From the Capitol Riot to the Midterms: Shifts in American Far-Right Mobilization Between 2021 and 2022

6 December 2022

After the attack on the Capitol in January 2021 and through the November 2022 midterm elections, far-right mobilization has only continued to evolve in the United States. Currently, far-right activity in 2022 is on track to exceed the level of activity reported in 2021, driven by a significant uptick in white nationalist, white supremacist, and anti-LGBT+ organizing around the country. This report analyzes shifts in the drivers of far-right mobilization over the course of the year, with a focus on how these drivers shaped the activities of armed militias and violent groups like the Proud Boys in states with contentious elections, as well as a look at trends to watch ahead of the 2024 campaign season.

Key Trends

Far-right militia and militant social movement activity in 2022 is on track to exceed the level of activity reported in 2021.

- Approximately 750 events — including demonstrations, acts of political violence, and training, recruitment, and propaganda activities — involving far-right groups have been recorded as of late November 2022, compared to nearly 780 events in all of 2021.

- Far-right groups are linked to high rates of protest violence: demonstrations involving far-right militias and militant social movements are nearly five times more likely to turn violent or destructive than other demonstrations.

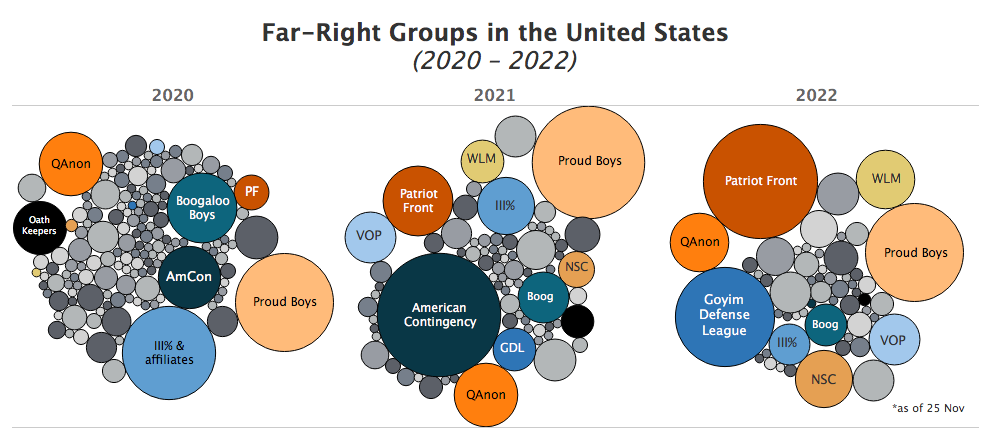

Overall activity has risen even as the landscape of far-right actors has continued to become more defined, with fewer distinct groups active in 2022 than 2021.

- While the far right is not a monolith and many actors are highly competitive with one another, far-right activity is increasingly coalescing around specific groups and issues.

- At least 56 distinct groups have been active this year, down from 83 last year and 159 in 2020.

- An exception to this trend is Arizona, where more far-right groups have been active this year than in 2021. Arizona is home to the most far-right activity of any state, driven by particularly high rates of recruitment and vigilantism.

White supremacy/white nationalism is the top driver of far-right protest activity this year.

- So far in 2022, 21% of demonstrations involving far-right groups have been driven by white supremacy/white nationalism, up from 15% last year.

- White nationalist/white supremacist actors like Patriot Front and the Goyim Defense League are among the groups that have most substantially escalated their activities.

Anti-LGBT+ mobilization, the second most salient driver, has fueled the largest increase in far-right protest activity this year.

- So far in 2022, 14% of demonstrations involving far-right groups have been anti-LGBT+, up from less than 3% last year.

- Though not limited to organized far-right actors, these groups have taken an increasingly large role in anti-LGBT+ mobilization around the country: far-right groups have engaged in over three times more anti-LGBT+ demonstrations than they did last year (55 events in 2022, up from 16 events in 2021), and in three times as many states (18 in 2022, up from six in 2021).

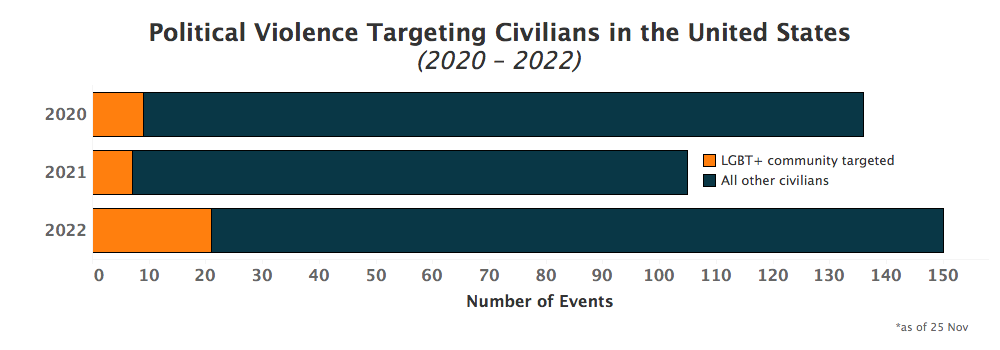

Acts of political violence against the LGBT+ community have contributed to a wider surge in violence targeting civilians, with the number of incidents reported in 2022 already surpassing the total number recorded last year.

