The Muqawama and Its Enemies

Shifting Patterns in Iran-Backed Shiite Militia Activity in Iraq

23 May 2023

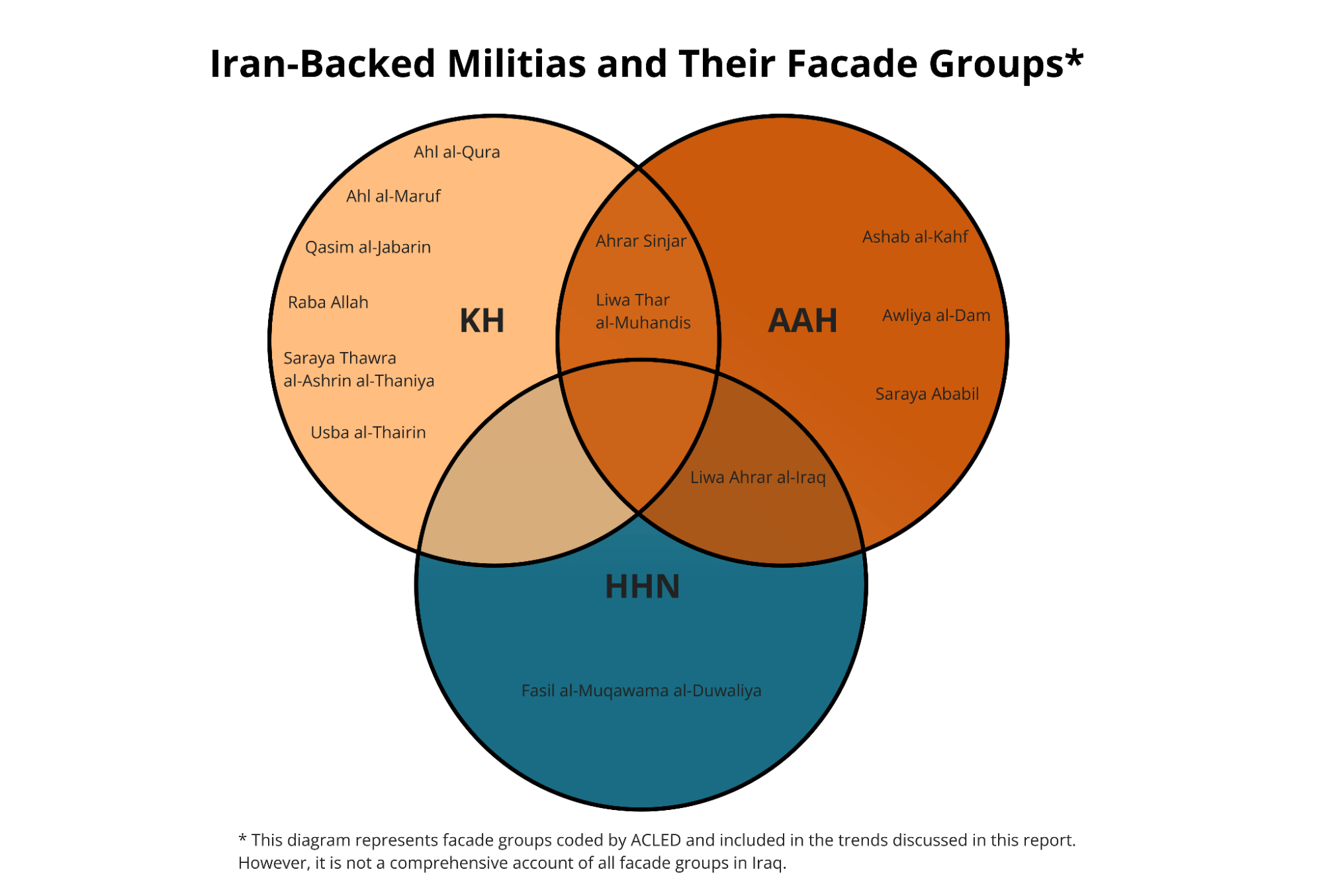

The post-2003 security landscape in Iraq has seen the proliferation of dozens of militias identifying with Shiite Islam. Many of these actors are integrated into the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) – a paramilitary group established in 2014 to counter the Islamic State and later incorporated into the Iraqi state forces – and have strong relations with the Iranian regime and its security apparatus.1International Crisis Group, ‘Iraq’s Paramilitary Groups: The Challenge of Rebuilding a Functioning State,’ 30 July 2018 These Iran-backed groups include prominent militias such as Kataib Hizbullah (KH), Asaib Ahl al-Haqq (AAH), and Haraka Hizbullah al-Nujaba (HHN), as well as a number of recently formed ‘facade groups’ like Ashab al-Kahf and Qasim al-Jabarin. Such facade groups are generally assumed to operate on behalf of KH, AAH, and HHN (see graph below). These groups are notable for portraying themselves as the Muqawama, or the ‘resistance’ against the United States and other foreign forces.

