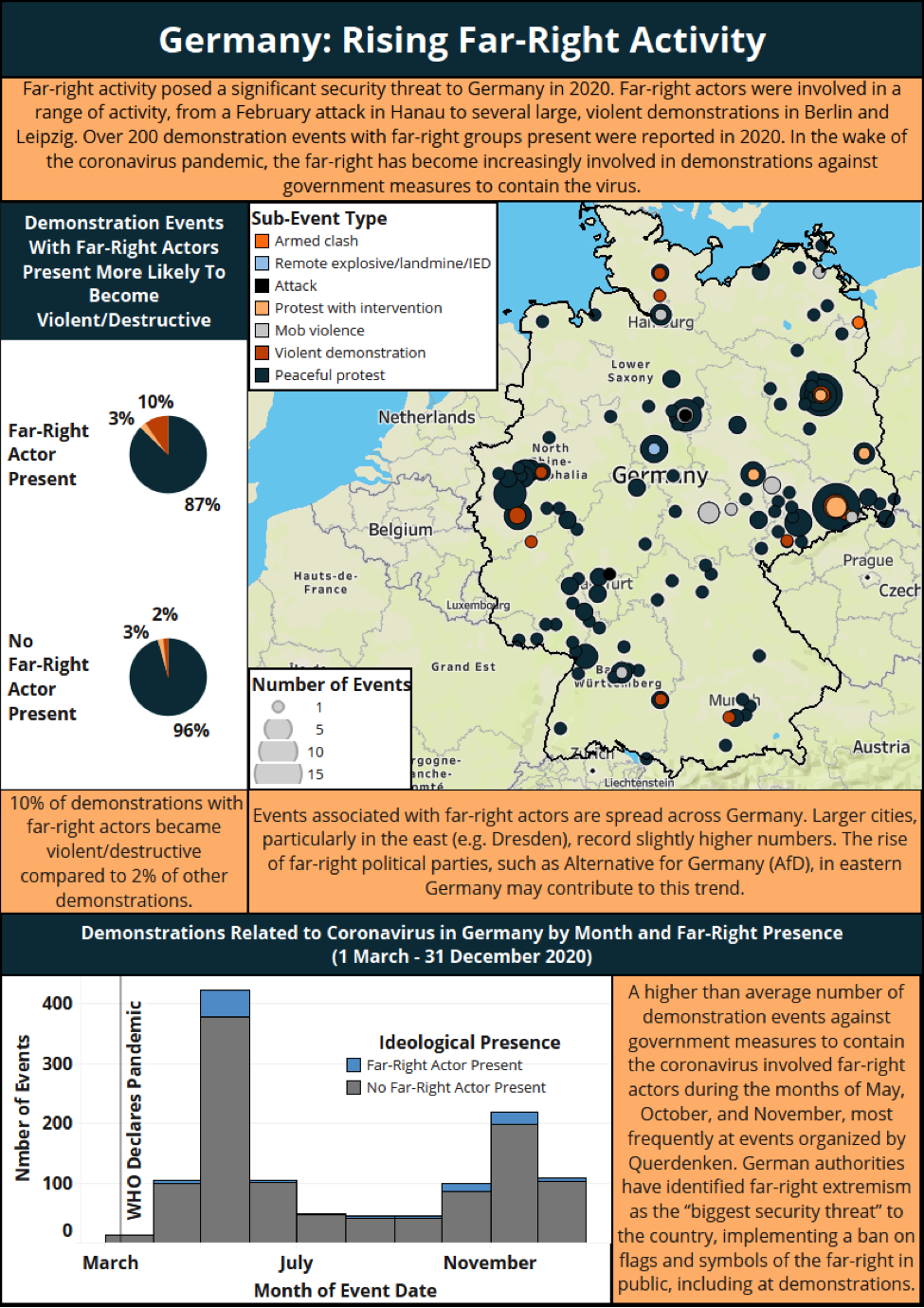

Far-right activity is on the rise in Germany. On 19 February 2020, a far-right extremist carried out shootings in two shisha bars in Hanau, leaving nine people — most of them migrants — dead (The Guardian, 20 February 2020). Although the gunman was a lone actor, multiple far-right chat groups involving German police forces and security agencies have been discovered since the attack. Over the past three years, there have been more than 1,400 suspected cases of German government employees holding right-wing extremist views among the military, police, and security agencies (BfV, September 2020). Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the far-right has become increasingly involved in demonstrations against measures to curb the spread of the coronavirus. Right-wing groups often use these demonstrations to further their own agenda, drawing parallels to their counterparts organizing against coronavirus restrictions in other parts of the world, such as in the United States.

ACLED records over 1,100 demonstrations against measures to curb the spread of coronavirus in Germany during 2020. One noteworthy development has been the increased infiltration of Querdenken, or ‘Lateral Thinking,’ demonstrations by the far-right. The Querdenken movement was founded in April 2020 in opposition to coronavirus protection measures. It initially attracted a range of people, including those worried about a limitation of their basic rights, anti-vaccination activists, and conspiracy theorists, such as QAnon followers. Over the past few months, far-right actors have successfully influenced the movement by capitalizing on demonstrators’ distrust of and dissatisfaction with the government to advance their own agenda (DPA, 21 December 2020). This success has caused concern among German government officials (The Washington Post, 9 December 2020).

Over 140 demonstration events associated with Querdenken were reported in 2020. Of these demonstrations, 21 have involved far-right actors, and 18 of these have taken place since October — pointing to the recent increase. The involvement of far-right actors has increased the likelihood of violent or destructive activity at these events. For example, on 29 August, 38,000 people — including various far-right groups, such as the Identitarian Movement, the Steeler Boys, Reich Citizens, and The Right — assembled in Berlin for a Querdenken demonstration that ultimately turned violent. During the demonstration, rioters broke police barriers and attempted to storm the Reichstag while carrying Reichsflaggen — flags used during 1871, 1918, and the Third Reich. This incident was seen as a turning point and a symbolic victory for the far-right, making their influence on the Querdenken movement widely visible (The Guardian, 29 August 2020). On 7 November, 20,000 to 45,000 Querdenken demonstrators — including far-right groups such as Pro Chemnitz and the Nationalist Democratic Party of Germany (NPD) — assembled in Leipzig (France24, 8 November 2020). The demonstration turned violent, with rioters throwing stones at police. Thirty-two journalists were attacked and injured by demonstrators. It is now estimated that nearly one-third of Querdenken demonstration participants belong to the far-right (Tagesschau, 5 December 2020).

In July 2020, while presenting the annual domestic intelligence security report, Federal Interior Minister Horst Seehofer identified far-right extremism as the “biggest security threat” to the country (DW, 9 July 2020). In light of this threat, and in response to the rising participation of the far right in Querdenken demonstrations, the State Office for the Protection of the Constitution of the federal state Baden-Württemberg announced in December 2020 that it has put the movement under surveillance on the grounds of it being “infiltrated by extremists” (DW, 9 December 2020). Other state-level measures aimed at weakening the far-right include the ban on Reichsflaggen in public, including at demonstrations, by the city-state of Bremen. In addition, the federal government has placed bans on the right-wing extremist groups Combat 18 (BBC, 23 January 2020), Nordadler (BMI, 23 June 2020), the Sturmbrigade 44 (DW, 1 December 2020), and the Reich Citizens’ branch United German Peoples and Tribes (DW, 19 March 2020).

As the pandemic wears on, the far-right is likely to continue or to increase its involvement in demonstrations against coronavirus restrictions in the new year, capitalizing on people’s discontent over government policy. The extent to which the government will devise effective measures to counter the threat of far-right violence remains to be seen. Public criticism of the government will likely be amplified with the federal elections scheduled for September 2021 and the extension of coronavirus measures that fuel discontent.

