In ACLED’s special report on 10 conflicts to worry about at the start of 2021, we identified a range of flashpoints and emerging crises where violent political disorder was likely to evolve or worsen over the course of the year: Ethiopia, India & Pakistan, Myanmar, Haiti, Belarus, Colombia, Armenia & Azerbaijan, Yemen, Mozambique, and the Sahel.1This list is non-exhaustive, and rather intends to highlight 10 cases where new directions and patterns of violence are becoming clear, where there have been major shifts in conflict dynamics, and where there is an especially significant risk of conflict diffusion. Our mid-year update revisits these 10 cases, tracking key developments in political violence and protest activity during the first half of 2021 and analyzing trends to watch in the coming months.

Access ACLED data directly through the export tool, and find more information about ACLED methodology in our Resource Library.

Mid-Year Update: 10 Conflicts to Worry About in 2021

Read the full report or click through the drop-down menu below to jump to specific cases.

The summer of 2021 has been the most destabilizing time yet in Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s tenure. While the general election resulted in the Prosperity Party’s (PP) overwhelming victory, violence from multiple active insurgencies in Ethiopia has overwhelmed federal resources, with the threat posed by the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) most apparent in recent summer months.

Despite these threats, violence was minimal on the day of Ethiopia’s long-anticipated election on 21 June 2021, with few security incidents reported. Although logistical issues and scattered violence took place during voting, election day was generally peaceful and widespread violence did not occur (see EPO Weekly: 19-25 June 2021 for more detailed analysis). Yet difficulties remain: voting did not take place in many locations of the country due to ongoing clashes; popular opposition parties boycotted the election after top leaders were arrested; and the government lost control of the Tigray regional capital, Mekele, following a heavy offensive by the TPLF. Even with a sweeping electoral win, solving Ethiopia’s complex political puzzle will be a challenge for the prime minister and the ruling PP.

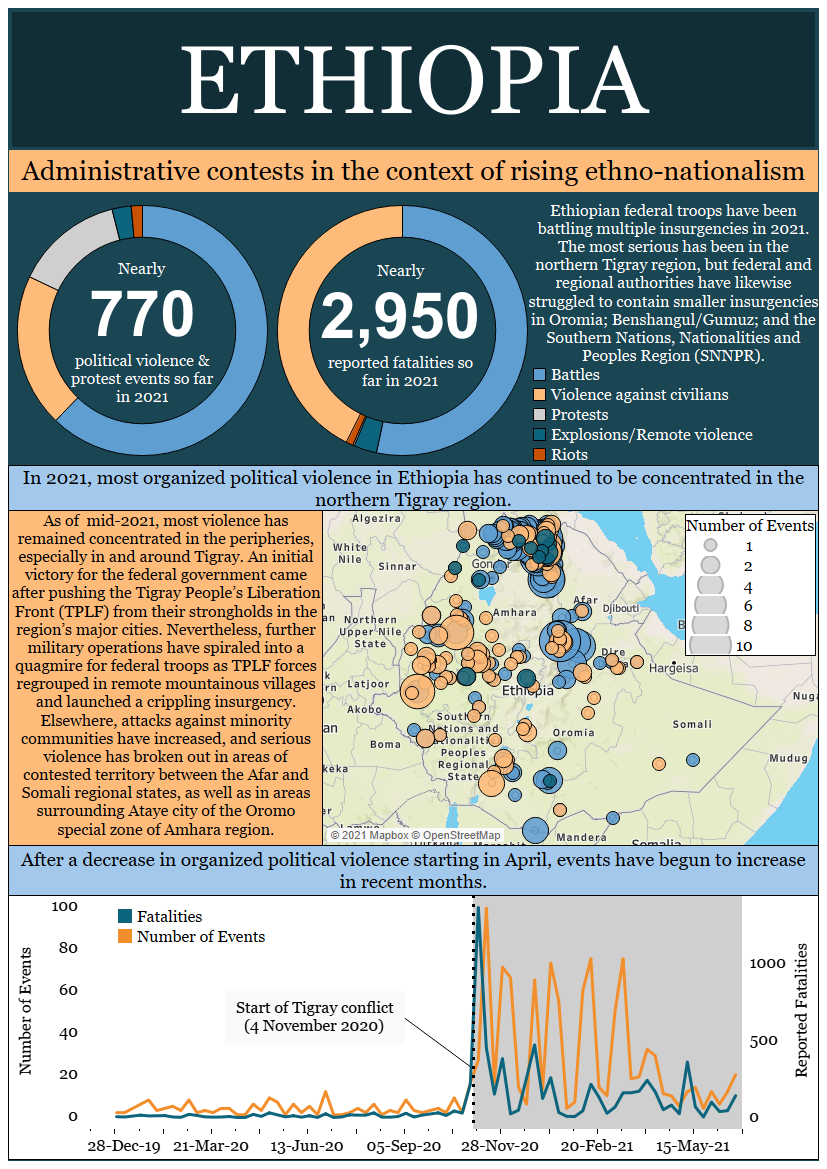

Ethiopian federal troops have been battling multiple insurgencies throughout the country in 2021, the most serious being in the northern Tigray region. An initial victory for the federal government came after pushing the TPLF from their strongholds in the region’s major cities in late 2020. Nevertheless, further military operations have spiraled into a quagmire for federal troops as TPLF forces regrouped in remote mountainous villages and launched a crippling insurgency. On the ground, Ethiopian army troops have faced a guerrilla force that assassinated interim authorities and attacked military convoys, complicating efforts by the central government to govern the region (VOA Amharic, 1 June 2021; Office of the Prime Minister – Ethiopia, 3 June 2021). As federal soldiers struggled to maintain territorial control, Ethiopia’s top officials have faced heavy diplomatic pressure — including sanctions — over the involvement of Eritrean troops, civilian targeting, and sexual violence (New York Times, 24 May 2021; Reuters, 15 April 2021; EBC, 3 July 2021). Frustrated and facing a humanitarian and military disaster, the government decided to withdraw in the last days of June 2021.

Federal and regional authorities have likewise struggled to contain smaller insurgencies in Oromia; Benshangul/Gumuz; and the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region (SNNPR). Attacks against civilian minority communities have increased across the country. Serious violence has also broken out in areas of contested territory between the Afar and Somali regional states, as well as in areas surrounding Ataye city of the Oromo special zone of Amhara region. Hundreds of people have been killed and thousands displaced in conflicts largely overshadowed by the highly publicized Tigray war.

As the finalized electoral results emerge, Ethiopia will enter a new political phase as elected officials debate constitutional issues built into the country’s ethno-federal system of governance. Territorial questions, secession, and identity politics will be central to these debates — along with the management of security and international relations regarding the war in Tigray.

The power that central authorities have to address these issues, however, lies with whatever capacity remains in the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF). The extent of damage inflicted on the Ethiopian and Eritrean armies in Tigray is difficult to estimate, as troops were evacuated quickly in the face of the TPLF advance into Mekele in the last days of June. By the government’s admission, however, conditions in Tigray had become “unbearable” for Ethiopian soldiers prior to withdrawal (New York Times, 30 June 2021). As many as 7,000 troops of the Ethiopian military were reported by international journalists to have been taken captive (New York Times, 2 July 2021), though government sources have insisted that the number of ENDF members held by the TPLF is exaggerated (Ethiopian Broadcasting Corporation, 3 July 2021). If it is the case that federal forces have been incapacitated or the ranks cannot be filled, military power will devolve to ethnically exclusive forces loyal to the regional governments, like the Amhara special forces controlling Western Tigray zone. There is some evidence that this has already occurred, given the prominent role Afar and Amhara militias have played in holding off TPLF advances in July 2021.

As noted in the original installment of this report series at the beginning of the year, authority shifts involving regional officials in Ethiopia have been a key driver of conflict and remain difficult issues to resolve. The administration of Western Tigray zone has long been contested and was inhabited by both ethnic Tigray and Amhara prior to the start of the conflict in November 2020. Both TPLF and the Amhara regional forces have been implicated in massacres of civilians during the conflict, including at Mai Cadera where an investigation found that at least 600 ethnic Amhara were killed (Ethiopian Human Rights Commission, 24 November 2020). Forces from the Amhara region have also been accused of forcibly removing ethnic Tigrayans from the zone — an act that American authorities claim amounts to ethnic cleansing (AP, 7 April 2021). The TPLF has insisted on the withdrawal of all Amhara forces from Tigray regional state boundaries and a return to the status quo — a condition that the Amhara regional state is unlikely to accept (Getachew K Reda, 29 July 2021; Addis Standard, 14 July 2021).

In the state’s largest region of Oromia, elected regional authorities are unquestionably loyal to the PP, but the federal government may face legitimacy issues especially around proposed changes to the constitution which may limit the demographic power of the Oromo group. Oromo parties other than the Oromo Prosperity Party (O-PP) — including Oromo Federal Congress (OFC) and the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) — denounced the election, calling instead for a national dialogue, the establishment of a transitional government, and for new elections to be held within a year (OFC Statement, 23 June 2021; OLF, 1 July 2021; Addis Standard, 26 June 2021). They will also be opposed to any proposed changes to the federal constitution that reinforce ethnic-based territorial authority.

Violence levels in Ethiopia are likely to remain high during the remainder of 2021. The federal government will continue to face multiple ongoing conflicts, as well as another round of voting in regions that did not participate in the last round of elections due to electoral disputes and ongoing violence. The country’s Somali region and select zones of Benshangul/Gumuz region are scheduled to vote in September of this year. Voting will not take place in the Tigray region due to continued instability and a loss of control by the federal government (France 24, 21 June 2021).

Conducting and winning a national election was an enormous task completed by Prime Minister Abiy in June. However, with opposition figures jailed and large swaths of the country in turmoil, the victory may be considered somewhat hollow. What remains to be seen is if the electoral win will provide Abiy the strength to overcome the forces rising against him from across the country.