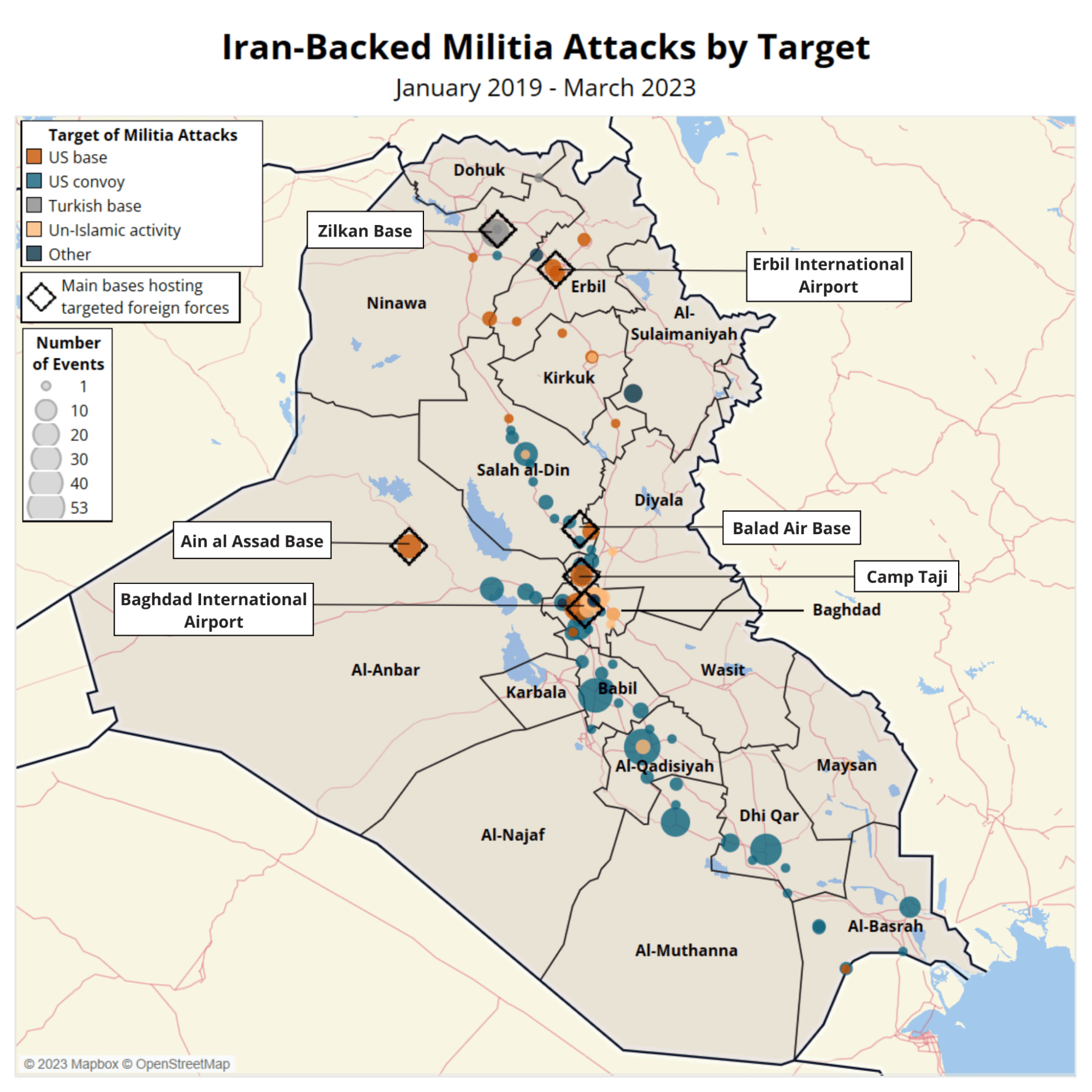

Since mid-2019 – and increasingly after US forces assassinated Iranian general Qassim Soleimani and PMF Deputy Chairman Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis in January 2020 – Iran-backed militias have engaged in military operations targeted at foreign and domestic objectives inside Iraq. ACLED records over 500 events involving these militias or one of their facade groups between June 2019 and March 2023. These attacks are carried out using drones, rockets, and IEDs and have three primary targets with a distinct geographical distribution: 1) convoys carrying materiel for US personnel and forces affiliated with the Global Coalition Against Daesh and bases hosting them, mostly clustered in central and southern Iraq; 2) Turkish bases, in northern Iraq; and 3) purported ‘un-Islamic’ activities, largely around Baghdad (see map below).

The activity of Iran-backed militias2‘Shiite militias’ is specifically referring to KH, AAH, HHN, and their facades. These three militias are well-established, Iran-backed, part of the PMF, generally participate in the Iraqi political process, and are most commonly associated with militancy against foreign forces and un-Islamic influences in the country. Other notable Shiite militias that meet most of this criteria exist, like Kataib Sayyid al-Shuhada and the Peace Companies, but they are not under the purview of this report as they are rarely, if ever, implicated in these types of attacks in the post-2020 period. has shifted between these three primary targets in response to a number of domestic and international drivers: US-Iran tensions; intra-militia competition; opposition to foreign military forces inside Iraq; and domestic political developments. This report explores the evolution in militia activity from 2019 to 2023 by interpreting these shifts as strategies to maximize pressure on foreign forces, avoid retaliation, and gain popular domestic consensus.