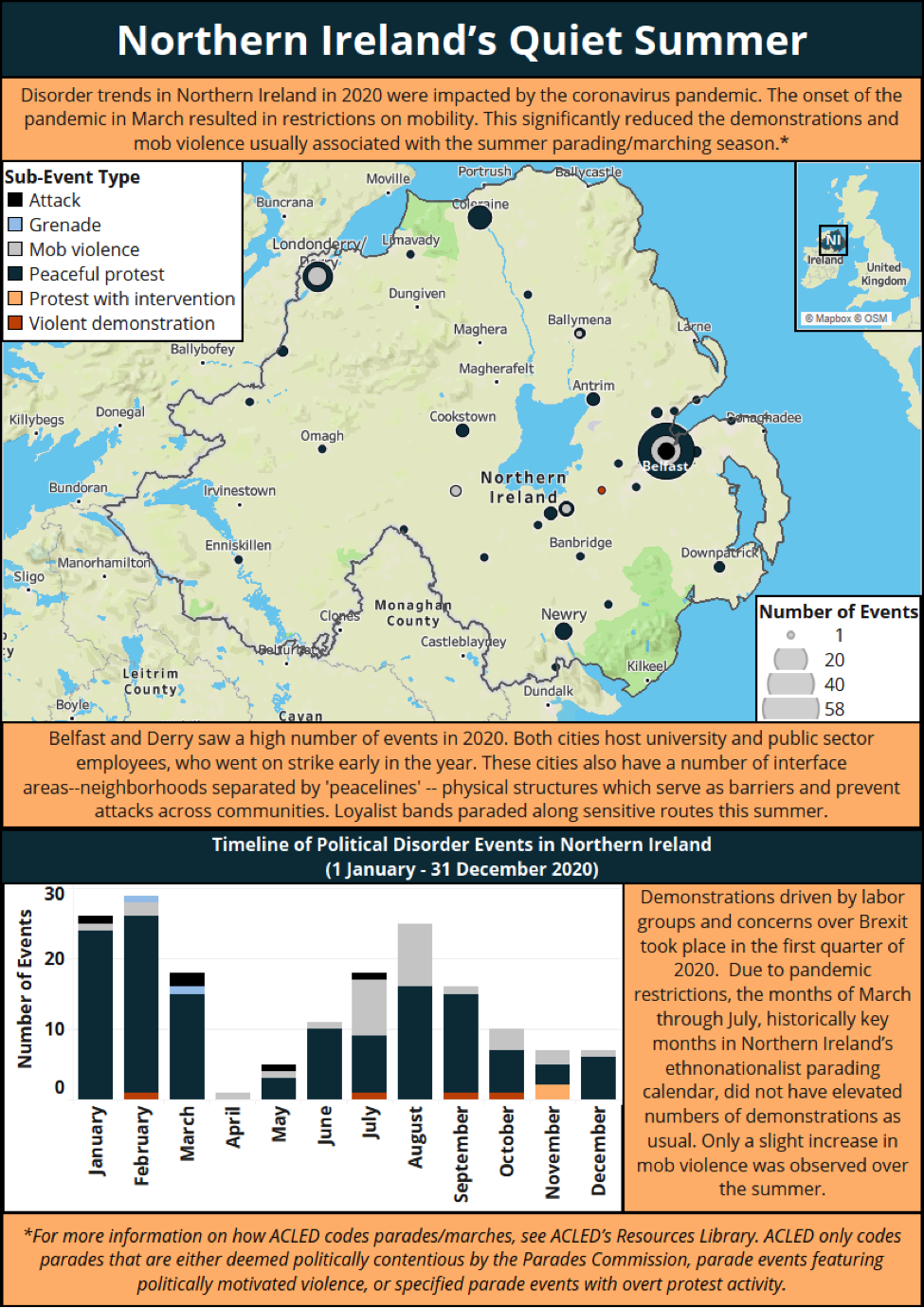

ACLED recorded over 135 demonstration events in Northern Ireland during 2020. Early in the year, demonstration activity spiked due to tensions over the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the European Union as well as bouts of university and public sector strikes. However, the onset of the coronavirus pandemic in March led to significant restrictions on public gatherings, resulting in a dramatic reduction in the number of demonstrations, as well as mob violence, typically associated with Northern Ireland’s parading/marching season.3Parading and marching are used interchangeably in reporting. For more information on how ACLED codes parades/marches, see this Northern Ireland methodology brief. ACLED only codes parades that are either deemed politically contentious or “sensitive” by the Parades Commission, parade events involving politically motivated violence, or parade events with overt protest activity. Nevertheless, tensions remain high, with an increase in threats by militias4Non-state armed and organized violence in Northern Ireland is dominated by militia groups that fight along sectarian ‘Republican’ and ‘Loyalist’ lines, and stage attacks on state forces and members of other armed groups. These groups are often referred to as ‘paramilitary groups’ by others. However, ACLED uses the term ‘paramilitary’ to refer to groups with a direct link to the state. In this way, these groups, which do not have direct, formal links to a state, are not categorized as such by ACLED; rather, they are categorized as ‘political militias’. For more, see this Northern Ireland methodology brief. against politicians and journalists (Belfast Telegraph, 28 November 2020).

The year 2020 began with a newly devolved government in Northern Ireland under the “New Decade, New Approach” power-sharing agreement with the Democratic Unionist Party’s Arlene Foster as First Minister and Sinn Féin’s Michelle O’Neill as Deputy First Minister of the executive (NI Executive, 9 January 2020). Brexit has deepened the fault lines that have existed between the governing Unionist and Nationalist political parties, and Republican and Loyalist groups, since the 40-year conflict known as the ‘The Troubles.’ It has renewed the risk of violence over contested borders and threatens to further harden ethnonationalist identities (Foreign Policy, 14 September 2020).

On 31 January 2020, the day the United Kingdom officially left the European Union, the Continuity Irish Republican Army (CIRA) attempted to blow up a ferry sailing from Northern Ireland to Scotland. The bomb was intercepted by the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) (The Guardian, 6 February 2020). At least four demonstrations by Border Communities Against Brexit — attended by the nationalist political party Sinn Féin — also occurred on the eve of Brexit. Though the pandemic quickly overshadowed these concerns, Brexit also increased the threat of economic shocks and instability in Northern Ireland (Guardian, 6 January 2021).

In addition to concerns over Brexit, labor conditions fueled many (over 40%) of the demonstrations recorded in Northern Ireland. These were most frequently organized by the Northern Ireland Public Service Alliance (NIPSA) and by striking university staff of Queens University and Ulster University (BBC, 4 February 2020; Belfast Telegraph, 25 February 2020).

Although demonstrations in Northern Ireland waned after pandemic restrictions were imposed on 28 March, they began to pick up again in May as protests were held after George Floyd was killed by police in the United States. Several demonstrations associated with the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement were held in Belfast and Derry in June, mirroring the spread of the movement to Dublin, London, and other European cities.

Although protesters associated with BLM in Belfast and Derry respected social distancing measures in light of new coronavirus legislation, the PSNI issued 70 fines and sought out the organizers of the demonstrations in order to press charges. The unusually harsh police response to the peaceful demonstrations was subject to a Police Ombudsman investigation, an independent public complaints body set up in 1998 to bolster police accountability and address the history of uneven policing of Nationalist/Republican and Unionist/Loyalist communities. The investigation concluded that the distribution of fines to BLM protesters was “unfair” when compared to the lack of such a response to the “Protect our Monuments” demonstration in Belfast on 13 June. The latter demonstration was organized by Loyalists to protect and “defend” war memorial statues from the threat of damage by protesters associated with BLM (PONI, 22 December 2020; BBC News, 13 June 2020).

Commemorations and sectarian demonstrations in Northern Ireland are often at risk of turning violent. Belfast typically reports the most parade-related violence during the annual marching season, beginning in March and peaking in July. During the marching season, cities and towns host large walking processions led by Loyalist orders and marching bands to commemorate key historical dates in UK military history. Parades are also held by Nationalist/Republican organizations and marching bands (although to a much lesser extent) to commemorate key dates of Irish independence and resistance. Of the estimated 4,000 parades that occur annually in Northern Ireland, the vast majority are peaceful (Parades Commission, 2020). Parade-related protest, controversial bonfires, and the subsequent risk of rioting remains concentrated in Belfast’s interface areas. These are single-identity residential zones often separated by ‘peacelines’ — physical structures erected to serve as barriers and to prevent attacks across conflicting communities (Cunninghman and Gregory, 2014).

Due to coronavirus restrictions, last year’s marching season was notably curtailed. The Orange Order, the largest parading actor in Northern Ireland, announced the cancellation of its usual Twelfth of July Parades, 18 of which are held annually in locations around Northern Ireland (BBC, 6 April 2020). The Apprentice Boys of Derry cancelled their largest demonstration as well (Derry Journal, 15 May 2020). Though a number of Loyalist bands still engaged in limited parading, overall sectarian demonstrations (including parades along “sensitive” or contested routes,5The type of parade that meets the threshold for inclusion in ACLED data. and protests of a sectarian nature) fell well below the recent annual average with only a fraction — fewer than 30 — taking place during 2020, and with only minor incidents of mob violence.

Overall, the coronavirus pandemic significantly impacted historical patterns of demonstrations and violence in Northern Ireland in 2020, particularly leading to a decline in parades. Looking to 2021, the combined effect of the pandemic and Brexit will likely lead to further economic uncertainty for Northern Ireland. It remains to be seen how this uncertainty will impact demonstration and disorder in the coming years.