- At least 150 incidents of violence targeting civilians have been reported in the United States this year, with more than 20 specifically targeting the LGBT+ community. This is up from over 100 total events last year, with at least seven targeting the LGBT+ community.

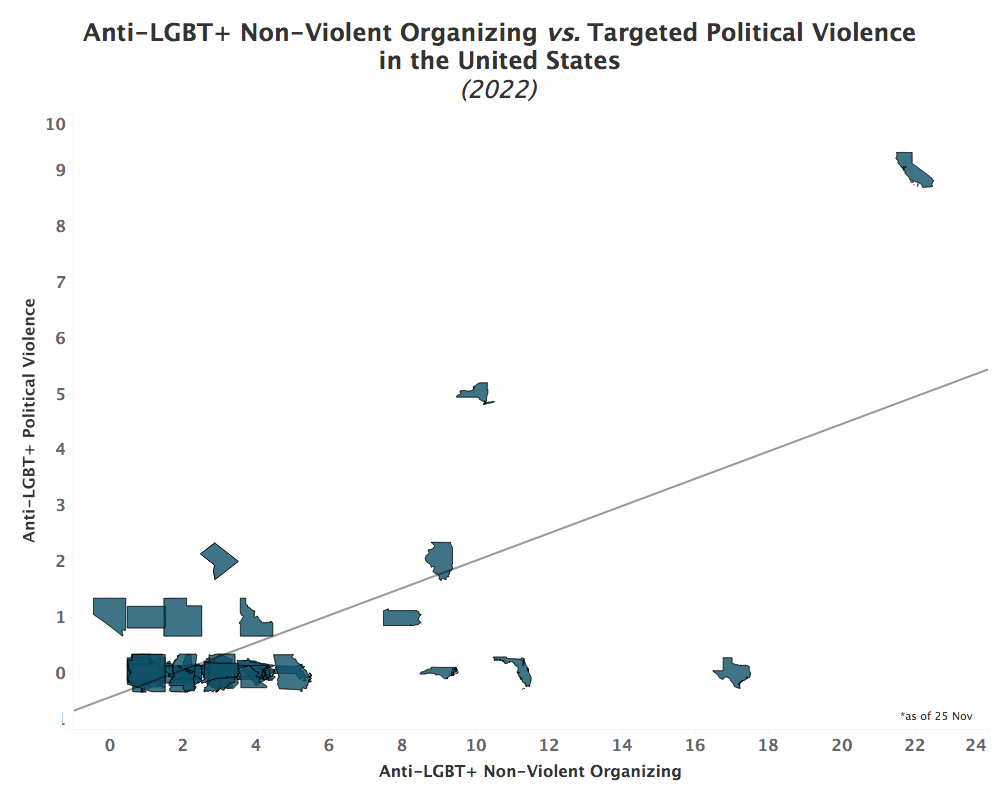

- In states with increasing levels of non-violent anti-LGBT+ organizing, the rise in anti-LGBT+ protests and offline propaganda has correlated positively and strongly (r = 0.67) with an increase in political violence targeting members of the LGBT+ community.

These drivers played a prominent role in shaping far-right activity in states with competitive races during the midterm elections, to varying degrees of electoral success. Where far-right candidates were defeated — often corresponding to places where mobilization strategies offered fewer opportunities for the far right to come together, network, and build alliances — drivers are likely to shift in the coming months ahead of the 2024 campaign season.

- Former President Donald Trump’s campaign announcement could reinvigorate certain sectors of the far right, such as groups like the Proud Boys. Over 100 pro-Trump demonstrations have already taken place around the country this year, even prior to his announcement, and approximately a quarter have involved far-right actors.

Introduction

Following the January 2021 Capitol riot and leading up to the November 2022 midterm elections, far-right mobilization in the United States continued to evolve. The American far right is made up of a variety of actors, including armed militias (e.g. Oath Keepers, Three Percenters), street-fighting organizations and hate groups (e.g. Proud Boys, Patriot Front), and a wide array of more loosely organized movements (e.g. Christian nationalists; QAnon conspiracy theorists; gun rights extremists).1Militias and militant social movements are defined in the ACLED dataset as non-state (often armed) groups or movements with members affiliated by ideology, identity, or community. They at times operate at the behest of political figures, and the former are typically characterized by higher levels of structure, schedule, and strategy than the latter. The vast majority of active militias and militant social movements currently active in the United States are oriented on the far right of the political spectrum. These far-right groups also account for the majority of militia and militant social movement activity, including violence. Not all militias and militant social movements are far-right, however; this category also includes left-wing groups as well as actors that do not fall cleanly into either category. For more information, see this ACLED report and check the interactive map of militia and militant social movement activity at our United States Country Hub. Far-right politicians, activists, and media figures must rely on a range of different strategies to bring these disparate groups, movements, and populations together, and to mobilize them during important political periods, like elections. Current trends suggest that these efforts — while failing to achieve significant electoral victories for the Republican party during the midterms — have indeed been effective in spurring widespread mobilization: far-right activity2Defined as political violence, demonstrations, and non-violent strategic developments. is on track to be higher again this year than it was last year,3As of 25 November, 748 events have been reported. This puts 2022 on track to exceed the 778 events reported in 2021, if current trends continue through the end of the year. The 778 events last year mark an increase from 671 events reported in 2020. even as the landscape of far-right actors has continued to become more defined as fewer distinct groups have remained active (see figure below). Though the far right is not a monolith, with many actors remaining highly competitive with one another, this suggests that far-right activity has been coalescing around certain groups and issues.