Attacks Against US and Coalition Targets

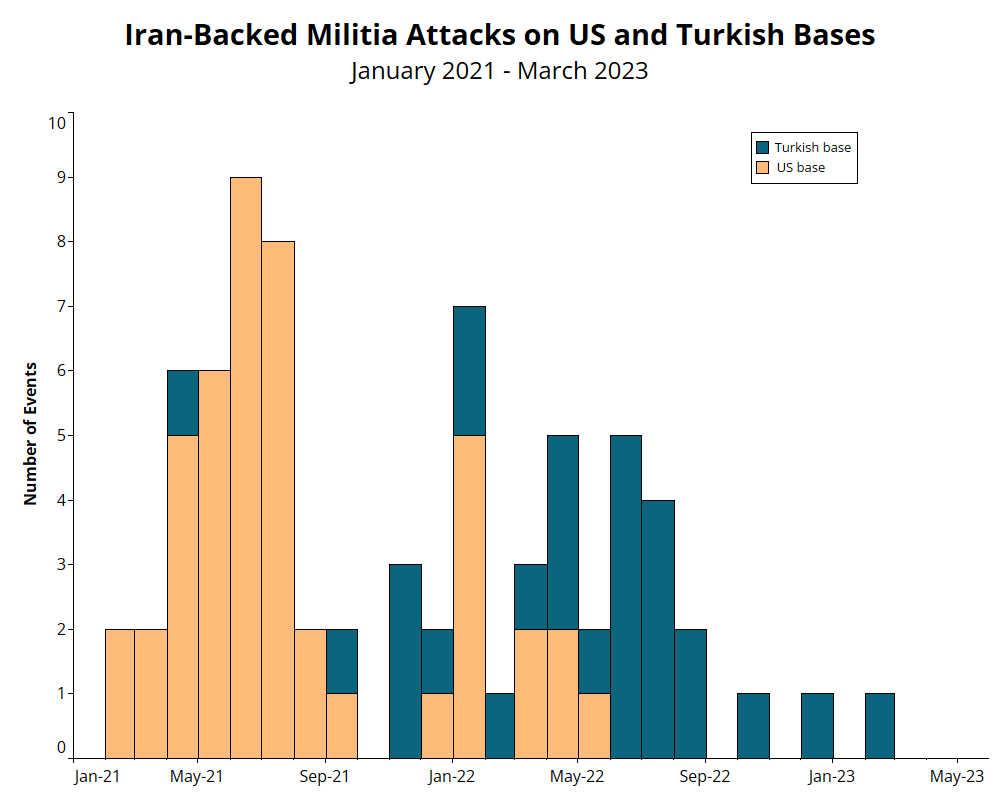

Iran-backed militias see the US as an occupying force interfering in Iraq’s internal affairs and undermining Baghdad’s sovereignty. Their operations are part of a wider campaign to pressure the US to exit Iraq and are aimed at two primary targets: military bases and convoys carrying logistical materiel (see graph below). Both these targets reflect a preference for indirect confrontation with US troops, and their respective prioritizations have fluctuated depending on the militias’ tactical objectives.

In Iraq, US and Coalition forces, advisors, and contractors are hosted by Iraqi government-administered military bases and at the US Embassy in Baghdad. Since mid-2019, ACLED records over 100 incidents involving Iran-backed militia operations against bases hosting US forces. Operations against bases require complex planning and make use of remote violence and Iranian-provided drones and weaponry.3Michael Knights, ‘Iraqi Militias Show Off Iranian Anti-Air Missile,’ The Washington Institute, 21 October 2021 Successful attacks have a high symbolic value, highlighting US vulnerabilities and affecting US public opinion. At the same time, operations against bases are riskier: they are more predictable, easier to prevent, and likely to trigger retaliation in the event of US casualties.

On the other hand, operations against convoys present a lower level of risk for the militias. Trucks are owned and driven by Iraqi contractors, so the possibility of US casualties is low, reducing the threat of US retaliation. Furthermore, these operations are difficult to anticipate and prevent. They typically occur along the convoy routes, in particular south of Baghdad, while transporting materiel to and from military bases around the capital. Albeit representing a form of low-level “harassment”4Seth Frantzman, ‘How attacks on US forces in Iraq became a new normal,’ Atlantic Council, 28 August 2020 against US forces, operations against convoys are considered an effective form of pressure against the US and an expression of anti-US sentiment.5Mehr News, ‘US military convoy comes under attack in Iraq,’ 12 July 2020 ACLED records approximately 330 convoy attacks since 2020, mostly involving IEDs and roadside bombs, which resulted in at least three reported fatalities of Iraqi nationals.

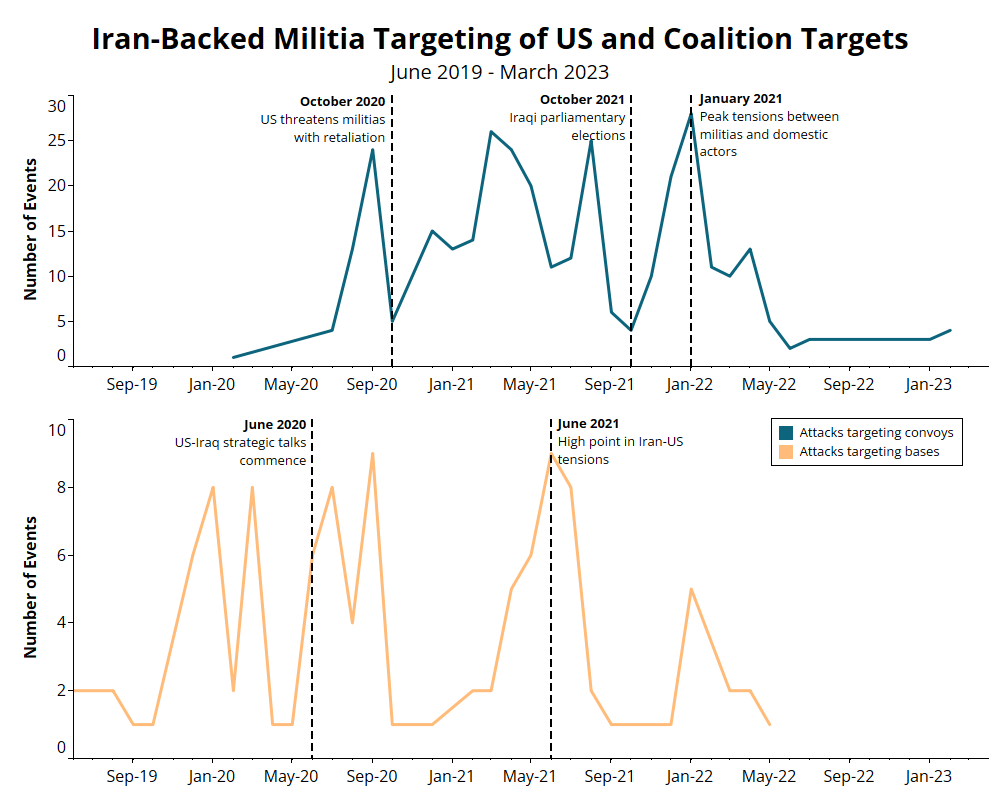

Since mid-2019, Iran-backed militias have strategically alternated the targeting of bases and convoys in response to three main factors: US-Iran tensions, intra-militia rivalry, and domestic political developments. These compounding factors contribute to defining three main phases in militia activity against US forces.