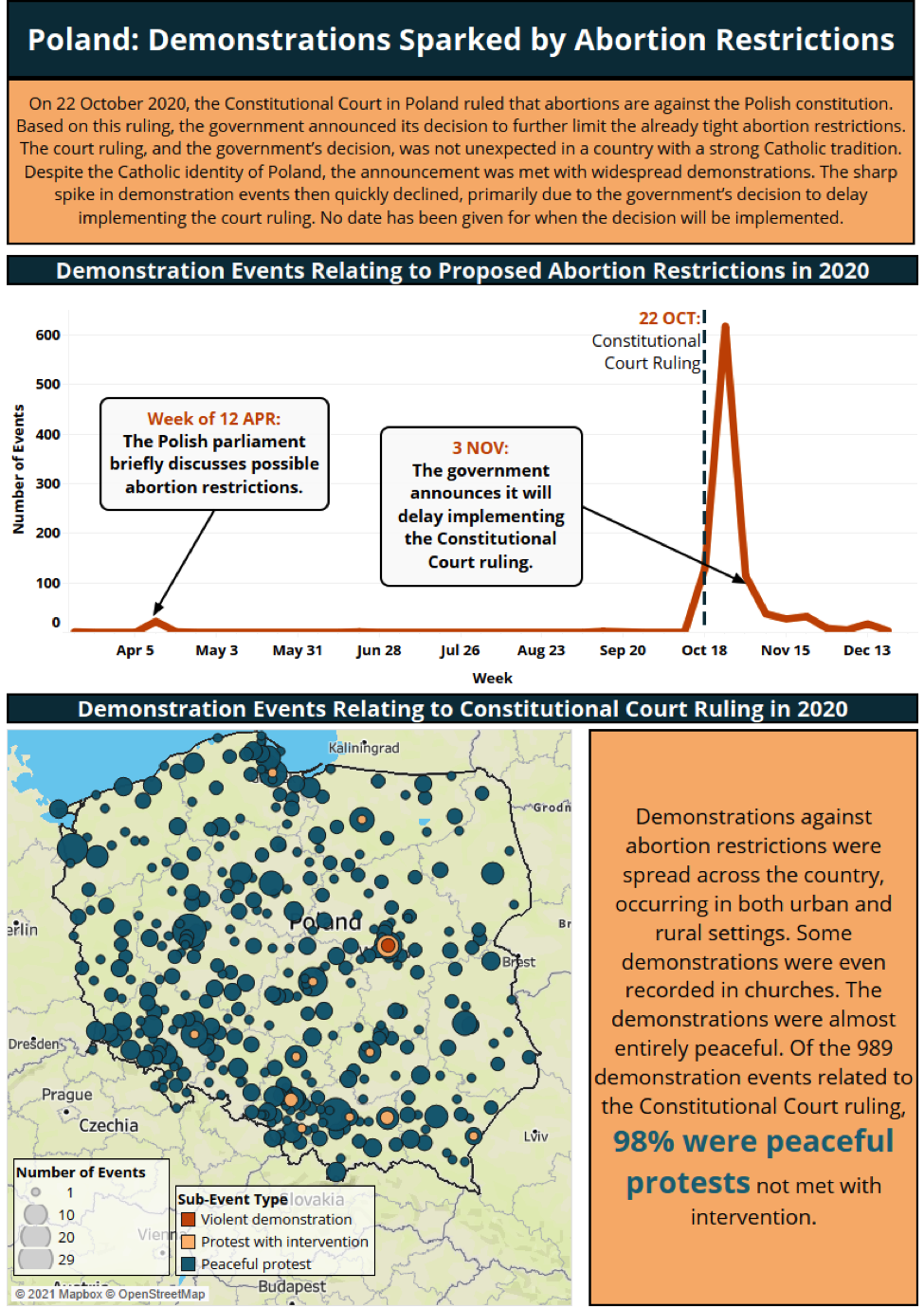

On 22 October 2020, the Constitutional Court in Poland ruled that abortions are unconstitutional. Based on this ruling, the government announced its decision to further limit already strict abortion restrictions, only allowing abortions to be carried out in situations where the mother’s life is in danger or where the pregnancy resulted from incest or rape. The decision would prohibit abortions in cases where the fetus is physically disabled. These issues of women’s rights and government intervention, however, are only the tip of the iceberg of a much deeper divide within Polish society.

Poland is a country with a strong Catholic and nationalist tradition in its politics. The ruling Law and Justice party (PiS) has made nationalist and Christian-based values the cornerstone of its political agenda. While abortion has long been a controversial issue, and actively restricted, this party’s platform interprets abortions as murder.

Nevertheless, a large part of Polish society advocates liberal, secular and pro-Western values over nationalist ones. This represents a large part of political opposition to the current government. Their attitudes, however, do not mean a rejection of Poland’s Catholic identity or patriotism. Rather, it is a manifestation of anger with the alleged authoritarian tendencies of government power and the strong influence of clergy on state affairs. This opposition has been further aggravated by recently revealed cases of sexual abuse by high-ranking officials.

Even before the court ruling itself was announced, spontaneous protests erupted across the country during the deliberations. Women led the demonstrations calling for greater women’s rights and opposing the decision once it came down from the court. Since 19 October, ACLED records 990 demonstration events relating to abortion restrictions. The demonstrations have been large, and have occurred in both urban and rural settings, with some events even taking place inside churches (New York Times, 30 October 2020).

Nearly all demonstrations over abortion restrictions have been peaceful: approximately 98% of all events recorded since October have been non-violent protests without intervention. Only 22 protest events were met with intervention during the same time period. The limited number of violent demonstrations that took place were due to clashes with law enforcement. Although relatively rare, these violent events gained attention in domestic and international media.

Counter-demonstrations supporting the restrictions have also been recorded, though in much smaller numbers. Most of these demonstrations were organized by Catholic and nationalist groups. Aside from demonstrations, some actions in support of the restrictions, including online campaigns and special prayers during religious services, have been reported.6 These online campaigns and prayer events are not recorded in ACLED data.

Following a peak during the week of 25 October, the number of demonstration events over abortion laws have since decreased. One explanation for this trend is the worsening coronavirus outbreak in the country. However, it is likely that demonstrations decreased also partly due to the government’s decision not to immediately implement the court decision; no date has been given for when the decision will be implemented (New York Times, 4 November 2020).

While the government’s decision to delay implementing the court ruling may have significantly reduced the number of demonstration events, if Warsaw decides to ignore both domestic and international criticism in order to move forward with new restrictions, demonstrators are likely to return to the streets.

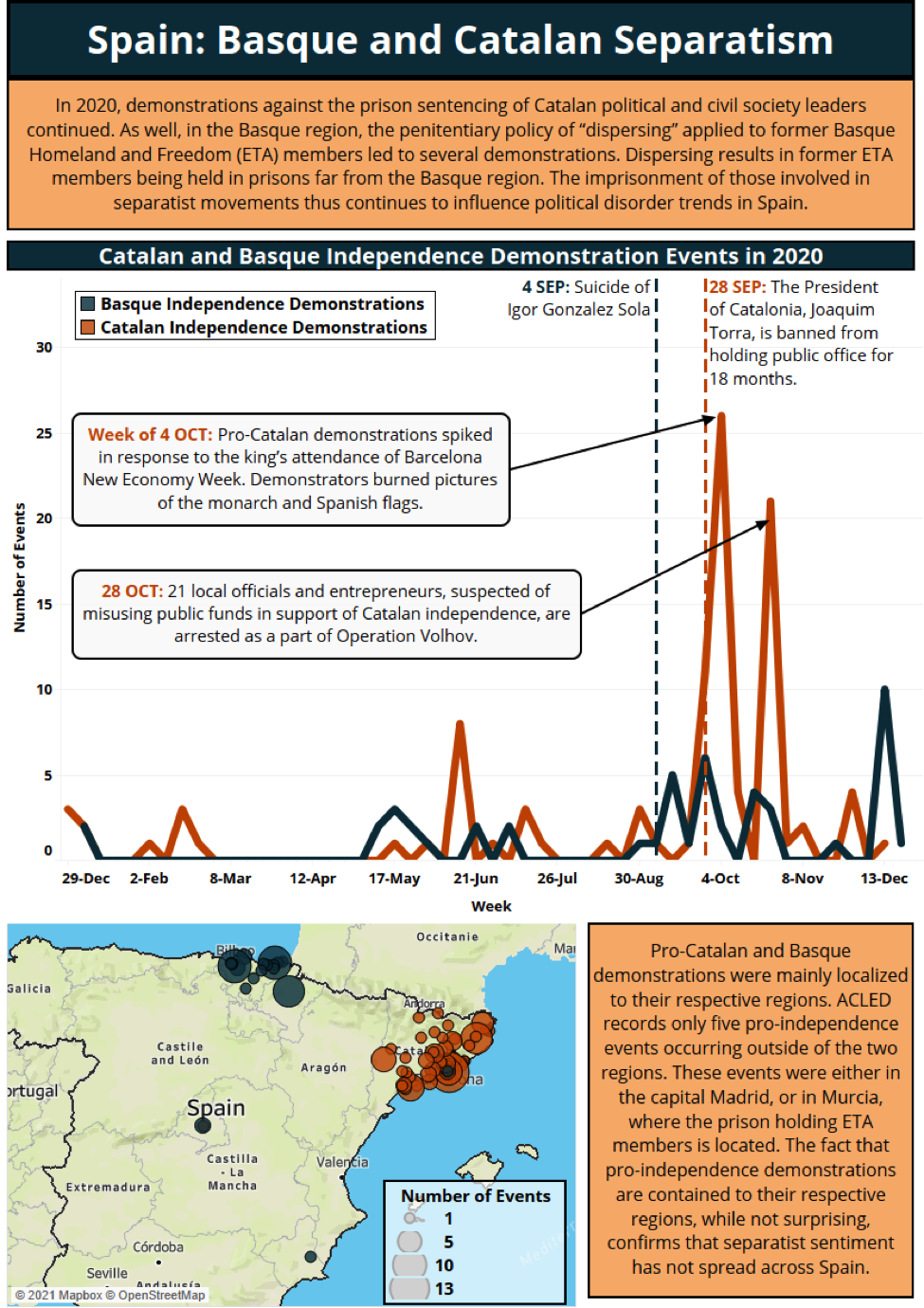

Despite the coronavirus pandemic, the number of public demonstrations in support of the Catalan independence movement has remained high in Spain since the beginning of 2020. Civil society actors continue to organize protests to demand Catalonia’s independence and to call for Catalan leaders to be released from prison. Demonstrations in the Basque region have also continued, though with less frequency. These latter demonstrations center on demands to transfer imprisoned former members of the Basque Homeland and Liberty (ETA) group to prisons in the Basque region, suggesting that the reconciliation process in the Basque conflict has not yet been fully realized.