Further reading:

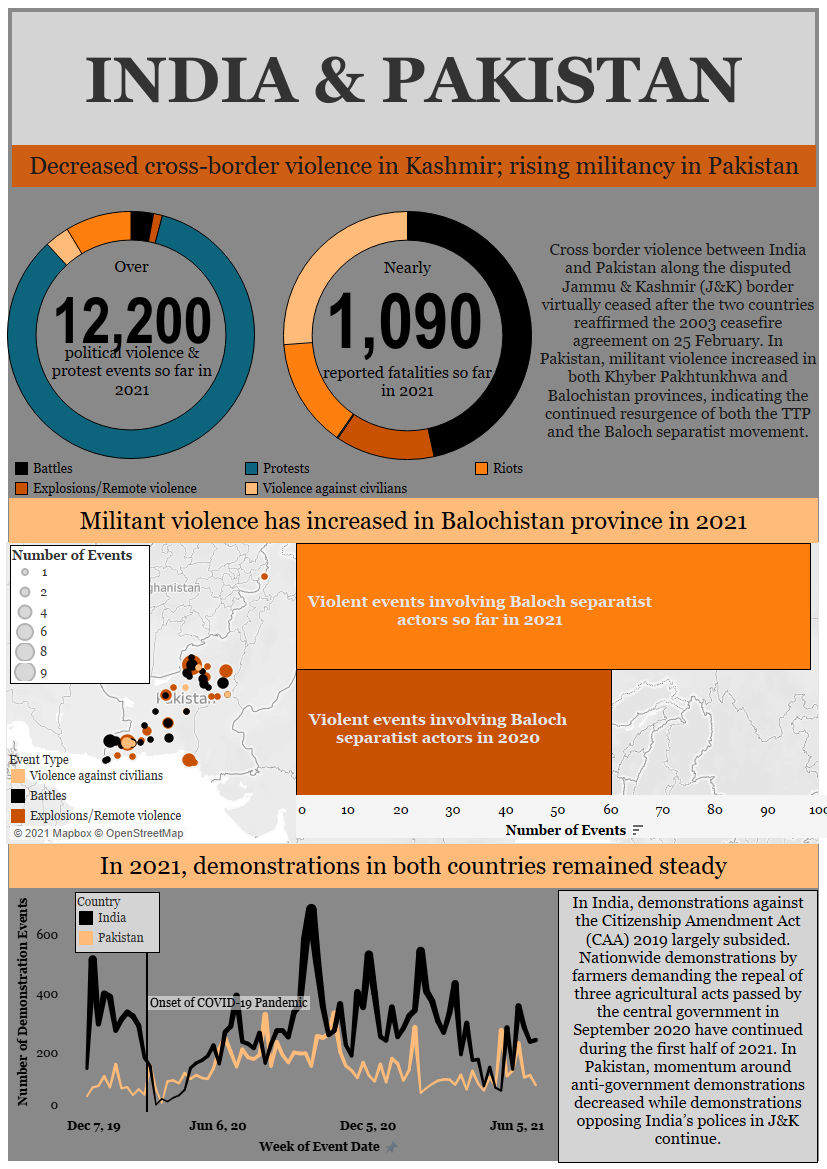

A spike in cross-border fighting made 2020 the most violent year for conflict between India and Pakistan since the beginning of ACLED coverage in 2016. Yet, contrary to expectations at the beginning of 2021, cross-border violence virtually ceased after the two countries reaffirmed the 2003 ceasefire agreement on 25 February 2021 (Al Jazeera, 25 February 2021). The reaffirmation of the ceasefire agreement followed a decline in cross-border tensions early in the new year. This downward trend emerged from back-channel negotiations between India and Pakistan that were reportedly initiated by Pakistan’s army chief in January 2021 (Financial Times, 5 April 2021, The Diplomat, 19 March 2021). Both India and Pakistan have largely adhered to the ceasefire, apart from two incidents in May and June.

Although the ceasefire has held, the situation remains tense. On 27 June, suspected Lashkar-e-Taiba militants launched a drone attack, the first of its kind, on a military facility in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) (The Hindu, 2 July 2021). Two bombs were dropped inside an Indian Air Force station by drones in Jammu district, injuring two officers. Indian security forces accuse Pakistani security services of providing support to militants to conduct the attack (The Hindu, 11July 2021), though Pakistan denies the accusations (The International News, 30 June 2021). In the past, major attacks by militant groups on both Indian military and civilian targets in J&K have led to a break in negotiations and an escalation of violence (for more, see this ACLED analysis piece). While this fragile peace continues to hold along the India-Pakistan border, disorder persists in other parts of both countries.

In J&K’s neighboring region of Ladakh, a disengagement agreement in February led to withdrawal of both Chinese and Indian forces from the north and south banks of Pangong Tso Lake. In May and June last year, clashes along the Line of Actual Control2A border alignment between China and India that separates Indian-controlled territory from Chinese-controlled territory but has not yet been delineated or demarcated. led to the deaths of 20 Indian and at least four Chinese soldiers (The Hindu, 13 June 2020; Reuters, 18 February 2021). Following the 2020 clashes, troops from both sides positioned themselves on the north and south banks of the lake (BBC, 21 February 2021). Tensions remain high in the region as phased disengagement and the withdrawal of troops at other contentious areas in eastern Ladakh have yet to take place (The Print, 22 April 2021). In addition, both India and China have bolstered the number of military personnel and infrastructure along the disputed border in recent months (The Wall Street Journal, 2 July 2021).

Elsewhere in India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his government held an all-party meeting with political leaders from J&K in June. This is a first since August 2019, when J&K’s special status was revoked and the region was bifurcated into two union territories. The meeting was attended by 14 J&K leaders, including four former chief ministers. During the meeting, the government outlined its intentions to soon complete redrawing the boundaries of assembly seats and to hold assembly elections quickly thereafter. While the home minister indicated that the statehood of J&K — a key demand for Kashmiri political leaders — would be restored in “due course,” no timeline was agreed to (The Wire, 25 June 2021). The restoration of statehood would ensure that people in J&K would have the right to elect their own state government. Currently, J&K is a federal territory governed by the central government of India through an appointed lieutenant governor.

Demonstrations against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) 2019 have largely subsided since mid-February, with the exception of protests in the northeast state of Assam, in March. The All Assam Students’ Union launched statewide demonstrations against the CAA just before the first phase of Assam’s state assembly elections; since their completion in early April, anti-CAA demonstrations have not been reported in Assam. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which is the main proponent of the CAA, secured a majority in the elections while also inducting several prominent anti-CAA leaders into the party (The Quint, 26 March 2021; Scroll, 2 May 2021). However, other anti-CAA movement leaders have vowed to continue protesting and, once implementation begins, demonstrations and violence are likely to renew and escalate (The Economic Times, 2 July 2021). The Indian Ministry of Home Affairs missed another deadline on 9 July to finalize the rules for the CAA, and the deadline has now been extended by another three months (The Economic Times, 3 June 2021).

Meanwhile, nationwide farmer demonstrations demanding the repeal of three agricultural acts passed by the central government in September 2020 have continued during the first half of 2021. Due to the new legislation, farmers fear losing market protections, including a minimum guaranteed price for their produce (BBC News, 27 November 2020). Despite 11 rounds of talks between farmers and the government, no agreement has yet been reached. The government has hinted that talks with the farmers could resume, but has ruled out a complete repeal of the laws — a key demand of the farmer unions (Outlook, 18 June 2021; Foreign Policy, 13 January 2021). The demonstrations are set to continue with the farmer unions’ planned daily sit-in protest outside the parliament in the capital, Delhi, throughout the monsoon season.

In Pakistan, militant violence increased in both Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan provinces, indicating the continued resurgence of both the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and the Baloch separatist movement. Already this year, the TTP has claimed large-scale attacks in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa as well as in the heart of the provincial capital of Balochistan. During the first half of 2021, violence involving the TTP in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has nearly equaled levels recorded during the entirety of last year. Similarly, after a long period of decline, violence involving Baloch separatist groups has continued to rise in 2021. Baloch separatist groups have increasingly targeted the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which aims to build infrastructure and expand trade links across Eurasia, and Chinese interests in the province (Gandhara, 8 June 2021). The separatists oppose Chinese infrastructure development and investment and consider such projects to be an exploitation of local labor and natural resources (Deutsche Welle, 14 July 2021).

In other developments, the Pakistan Democratic Movement, an alliance of opposition parties that aimed to oust Prime Minister Imran Khan, lost the momentum it had gained during anti-government demonstrations at the end of last year. In April, two major opposition parties quit the alliance after disagreements over the nomination for the leader of the opposition in the senate (Dawn, 13 April 2021). The anti-government national march, planned to be launched in March, was also postponed. Currently, efforts are being made to revive the alliance (Dawn, 25 May 2021). While anti-government demonstrations decreased, overall demonstration levels in Pakistan have remained steady. Demonstrations opposing India’s policy in J&K have continued, and large nationwide demonstrations have been held by Islamist parties.

Further reading:

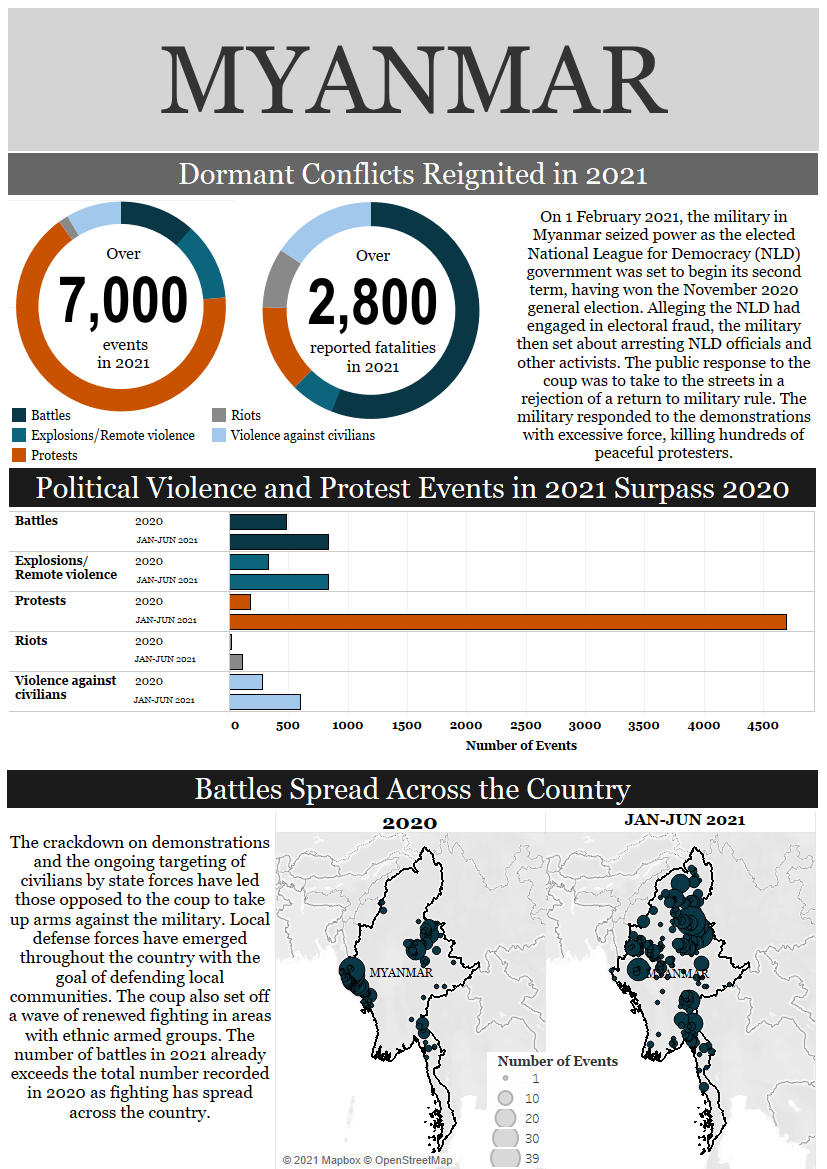

On 1 February 2021, the military in Myanmar seized power as the elected National League for Democracy (NLD) government was set to begin its second term, having won the November 2020 general election. Alleging the NLD had engaged in electoral fraud, the military set about arresting NLD officials and other activists. The public response to the coup was to take to the streets in a rejection of a return to military rule. The military responded to the demonstrations with excessive force, killing hundreds of peaceful protesters. As military violence throughout the country increased, armed local defense forces emerged to protect communities. The coup has also set off a wave of renewed fighting in areas with ethnic armed groups. ACLED records an increase in all political violence and protest event types tracked in Myanmar during the first six months of 2021, surpassing the total event counts for all of 2020.