Phase 1: Heightened US-Iran tensions (June 2019-December 2020)

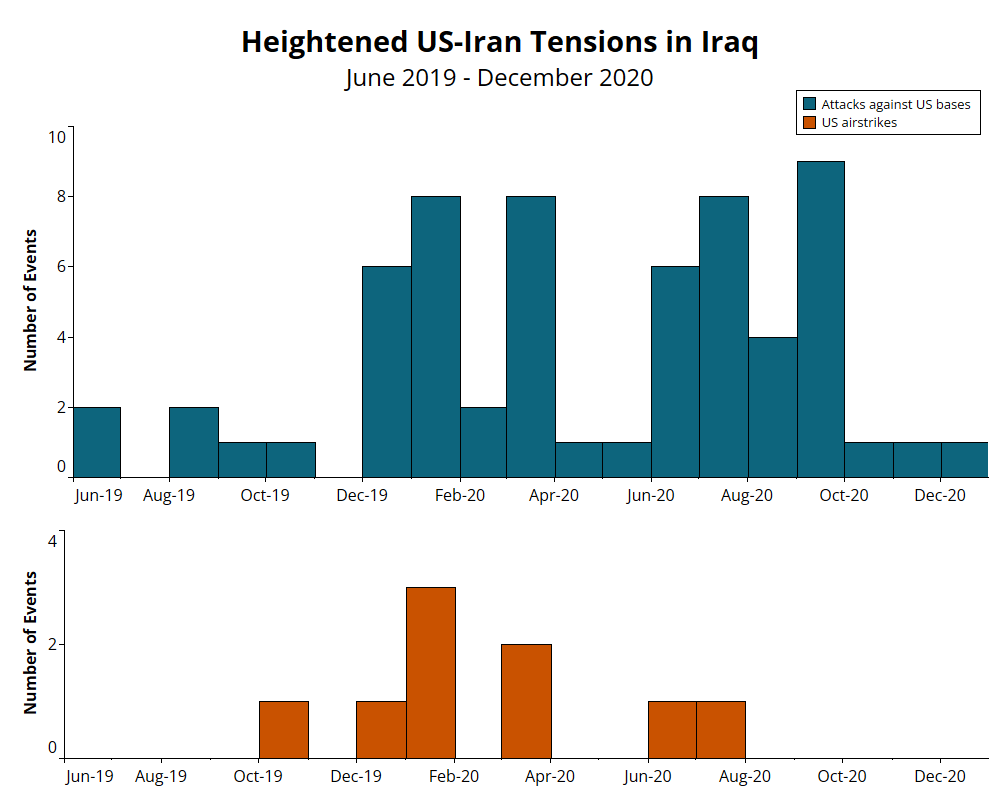

Tensions between the US and Iran loom large over the activity of Iran-backed militias in Iraq. In May 2018, the Trump administration suspended US participation in the Iran nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). Reacting to President Donald Trump’s “maximum pressure” policy of unilateral sanctions, Tehran began to break its JCPOA commitments in mid-20196‘The Failure of U.S. “Maximum Pressure” against Iran,’ International Crisis Group, 8 March 2021 and launched attacks on oil tankers in the Strait of Hormuz in June of that year.7Robert Burns and Lolita C. Baldor, ‘Trump blames Iran for tanker attacks but calls for talks,’ Military Times, 14 June 2019

Amidst these rising tensions, Iran-backed militias launched an unprecedented campaign of attacks against US targets that continued intermittently until September 2020. The US responded with a strategy of “contested deterrence,” limiting retaliatory strikes to major incidents involving US casualties (see graph below).8General Kenneth F. McKenzie Jr., ‘Marine Corps General Kenneth F. McKenzie Jr., Commander, U.S. Central Command Holds a Press Briefing on Defensive Strikes Against Iran,’ US Department of Defense, 13 March 2020 For instance, the US launched airstrikes on KH positions after KH attacks on the K-1 Coalition base in Kirkuk on 27 December that killed one US contractor and two policemen. A few days after, on 2 January 2020, the US also launched the airstrike that killed Soleimani and al-Muhandis in response to Iran-leaning demonstrators storming the US Embassy compound in Baghdad on 31 December 2020.9Al Jazeera, ‘Protesters storm US embassy compound in Baghdad,’ 31 December 2020

The latter incident had political and military consequences. On 5 January, the Iraqi parliament passed a non-binding resolution to “end the presence of any foreign troops on Iraqi soil and prohibit them from using its land, airspace, or water for any reason.”10Arwa Ibrahim, ‘Iraqi parliament calls for expulsion of foreign troops,’ Al Jazeera, 5 January 2020 Meanwhile, militias adopted two novel strategies to enhance plausible deniability and avoid US retaliatory strikes: first, they expanded the targets of their attacks to include convoys from February 2020 and more consistently since July; and second, by mid-March 2020 they started resorting to the use of facade groups. Facade groups emerged as ‘brands’ for specific types of attacks, with the aim of ‘muddying the waters’ and making it harder to trace attacks back to specific Iran-supported militias. The vast majority of facade groups appeared between March 2020 and March 2021, marketing themselves as vigilante or paramilitary actors.11Tamer Badawi, ‘Iraq’s Resurgent Paramilitaries,’ Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 22 April 2021