On 14 October 2019, the Spanish Supreme Court ruled against two civil society leaders and nine Catalan separatist officials, finding them guilty on the grounds of sedition following the Catalan Independence Referendum and the unilateral Declaration of Independence in October 2017. Prior to the referendum, the Spanish Constitutional Tribunal declared that the Referendum Law, approved in the Parliament of Catalonia on 6 September 2017, violated the supremacy of the Spanish constitution, national sovereignty, and the indissoluble unity of the nation (La Vanguardia, 18 October 2017). The announcement of the unilateral Declaration of Independence, supported by the illegal referendum vote, led to a series of legal repercussions that are still being protested by civil society groups in Catalonia. Last year, commemoration protests were held marking the anniversary of the Catalan Referendum and the general strike in October 2017, which had been called by civil society groups and trade unions to condemn police violence at polling stations to stop the referendum (The Guardian, 3 October 2017).

Opposition to the sentencing of Catalan political and civil society leaders, to nine to 13 years in prison, has continued since the ruling. Amnesty International has advocated for the release of two imprisoned Catalan civil society leaders — Jordi Sànchez and Jordi Cuixart — stating that their conviction “threatens rights to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly” (Amnesty International, 19 November 2020).

ACLED records 96 demonstration events in 2020 in support of Catalonia’s independence. These demonstrations have nearly all been peaceful. Pro-Catalan demonstrators have also demanded the freedom of several imprisoned Catalan leaders and have destroyed the national symbols of Spain during some events. These symbols include Spanish flags and pictures of King Felipe VI, whose televised address to the nation on 3 October 2017, in which he stated that Catalan authorities had violated democratic principles of the rule of law, sparked criticism from the Catalan independence movement (Elpais, 4 October 2017; BBC, 5 October 2017).

Catalan’s devolved powers were suspended in 2017 and direct rule, applying Article 155 of the Constitution, was implemented, dissolving the regional parliament. New elections were held on 21 December 2017. This was followed by almost five months of political deadlock. Eventually, an agreement between pro-independence political parties was reached during the second-round vote in the Catalan parliament after previously having failed to reach an absolute majority. The candidate of the pro-independence political party Together for Catalonia (JxCat), Joaquim Torra, was thus finally elected regional president in May 2018 and remained in office until September 2020 (ElMundo, 14 May 2018). Subsequently, ACLED data show two spikes in pro-Catalan demonstrations. The first occurred following the 28 September 2020 ban of Torra from holding public office for 18 months. The Supreme Court upheld a lower-court decision against Torra for disobeying the Central Electoral Board, due to his refusal to remove pro-independence symbols from public buildings during an election. The second spike was observed in October following the arrest of 21 local officials and entrepreneurs as a part of Operation Volhov. The detainees were arrested on grounds of misappropriation,misuse of public funds, and prevarication, amongst other charges connected with financing of the 2017 referendum and declaration of independence (Ara.cat, 30 October 2020).

Along with Catalan independence, the issue of Basque separatism persists. Since the ETA — an armed Basque separatist organization calling for the region’s independence — announced the definitive end to its armed activity in 2011, there has been an ongoing reconciliation and coexistence process in the region. During 2020, some civil society groups demanded a modification to the Penitentiary and Prison Policy applied to former members of the ETA, asking for some members to be transferred closer to the Basque region, and those with serious medical conditions to be released. These demands have driven demonstrations in the region, though at a lower rate than those recorded for Catalonia.

In 2020, ACLED records 47 demonstration events calling for Basque independence. In most cases, protesters demand an end to the dispersing policy, which has resulted in former ETA members being held in prisons far from the Basque region. The suicide in September of former ETA member Igor Gonzalez Sola, who was held in prison under this rule, brought the issue to the forefront in 2020. Sola had made two previous suicide attempts (Naiz, 5 September 2020). The EH Bildu political party and Sare network have suggested that the string of suicides and deaths among ETA prisoners is evidence of the failure of the Spanish penitentiary policy toward them (Elpais, 5 September 2020; EHBildu, 7 September 2020). Last year, demonstrations were organized to express support for Iñaki Bilbao, an ETA prisoner who started a hunger strike in prison in September 2020.

During the second half of December 2020, demonstrations were reported in the Basque region against the Supreme Court’s decision to retry the 2011 Bateragune case (PoderJudicial, 14 December 2020). The case originally resulted in the conviction of five members of the abertzale left, a social and political left-wing Basque nationalist movement, for trying to rebuild the illegal Batasuna Independentist Alliance, which had previously been banned because of its links to the ETA. The defendants filed an appeal with the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) complaining about the lack of impartiality of the panel that convicted them in 2011 (ECHR, 6 November 2018). Subsequently, the case was declared void after ECHR found the defendants’ right to a fair trial had been violated (ElMundo, 19 December 2020). Peaceful protests supporting defendants of the Bateragune case were reported in Catalonia, Navarra, and Galicia regions.

The Basque and Catalan separatist movements remain significant drivers of demonstration activity in Spain. The Catalan separatist movement continues to call for the release of Catalan political and civil society leaders convicted in 2019, while Basque civil society groups, unions, and political parties demand an end to the dispersing prison policy applied to former ETA members. Demonstrations related to calls for Basque and Catalan independence are likely to continue in the new year.

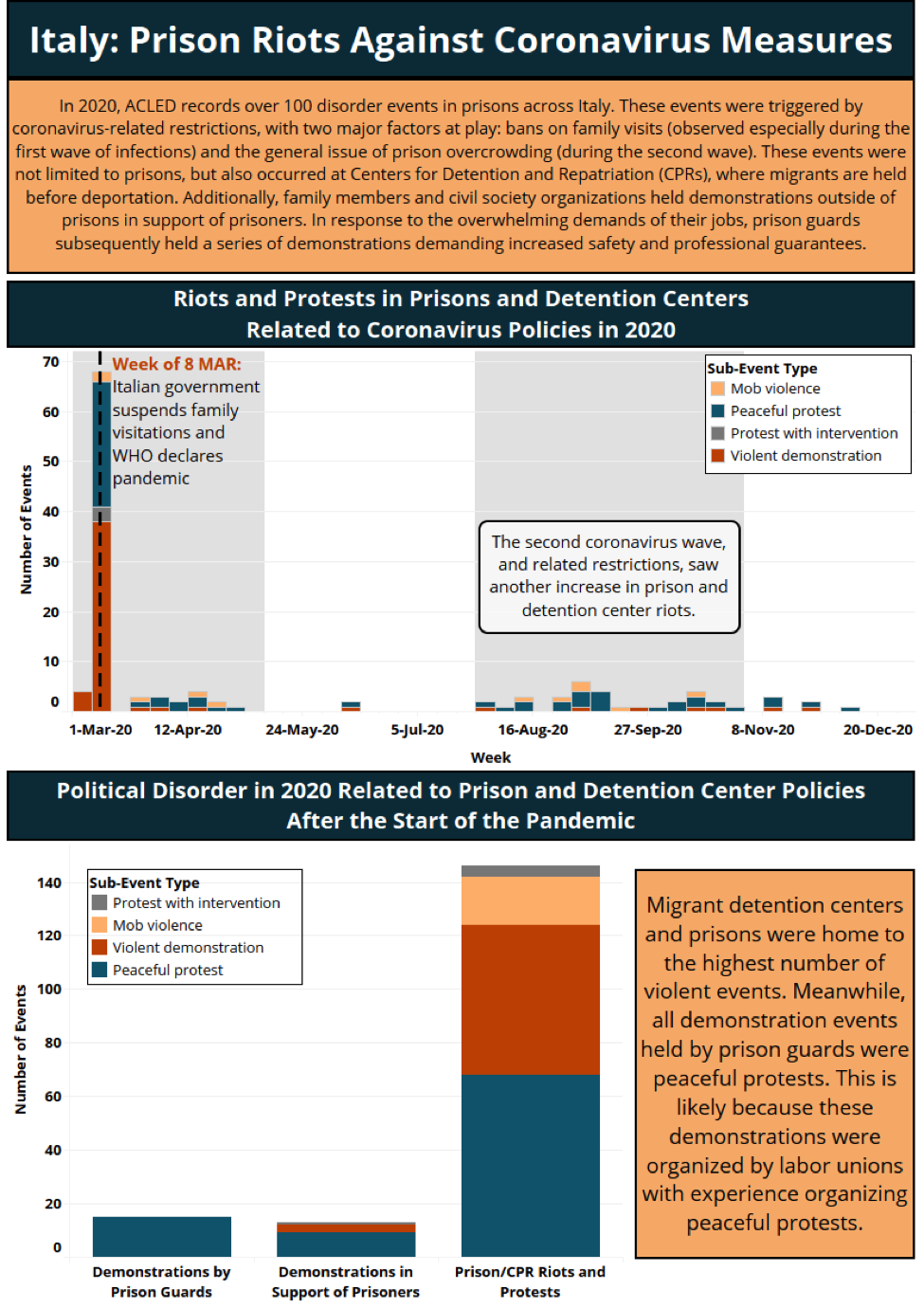

In 2020, demonstrations accounted for the vast majority of disorder in Italy, most of which can be linked to the coronavirus pandemic. By early March 2020, Italy recorded the second-highest number of coronavirus cases after China (BBC, 9 March 2020), prompting the government and regional authorities to deploy a variety of restrictions at different points throughout 2020. These measures rippled through detention facilities, fueling a series of violent demonstrations and mob violence events, in addition to peaceful protests. Between March and November 2020, ACLED records over 90 such events in prisons across the country, triggered by coronavirus-related restrictions. There were two major factors which led to these events: bans on family visits (especially during the first wave of infections) and the general issue of prison overcrowding (especially during the second wave). While initially contesting the loss of detainee rights, many prisoners later demonstrated over fears that living in poor conditions made them particularly susceptible to the virus. As indicated by a 2013 ruling from the European Court of Human Rights, which declared the country’s prison overcrowding a violation of basic rights, Italy has one of the largest prison populations in Europe (GI-TOC, 20 May 2020).