Demonstrations against the coup have been widespread and are ongoing. Throughout the month of February, demonstrators marched daily in cities, towns, and villages across the country. As the military and police began to crack down on demonstrations, using excessive force and killing peaceful protesters, demonstrators adapted by staging flash mob-style rallies. While these demonstrations have declined overall since February, dozens are still recorded each week.

The crackdown on demonstrations and the ongoing targeting of civilians by state forces have prompted many opposed to the coup to take up arms against the military (for more, see ACLED’s recent report: Myanmar’s Spring Revolution). On 5 May, the National Unity Government (NUG), composed of elected lawmakers overthrown by the military, announced the formation of a ‘People’s Defense Force’ (PDF) in anticipation of raising a new federal army (Irrawaddy, 5 May 2021). Many newly formed local defense forces have adopted the PDF name and indicated loyalty to the NUG, while other local defense forces have remained independent of the NUG. While much of the fighting between state forces and local defense groups has taken place in rural areas of Chin state and Sagaing region, as well as Kayah state, clashes have been recorded in urban areas as well, including in the second city of Mandalay.

There are varied responses from existing ethnic armed groups to the coup, with some supporting the anti-coup movement and others not. The United League of Arakan/Arakan Army (ULA/AA) — an ethnic Rakhine armed group that had battled the military for the past two years — has not clashed with the military since shortly after the November 2020 elections. They have resisted outreach from the NUG and have closer relations with the military since they were removed from its list of “terrorist” organizations in March (Irrawaddy, 17 June 2021). While Rakhine state remains free of clashes as the unilateral ceasefires noted at the beginning of the year appear to have held for now, no stable political solution to the conflict has been reached.

Meanwhile, both the Kachin Independence Organization/Kachin Independence Army (KIO/KIA) and the Karen National Union/Karen National Liberation Army (KNU/KNLA) have largely supported anti-coup actions, while still resisting calls to join the federal army envisioned by the NUG. Fighting between the military and KIO/KIA has restarted in Kachin state, which had seen infrequent clashes since mid-2018. Battles between the military and KNU/KNLA in Kayin state have also sharply increased alongside military airstrikes in the region. As ACLED noted at the beginning of the year, clashes between the KNU/KNLA had already begun to increase prior to the coup amid a breakdown in monitoring mechanisms put in place under previous ceasefire agreements.

In Shan state, clashes between ethnic armed groups themselves have caused displacement. The Restoration Council of Shan State/Shan State Army-South (RCSS/SSA-S) and the Shan State Progress Party/Shan State Army-North (SSPP/SSA-N), both ethnic Shan armed groups, have clashed. Fighting has also been reported between the RCSS/SSA-S and the Palaung State Liberation Front/Ta’ang National Liberation Army (PSLF/TNLA), an ethnic Palaung armed group. Clashes between these ethnic armed groups had declined in 2020 but, as ACLED observed earlier in the year, appear to have reignited over ongoing territorial disputes. The conflict between rival ethnic Shan armed groups has prevented a united Shan response to the military coup.

Amid a third wave of the coronavirus pandemic, political violence and protests are likely to continue. The military’s deliberate targeting of health workers has undermined efforts to control the spread of the virus, and deaths from COVID-19 have begun to increase significantly amid oxygen shortages (AP, 6 July 2021). The impact of the coup on many sectors of Myanmar society can be seen in the military’s response to the worsening pandemic. Resistance to the junta — both armed and unarmed — will persist, as much of the population remains firmly opposed to a return to military dictatorship.

Further reading:

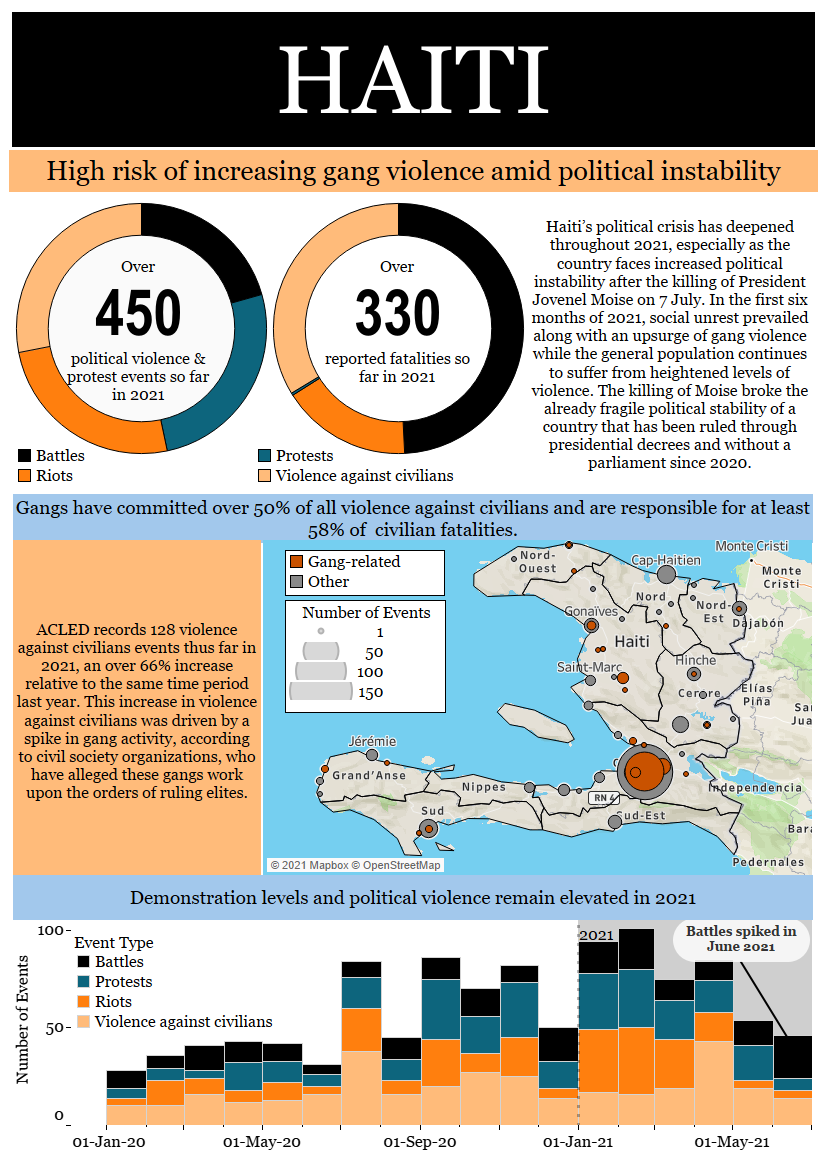

The political crisis in Haiti deepened during the first half of 2021, and the country now faces increased instability following the killing of President Jovenel Moise on 7 July. Both social unrest and gang violence intensified throughout the first six months of the year.

In early 2021, disagreements over the constitutional end of President Moise’s mandate prompted demonstrations led by the political opposition. These demonstrations occurred throughout January and February, accusing Moise of illegally exceeding his presidential term limit. Moise’s term ended on 7 February 2021, marking five years from the end of the previous term of former President Michel Martelly (BBC, 15 February 2021). Moise refused to stand down, however, claiming that his mandate extended to 2022 (Europa Press, 16 January 2021). In doing so, he cited a year-long delay to the final round of the presidential election, which prevented him from taking office until February 2017.

A proposed referendum by Moise to overhaul the existing constitution further sparked demonstrations. The proposal included a raft of changes, such as a transition from a bicameral to a unicameral legislature and reforms on the current limit of a single five-year presidential term to allow presidents to serve two consecutive terms (ConstitutionNet, 3 March 2021). The project has been rejected by the opposition, who note that the current constitution strictly prohibits holding referenda to modify it (Le Monde, 29 June 2021). Some critics also view the reform as an authoritarian move to reinforce presidential powers (AP, 3 February 2021).

Almost half of the anti-government demonstrations that took place during the first half of 2021 have been violent and/or destructive, with demonstrators regularly erecting flaming barricades and clashing with law enforcement. On some occasions, police have used live ammunition to disperse demonstrators, including peaceful protesters. Thus far in 2021, ACLED records five cases of excessive force against peaceful protesters — similar to rates seen during the entirety of 2020. Police have also targeted journalists covering demonstrations, with at least six such physical attacks reported so far this year.

Additionally, attacks targeting civilians have increased in 2021, in line with ACLED’s assessment at the beginning of the year. So far in 2021, ACLED records over 120 violence against civilians events, marking a 66% increase compared to the same time period last year. Civil society organizations have attributed responsibility for most of this violence to gangs, which allegedly work upon orders of ruling elites to fight for control of new voting constituencies (IHRC and OHCCH, April 2021). Gangs also work to silence opposition in neighborhoods of Port-au-Prince with strong anti-government sentiments, leading to violent incursions like that in the Bel-Air neighborhood, where at least 13 people were killed and others displaced during the spring between 31 March and 1 April (Miami Herald, 2 April 2021).

Disputes over the control of neighborhoods in Port-au-Prince have increased: since May, gang warfare intensified in the capital following battles for the control of specific neighborhoods and the revival of old rivalries between gangs affiliated with the G-9 alliance. The G-9 is a coalition of several gangs formed in June 2020 under the leadership of former police officer Jimmy Cherizier, and is known for having links with Moise’s government (Miami Herald, 26 June 2021). Cracks in the G-9 alliance were made evident by clashes between the Ti Bwa gang and the Ti Lapli gang; while both are members of the G-9 coalition, they were rivals prior to the formation of the G-9 alliance (Fondasion Je Klere, 22 June 2020).

As part of gang offensives to expand control over neighborhoods of the capital, they have raided police stations, stealing weapons and killing police officers (Reuters, 7 June 2021). In June, fighting between gangs and police officers reached its highest level yet. According to local organizations, gangs currently outgun the police forces, which are poorly equipped and have been directed to respond to the political interests of the ruling elite (RNDDH, 11 June 2021; Reuters, 15 March 2021).The recent clashes have raised questions about a potential breakdown of alleged ties between Moise’s government and the G-9 gang coalition (The Nation, 22 March 2021). Weeks before the president’s killing, the leader of the G-9 called for a fight against the private sector and the government, which he blamed for the country’s current crisis, and even called Moise’s constitutional referendum illegal (Alterpresse, 1 July 2021).