Militia operations against US bases and convoys escalated during the summer, pressuring the US to abandon smaller bases and outposts to avoid attacks on US soldiers,12Seth Frantzman, ‘How attacks on US forces in Iraq became a new normal,’ Atlantic Council, 28 August 2020 peaking in September 2020, while the US and the Iraqi government held talks over the presence of US troops in the country.13Mustafa Salim and Louisa Loveluck, ‘U.S. and Iraq begin talks on American troop presence as militant threat grows,’ The Washington Post, 11 June 2020 In 2020, ACLED records approximately 50 attacks on US bases – the highest number recorded in the country since the beginning of ACLED coverage in 2016.

Phase 2: Intra-militia rivalry, resumption of JCPOA talks, and increased convoy attacks (October 2020-September 2021)

In the lead-up to the US presidential elections in November 2020, Iran-backed militias declared a ‘conditional truce’ with US forces in Iraq on 10 October 2020, which suspended rocket attacks in return for a scheduled plan for US troops to leave the country.14Ali Mamouri, ‘US shakes up Iraqi factions with reported warning on militias,’ Al Monitor, 24 September 2020; Al Mayadeen, ‘The Iraqi resistance gives a conditional opportunity for foreign forces to leave the country,’ 10 October 2020 This truce lasted until 27 February 2021. Albeit sponsored by Tehran, the truce caused a fracture within the Muqawama. While KH-aligned actors redirected most of their activity against domestic targets (see inset box below) and US convoys, AAH-aligned actors refused to tow Iran’s line, continuing attacks on US bases. These high-profile attacks came amid widely held expectations that newly elected US President Joe Biden would rapidly withdraw American troops, allowing the AAH to portray itself as a defender of Iraq’s sovereignty that ‘forced’ the US out of the country.15Jacob Lees Weiss, ‘ Iran’s Resistance Axis Rattled by Divisions: Asaib Ahl al-Haq’s Leader Rejects the Ceasefire in Iraq,’ The Jamestown Foundation – Terrorism Monitor, 12 February 2021

This pattern of internal competition continued throughout 2021, with AAH shifting the focus of its operations towards convoy attacks, thus prompting an increase in an area of activity previously occupied by KH-aligned facade groups. ACLED records 180 events involving the targeting of US convoys in 2021, a threefold spike compared to the year prior. Around 40 of these incidents have been claimed by AAH-aligned facade groups, while KH-aligned groups claimed only 11. This figure is in line with reports suggesting that AAH-aligned groups took the lead in carrying out attacks against convoys, despite Iran’s instructions to de-escalate operations against US targets.16Michael Knights and Crispen Smith, ‘Ashab al-Kahf’s Takeover of the Convoy Strategy,’ The Washington Institute, 22 November 2021

During this phase, the pattern of militia attacks also evolved in response to the new approach taken by President Biden, who assumed office in January 2021. Biden endeavored to revive the JCPOA talks with Iran, de-escalate tensions in Iraq, and reduce US military presence in the Middle East more broadly. Meanwhile, Iran-backed militias maximized pressure by escalating convoy attacks and – in a further violation of the ongoing conditional ceasefire – an AAH facade group, Saraya Awliya al-Dam, claimed responsibility for an attack on a US airbase in Erbil on 15 February.17The attribution of the attack to Saraya Awliya al-Dam was disputed. Military expert Michael Knights suggested that another Iran-backed militia, Asaib Ahl al-Haq, could have been behind the attack. Bethan McKernan and Julian Borger, ‘Rocket attack on US airbase in Iraq kills civilian contractor,’ The Guardian, 16 February 2021. Notably, US forces avoided retaliation in Iraq, only responding 10 days later by targeting Iran-backed militias in eastern Syria,18Guita Aryan and Michael Lipin, ‘Iranian Proxy Attacks on Americans ‘Not Helping Climate in US’ for Reviving Iran Talks, US Envoy Says,’ VOA News, 18 March 2021 thus marking distance from Trump’s “contested deterrence” policy.

The JCPOA talks resumed in April 2021, with militia attacks against bases steadily increasing between April and June and remaining high throughout July. This spike in militia activity has several potential explanations. First, Iran-backed militias arguably escalated the attacks to pressure the US during the JCPOA talks. Second, contradictions inherent to the Biden administration’s policy towards Iraq, and the Middle East generally, emboldened militias to ramp up operations. Indeed, in April, the US defense secretary announced that there were no plans to withdraw US troops from Iraq,19Meghann Myers, ‘‘We’re going to stay in Iraq,’ says top US Middle East commander,’ Military Times, 22 april 2021 contradicting Biden’s electoral vow to “end the forever wars.”20Dan Lamothe, ‘Like Trump, Biden has promised to end the ‘forever wars.’ The landscape remains complicated,’ Washington Post, 9 December 2020 Lastly, in June, the US targeted KH-aligned groups in Syria in response to militia attacks in Iraq, with the Muqawama pledging retaliation.21The Iran Primer, ‘U.S. Strikes Iran-Backed Militias in Iraq, Syria,’ 9 July 2021

This impasse was eventually resolved in July when the US announced the end of the American combat mission in Iraq.22Kevin Liptak and Maegan Vazquez, ‘Biden announces end of combat mission in Iraq as he shifts US foreign policy focus,’ CNN, 26 July 2021 Following the announcement, attacks against US bases reduced to a trickle, completely ceasing before the Iraqi elections. Overall, ACLED records a 25% decrease in operations targeting US bases in 2021.