Prison riots, and demonstrations more largely, increased during the first half of March 2020, following, and in some cases anticipating, the announcement of restrictive measures by the government on 8 and 9 March. On 10 March, Italy became the first country in the world to implement a nationwide lockdown, forbidding all public gatherings, demonstrations, and non-essential travel, in an attempt to stave off the spread of the virus. Prior to this, the Italian Department of Penitentiary Administration had given autonomy to regional penitentiary authorities to suspend family visits to prisoners (Il Riformista, 3 March 2020). On 8 March, the government extended the recommendation to halt such visits to the entire country, and later made it mandatory as part of the lockdown, sparking a surge of inmate demonstrations (DPCM, 8 March 2020).

In March, ACLED recorded 27 peaceful protests, 49 prison riots, and two riots at Centers for Detention and Repatriation (CPRs) — detention facilities for holding migrants due to be repatriated (Osservatorio Migranti, 20 January 2021). These demonstrations were sparked by a temporary ban on in-person visits of detainees. In some cases, inmates demanded their sentences be commuted, that they be granted amnesty, or that they be temporarily placed under house arrest.

Many events in March were violent: detention facilities were ransacked and incurred heavy material damage, with furnishings and mattresses set on fire, and dozens of prisoners and prison guards sustaining serious injuries. In several facilities, prisoners stormed the prison infirmary amid the turmoil, with some taking drugs and later dying of overdoses. At least 13 prisoners were confirmed dead throughout the country as a result of such overdoses (Avvenire, 11 March 2020, Politico.eu, 30 March 2020).

During some of the incidents, inmates attempted to escape from their facility. Most notably, over 70 detainees broke out of a penitentiary center in the southeastern city of Foggia; all but one were later caught by police following a manhunt (Gnewslonline, 14 April 2020). During non-violent events, prisoners would routinely protest by hitting their cell bars with metallic objects, calling it “battitura,” or beating.

At the same time as the prison riots and protests, relatives of detainees held demonstrations demanding the reintroduction of family visits, and raising concerns about the state of infections in detention facilities. Like prisoners, these demonstrators also asked for the commutation of prison sentences, the granting of amnesties, or the placement of convicts under house arrest for the duration of the coronavirus pandemic. Most of these demonstrations, mainly peaceful in nature, took place outside of prison gates and often while a riot was ongoing inside the facility. ACLED records 13 such demonstration events organized by inmates’ relatives.

Prison guards and their trade unions reacted strongly to the riots, resulting in a spike in peaceful demonstrations held by guards in June. During these protests, prison guards demanded increased safety and professional guarantees after having faced down the riots. They asked for measures to be taken to mitigate the risk of coronavirus outbreaks in detention centers, in addition to an increase in the workforce and a substantial upgrade in prison facilities.

After the easing of coronavirus restrictions at the beginning of June 2020, prison riots substantially decreased. During the four months of less restrictive measures, from June to September, ACLED records five prison riots and 10 CPR riots. Peaceful protests by prisoners also decreased, with only seven events recorded from June to September.

Then, on 25 October, the government implemented new measures to address a second wave of coronavirus infections, this time on a differentiated regional basis, with further restrictions implemented nationwide at the end of December. This move was met by a slight increase in prison demonstrations, though smaller than the first spike. This time, the focal point of the demonstrations was on the issue of prison overcrowding. Prisoners claimed to feel unsafe and to fear for their health in a densely populated environment that facilitated the spread of the coronavirus.

Since 25 October, ACLED records four riots and five peaceful protest events by prisoners and detainees at CPRs. The majority of these events were related to the coronavirus pandemic. The events differed from the first wave of prison demonstrations in that they were predominantly peaceful protests, during which prisoners raised concerns about poor detention conditions.

Following the first lockdown, and as a way to address the lingering issue of prison overcrowding, the government has taken active steps to mitigate prison violence, reducing the number of inmates by expanding the prerequisites for house arrest, allowing prisoners with a remaining sentence of 18 months to apply for an early release, and granting permission to those in semi-freedom not to re-enter their cells at night (La Stampa, 15 December 2020). Some of these changes have been made by listening to the grievances of prisoners and their relatives in March. They proved to be relatively effective at containing a second wave of prison disorder in the fall.

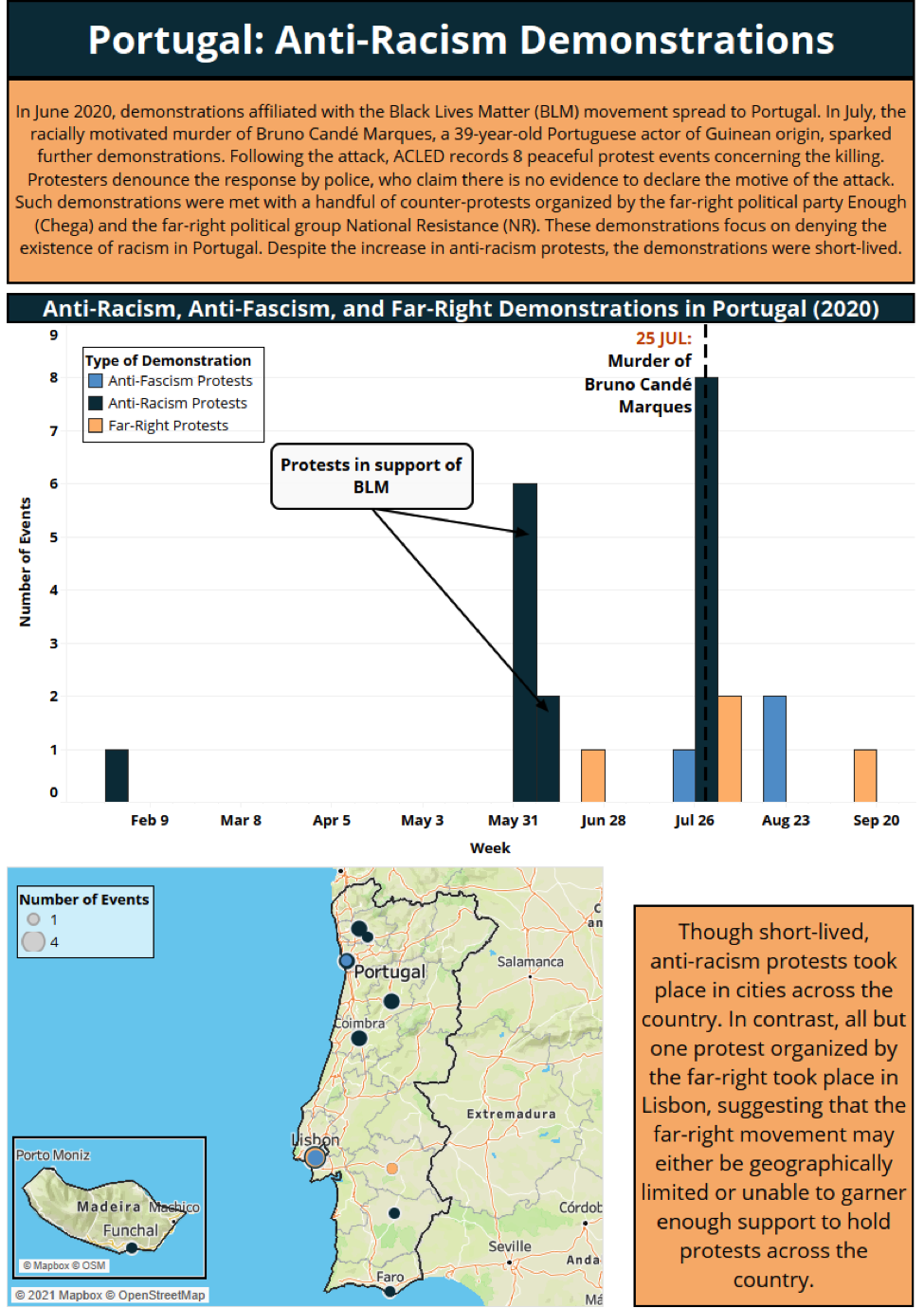

In June 2020, demonstrations associated with the Black Lives Matter movement spread from the United States to Portugal. Later that summer, anti-racism demonstrations surged after the racially motivated murder of Bruno Candé Marques, a Portuguese actor of Guinean origin. These demonstrations were followed by several counter-protests organized by Enough (Chega), a far-right political party, and other far-right political groups, such as National Resistance (NR), which deny the existence of systemic racism in the country. There is a large Afro-descendant population in Portugal which, along with the Roma population, has been the target of hate crimes and institutional racism in past years (OHCHR, November 2016).