Escalating insecurity culminated on 7 July with the killing of President Moise by alleged mercenaries from Colombia and the United States who broke into his house in Port-au-Prince. At time of writing, three of these mercenaries have been killed and 21 others have been arrested (Al Jazeera, 12 July 2021). Police have also arrested a Haitian doctor, Emmanuel Sannon, who allegedly plotted the attack with the intention of seizing the presidency (DW, 12 July 2021). Investigations into the attack are ongoing amid tensions related to the political transition to establish a new government. The involvement of Haitian gangs remains plausible, although shortly after the attack, the leader of the G-9 alliance called for protests against Moise’s assassination, denouncing the supposed involvement of police and opposition politicians in the plot (Euronews, 10 July 2021). Others claim that the president has been increasingly unpopular among his rivals and the country’s oligarchs for trying to reform the constitution and to clean the government of corrupt contracts (Reuters, 11 July 2021).

In the immediate aftermath of the assassination, controversy arose around the future leadership of the country. On 20 July, Ariel Henry was sworn in as the new prime minister after having been chosen by President Moise for the role days before his assassination (France 24, 21 July 2021). The designation of Henry comes during political tensions between him and Claude Joseph, the acting interim prime minister at the moment of Moise’s assassination. Joseph had been designated as interim prime minister in April 2021, following the resignation of Joseph Jouthe amid criticism over his lack of action to curb gang violence in the country (La Presse, 14 April 2021). Members of the political opposition claim that Joseph agreed to step down from the position after pressure exerted by the United States, the United Nations, and other countries, demanding Henry form an inclusive government to hold general elections (The New York Times, 19 July 2021).

The fragile political agreements to fill the power vacuum amid increasing gang violence in the country open the door to future violent struggles between contenders for the presidency (RF, 20 July 2021). Past governments have relied on their alliances with gangs to keep control of social sectors and to advance their political interests (The Economist, 7 July 2021). The instrumentalization or direct participation of gangs in the power struggle could lead to further violence. Potentially, the cohesion of gangs under the G-9 flagship could further break down should different groups decide to side with different politicians, leading to even more intense gang warfare and violence against civilians across key neighborhoods of Port-au-Prince.

Further reading:

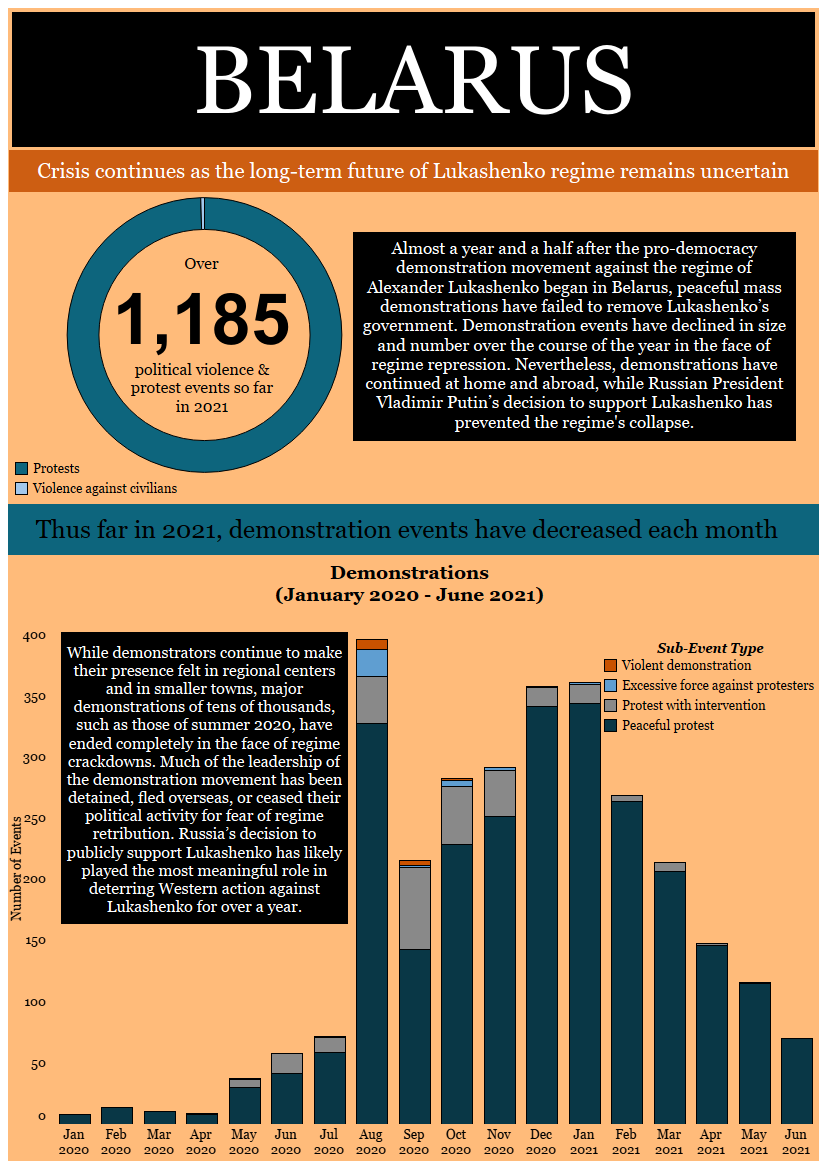

Almost a year and a half after the pro-democracy protest movement began in Belarus, peaceful mass demonstrations have failed to remove Alexander Lukashenko or break his regime. Demonstrations have declined over the course of 2021, despite the fact that the government has made no meaningful concessions. Instead, the Lukashenko regime has relied on repressive tactics, including torturing detained demonstrators and opposition figures (Amnesty International, 2021; HRW, 2021). However, despite the crackdown, demonstrations across Belarus — and by Belarusians outside the country — have continued as the international community begins to take new, yet delayed, action against the regime.

The political crisis began in May 2020 in the lead up to elections held on 9 August 2020, as Belarusians across the country demonstrated in support of the opposition, led by Svetlana Tikhanovskaya. Despite a widely discredited vote and an increasingly large and vocal opposition movement, Lukashenko claimed to have won a massive victory. This announcement provoked the public to take to the streets against the regime, with demonstrators decrying the openly authoritarian and fraudulent actions of the government. Demonstrations took place in all major cities and in many towns across the country, as the government struggled to address the crisis. In some cases, state security forces have suppressed demonstrators by arresting and torturing opposition leaders and demonstration coordinators, as well as individuals identified at demonstrations. At the same time, Lukashenko turned for support to Russian President Vladimir Putin and Russian security agencies (The Moscow Times, 3 June 2021).

Putin’s decision to support Lukashenko relatively early in the crisis saved the Belarusian regime from collapse. Russia has backed Lukashenko in a number of ways, including through economic aid, support in shaping anti-democracy information operations in Belarusian media, and increased cooperation between Belarusian and Russian security services to confront joint threats (The Moscow Times, 1 September 2020; RFE/RL, 18 December 2020). However, Russia’s decision to take a firm public stance in support of the Belarusian regime has likely played the most meaningful role in deterring Western action against Lukashenko for over a year. While Russia’s long-term agenda remains unclear, it has so far shown no sign of moving to abandon Lukashenko.

The protest movement in Belarus seems to be, at least in the short-term, losing momentum. While demonstrators continue to make their presence felt in regional centers and smaller towns, major demonstrations of tens of thousands, such as those of summer 2020, have ended completely (The Guardian, 16 August 2020). The regime’s crackdown on the opposition, combined with protest fatigue, has likely played an important role in this weakened momentum. Much of the protest movement’s leadership has been detained, pushed out of the country, or forced to cease their political activity for fear of regime reprisal. Nevertheless, demonstrations continue in areas where regime security forces are less vigilant, often with displays of the white-red-white flag, the symbol of the opposition. Meanwhile, the leadership of the Belarusian opposition, headed by Tikhanovskaya, continues to organize support outside of the country.

Recently, the European Union, the United States, and other countries have attempted to increase political and economic pressure on Lukashenko’s regime through sanctions on regime-linked entities (European Council, 24 June 2021). However, these sanctions have come well after the zenith of demonstration activity in the summer and fall of 2020, and will likely have minimal impact on regime behavior. Indeed, the regime has recently taken risky actions with international implications in pursuit of opposition figures, underlining its ability to act with near impunity when dealing with perceived opponents within its borders. The use of military assets to ground an airliner flying from Athens, Greece to arrest a prominent opposition journalist is just one of the most high-profile examples (New York Times, 23 May 2021).

The political crisis in Belarus is unlikely to abate in the second half of 2021. The regime has shown little desire to make even superficial changes to assuage demonstrators, and no willingness to make any significant changes. Likewise, the Russian government has shown no sign of backing down in its support of Lukashenko, despite Western states taking increasingly strong stances against him.

While large-scale demonstrations have been successfully repressed by the regime, smaller demonstrations continue across the country. Nevertheless, while there may be periodic surges in demonstration levels, without a shift in Lukashenko’s regime stability, it is unlikely that current demonstration and repression dynamics will shift in the short term. Yet the country’s political situation still remains highly unstable in the long term. Lukashenko’s actions have only ensured his immediate hold on power. In coming years, as economic pressure wears on the regime and as Lukashenko gets closer to retirement, the popular democratic protest movement that began in 2020 may regain momentum.

Further reading:

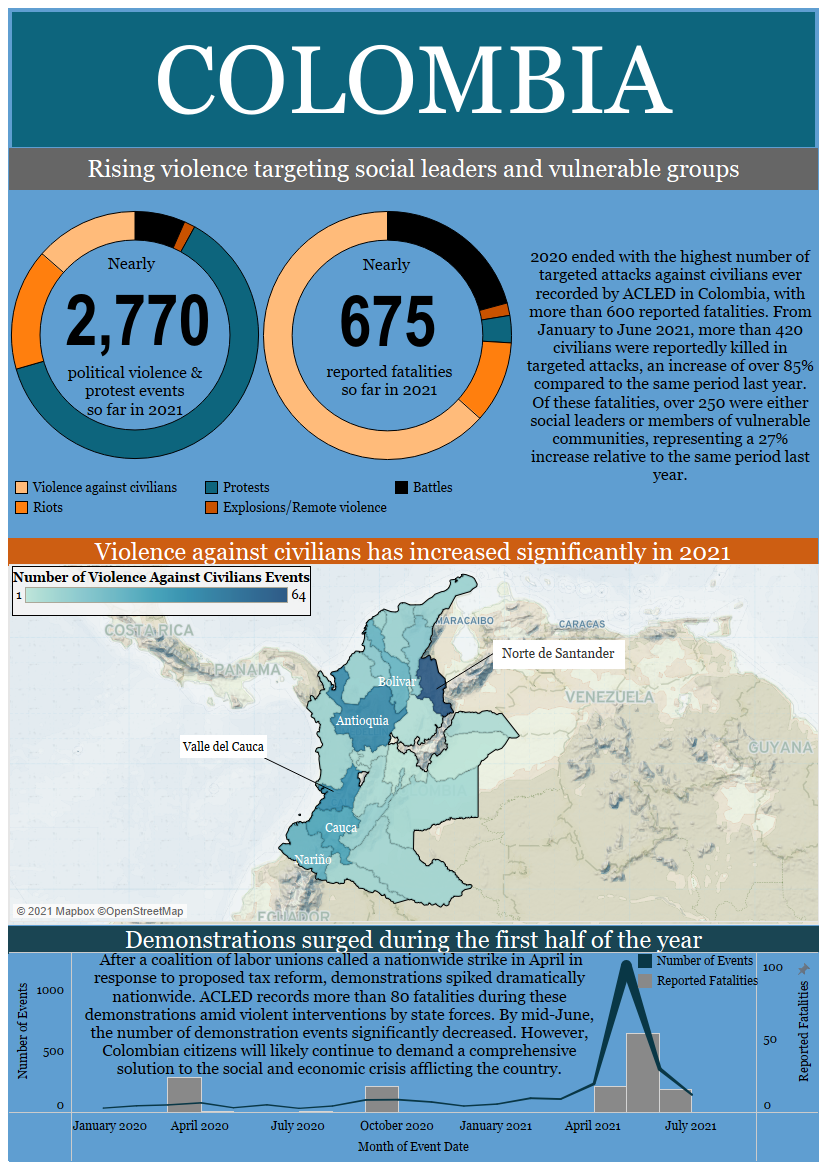

2020 ended with the highest number of targeted attacks against civilians ever recorded by ACLED in Colombia. These attacks resulted in over 600 reported fatalities, the majority of whom were social leaders or members of vulnerable groups, such as farmers or Indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities. From January to June 2021, ACLED records over 420 civilian fatalities from targeted attacks, more than 250 of whom were either activists or rural residents. This is a more than 85% increase in total civilian fatalities from targeted attacks compared to the same time period last year, and a 27% increase in killings of social leaders or members of vulnerable communities. This is the highest number of reported fatalities from targeted attacks on these groups recorded in Colombia during the first six months of the year since the beginning of ACLED coverage in 2018.

The government’s inability to fully implement the peace agreement signed with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) in 2016 is often cited as a key factor contributing to the rise in killings (Al Jazeera, 24 November 2020; International Crisis Group, 6 October 2020). The power vacuum left by the dismantling of the FARC has led to the expansion of other groups, such as the National Liberation Army (ELN) and the Gulf Clan, a drug trafficking organization composed of former paramilitary cells. Armed groups often clash in rural areas near farmers’ villages or near Indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities. Meanwhile, social leaders are active at the local-level in promoting development projects in their communities, and are often targeted by armed groups due to their role in curbing criminal and violent activity. The FARC has also splintered into several dissident groups, which compete for territory and control of illegal markets, raiding areas where they can cultivate coca and marijuana crops, or where they can use routes to transport drugs to other countries. Social leaders and vulnerable communities are often seen by armed groups as obstacles to these activities.

In 2020, restrictions associated with the coronavirus pandemic also increased the vulnerability of rural communities. Quarantine measures meant that many local activists were left alone inside their communities and homes, often without protection or bodyguards, putting them at risk of intimidation by armed groups. Although the Colombian government relaxed quarantine restrictions in 2021, it did not advance any measures to increase the protections for social leaders and vulnerable groups. In the Norte de Santander department, for example, at least 25 social leaders or members of vulnerable groups have been killed thus far in 2021 — a number already higher than that reported during the entirety of 2020. There is intense conflict in Norte de Santander, especially in the Catatumbo region, between several armed groups, including FARC dissidents, former paramilitaries, and criminal gangs. On 25 June 2021, gunmen fired multiple bullets at a helicopter transporting President Iván Duque as it landed in Cúcuta municipality, after a visit to the Catatumbo region. In a recently released video, a dissident faction of the FARC, the Magdalena Medio Bloc, claimed responsibility for the attack (El Espectador, 25 July 2021).

At the start of 2021, ACLED found that groups — particularly Indigenous communities and farmers — faced high risks of displacement from conflict. During the first half of 2021, the Colombian Ombudsman’s Office recorded the displacement of more than 30,000 people from 181 different communities (Defensoría del Pueblo, 4 June 2021), exceeding the total reported during the entirety of 2020 (Defensoría del Pueblo, 7 January 2021), indicating that vulnerable communities continue to be severely affected by intense conflict between different armed groups.

Apart from targeted attacks increasing in the first half of 2021, the rate of fatalities reported overall is also on the rise. In 2020, over 820 fatalities were reported over the course of the year. Halfway through 2021, there have already been reports of nearly 675 fatalities across the country. Conflict continues as armed groups and gangs fight for territorial control of disputed areas and state forces try to combat their activities.

The increasing number of fatalities is also linked to the targeting of protesters during clashes with police amid massive anti-government demonstrations. Although the Duque government has only recognized 24 deaths directly connected to the demonstrations, ACLED data indicate that more than 80 fatalities have been reported, based largely on documentation from local NGOs, such as Indepaz (Indepaz, 28 June 2021). Demonstrations started on 28 April when the National Strike Committee (CNP, Comité Nacional del Paro, in Spanish), a coalition of different labor unions, called for a nationwide strike in response to proposed tax reform. The fiscal reform proposed by Duque would increase taxation on basic commodities and would lower the exemption limit for income taxes (BBC Mundo, 29 April 2021). The government eventually withdrew the proposal due to the backlash. Nevertheless, demonstrations continued with an expanded focus encompassing discontent with policies on health, education, and other social issues. Greater protections for social leaders are also a frequent topic of demonstrations given mounting dissatisfaction with the government’s inability to address the effects of decades-long conflict. Thousands of labor unionists, students, teachers, farmers, and civil society organizations took to the streets for several weeks during the late spring, amid a growing economic crisis exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic (Reuters, 29 April 202; New York Times, 18 May 2021).

While more than 80% of all demonstrations were peaceful, demonstrators engaged in violence, vandalism, and clashes with security forces in several instances. The violent intervention of the Mobile Anti-Disturbances Squadron police force (ESMAD) in response to the demonstrations was criticized by human rights organizations. In some cases, demonstrations were met with lethal force, resulting in estimates of over 80 fatalities connected to the unrest, including approximately 40 demonstrators.3The total number of demonstrator fatalities may be higher, as it is often unclear if the remainder of those reported killed — which contribute to the over 80 fatalities currently coded by ACLED as having been killed during this period, based largely on documentation from local NGOs — were protest participants or bystanders. For more on ACLED fatality methodology, see this FAQ. At least two police officers were reported killed during the demonstrations, while multiple civilians not involved in protesting have also been targeted and killed (Human Rights Watch, 9 June 2021). A recent report by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) accuses state forces of using disproportionate and excessive force against protesters (CNN, 8 July 2021). Overall, ACLED records more than twice as many excessive force events against peaceful protesters during the first half of 2021 than during the entirety of the previous three years.

The protest movement led to a dramatic increase in the total number of demonstration events across Colombia. There were nearly 10 times more demonstration events recorded in May 2021 than in any other month over the past three years. However, by mid-June, the number of demonstration events had dramatically decreased, especially after the government cleared major roadblocks that had been set up by demonstrators. On 15 June, the CNP announced it would be formally suspending protest activity until 20 July, though some groups such as students and Indigenous organizations indicated that they did not agree with the decision and continued to demonstrate. On 20 July, coinciding with Colombian Independence Day, the CNP resumed massive demonstrations across the country (El Espectador, 21 July 2021). Colombian citizens will likely continue to demand a comprehensive solution to the social and economic crisis afflicting the country, and social unrest is expected to persist until old grievances deriving from the failure to fully implement the guidelines from the 2016 peace accord are met.

Further reading:

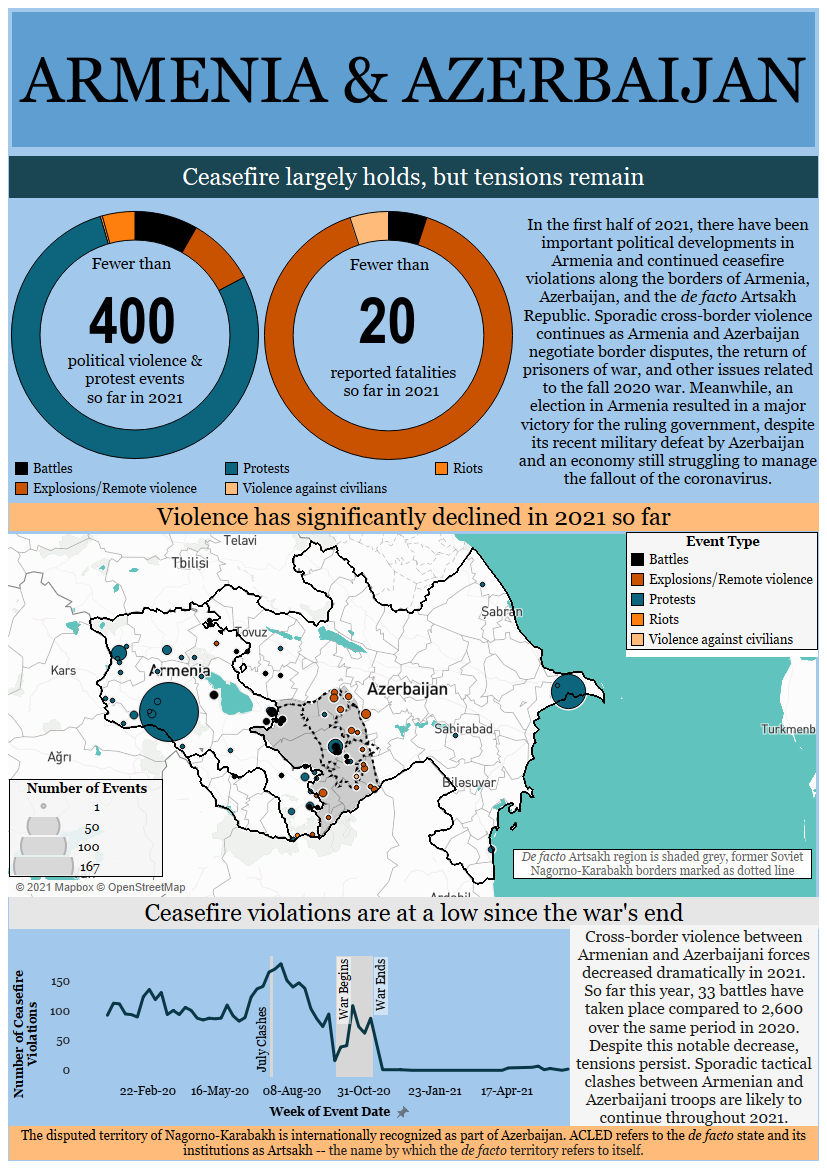

In the first half of 2021, important political developments occurred in Armenia, and continued ceasefire violations took place along the borders of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and the de facto Artsakh Republic.4The disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh is internationally recognized as part of Azerbaijan. ACLED refers to the de facto state and its institutions as Artsakh — the name by which the de facto territory refers to itself. For more on methodology and coding decisions around de facto states, see this methodology primer. As warned at the start of the year, sporadic cross-border violence has continued, if only at relatively low levels. Meanwhile, Armenia and Azerbaijan continue negotiations about the border dispute, the return of prisoners of war (POWs), and other issues related to the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war. Contrary to previous assessments, the Armenian political situation has become relatively stable following a decisive electoral victory for the government in June. This victory came despite the government’s recent military defeat by Azerbaijan and an economy still struggling to manage the fallout of the coronavirus pandemic.