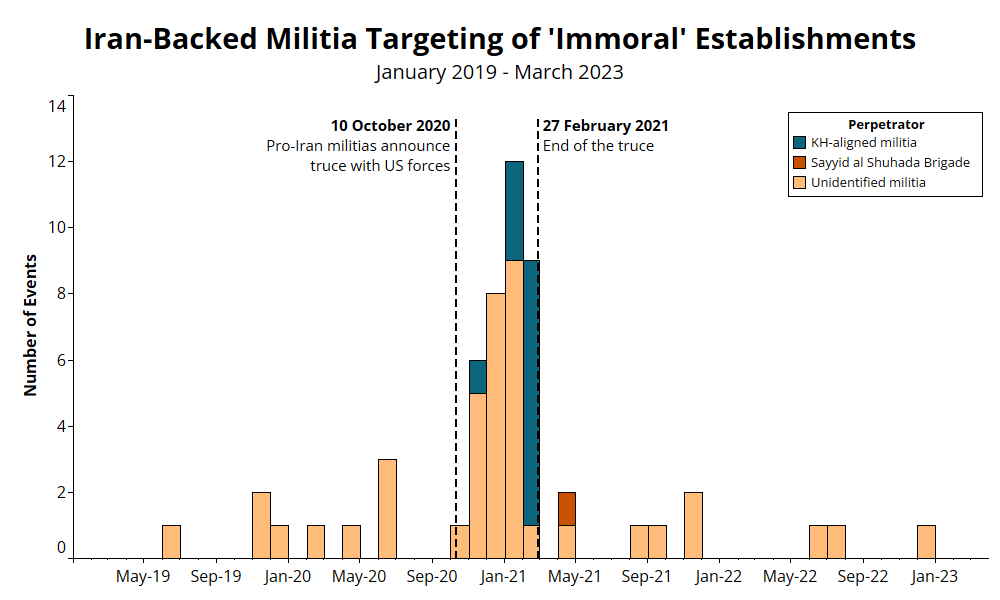

Rivalry Within the Iran-backed Network: The Targeting of Liquor Stores

Since the early 1990s, Muslim citizens have been banned from selling alcohol in Iraq. This has resulted in a de facto monopoly of alcohol sale for Christians and Yazidis23Independent, ‘Alcohol returns to Baghdad,’ 9 July 2008; Ali Mamouri, ‘’Iraq is not an Islamic country’: Minorities protest Baghdad’s alcohol ban as unconstitutional,’ Al-Monitor, 12 March 2023 that is concentrated around the Baghdad area, where Iran-backed militias protect the trade and exact fees.24Irfaa Sawtak, ‘Minorities are the first victims.. The sale of alcohol depends on the “consent of the militias”,’ 16 February 2022; Al Arab,‘The liquor trade in Iraq is a source of funding for the militias,’ 3 December 2020 Despite a 2016 law banning all alcohol sales,25Saad Salloum, ‘What’s really behind Iraq’s new alcohol ban?,’ Al-Monitor, 2 November 2016 the violent targeting of liquor stores remained at extremely low levels between 2017 and 2019, with an average of less than three events per year, according to ACLED data.

This pattern drastically changed during the ‘conditional truce’ announced by the Iran-backed militias. In October 2020, KH-aligned facade groups26Though most attacks remained unclaimed, all claimed ones involved KH-aligned facade groups, namely: Raba Allah, Ahl al-Qura, People of the Good, and Qasim al-Jabbarin. There are several elements suggesting that the unclaimed attacks were perpetrated by Iran-backed militias, including: their geographical distribution, mostly around Baghdad; the typology of violence, mostly consisting in non-lethal IED explosions aimed at causing material damage; and the timing, with the attacks escalating during the truce period. launched a campaign of attacks against providers of so-called ‘immoral’ services such as liquor stores, massage parlors, and nightclubs. Between October 2021 and February 2022, ACLED records over 35 ‘morality-driven’ attacks (see graph below), mostly involving the targeting of liquor stores with IEDs. Critically, these attacks completely ceased in the immediate aftermath of the truce in March 2021.

The KH-aligned facade groups involved in these attacks have been described as a sort of ‘morality police.’27Shafaq, ‘Raba Allah, a Shiite mutawwi or more?,’ 26 March 2021; Rudaw, ‘The People of the Good group warns against approaching liquor stores on New Year’s Eve,’ 27 December 2020 Yet the religious motive hardly explains the timing of the attacks. An alternative reading suggests these vigilante acts were triggered by intra-Muqawama competition. In fact, AAH illicitly exacted taxes from immoral establishments such as liquor stores and night clubs.28Michael Knights, Hamdi Malik, Crispin Smith, ‘Changing of the Guard: New Iraqi Militia Trends and Responses,’ The Washington Institute, 19 January 2021 By targeting alcohol sales, KH arguably affected one of AAH’s sources of revenue,29Nuha Mahmoud, ‘Iraqi militias build “an economic empire” from liquors,’ Sky News, 7 October 2018. thus effectively responding to AAH violations of the truce terms.

Phase 3: US withdrawal and a shift towards politics? (October 2021-present)

The Iraqi parliamentary elections on 10 October 2021 assigned the relative majority of seats to the party of the nominally anti-Iran cleric Muqtada al-Sadr, signaling a defeat for the Muqawama faction. Iran-backed groups rejected the electoral results, and commenced a new cycle of violence in November 2021 characterized by convoy attacks and an assassination attempt on Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi, all in an attempt to reverse their electoral defeat. This escalation continued until January 2022, when at least 28 attacks targeting convoys were reported, marking the highest monthly total recorded to date.