Strategies that mobilize support — especially those that bring together multiple groups or subsets of the larger base — are successful and will spread among activists, politicians, and the media. Those that are less effective in generating sustained mobilization may be retired as new strategies and drivers of activity emerge in their stead. Which strategy or which driver may be most effective will vary by both time and space, with some drivers proving effective in one state more so than in another, for example — a function of the political environment, and the groups, actors, and populations that are present in that location. Further, as environments change, so too must the strategies used by groups if they are to adapt to the new context.

The strategies and drivers that fuel far-right activity are often inherently exclusionary, oriented around targeting a marginalized ‘other’ — sometimes explicitly for violence. These targets have included political opponents labeled as ‘communists’ and ‘socialists,’ the Black community, the Jewish community, the Muslim community, the LGBT+ community, women, and immigrants, amongst others. Even when such mobilization strategies fail to achieve certain key goals — like election victories — they can still fuel a rise in contentious activity and can increase the risks of political violence faced by these targeted communities.

This year, for example, as a resurgence in anti-LGBT+ rhetoric and organizing (e.g. demonstrations) began to escalate ahead of Pride Month in June — anchored by a renewed focus on the supposed threat to children posed by the LGBT+ community — both far-right and mainstream right-wing candidates integrated the strategy into their campaigns in an attempt to fire up the base and generate enthusiasm ahead of the midterms (PBS, 20 May 2022; 19th News, November 2022; Bloomberg, 10 October 2022). While in many cases this line of attack failed to drive voters to the polls (ABC News, 10 November 2022), it proved effective in fomenting violence against the LGBT+ community. In states that did see high levels of anti-LGBT+ organizing around the midterms, the uptick in activity was correlated with a similar spike in anti-LGBT+ political violence. This suggests that the places that see the highest levels of anti-LGBT+ organizing (i.e. where people protest against LGBT+ rights, or show up to disrupt LGBT+ events, or engage in propaganda distribution), are also the places where the LGBT+ community is at heightened risk of targeted political violence, underlining the relationship between mobilization drivers and violent outcomes.

In short, in contexts where certain mobilization strategies have been effective, those strategies will likely continue to be used — with those same targeted populations remaining at high risk for associated violence. In other contexts, where the political environment has changed or prior drivers are not (or are no longer) effective, additional strategies and drivers are likely to (re)emerge — potentially ratcheting up the risk for other marginalized and targeted communities. Understanding these dynamics can help stakeholders identify and monitor evolving risks to their communities and allow them to develop effective means of mitigating these risks.