Conflict between Azerbaijan, Armenia, and the de facto Republic of Artsakh remained low during the first half of 2021. Cross-border violence between Armenian and Azeribaijani forces decreased dramatically in 2021 relative to the year prior. Between January and June 2021, 33 clashes took place, compared to 2,600 during the same period in 2020. The decrease in fighting has been ensured by the presence of Russian peacekeeping troops in key areas of Armenia and Artsakh, who were deployed following the ceasefire of 9 November 2020 (Reuters, 10 November 2021).

Despite this notable decrease, tensions remain over lingering issues from the war. These include disputes over borders, mapping information for minefields, POWs, and the recognition of the de facto Republic of Artsakh. While negotiations over some of these issues have not made much visible progress, there have been successes. Particularly prominent among these are negotiations between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the return of Armenian POWs in exchange for Armenian information about the location of minefields in territory captured by Azerbaijan. Since the 9 November ceasefire, 88 POWs have been returned to Armenia, the last two groups of which were returned in exchange for maps of minefields in the Agdam, Fizuli, and Zangilan regions (Azatutyun, 13 June 2021). Discussions over these topics are likely to continue for some time as the two sides use prisoners and minefields for political leverage. There are reportedly over 100 Armenians still held by Azerbaijan, suggesting that such exchanges may continue (Azatutyun, 13 June 2021).

Meanwhile, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan’s Civil Contract party won a decisive victory in parliamentary elections on 20 June 2021. Pashinyan ran a campaign focused on recovering from the recent military defeat and continuing his party’s popular anti-corruption and modernization initiatives (Prime Minister of Armenia, 21 June 2021). Former President Robert Kocharyan’s party, Armenia Alliance, was the main competition for Civil Contract. Despite the recent defeat of Armenian forces under a Civil Contract government, Armenia Alliance was unable to generate enough public support to defeat Pashinyan, likely a result of the corruption allegations Kocharyan has faced over the years (Carnegie Moscow Center, 6 October 2018). Pashinyan’s party won close to 54% of the vote, with Kocharyan’s party trailing at 21% (DW, 21 June 2020). All other parties received vote percentages too small to enter parliament, though the ‘I Have Honor’ alliance was admitted in order for a third party to be present, as legally required (Factor, 21 June 2021).

Sporadic clashes between Armenian and Azeribaijani troops are likely to continue throughout the second half of 2021, as they have so far this year. Negotiations on the future of Nagorno-Karabakh and the outcome of the war are also unlikely to make major progress. The status of the remaining territories controlled by the de facto Artsakh Republic continues to be disputed, which may drive some small surges in fighting, as has happened sporadically along the frontline since the ceasefire. Meanwhile, tension over the opening of regional roads and railways, which was initiated by the 9 November agreement, will continue, especially given Azerbaijan’s insistence on having a ‘corridor’ through the Syunik region of Armenia despite the Armenian government’s refusal to broach any such discussion (Azatutyun, 21 April 2021).

In the long term, the military situation may come to resemble the front before the 2020 war, with sporadic surges in fighting for tactically or strategically significant ground. However, unlike the period prior to the 2020 war, major offensive operations are extremely unfeasible for both sides. The deployment of Russian peacekeeping troops to Armenia has ensured that offensive action by Azerbaijan will be effectively impossible without massively increasing tensions with Russia and provoking a Russian military response. Meanwhile, the Armenian army is currently incapable of offensive action as it was severely damaged by the war, and was already militarily weak relative to Azerbaijan’s forces (Al Jazeera, 1 October 2020). Since the ceasefire, Azerbaijan and Turkey have expanded their military cooperation, acting as a further deterrent to Armenia. With this situation unlikely to change, there is little chance that either side will resume major offensive operations similar to those seen in 2020.

Further reading:

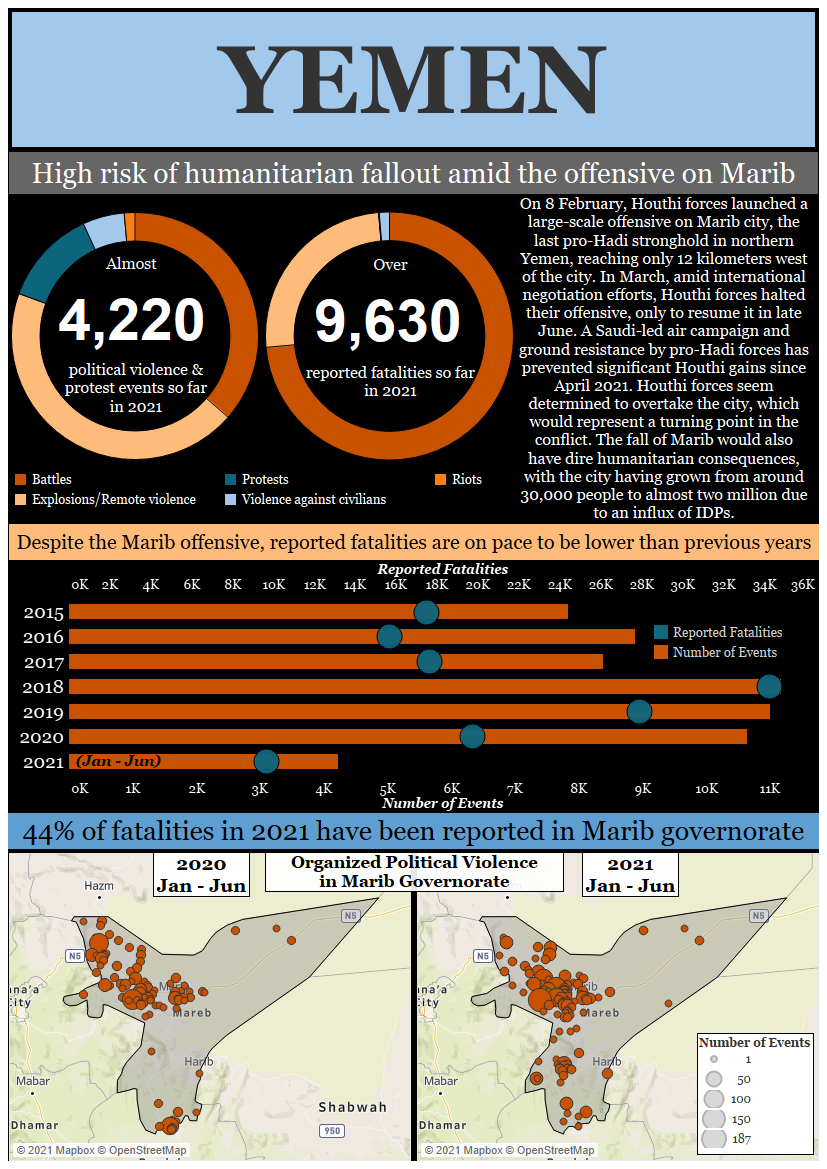

At the beginning of the year, ACLED assessed that the limited successes of pro-Hadi forces on the battlefield in 2020 would make it unlikely for Houthi forces to agree to a ceasefire or an inclusive peace process in Yemen. In February 2021, Houthi forces launched a large-scale offensive on Marib city, the last stronghold of the Hadi government in northern Yemen. They reached areas within 15 kilometers west of the city, before halting their offensive in May, amid unprecedented international efforts to find a political solution to the conflict. The Houthis resumed their offensive again in late June.

At the time of writing, Houthi forces have not yet taken control of Marib. Due to a sustained air campaign by the Saudi-led coalition and resistance on the ground by pro-Hadi tribes and military forces, the Houthis have achieved no significant gains since April 2021. Houthi forces seem determined to overtake the city nevertheless, as this would represent a turning point in the conflict, possibly one of no return. From Marib city, Houthi forces would be able to move eastwards and take control of the Safer oil and gas facilities, which would represent a major blow to the coffers of the Hadi government.5According to ACAPS, the loss of crude oil exports from Marib by the Hadi government would amount to at least USD 19.5 million per month (ACAPS, 26 July 2021). This new territory would also open new possible routes towards southern Yemen through the Shabwah governorate. Finally, the fall of Marib to Houthi forces would have devastating humanitarian consequences. Over the course of the conflict, the city’s population has grown from around 30,000 people to almost two million due to the influx of internally displaced persons (IDPs) from other governorates (Crisis Group, 17 April 2020). According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), an assault on the city could displace 385,000 people (IOM, 15 February 2021).

The inauguration of President Joe Biden at the start of this year has led to a sharp turn in American policy towards the Yemen conflict. In his first visit to the State Department, President Biden called for an end to the war, announced the end of American support for the Saudi-led military intervention, and appointed a special envoy for Yemen, Timothy Lenderking (Associated Press, 5 February 2021). As ACLED predicted at the beginning of the year, however, the end of already negligible US support has so far had little effect on the current trajectory of the war.

Less than two weeks after these announcements, the US State Department officially revoked the designations of the Houthis as a “Foreign Terrorist Organization” and a “Specially Designated Global Terrorist Group,” in “recognition of the dire humanitarian situation in Yemen” (US Department of State, 12 February 2021). The revocation of these designations — initially made by the administration of former President Donald Trump and then suspended by the Biden administration in January 2021 — arguably prevented devastating humanitarian consequences (ACAPS, 14 January 2021).

This renewed US engagement, however, has been initially perceived by the Houthis as a sign of weakness. The Houthi offensive on Marib was launched less than a week after the appointment of US Special Envoy Lenderking, leading some to argue that Biden’s purported efforts to end the war may actually intensify it (ISPI, 26 April 2021). Still, since May 2021, political violence decreased significantly in Marib: ACLED records a monthly average of 132 political violence events across May-June in the governorate compared to 225 across February-April. This was the result of unprecedented engagement of international actors in support of the peace process, which saw renewed Houthi participation in negotiations, as well as a notable change in Oman’s role from being a facilitator of the process to being its mediator (Middle East Eye, 10 June 2021).

In late June, only a few days after Martin Griffiths gave his last briefing to the UN Security Council as the UN special envoy for Yemen (OSESGY, 15 June 2021), Houthi forces renewed their offensive on Marib — yet another failure of the diplomatic track. As a way to alleviate pressure on Marib city, pro-Hadi forces then launched an offensive against Houthi forces in Al Bayda governorate. This worked temporarily, leading in early July to the most violent week ever recorded in Al Bayda since the start of ACLED’s Yemen coverage in 2015. Houthi forces were quick to reverse a number of pro-Hadi territorial gains, however, and fighting in Marib has since flared up again. As a new UN special envoy has yet to be officially appointed at time of writing,6Swedish diplomat and current EU ambassador to Yemen Hans Grundberg is expected to take over from Martin Griffiths over the summer. Martin Griffiths was appointed as the new UN Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator in May 2021. renewing the political process between the Houthis and the Hadi government will not be easy (The Washington Institute, 1 July 2021).