Meanwhile, the US and Iraqi governments agreed to end American combat roles in the country by 31 December 2021, reducing their presence to advisory and training functions.30US Department of State, ‘Joint Statement on the U.S.-Iraq Strategic Dialogue,’ 26 July 2021 As a consequence of this agreement, attacks targeting US and Coalition forces dropped precipitously in 2022. Attacks targeting bases and convoys decreased by 72% and 60%, respectively, over the year compared to the year prior, and ceased completely after August.

Intra-Shiite struggles over the election results dominated Iraqi politics for most of the first half of 2022.31John Davison and Haider Kadhim, ‘Deadly clashes rage in Baghdad in Shi’ite power struggle,’ Reuters, 29 August 2022; Martin Chulov, ‘Deadly violence in Baghdad after leading cleric Moqtada al-Sadr says he is quitting politics,’ The Guardian, 30 August 2022 This struggle reached a deadly peak in August 2022, when pro-Sadrist and pro-Coordination Framework (CF) forces – the political alliance that includes the militias – engaged in armed clashes in Baghdad. In the end, militia-backed and Iran-backed pro-CF forces emerged victorious over the Sadrists and formed the new Iraqi government.32Hassan Al-Saeed, ‘Militias protest after losses in Iraqi election,’ Al Monitor, 29 October 2021 For the rest of 2022, the goal of expelling US forces through armed engagement took a backseat while Iran-backed groups shifted their efforts to consolidate their political gains and reoriented their military activity against Turkish forces (see graph below).

Attacks Against Turkish Targets

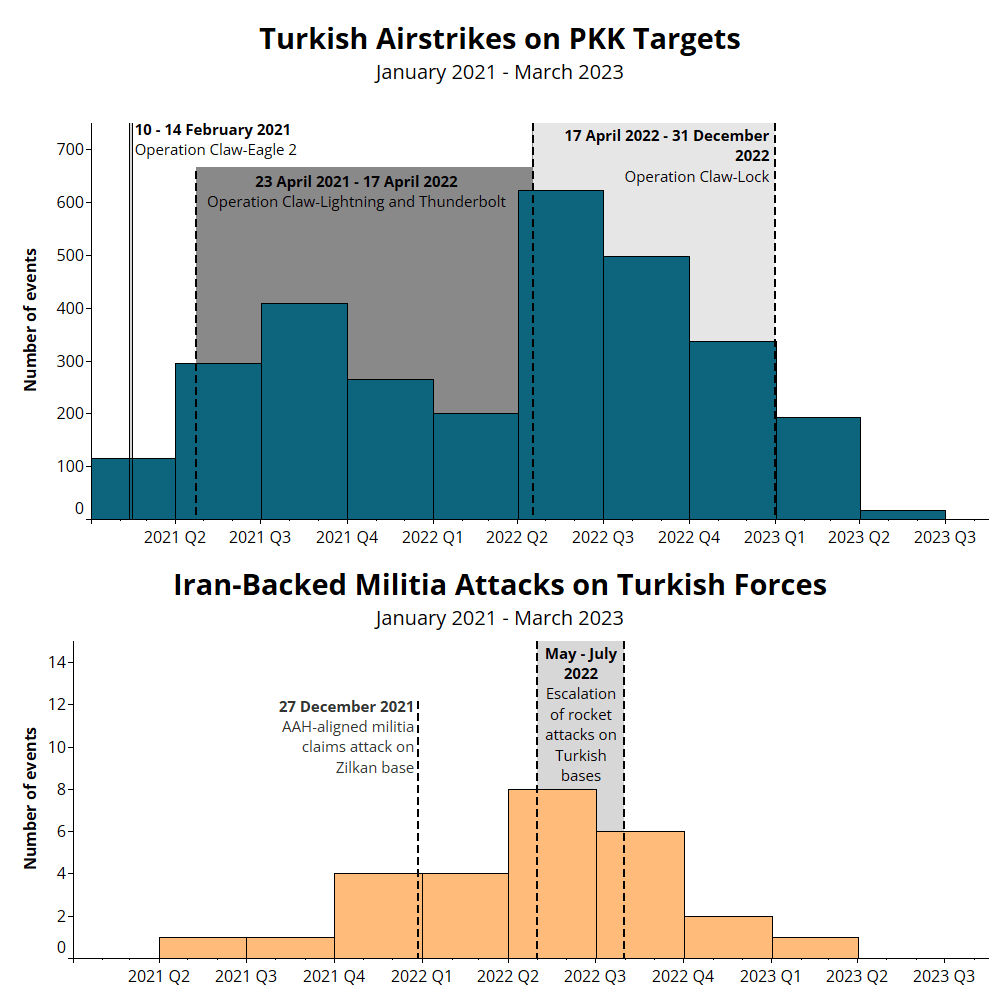

Between April 2021 and March 2023, ACLED records over 25 rocket and drone attacks against Turkish military bases, mostly aimed at Zilkan base in the northern governorate of Ninawa. Iran-backed militias publicly justify these attacks as a form of defense of Iraq’s sovereignty and opposition to foreign military presence. However, variations in this trend of militia activity seem to be underpinned by two underlying factors: the tactical alliance between Iran-backed militias and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK); and the degree of intensity of militia attacks against US forces.