Evolving Drivers of Far-Right Activity

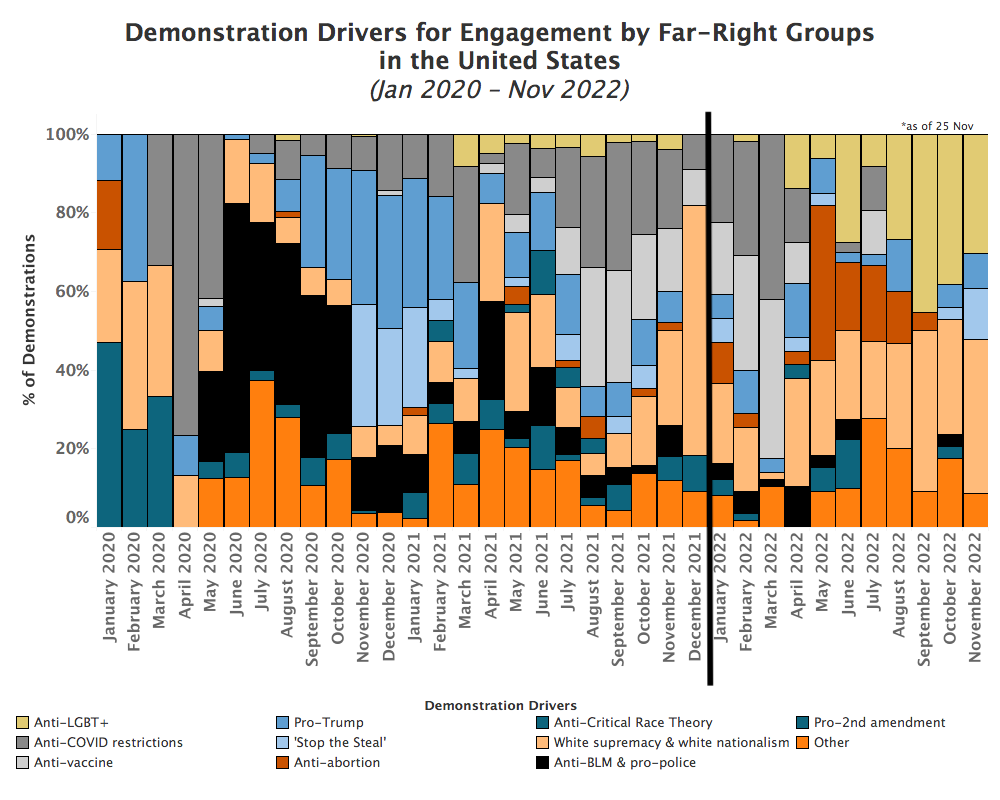

A variety of drivers have shaped far-right protest activity in 2022. These include, for example, opposition to pandemic-related public health restrictions and policies, including anti-vaccine mobilization, in the form of ‘Freedom Convoys,’ especially at the start of the year (in dark and light gray, respectively, on graph below), and anti-abortion mobilization, especially in the spring, around the time of the Supreme Court Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision (in brown). The graph below depicts the evolution of these different drivers for demonstrations involving far-right groups over time, with an emphasis on 2022, following previous trends analyzed by ACLED earlier this year. Far-right actors — here referring to far-right militias and far-right militant social movements — are defined as non-state (often armed) groups or movements with members affiliated by a far-right ideology, identity, or community. Militias and militant social movements at times operate at the behest of political figures, and the former are typically characterized by higher levels of structure, schedule, and strategy than the latter.4Far-right groups are often characterized by violent opposition to equality or democracy and preference for nationalism, empire, racial or ethnic supremacy, extreme support for capitalism and human competition, or other exclusionary orientations (e.g. opposition to advancements for women, religious minorities, racial or ethnic minorities, immigrants, trans or gender non-conforming people, etc.). Hate groups, groups that have an ‘anti-communism’/‘anti-Marxist’/‘anti-socialist’ stance, or a semi-veiled ‘anti-globalist’ stance directed at people rather than goods or money would also fall under this category. Such extremism broadly comes from a defense of social hierarchies (itself the converse of ‘equality’ and ‘democracy’), and can be observed in several different ways, including ultra-nationalism, conservative religious zealotry, fascist ideologies of different stripes, and pro-capitalist libertarianism. For more, see ACLED’s joint report with MilitiaWatch: Standing By: Right-Wing Militia Groups and the United States Election.

Two drivers that have increasingly shaped the majority of demonstration activity involving far-right groups in recent months have been continued support of white supremacy and white nationalism (in peach on graph above), which first gained particular salience late last year, and anti-LGBT+ mobilization (in tan on graph above), which began to surge in summer 2022. These two drivers played a prominent role in shaping far-right activity in states with competitive races during the midterm elections, to varying degrees of electoral success. These drivers are explored in further detail below.

White Supremacy and White Nationalism

Nationally, white supremacy and white nationalism together constitute the most salient driver of far-right protest activity overall so far in 2022, marking the continuation of a trend that began late last year. White supremacist/white nationalist demonstrations include events in which protesters specifically advocate white supremacist and/or white nationalist ideals (e.g. ‘White power!’), as well as those in which white supremacist or white nationalist groups, including neo-Nazi groups, take part (e.g. Goyim Defense League, Nationalist Social Club, the Ku Klux Klan, etc.). The rate of engagement in protests related to this driver is higher this year than it was last year (21% of demonstrations involving far-right groups in 2022, up from 15% last year). Even as the landscape of far-right actors has become more defined over time (see bubble chart above), white nationalist/white supremacist organizations, like Patriot Front and the Goyim Defense League, have been among the groups that have most substantially escalated their activities. While such activity has been directed against a number of marginalized communities, the stark rise in antisemitism (New York Times, 4 November 2022) has contributed considerably to this trend.