In southern Yemen, the new UN special envoy will need to focus on the Riyadh Agreement that was signed in November 2019 under the auspices of Saudi Arabia to solve the conflict between the Southern Transitional Council (STC) and the Hadi government. In December 2020, the STC agreed to join a power-sharing government with President Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi in exchange for allowing the government to move back into Aden, the interim capital. At the beginning of the year, ACLED identified this as a potential opportunity for the southern secessionists and the Hadi government to unify against Houthi forces.

So far this has not materialized. After a hopeful end to 2020, the relationship between the two parties has only deteriorated. Joining a power-sharing government at the national level does not seem to have removed STC secessionist ambitions. STC-affiliated forces are notably still very much under STC control, instead of the defense and interior ministries, as per the military provisions of the Riyadh Agreement. In June 2021, these forces stormed several Hadi-aligned newspapers in Aden with the reported goal of establishing ‘Aden News Agency for the State of South Arabia’ (Al Masdar, 2 June 2021; Committee to Protect Journalists, 9 June 2021). That same month, the STC also made unilateral military appointments and designated its own foreign representatives to a number of countries.

Following the increase in tensions between the two parties, Saudi Arabia was quick to convene talks between the STC and the Hadi government on 2 July to reaffirm both parties’ adherence to the Riyadh Agreement. On the same day, however, clashes erupted between pro-Hadi and STC forces in Abyan governorate over control of Lawdar district security department. Tensions between the two camps then escalated further, as pro-Hadi forces repressed protests organized throughout southern governorates on 7 July to commemorate the 1994 “Southern Invasion Day” (South24, 6 July 2021). As ACLED assessed at the start of 2021, the success or failure of the Riyadh Agreement remains critical for the future of the war — though success appears less likely today.

Finally, while successful negotiations between Saudi Arabia and the Houthis over border insecurity could lead to a significant decrease in the Saudi war effort, negotiations have made little progress during the first half of 2021. In March, the Houthi leadership rejected a Saudi offer for a nationwide ceasefire. A new development in 2021, however, is ‘secret’ talks being held between Iran and Saudi Arabia in Iraq since April. During these talks, the Saudi government reportedly asked Iran to stop Houthi attacks on the kingdom in exchange for helping sell Iranian oil in international markets (Middle East Eye, 13 May 2021). ACLED data show that Houthi attacks indeed decreased for four consecutive weeks across May and June 2021, only to pick up again afterwards. What these direct talks between Iran and Saudi Arabia can achieve with regard to the broader Yemeni conflict remains to be seen.

Further reading:

- Little-Known Military Brigades and Armed Groups in Yemen: A Series

- The Myth of Stability: Fighting and Repression in Houthi-Controlled Territories

- The Wartime Transformation of AQAP in Yemen

- Yemen’s Fractured South: ACLED’s Three-Part Series

- Inside Ibb: A Hotbed of Infighting in Houthi-Controlled Yemen

- Yemen Snapshots: 2015-2019

- Yemen’s Urban Battlegrounds: Violence and Politics in Sana’a, Aden, Ta’izz and Hodeidah

- ACLED Methodology and Coding Decisions around the Yemen Civil War

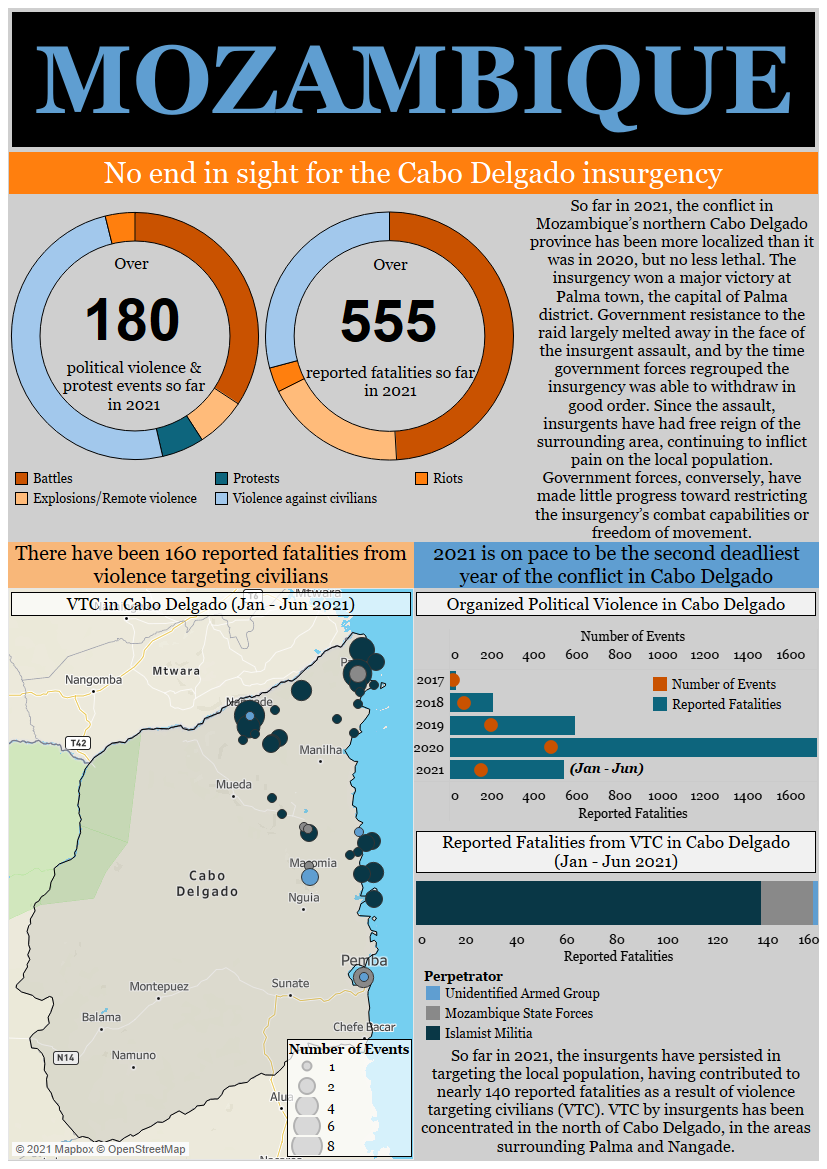

So far in 2021, the conflict in Mozambique’s northern Cabo Delgado province has been less geographically widespread than it was in 2020, but no less lethal. The Islamist insurgency that has operated in the province since October 2017 has maintained its strength and added another district capital to its record of major settlements raided. At the same time, the conflict has become more internationalized, with the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and Rwanda both authorizing military deployments to the conflict zone to support Mozambican government forces. The humanitarian crisis that the conflict has precipitated continues to expand. An April report from the International Organization for Migration (IOM) records the number of people displaced due to the conflict at over 720,000 across Cabo Delgado and Nampula provinces, up from over 660,000 at the end of 2020 (IOM, April 2021).

In many respects, ACLED’s concerns about the Cabo Delgado conflict in 2021 have been borne out. The report at the start of the year noted that the Mozambican government lacks a clear strategy for winning the conflict militarily, and would struggle to reduce the insurgency’s military capacity. In March 2021, the insurgency won a major victory at the eponymous capital of Palma district, which hosts liquified natural gas projects that the Mozambican government hopes will be the key to the country’s economic future (Cabo Ligado, 30 March 2021). Government resistance largely melted away in the face of the insurgent assault and, by the time government forces regrouped, the insurgents were able to withdraw. The insurgents have continued to threaten the surrounding area ever since (Cabo Ligado, 29 June 2021).

Government forces, conversely, have made little progress toward restricting the insurgency’s combat capabilities or freedom of movement. The greatest progress government troops have made is in reoccupying and holding Diaca, a strategically located town in Mocimboa da Praia district that will be crucial to any eventual effort to retake Mocimboa da Praia town from the insurgency (Cabo Ligado, 26 May 2021). The insurgent occupation of Mocimboa da Praia town in August 2020 remains the most substantial insurgent victory of the conflict, and the Mozambican government has not been able to re-establish control (Cabo Ligado, 16 September 2020).

Indications that Mozambique would relent in its opposition to international intervention in the conflict has also proven accurate to an extent. The report at the start of the year assessed that the US and European countries would likely be the main sources of pressure for intervention. The US has stepped up its counterterrorism programming with Mozambique by designating the insurgency a “Foreign Terrorist Organization” and a “Specially Designated Terrorist Group” and launching another round of Joint Combined Exchange Training missions in the country (Cabo Ligado, 16 March 2021; 11 May 2021; US Department of State, 10 March 2021). The European Union is expected to announce its own training mission soon (Cabo Ligado, 6 July 2021). Yet neither have offered to engage in direct security provision in Cabo Delgado. Instead, it is the SADC that has consistently pressured Maputo to accept a regional intervention force, finally prevailing at a June summit (Cabo Ligado, 29 June 2021). The details of the SADC deployment are not yet clear, but it appears it will be operating much closer to the front lines than US or European trainers. In addition to the SADC deployment, Mozambique also negotiated a deployment of 1,000 Rwandan military and police to Cabo Delgado to, in the words of the Rwandan government, “conduct combat and security operations, as well as stabilisation and security sector reform” (Government of Rwanda, 9 July 2021).

Some trends in the country have deviated from considerations noted in the report at the start of the year. Following the insurgency’s incursions into Tanzania in October 2020, the report indicated that insurgent attacks may continue across Mozambique’s northern border, yet that has so far not taken place. Outside of an isolated incident on 17 February at Mahurunga in Kitaya Ward, there have been no indications of insurgents from Cabo Delgado launching attacks in Tanzania, and no claims of any such attacks. Instead, Tanzania’s primary role in the conflict in 2021 has been the “soft refoulement” of Mozambican refugees fleeing insurgent attacks in Palma district (Cabo Ligado, 16 June 2021). Rather than being housed in Tanzania, Mozambicans seeking refuge in Tanzania are instead shipped west and deported back to Mozambique at a border post in Mueda district.

The report also noted expectations that the Mozambican government would increase its reliance on private military contractors (PMCs) in 2021. Instead, Mozambican police allowed their contract with South African PMC Dyck Advisory Group to lapse in April (Cabo Ligado, 6 April 2021). The government has not employed any private fighters since, aside from a small group of Ukrainian pilots flying Mi17 and Mi24 helicopters that Mozambique purchased from the South African arms company Paramount (Cabo Ligado, 30 March 2021). Instead, Mozambique has worked to expand its own military capabilities, contracting Paramount and its partner Burnham Global to purchase military equipment and to train Mozambican soldiers on the new platforms (Cabo Ligado, 30 March 2021). That project has come along slowly, but Gazelle helicopters piloted by newly trained Mozambicans began to see combat in late May (Cabo Ligado, 1 June 2021).

There is still no clear path to a resolution of the Cabo Delgado conflict in the near future. The insurgency’s ability to carry out major operations appears undented, and it remains to be seen if added domestic capabilities and foreign intervention can give the Mozambican government a decisive military advantage in the conflict. In the meantime, local grievances against the government grow as the humanitarian situation in the province worsens, potentially driving conflict well into the future.