In 2017, Iran-linked PMF units ousted Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) forces from Sinjar district,33Alia Chughtai, ‘Territory lost by Kurds in Iraq,’ 1 November 2017 entering a tactical alliance with the Sinjar Resistance Units (YBS) and the PKK.34International Crisis Group, ‘Iraq: Stabilising the Contested District of Sinjar,’ 31 May 2022 This move pitted Turkey – which backs the KRG and considers the PKK a “terrorist organization”35Republic of Türkiye, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ‘PKK’ – against the Iran-backed militias. Tensions further escalated in late 2020 into 2021: first, after the United Nations-mediated Sinjar agreement in October 2020 between the KRG and Iraq government mandated the withdrawal of the PKK and PMF units;36Shafaq News, ‘Text of Sinjar agreement,’ 10 October 2020 and early in the new year when Turkey launched a string of ground and air operations called Claw-Eagle 2, Claw-Lightning, and Thunderbolt targeting the PKK.37Al Jazeera, ‘Three Turkish soldiers killed in northern Iraq,’ 11 February 2021

Ankara’s operations against the PKK elicited the reaction of HHN and AAH, which threatened Turkey with military consequences in case of further escalation in Sinjar.38Dilara Aslan, ‘Turkey-Iran tensions on rise ahead of possible Sinjar operation, Daily Sabah,’ 7 March 2021 Yet, despite the high number of Turkish airstrike events recorded between April and October 2021, the militia reaction was low-level, with only two unclaimed rocket attack events targeting the Turkish Zilkan base in Bashiqa, northeast of Mosul, in April and September. Arguably, during this phase, militia resources were drained by their intensified attacks against US and Coalition forces.

However, starting from November 2021 – and coinciding with a drop in the number of attacks against US forces – Iran-backed militias escalated their attacks against Turkish bases (see graph below). The end of the Coalition mission in Iraq in December 202139Omar Sattar, ‘Combat mission of international coalition in Iraq has ended,’ Al Monitor, 3 January 2022 further refocused militia activity towards Turkey’s presence in northern Iraq, with AAH and KH publicly entering the ring of the anti-Turkey resistance. On 27 December, Liwa Ahrar al-Iraq – an AAH-aligned facade group40Hamdi Malik, Michael Knights, Eric Feely, ‘Profile: Liwa Ahrar al-Iraq,’ 29 July 2022 – attacked the Zilkan base with four separate rocket attacks. Meanwhile in February 2022, KH issued a statement threatening Ankara if it did not withdraw its troops.41Seth J. Frantzman, ‘Will Iranian-backed militias attack Turkey in Iraq? – analysis,’ 7 February 2022

In 2022, Iran-backed militias almost completely refocused their activity against Turkish forces, as reflected by a fourfold increase in militia attacks on Turkish positions. In April 2022, Ankara launched Operation Claw-Lock, causing a sruge in the number of airstrike events, which skyrocketed between May and July 2022. During the same quarter, Iran-backed militias escalated rocket attacks on Turkish bases, before continuing their attacks at lower levels until the end of the year. Around one-third of these attacks were claimed by Liwa Ahrar al-Iraq, followed by Ahrar Sinjar – a militia name reserved for anti-Turkey attacks linked to Yezidi grievances with Turkey. Overall, the use of facade groups as ‘brands’ for specific types of attacks, demonstrates the double aim of avoiding direct retaliation and maintaining plausible deniability.

Since the end of Operation Claw-Lock in December 2022, and in conjunction with the conflict’s annual winter lull, Ankara has steadily reduced military activities in northern Iraq. Furthermore, PKK militants announced a unilateral ceasefire in the wake of the earthquakes that struck Syria and Turkey on 6 February. Similarly, Iran-backed militias have almost completely stopped their attacks against Turkish positions in Iraq for the time being.

Looking Ahead: Resurgence of Militia Attacks on the Horizon?

Since mid-2019, the activity of Iran-backed militias has evolved under the influence of several factors: regional and domestic political developments, intra-militia competition, and variations in foreign presence inside Iraq. The bulk of militia operations remained focused on US targets, alternating attacks on bases and convoys to maximize pressure while avoiding retaliation. Yet, during ceasefires and increasingly after the drawdown of US forces in December 2021, militias have shifted their activity on other targets, namely ‘un-Islamic’ establishments and Turkish forces.

At present, the Iraqi political landscape is very favorable to Iran-backed groups. Albeit weakened by the 2021 elections, Iran-backed militias and their political arms gained unfettered access to state posts and institutions in 2022, after their rivals – the Sadrists – withdrew from Iraqi parliamentary politics in the aftermath of the August 2022 clashes in Baghdad.42Michael Knights, Hamdi Malik, and Crispin Smith, ‘The Muhandis Company: Iraq’s Khatam al-Anbia’, The Washington Institute, 21 March 2023 Furthermore, the ambivalent attitude of the Biden administration towards troop withdrawals from Iraq and the current lull in Turkish operations in the north have cleared two major hindrances to militia activities in the country.43Sean Mathews, ‘As Iraq’s political crisis deepens, US influence dwindles,’ Middle East Eye, 17 August 2022 Recently, militias have expanded their operations to target Kurdish oil installations, likely to pressure the KRG into taking pro-CF positions in federal politics,44Ans Azawi, ‘Kor Mor gas field attacked with rockets again… who is benefited?’ Al Hal Net, 26 July 2022 with at least nine rocket attacks against oil and gas fields in Erbil and Sulaymaniyah governorates reported since April 2022.

A resumption of major militia operations against foreign forces in Iraq remains a distinct possibility. Rising tensions in neighboring Syria between the US and Iran-backed militias connected to KH and AAH have already led to a deadly exchange of hostilities in March 2023.45The Guardian, ‘US strikes Iran-backed group in Syria after deadly attack on coalition base,’ 24 March 2023 Regional tensions between the US and Iran could possibly lead to low-level responses, such as the attacks against convoys recorded in 2023 after months of discontinuation. Still, how long this status quo will last in Iraq’s volatile politico-security landscape remains far from certain.

Visuals in this report were produced by Ana Marco