White supremacy/white nationalism is a significant driver of far-right activity in states like Ohio, for example, which was home to a competitive Senate race between Trump-endorsed Republican J.D. Vance and moderate Democrat Tim Ryan. In the lead-up to the election — in fact, since the start of the year — every demonstration involving far-right groups in the state had been oriented around white supremacy/white nationalism. For example, on 16 April, people gathered for a protest in Lancaster in support of ‘White Lives Matter’ as part of a national day of action. In late October, individuals associated with the white nationalist group Patriot Front gathered in Youngstown, where they held a banner reading “Reclaim America” and handed out flyers promoting their group. In some cases, white supremacist groups tried to integrate events linked to other drivers as well, in efforts to reach a wider audience:on 12 February, for example, a group of people, some of whom were armed with with semi-automatic rifles and handguns, gathered in Marysville to demonstrate in favor of ‘White Lives Matter,’ while holding signs promoting 9/11 conspiracy theories as well as conspiracy theories related to the coronavirus pandemic (“COVID is an attack on white western society”)(Union County Daily Digital, 12 February 2022). One individual in attendance noted how ‘activists’ had “come from all over Ohio” (Union County Daily Digital, 12 February 2022). The use of similar framing by far-right candidates, like Republican Vance, underlines how politicians may adopt narratives that have proven useful in organizing. In his campaign’s opening television ad, for example, Vance asks, “Are you a racist? Do you hate Mexicans?” before arguing that loose border policies were there to ensure “more Democrat voters pouring into this country” (New York Times, 16 May 2022). This type of organizing appeared to be effective in Ohio: Republican Vance ultimately won the election.

New Hampshire too was the site of a competitive Senate race, in this case between incumbent Democrat Maggie Hassan and MAGA candidate Republican Don Bolduc. Similar to in Ohio, all demonstrations involving far-right groups in the state in the months leading up to the election had also been around white supremacy/white nationalism — contributing to the rise in activity by far-right groups in New Hampshire more largely. For example, in mid-September, members of the Nationalist Social Club Granite State 131 demonstrated in Hampton as well as in Portsmouth with signs promoting the Nationalist Social Club reading ‘Defend White New England.’ Unlike in Ohio, however, far-right mobilization around this driver did not seem to have a positive impact on Bolduc’s campaign, as Democrat Hassan was able to hold onto her seat. Since the election, white nationalist groups in the state have begun to adopt new branding around which to mobilize — specifically, the anti-LGBT+ narrative. On 13 November, a group of people — including armed white nationalists, Proud Boys, and Christian groups — gathered for a protest at Teatotaller Cafe and Bakery in downtown Concord during a Drag Queen Story Hour, against transgender and LGBT+ rights, ‘grooming,’ and the ‘sexualization of children’ (New Hampshire Public Radio, 14 November 2022; Concord Monitor, 14 November 2022). This branding has thus far proven more successful in bringing together disparate groups and subsets of the Republican base than organizing around white supremacy and white nationalism in the state.

Anti-LGBT+ Mobilization

While white supremacy/white nationalism may be the most salient driver of far-right protest activity overall so far in 2022, anti-LGBT+ organizing5ACLED only collects data on physical activity; non-physical threats, harassment, or intimidation incidents that do not escalate into physical violence, or occur outside of physical demonstrations or propaganda events, are not captured. Please see the ACLED Codebook and Resource Library for more information about ACLED’s catchment and event type definitions. has contributed to the starkest increase in far-right activity this year (14% of demonstrations involving far-right groups in 2022 have been anti-LGBT+, up from less than 3% last year). Anti-LGBT+ demonstrations have been on the rise across the country more broadly, with over 130 demonstrations already this year, up from nearly 60 last year, and six in 2020. These demonstrations are also taking place in more and more states: this year, they have been reported in 36 states and Washington, DC; up from 21 states and Washington, DC, last year; and six states in 2020. What is especially worrying about this trend is that the rise in non-violent organizing — i.e. demonstrations and offline propaganda (such as flyering or banner drops) — against the LGBT+ community in these states has correlated positively and strongly (r = 0.67) with an increase in political violence6Political violence includes acts of sexual violence, non-sexual attacks, and mob violence. The ACLED dataset is not a crime dataset. While some hate crimes may be included in the dataset, not all hate crimes will meet ACLED’s threshold for serious acts of physical, political violence. Other datasets with different methodologies may arrive at different figures. Please see the ACLED Codebook and Resource Library for more information. targeting members of the LGBT+ community (see figure below).

Such targeted political violence is not limited solely to spaces where offline non-violent organizing is common, however, as tools like social media help to widen the reach of anti-LGBT+ rhetoric and spread narratives and tactics beyond geographic borders. With the role of social media platforms in the dissemination of mis-/disinformation — aggravated by ineffective content moderation policies and failures to quell the spread of false claims and conspiracy theories — the anti-LGBT+ narrative has reached far beyond the areas that have seen the highest concentration of offline activity. For example, an LGBT+ club in Colorado Springs, Colorado, was the site of a mass shooting in November that is currently being prosecuted as a hate crime (AP, 6 December 2022).7On 6 December 2022, the suspect was charged “with 305 criminal counts including hate crimes and murder.” While anti-LGBT+ protests had taken place in Colorado in the months prior — such as an anti-drag protest in Highlands Ranch on 17 June 2022 (Twitter @HeidiBeedle, 17 June 2022) — such organizing had been relatively more limited in comparison to other states in the lead-up to the deadly incident. Acts of political violence targeting the LGBT+ community have contributed to a wider surge in violence against civilians in the United States, with this year’s levels already surpassing those recorded last year (see graph below).