Further reading:

- Weekly and monthly reports from ACLED’s Cabo Ligado conflict observatory

- CDT Spotlight: Escalation in Mozambique

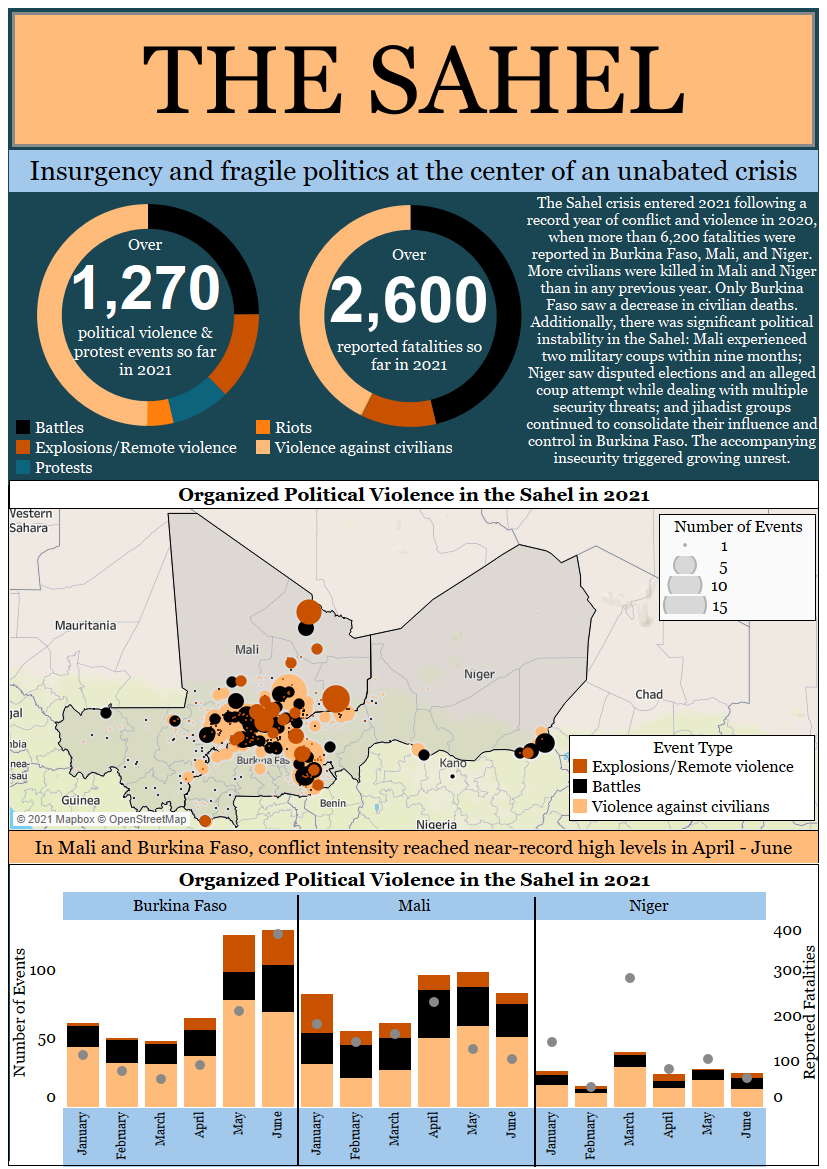

The Sahel crisis entered 2021 following a record year of conflict and violence in 2020, during which more than 6,200 fatalities were reported in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. In 2020, more civilians were killed in Mali and Niger than in any previous year, and only Burkina Faso saw a decrease in civilian deaths. Thus far in 2021, jihadist groups continue to consolidate their influence and control in Burkina Faso, while also expanding their activities to other countries, such as the Ivory Coast (Le Monde, 7 July 2021) and Benin (ACLED & Clingendael, 10 June 2021), and becoming a threat to Ghana (3news, 15 June 2021). Additionally, there has been significant political instability in the Sahel: Mali experienced two military coups within the nine months between August 2020 and May 2021 (Le Monde, 31 May 2021); Chadian President Idriss Deby Itno was killed amid a rebel incursion into Chad from neighboring Libya in April 2021 (La Croix, 20 April 2021); and disputed elections and an alleged coup attempt were held in Niger in March 2021 (Courrier International, 1 April 2021). These developments underscore the continuation and intensification of the fragile politics and unabated crisis in the Sahel that ACLED highlighted earlier this year.

In 2020, relations between the Al Qaeda-affiliated Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) and Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) deteriorated into a full-blown turf war. However, in 2021, the jihadi-on-jihadi fighting did, as expected, gradually decline as both JNIM and ISGS faced sustained external pressure from the French-led Operation Barkhane (ISPI, 3 March 2021), especially in the tri-state border region (ie. Liptako-Gourma). Instead, JNIM and ISGS have shifted their efforts to geographic areas beyond the immediate reach of external forces in other parts of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, where they regularly attack ethnic-based militias and self-defense groups — such as Dan Na Ambassagou in Mali, the Volunteers for Defense of Homeland (VDP) in Burkina Faso, and fledgling militias in Niger — as well as the communities supporting these groups (for more, see this recent ACLED report).

While 2020 was the deadliest year on record in the Sahel, the first six months of 2021 show a similar trajectory of perpetual and escalating cycles of violence. In Burkina Faso, conflict reached record levels in May and June, with the two deadliest attacks ever reported in the country. The attacks targeted civilians and the Burkinabe police, respectively, and occurred in Solhan and Bilibalogo. The escalation in Burkina Faso follows the collapse of a fragile ceasefire between state forces and JNIM, which had been in place throughout most of 2020. In eastern Burkina Faso, JNIM-affiliated fighters have also pressured and isolated communities in several small towns and villages, including in Mansila, Tankoualou, Tanwalbougou, Kpenchangou, and Madjoari, imposing embargoes that impede movement and commerce (Menastream, 5 July 2021).

The steadily deteriorating security situation in Burkina Faso has led to widespread unrest. In June, thousands of people demonstrated in the towns of Dori, Titao, and Kaya (Le Monde, 28 June 2021). Widespread demonstrations, led by the political opposition, have followed in early July, with demands for improved security for the population and adequate support for the Defense and Security Forces (FDS) and the VDP. While the Burkinabe armed forces have stepped up their efforts through numerous military operations throughout the country, they have not sufficiently weakened the capacities of the jihadist groups. The largely reactive and transient nature of their operations make them predictable, hence only causing very temporary disruptions.

In Mali, similar to in Burkina Faso, conflict reached near-record high levels between April and June 2021. The political upheaval following a second military-led coup in May 2021, nine months after a previous coup in August 2020, did little to alleviate Mali’s precarious position as a regional conflict epicenter. Rather, it strained relations with Mali’s main military partner, France, which is leading the counter-militancy alliance against jihadist groups in the Sahel. As a result of the second coup, France suspended its joint military operations with Malian forces (RFI, 3 June 2021). While these operations resumed only a month later (Al Jazeera, 3 July 2021), the suspension highlighted France’s increasingly problematic position in supporting controversial and undemocratic regimes (Le Figaro, 4 June 2021).

Both Mali and Burkina Faso have engaged in negotiations with jihadist groups with varying degrees of state involvement, and with limited success. In Mali, for example, the Ministry of National Reconciliation assigned a delegation from the High Islamic Council of Mali (HICM) to facilitate the talks in Farabougou. Meanwhile, in Burkina Faso, the National Intelligence Agency (ANR) negotiated with JNIM. Many agreements, however, were negotiated directly between local communities and JNIM militants. In a June 2021 report, ACLED evaluated the fragility and difficulty of sustaining these local agreements. One such ceasefire agreement in Farabougou — which took effect in April 2021 after a six-month embargo by Katiba Macina militants, who are part of JNIM (Mali 24 Info, 18 April 2021) — was revoked by the group in early July. Hostilities between Katiba Macina militants and Bambara hunters are now rapidly resuming (aBamako, 5 July 2021). The embargo tactic is an integral part of the jihadist strategy, and just as in eastern Burkina Faso, the militants in Mali also use this tactic in other places, such as Dinangourou, Mondoro, Petaka, and Bandiagara.

Just halfway into 2021, in Niger, ISGS have been responsible for the highest number of civilian deaths by a single armed actor in the country in any year since the beginning of ACLED coverage in 1997. Their increased targeting of civilians has largely been prompted by the formation of self-defense groups by villagers in northern Tillaberi and Tahoua — in response to ISGS attacks and the government’s failure to protect them. The group has also carried out a series of deadly attacks against Nigerien forces. In reaction, Nigerien forces and French forces of Operation Barkhane conducted joint operations between Tillaberi, in Niger, and Menaka, in Mali. The joint force scored a series of tactical victories against ISGS in June, killing and capturing several ISGS commanders, and thereby degrading some of the group’s senior leadership (Le Point, 2 July 2021). Since the French-Nigerien operations, under the name ‘Solstice,’ took place largely on Malian soil, it seems that France has found in the Nigeriens a partner suited to take on a larger role. Indeed, it seems that France intends to make Niger a central pillar, both at the operational and logistical level, as part of the transformation of its Sahel mission (Jeune Afrique, 9 July 2021). Niamey is set to host the new command and control center of the Task Force Takuba.

The death of Chadian President Idriss Deby Itno, a key strategic partner of France, further weakened the alliance to combat militancy in the Sahel. France also announced, on 10 June, the end of Operation Barkhane, which has been in place since August 2014, along with a gradual withdrawal of troops stationed in the Sahel, and the closure of bases in northern Mali (Le Point, 9 July 2021). This is part of a transformation of French efforts in the Sahel aimed at building a broader coalition with greater burden-sharing with other European countries as part of Task Force Takuba. Meanwhile, they are seeking more support from, and cooperation with, the US, as the two countries signed a new agreement that will allow French and American special operators to work more closely together on counterterrorism operations in Africa (Defense One, 9 July 2021). The transformation of the French military mission involves targeting jihadist leaders, concentrating efforts on the tri-state border region, and the southward encroachment of the militant threat.

Another dimension is the ‘Sahelization’ of the larger effort, in which Sahelian states take greater responsibility for their own security. In June, a series of simultaneous joint operations were conducted over vast territories in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger with a rather unprecedented level of coordination, involving troops from Burkina Faso, Chad, France, Mali, Niger, and the Ivory Coast (Menastream, 20 June 2021). These operations could be seen as a test-run of an emerging ‘Sahelization’ dynamic. However, it is questionable whether local state forces will be able to maintain a sufficient level of coordination and to sustain these types of operations over the longer term, given logistical challenges and a lack of critical intelligence capabilities and aircraft.

Further reading:

- Sahel 2021: Communal Wars, Broken Ceasefires, and Shifting Frontlines

- The Conflict Between Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State in the Sahel, A Year On

- Mali: Any End to the Storm?

- In Light of the Kafolo Attack: the Jihadi Militant Threat in the Burkina Faso and Ivory Coast Borderlands

- State Atrocities in the Sahel: The Impetus for Counterinsurgency Results Is Fueling Government Attacks on Civilians