At the beginning of 2020, ACLED records demonstrations across Portugal calling for justice and urging authorities to investigate a violent attack in Braganza on 20 December 2019 against Luís Giovanni dos Santos Rodrigues. The victim was a 21-year-old student of Cabo-Verdean origin, who died from his injuries on 31 January in the hospital. Activists organized protests to urge authorities to clarify what happened because, according to them, the state applies double standards in investigating crimes against immigrants (CmJornal, 11 January 2020). Anti-racism activists also raised concerns over the lack of societal, institutional, and media response to the death of a person from a different origin than Portugal. They question if reactions would have been different had the student been white (Noticias Ao Minuto, 6 January 2020; Sabado, 11 January 2020).

Some weeks later, on 1 February, around 300 people protested against police violence and racism after Cláudia Simões, a 42-year-old Black woman, alleged that a police officer used excessive force against her in a racially motivated attack during her detention in Amadora (TVI24, 23 January 2020). Following the March coronavirus lockdown, anti-racism protests spiked between 6 June and 10 June in support of the Black Lives Matter movement after George Floyd, a Black man, was killed by police in the United States on 25 May.

In July, Bruno Candé Marques, a 39-year-old Portuguese actor of Guinean origin, was shot dead by an elderly white man in Moscavide in an apparently racially motivated attack. According to family members, three days before the murder, the suspect threatened and insulted Candé using racists slurs (Visao, 26 July 2020). Following the attack, ACLED records eight peaceful protest events over the killing across a number of cities. Protesters carried banners condemning the Portuguese colonial legacy and calling for justice (Al Jazeera,1 August 2020). Protesters and activists condemn the response from police, who state that there is no evidence to determine the motive of the attack (Publico, 26 July 2020). On the contrary, SOS Racism, an organization dedicated to combatting racism in Portugal since 1990, asserts that there is “no room for doubt” that the murder was premeditated and racially motivated (SOSRacismo, 25 July 2020).

Since then, the European Network Against Racism (ENAR) reports that there has been a “rise of racist attacks [by] the far right in Portugal” fueled by far-right political discourse (ERNA, 3 September 2020). The communication states that hate speech has been escalating against human rights defenders and women parliamentarians. On 28 June, SOS Racism published a communication against demonstrations held by Enough (Chega), arguing that Enough (Chega) promotes hate speech against minorities, including the Black community and Roma people (SOS Racism, 28 June 2020).

While racial justice demonstrations took place in Portugal last year, these demonstrations were short-lived. Following both periods of demonstrations, ACLED records multiple far-right demonstration events, though these were equally short-lived. Still, it is likely that anti-racist activism will continue into the future: in January 2021, Marine Le Pen, leader of the far-right French National Union, visited Portugal to endorse André Ventura, Enough’s (Chega) presidential candidate, sparking a renewed round of protests against racism (Visao, 2021).

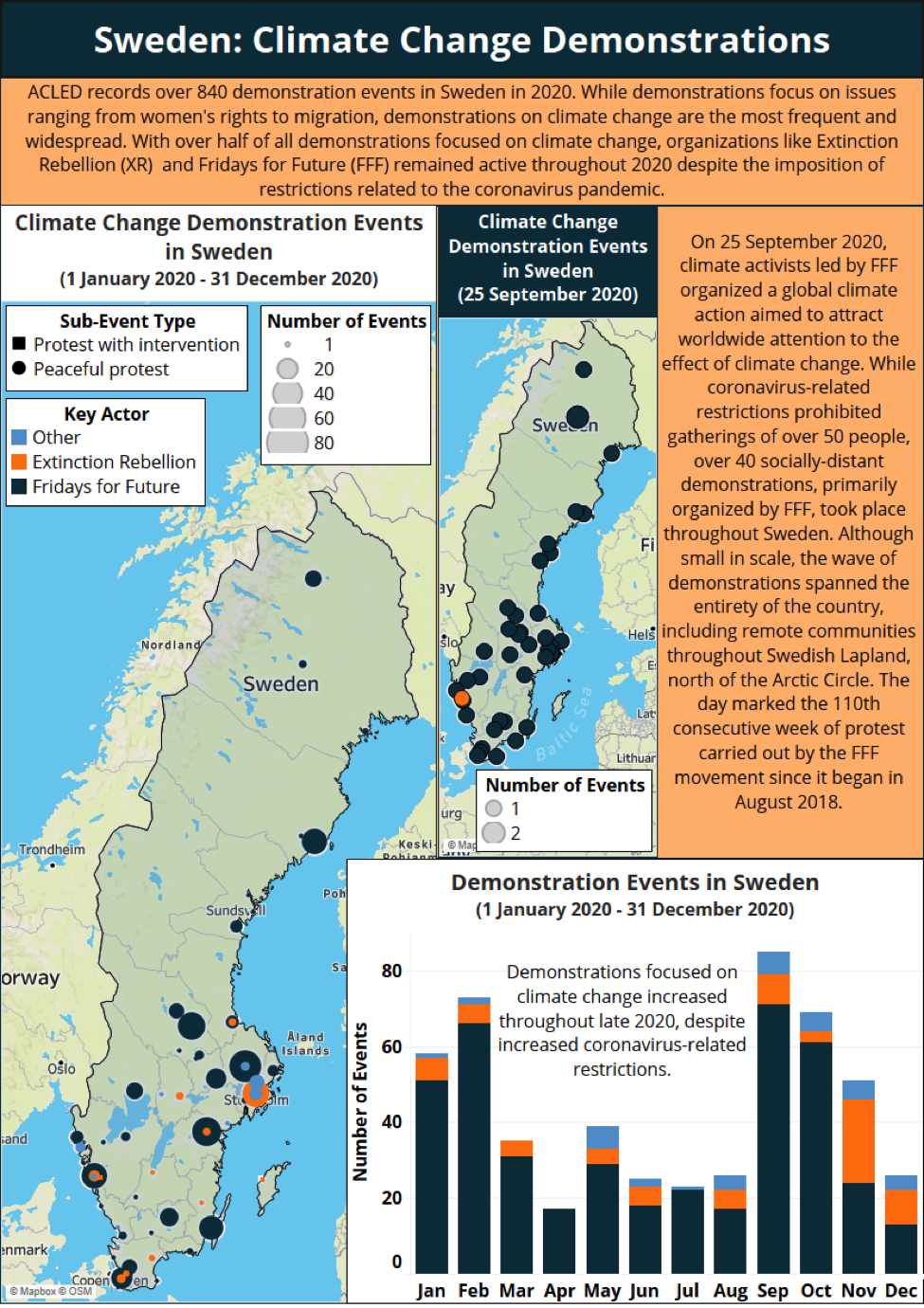

Climate change is an especially salient issue in Sweden, as illustrated by the persistence and geographic breadth of climate-related protests across the country in 2020. The youth-led Fridays for Future (FFF), as well as the more radical Extinction Rebellion (XR), have remained the two most prominent activist movements in the country. While both movements are global in reach and share many of the same goals, their tactics and activities vary considerably. While the FFF demonstrations have generally taken the form of student-led school strikes, XR demonstrations tend to employ more disruptive tactics, like road blockades and delaying flight traffic. XR activists have also increasingly flouted coronavirus-related restrictions on public gatherings, leading to several instances of police intervention. Overall, both movements have remained non-violent and have managed to promote climate change as an urgent issue in Sweden.

FFF is an international social movement of students and environmental activists that emerged in 2018. It was initiated by Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg with the aim to demand action against climate change from political and economic leaders (Atlas of the Future, 11 December 2019). Also present in Sweden, one of the most significant climate related movements is the XR. This international group was founded in 2018 in the United Kingdom to fight against climate change, biodiversity loss, and the risk of socio-ecological collapse.

While the scale of protest activity associated with these movements is global, Sweden has witnessed a considerable proportion of FFF and XR demonstrations in 2020. Demonstrations were held in more than 30 cities across the country (SVT, 25 September 2020). The largest “climate strike” was carried out on 25 September and was attended by members of many different environmental groups, though FFF took a leading role.

Many of the actions, performances, and blockades organized by XR often result in arrests, detentions, and criminal charges. On 30 June, two XR activists staged a protest performance in a Scandinavian Airlines airplane, which was set to fly from Landvetter Airport, near Gothenburg, to Stockholm to draw attention to the carbon dioxide emission issue and to demand an end to the use of airplanes. They refused to obey the flight attendants and leave the plane. Later, both activists were arrested and preliminarily charged with aviation sabotage, which is considered a serious offense and in some cases carries a prison sentence of two to 10 years (Expressen, 30 June 2020). A day earlier, around 10 XR activists attempted to halt the departure of a local flight at Angelholm airport. One protester glued herself to the plane while four others held banners on the runway, and five people protested inside the airport. This case is also being investigated as aviation sabotage, though no one was arrested at the time of the demonstration (Helsingborg Dagblad, 29 June 2020).

Worth noting is the difference in approach to compliance with COVID-19 restrictions among the different movements. FFF activists have mostly followed coronavirus-related regulations, including recommendations to wear masks and to socially distance. XR protesters, meanwhile, have often violated the restrictions, particularly mass gathering limits — which has then given authorities cause to arrest them. For example, from 27 to 28 August, around 400 XR activists (NB Nyhetbyran, 28 August 2020) blocked traffic on several major streets in Stockholm to draw attention to the climate crisis and to demand the establishment of a climate emergency in the country. Later, police personnel broke up demonstrations in various places as the number of protesters exceeded the maximum of 50 people allowed to gather under rules aimed at stopping the spread of the coronavirus (SVT, 28 August 2020).