Though not limited to organized far-right actors, far-right groups in particular have taken an increasingly large role in anti-LGBT+ activity: so far this year, far-right groups have engaged in over three times more anti-LGBT+ demonstrations than they did last year (at least 55 demonstration events in 2022, up from 16 events in 2021), and in three times as many states (18 states in 2022, up from six states in 2021).

North Carolina, for example, was home to a competitive Senate race between MAGA candidate (and current Representative) Republican Ted Budd and Democrat Cheri Beasley. In the months leading to the election, almost all demonstrations involving far-right groups were anti-LGBT+. Anti-LGBT+ rhetoric has long been salient in North Carolina: the state was home to some of the first ‘bathroom bills,’ denying access to public bathrooms based on transgender identity (CNN, 24 March 2016). The driver proved to be an effective means in attracting multiple subsets of the Republican base in the state — specifically, church groups and the far-right Proud Boys. In fact, in half of the anti-LGBT+ demonstrations involving the Proud Boys during this time, the group attended protests alongside Christian groups. For example, on 21 June 2022, a group of people, including members of the Cape Fear Proud Boys and several local church groups, protested outside of a public library in Wilmington holding a Pride-themed storytime event, with reports of the Proud Boys also entering the library and yelling at attendees, including children (WWAY TV3, 22 June 2022; Twitter @ErinInTheMorn, 22 June 2022). On 24 September 2022, counter-protesters, including church members and Proud Boys, showed up to oppose a drag event held in Albemarle (Twitter @gwen_fulton, 24 September 2022). Such events proved useful in providing ways to also boost recruitment: on 30 October, for example, dozens of Proud Boys demonstrated in Sanford in opposition to a drag brunch being held at a local brewery, and despite the organizer of the drag brunch calling police to ask for security after Proud Boys members verbally harassed attendees, the Proud Boys were able to use the opportunity to pass out recruitment pamphlets (ABC11, 30 October 2022; Twitter @JordanGreenNC, 30 October 2022). Republican Budd’s electoral win suggests that mobilization around this driver may have been an effective strategy in the state for the right. Since then, Senator-elect Budd, currently a Representative, voted against the Respect for Marriage Act in the House, which seeks to codify same-sex marriage (The News & Observer, 16 November 2022).

Nevada too was home to a competitive Senate race: between incumbent Democrat Catherine Cortez Masto, the first Latina ever elected to the Senate, and Republican Adam Laxalt. The only demonstration involving a far-right group in Nevada thus far this year was in opposition to LGBT+ rights. On 26 June 2022, a group of Proud Boys demonstrated outside of the library in Sparks against a Pride event that was taking place inside, which included a drag story time for children. At least one person at the demonstration was armed with a rifle and approached a group of participants, who then ran into the library after a panic. Members of the Proud Boys yelled at library staff and participants, including children (News4, 26 June 2022). As mobilization was more limited, and failed to foster a means for bringing populations together, it did not seem to be an effective strategy for the right in Nevada. Democrat Cortez Masto won the election after days of vote-counting — delivering control of the Senate for the Democrats.

In Georgia, like in Nevada, the only demonstration involving a far-right group since the fall was in opposition to LGBT+ rights. On 1 October, a dozen or so Proud Boys gathered in Columbus to rally against a Gay Pride event (Twitter @afainatl, 3 October 2022). As such mobilization has been more limited and has not brought together distinct populations, it is not yet clear how effective the strategy will be for the right in Georgia. While it may have helped secure the governorship for incumbent Republican Brian Kemp in a much-watched gubernatorial race against Democrat Stacey Abrams — especially given Kemp’s appearances at multiple anti-LGBT+ summits and conventions (WABE, 27 October 2022) — its efficacy in the competitive Senate race will only come further into focus after the results of the runoff between incumbent Democrat Reverend Raphael Warnock and Trump-backed Republican Herschel Walker on 6 December 2022. Walker has positioned himself as increasingly anti-LGBT+: in October he blasted the prospect of transgender people serving in the military (WABE, 27 October 2022), while in the lead-up to the runoff, days after the deadly Colorado Springs shooting, he put out a new campaign ad advocating for transgender women and girls (who he refers to as “biological males”) to be barred from competing on women’s sports teams (The Hill, 21 November 2022).

Unlike the states noted above, in which a single driver played a prominent role in the mobilization of far-right groups in the lead-up to the election, in Florida, both support for white supremacy as well as opposition to the LGBT+ community played significant roles in mobilizing far-right groups in the lead-up to the midterms — which together contributed to the rise in the activity of far-right groups in the state this year. Florida was home to both a competitive Senate race — between incumbent Republican Marco Rubio and Democrat Val Demmings, who had been a shortlist vice presidential candidate for now-President Joe Biden — as well as a high-profile gubernatorial race — between incumbent Republican Ron DeSantis, a frontrunner for the Republican candidacy in the next presidential election, and Democrat Charlie Crist. Rubio has shown consistent lack of support for the LGBT+ community (Human Rights Campaign, 24 October 2022), while DeSantis has been a leading figure in the latest anti-LGBT+ push, ushering in the first wave of ‘Don’t Say Gay’ legislation (NPR, 28 March 2022) nationally. DeSantis has also increasingly ‘flirted’ with Christian nationalism (Miami Herald, 26 September 2022) — which many Americans equate with or link to white supremacy (Pew Research Center 27 October 2022; Center for American Progress, 13 April 2022) — failing to denounce the display of swastikas and other Nazi imagery by his supporters (Rolling Stone, 26 July 2022). Wins by both Rubio and DeSantis helped to make Florida one of the few success stories for Republicans this midterm election.

Mobilization strategies have been the most effective when they create opportunities for far-right groups to come together, network, and build alliances — and Florida is a good example of this. For instance, on 30 January 2022, more than a dozen demonstrators affiliated with different white nationalist groups, National Socialist Movement and Patriot Front, gathered at the Daryl Carter Parkway overpass in Orlando to rally in support of neo-Nazi ideology by waving a swastika flag and unfurling a banner with the phrase “Let’s Go Brandon” (an anti-Biden slogan) (MyNews13, 31 January 2022; Twitter @afainatl, 4 February 2022). On 23 July 2022, more than 100 people, including members of the white nationalist National Socialist Florida and the white supremacist Goyim Defense League, who carried flags with Nazi swastikas and megaphones with Infowars stickers, gathered for a demonstration and marched to the Tampa Convention Center in Tampa during the 2022 Turning Point USA convention, in support of Governor DeSantis (News4Jax, 24 July 2022; Orlando Weekly, 25 July 2022; Twitter @GoadGatsby, 23 July 2022). Given the apparent success of this strategy on election day, such organizing has only continued. On 15 November 2022, demonstrators gathered outside of Mar-a-Lago, former President Donald Trump’s private club residence in Palm Beach, to celebrate Trump’s 2024 campaign announcement (Twitter @FordFischer, 16 November 2022a). Affiliates of the Proud Boys and Nick Fuentes’ Groypers were among those present (Creative Loafing Tampa, 16 November 2022); some demonstrators promoted the QAnon conspiracy theory, with some also chanting derogatory anti-LGBT+ slurs at a counter-demonstrator (Twitter @FordFischer, 16 November 2022b).

Other Drivers

Despite the current dominance of white supremacy/white nationalism and anti-LGBT+ mobilization, these are not the only drivers of far-right activity, as shown in the initial bar graph above. Far-right actors, like all political actors, adopt mantles that may prove the most useful to them in their organizing, with the utility of drivers shaped by the current (local) political environment. As political environments are often in flux, the most salient drivers of activity are constantly changing — as a function of actors seeking to best adapt to that current context. While white supremacy may have been useful for far-right groups organizing in Ohio, anti-LGBT+ mobilization proved more helpful in allowing for coalition-building and organizing in North Carolina, for example.

In Arizona, in the autumn lead-up to the election, far-right groups did not take part in any demonstrations — instead engaging in other kinds of activity. In mid-October, for example, members of the Yavapai County Preparedness Team (YCPT), in coordination with the Lions of Liberty (LOL) and Clean Elections USA, a group which follows QAnon conspiracies, coordinated volunteers to watch ballot drop boxes and take pictures of voters and their license plates in Mesa, in a campaign of suspected voter intimidation, which they named Operation Drop Box (AZ Mirror, 31 October 2022). Groups of people gathered at ballot drop boxes in Mesa to watch voters several times around this date (Vice, 6 October 2022). The YCPT and LOL later said that they had decided to ‘stand down’ the operation after both groups were named in a federal lawsuit (AZ Mirror, 31 October 2022).

The lack of engagement by far-right groups in demonstrations should not be taken to signal more limited far-right activity in the state, however. Rather, Arizona is home to the most activity by far-right militias and militant social movements thus far this year, with more than 130 total events. The rate of far-right activity in Arizona is 23% higher than more populous California (home to nearly 110 events this year) and 139% higher than Texas (home to nearly 60 events this year). High levels of recruitment and vigilante activity contribute to these trends. In fact, the continued rise in recruitment activity by militias and other far-right actors in the United States (over 90 events thus far in 2022, up from almost 70 last year) has been driven primarily by groups in Arizona (92% of all recruitment by far-right groups thus far this year has taken place in the state). This includes recruitment by groups like the YCPT and LOL, which made their actions like ballot-box watching possible.

This has been a function of the environment in Arizona. While the landscape of far-right actors has become more defined over time across the country, with fewer distinct groups remaining active (see bubble chart at start of report), this trend does not hold in Arizona. In Arizona, more far-right groups have been active this year relative to last year (at least 19 distinct groups this year, up from 16 last year), with most increasing their activity between 2021 and 2022 (see chart below). More far-right groups have been active in Arizona this year than in any other state. This has been driven by the emergence of new groups, such as the Verde Valley Preparedness Team (VVPT) and the Chino Valley Preparedness Team (CVPT), both offshoots of the Oath Keepers;8The VVPT has engaged in 23 events thus far this year, while the CVPT has engaged in 15 events thus far this year; both were not active last year. increases in the activity of local groups, such as the AZ Patriots;9AZ Patriots have engaged in four events thus far this year, up from one last year. and increases in the activity of groups with a national presence, such as the Proud Boys and Three Percenters.10The Proud Boys have engaged in seven events thus far this year, up from one last year; the Three Percenters have engaged in six events thus far this year, up from two last year.