After restrictive measures were further tightened by the government on 24 November, reducing the maximum number of people allowed to assemble from 50 to eight, XR activists continued to protest. Meanwhile, many local FFF groups switched their activities to online protests7Online protests are not coded, as they do not meet ACLED’s threshold for inclusion. or continued with small-scale physical demonstrations in compliance with COVID-19 restrictions, such as the gathering limit of eight people.

Both FFF and XR continue to be influential in making climate change a key issue in Swedish politics and society. For example, in January 2020, the municipality of Malmö adopted a “climate emergency” (Aftonbladet, 15 January 2020), having been influenced by the protests and actions of environmental groups. Given the endurance of climate protests in a year where so much energy has been directed at managing the coronavirus pandemic, it stands to reason that climate change will continue to be a defining issue in Sweden in 2021.

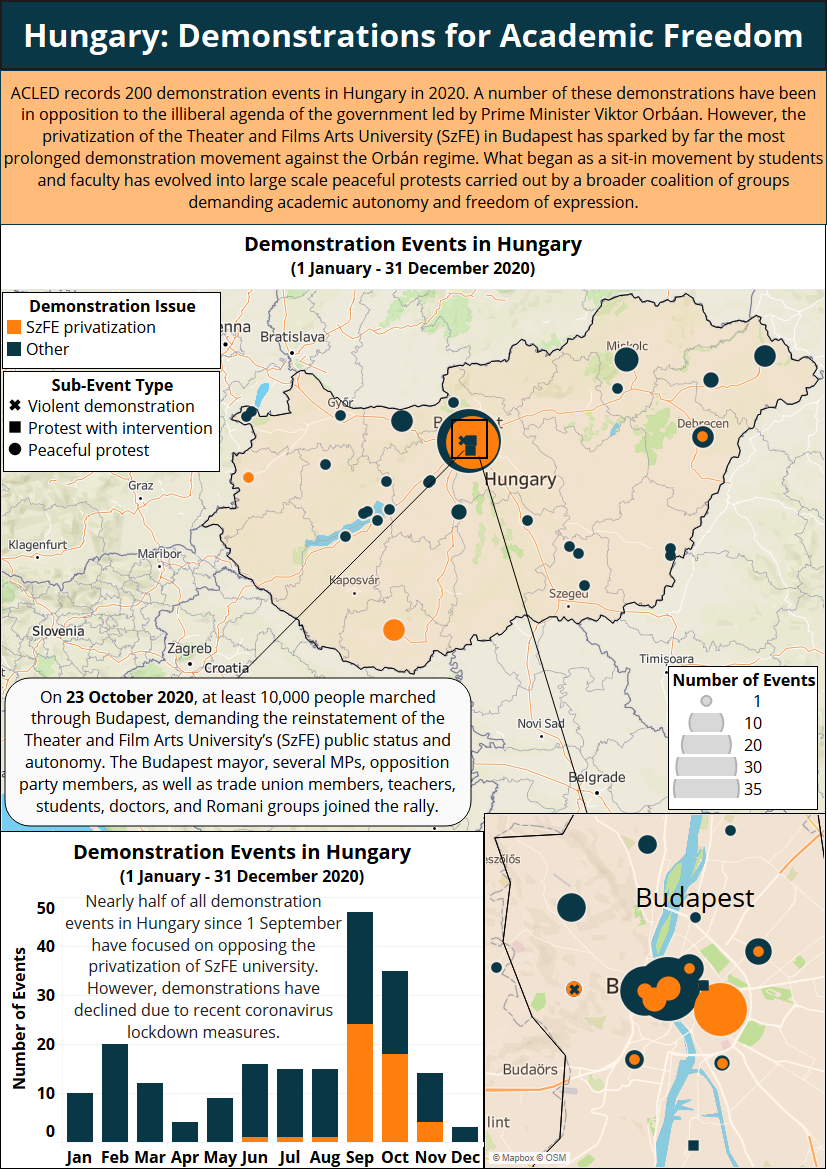

When the Theater and Film Arts University (SzFE) was forcibly privatized in 2020, it sparked the first prolonged protest movement against the Hungarian government’s attempts to control academia. The effort, led by Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and the right-wing Fidesz Party, to expand the government’s authority over the academic sphere is likely to further erode popular support for the increasingly illiberal regime. The government appears to have been caught off guard by the significant opposition mounted by the theater and film students, faculty, and staff.

Since its election in 2010, the Hungarian government led by Orbán has sought greater power over state institutions, private sector institutions, civil society, and the press. Such actions, along with the theft of public and EU funds (New York Times, 3 November 2019; Index.hu, 3 September 2019), were conducted either by changing legislation, appointing Fidesz governing party affiliates into key public positions, or by targeted takeovers through loyal businesspeople (Human Rights Watch, 7 July 2020).

A more recent instrument for such takeovers involves the privatization of public institutions. This process was used in the so-called “model change” invoked for the privatization of the Corvinus University of Budapest and five other universities in Hungary, nominally used to make the institutions more competitive (Hungary Today, 6 September 2019; Autocracy Analyst, 11 October 2020). The forceful privatization of the SzFE was an attempt by the government to impose control over a public university without consultation (Index.hu, 19 June 2020). Students and teachers of the SzFE argue that the designation of a director of the board with a controversial record in the theater (Hungarian Spectrum, 3 August 2020), the appointment of a military colonel as the university’s chancellor (InsightHungary, 1 October 2020), and the absence of faculty in the university’s board undermine the institution’s autonomy.

Hungarians tend to view the theater and film sectors as apolitical — despite these sectors regularly criticizing almost every government. Additional concerns were raised by students who feared losing scholarships and state support after the privatization. The concerned ‘university citizens’ were joined later in protests by university employees who also demanded a pay raise and a return to the university’s previous status (!!444!!!, 26 October 2020).

Students have demonstrated outside the SzFE university at least twice a week since early September. In early September, a movement similar to the American ‘Occupy’ protests formed on the premises of the campus. Students and teachers held lectures and prevented the new leadership from entering the campus. The new leadership objected to the legality of such lectures, eventually suspending the semester and threatening students and employees who did not cooperate with them (!!444!!!, 6 November 2020; InsightHungary, 15 October 2020). The biggest protest occurred on 23 October when tens of thousands of demonstrators, including members of civil society groups and opposition parties, joined SzFE students and faculty (Szabad Európa, 23 October 2020). The protest movement is supported by significant Hungarian opposition parties, such as Momentum, Democratic Coalition (DK), Politics can be Different (LMP), and Párbeszéd. However, the protesters have called on the political parties to refrain from further politicizing the issue. Hungarian actors, directors, and writers also stood guard near the university buildings.

The university ‘blockade’ continued peacefully for 70 days until early November, when it was abruptly suspended by the protesters to avoid being accused of violating the lockdown implemented amid the coronavirus pandemic (!!444!!!, 10 November 2020). The movement has since organized online,8Online protests are not coded, as they do not meet ACLED’s threshold for inclusion. as the public health situation and accompanying restrictions prohibit gatherings — though the movement’s demands remain the same.

Other controversial measures introduced by Fidesz to target academia have elicited a strong response across the European Union (EU) (Coda Story, 2020). The adoption of the ‘Central European University law’, which forced the prestigious institution to move out of the Hungarian capital, and the privatization of the Corvinus University of Budapest along with five other universities, has caused significant reactions at the EU level and outrage among the students of these universities.

Additionally, the banning of gender studies programs, the enforcement of tighter controls over research conducted at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, and the adoption of the patriotic National Basic Curriculum (NAT) triggered large street protests supported by academia, civil society, and teachers’ unions last year. However, these demonstrations did not last as long as the SzFE protests. The special status of theater and film within Hungarian culture, coupled with the realization that fewer institutions remain independent from the Fidesz government, might have galvanized a stronger push for the cause of the SzFE autonomy, despite the pandemic.

Although there is no sign that the government will withdraw its bill on the private status of the SzFE, it may suffer in the parliamentary elections scheduled for 2022 due to dissatisfaction with its response to the COVID-19 pandemic. It is hard to predict how the Orbán government will respond to the likely resumption of the protests in early spring of 2021, when the weather improves and coronavirus restrictions might be relaxed. A weaker position in the polls for Fidesz in the lead-up to elections in 2022 might translate into an unwillingness to compromise, instead pushing Orbán to adopt additional far-right policies to mobilize voters, and to limit political freedoms.