Such an environment — with high rates of activity, numerous active groups, and high levels of mobilization and recruitment — can be highly volatile. This is especially so in an environment like Arizona, which was home to a competitive Senate race between incumbent Democrat Mark Kelly and Trump-backed Republican Blake Masters, as well as a tight gubernatorial race between Democrat Katie Hobbs and Trump-backed Republican Kari Lake. Both races remained too close to call for days. While both Democrats have since won these contests, Lake — who had contributed to a culture of election denialism in the lead-up to the election, making her staunch support of the ‘Stop the Steal’ movement a core part of her platform — has since filed an election record suit and refused to concede the election, alleging without evidence that election laws were broken (AP News, 17 November 2022; CBS News, 25 November 2022).

Unsurprisingly, as the state had been home to considerable ‘Stop the Steal’ organizing following the presidential election of 2020, far-right groups have begun engaging in demonstrations again in recent weeks, specifically around the ‘Stop the Steal’ mantle. On 12 November, for example, a group of people, some armed, including affiliates of the Three Percenters and the Boogaloo Boys, gathered for a protest outside the Maricopa County Recorder’s office in Phoenix while votes were still being tallied inside, as part of the ‘Patriots Rise Up’ and in support of Lake (Twitter @MissTessOwen, 12 November 2022; News2Share, 13 November 2022; Twitter @NickMartin, 12 November 2022). Days later, on 14 November, a group of people, including at least one Three Percenter affiliate and at least one armed individual, gathered again outside the Maricopa County Tabulation & Election Center in Phoenix, in support of Lake (Twitter @JordanGreenNC, 15 November 2022). These trends in Arizona underline how the activity of far-right groups, and the drivers around which they mobilize, are a function of their local environment.

Conclusion

In short, the drivers of far-right activity evolve as groups adapt to their local environment and make decisions about the strategies that may prove most effective toward their goals. Understanding these dynamics is important, especially given the effect these drivers can have on violence, and particularly violence targeting marginalized communities.

The stark rise in anti-LGBT+ mobilization, and its efficacy in certain contexts in fueling activity and bringing together disparate groups — and fomenting violence — suggests that it is unlikely that this driver will be completely abandoned in the near term. In fact, it may foster closer ties between mobilized populations, such as evangelicals, Christian nationalists, and certain far-right groups. However, in many contexts it did not translate to electoral victory during the midterms, where it was ineffective in mobilizing mainstream Republicans and centrists (Holt, 14 November 2022; see, for example, Detroit News, 11 November 2022), and contributed to Republican defeats (Washington Post, 23 April 2022; Axios, 20 November 2022). It is likely, therefore, that the dominant national right-wing narrative strategy will again soon evolve as actors adapt to the post-election political environment, in hopes of a new mantle proving more effective in mobilizing audiences that the anti-LGBT+ narrative may have failed to inspire — especially in the lead-up to the 2024 presidential election.

This evolution may bring about the resurgence of old narratives, possibly reframed in novel ways, as was seen with anti-LGBT+ mobilization this year, which provides a clear example of old tropes repackaged in new ways. A further resurgence of white supremacy/white nationalism on the far-right, is also likely: the driver appeared to be effective in certain contexts in delivering votes (e.g. Florida, Ohio); groups organized around this ideology have already ratcheted up their activity; the driver remains salient across far-right actors at large; and the online environment is more primed than any other time in recent years to allow narratives built on mis-/disinformation and conspiracy theories to spread.

With Donald Trump announcing his intention to vie for the presidency in 2024 (New York Times, 16 November 2022), the time is ripe for new mobilization strategies on the right. His recent meeting with Kanye West, who made headlines for antisemitic statements, and white nationalist Nick Fuentes (CBS News, 26 November 2022), provide even stronger suggestion that a (re)surge(nce) in white nationalism and white supremacy may be imminent.

Over 100 pro-Trump demonstrations have already taken place around the country this year, even prior to his announcement, and these demonstrations have turned violent or destructive over three times as often as other demonstrations (2% of the time, compared to 0.6% of the time). Approximately a quarter of these events have involved far-right groups, with the remainder composed of unaffiliated individuals — resulting in an environment primed for co-option by far-right actors such as the Proud Boys, who have long been loyal to Trump (for more, see this ACLED Actor Profile). While many Trump-backed candidates performed poorly this election cycle, many of the states home to high rates of pro-Trump organizing did not have such decisions to make on their ballots, so the true hold he still has on right-wing politics — and far-right mobilization — remains to be seen.