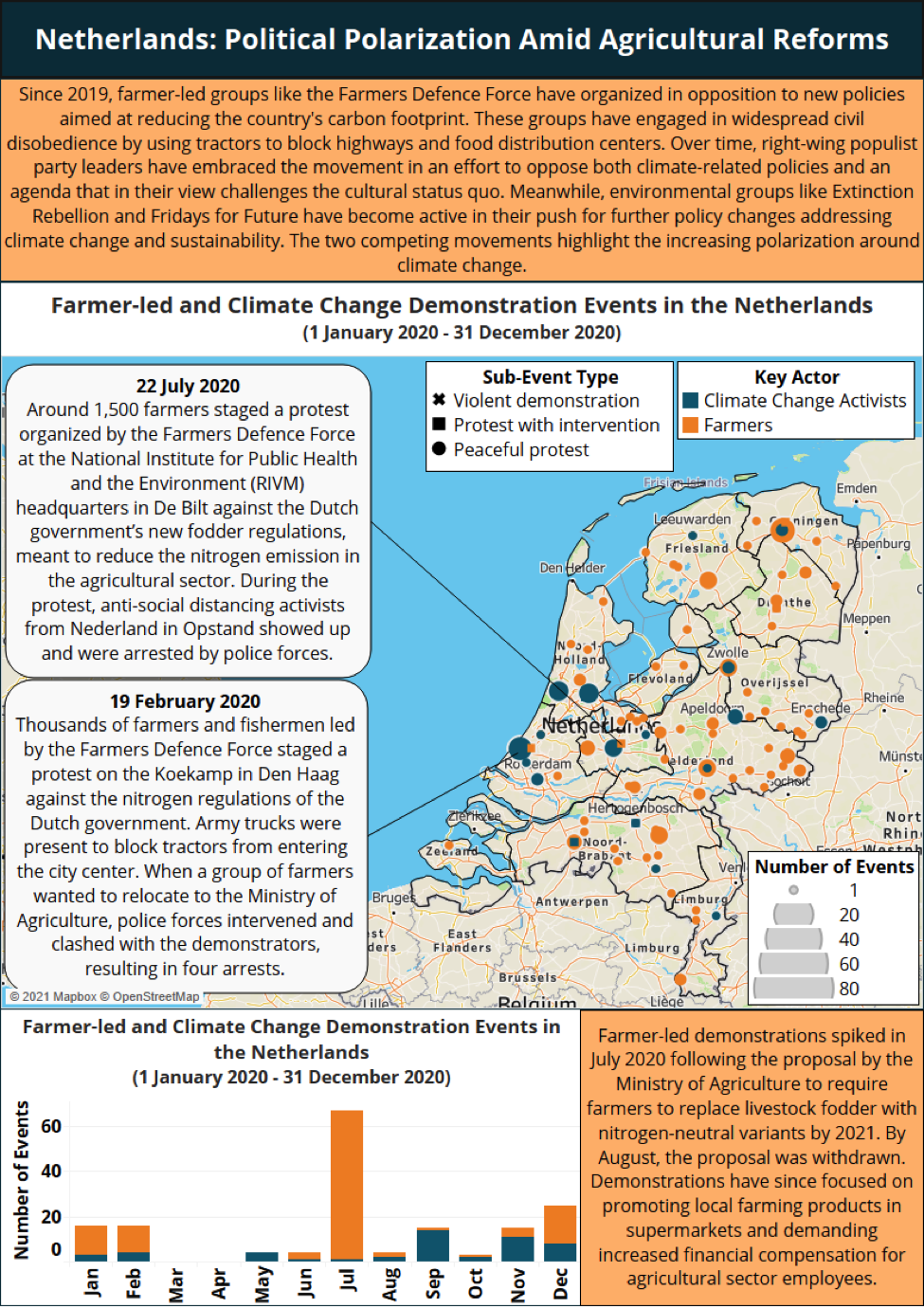

Climate change policy has become an increasingly polarized issue in the Netherlands. In an effort to reduce its carbon emission footprint, the Netherlands has introduced a series of reforms affecting the agricultural sector. Farmer-led groups like the Farmers Defence Force have organized in opposition to the new policies since 2019. Meanwhile, environmental groups like Extinction Rebellion (XR) and Fridays for Future (FFF) have become more active in their push towards further policy changes addressing climate change and sustainability, thus increasing polarization in the Netherlands around climate change policy. As a consequence, the farmer movement has become increasingly enmeshed in the broader political agenda of right-wing populist parties. In their historical struggle against the left-liberal disturbance of societal status-quo (e.g. on migration), these parties instrumentalize the farmer movement to open up a new area of contestation: climate change policy.

The current wave of organized farmer protests in the Netherlands took root after a pig stable occupation in Boxtel by around 100 activists of the animal rights action group Meat The Victims in May 2019. Farmers from the region assembled at the farm, where they nearly clashed with animal rights activists. Since then, the threat of stable occupations led to the foundation of the Farmers Defence Force, a loosely structured farmer interest group organizing farmers through WhatsApp to monitor the movements of animal rights activists and to mobilize in the event of a new occupation. However, their focus shifted to the agricultural policy of the Dutch government after a Member of Parliament from D66, a party in the ruling coalition, suggested in September 2019 that the Dutch livestock population be reduced by half in the following years (AD, 9 September 2019).

Since the Dutch government Rutte III introduced its Climate Agreement in the summer of 2019, a series of new government regulations were implemented to reduce methane and nitrogen emissions in the agricultural sector. The government sought to reduce these emissions by halting large-scale agricultural construction projects and imposing restrictions on the use of nitrogen in the agricultural sector. However, the livestock plans of D66 were not part of these changes and caused considerable contention within the Rutte III government by the Minister of Agriculture, of the ChristenUnie party, and coalition partner Christen-Democratisch Appel (CDA), which is traditionally strong among farmers (RTL, 9 September 2019).

Nevertheless, the response of the agricultural sector was firm and unexpectedly widespread. The newly founded Farmers Defence Force, outraged by the way the already struggling farming sector was expected to pay the nitrogen bill, organized individual farmers into a protest movement. In the fall of 2019, massive farmer protests took place all over the country that were unique in terms of scale and impact, with thousands of farmers blocking highways and food distribution centers with tractors and heavy machinery (Omroep Brabant, 24/12/2019). Under the guidance of the Farmers Defence Force, most agricultural interest groups were united under an umbrella organization, “Landbouw Collectief,” to put pressure on the government to withdraw its nitrogen regulations.

This trend of organized farmer protests continued into 2020, despite a period of inactivity due to the coronavirus lockdown in the spring and again at the end of 2020. A total of 121 events were reported across the country, with considerable peaks in the beginning of February, July, and December 2020. Continuing the trend of 2019 (Omroep Brabant, 24/12/2019), protest activity was mainly directed against the nitrogen policy of the Dutch government. Protests in early February 2020 were used as a means to put pressure on negotiations between farmers and the Ministry of Agriculture. While the surge of farmer protests in the beginning of July 2020 was a direct consequence of a new fodder regulation aimed at reducing nitrogen emissions by compelling farmers to switch to nitrogen-neutral fodder varieties. The reaction among farmers in terms of scale and geographic spread, and the withdrawal of the rule in August 2020, suggests that agricultural policy will continue to be an important source of protest activity in the Netherlands in the future.

2020 also saw some changes in farmer protest activity. Increasingly, food distribution centers of major supermarket chains, such as Albert Heijn and Jumbo, were the target of protest blockages. This indicated that the farmer movement reshifted its main focus from the contestation of agricultural government policy to advancing an agenda of farmer re-evaluation in a much broader sense. The farmer protests of December 2020 were aimed at forcing supermarket companies to contribute to the Farmer Friendly cooperation. The cooperation was initiated by the Farmers Defence Force to establish a supply chain from local farmers to supermarkets. Notably, these protests took place despite a call from the Farmers Defence Force to renounce the blocking of distribution centers so that they could facilitate negotiations with the supermarkets. This shows that the farmer movement is still a very loose structure of individual farmers without a clear common agenda.

Given the conflicting views on agricultural policy within the Rutte III government, the government’s response has been ambivalent towards the farmer protests. While 2020 started off with a rapprochement towards the sector, the unilateral introduction of the fodder regulations in July 2020 and its withdrawal one month later were signs of a government in distress (NRC, 19 August 2020; Trouw, 13 October 2020). On the other hand, the government response towards the farmers’ disruptive protest techniques has been firmer in 2020. They deployed the army in Den Haag in February to prevent the farmers from driving into the city center, imposed provincial bans on the use of tractors during the protests in July, and increased police presence during demonstrations, arresting protesting farmers throughout the course of the year. While this radicalized some farmers in their stance towards the government, resulting in the threatening of key politicians and government officials, it also alienated many farmers from a hardline attitude in the face of waning popular support for the farmer cause. This eventually caused the break up of the Landbouw Collectief (BNR, 6 mei 2020).

The political impact of the farmer protests in the Netherlands should not be underestimated. It proves rising polarization around climate change policy in a time when environmentalist groups like XR and FFF are increasingly pushing for further reforms. Giving voice to underground dissatisfaction with the way climate change policies are implemented, the farmer grievances have been increasingly co-opted by right-wing populist forces. Likewise, the hardline farmer discourse has evolved towards a broader critique of government policies deemed as leftist. The presence of action groups such as “Nederland In Opstand” and “Steungroep Boeren & Burgers” — and the appearance of the controversial traditional blackface figure Zwarte Piet, or Black Pete, during some farmer protests (Hart van Nederland, 5 July 2020) — already point in that direction. The farmer protests have also provided ammunition to populist right-wing parties such as Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV) and Forum voor Democratie (FvD), which have used the issue to contest leftist agendas and accuse the incumbent Dutch government of disrupting the societal status quo (NRC, 10 July 2020; RTL, 18 October 2019; Trouw, 7 February 2020). It should be noted that this affiliation is not explicitly employed by the farmer movement, which is still a very diverse amalgam. Yet, the politicization of the farmer movement cannot but have a profound effect on deepening polarization in the Netherlands between the advocates of an ambitious climate policy and its discontents.

© 2021 Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). All rights reserved.