Regional Overview

Europe, Caucasus, and Central Asia

June 2024

Posted: 5 July 2024

In this Regional Overview

Armenia-Azerbaijan: Tensions on borders and streets persist

Azerbaijan resumed allegations of gunfire toward its positions following the demarcation of a section of its northwestern border with Armenia. Between 12 and 16 June, Azerbaijan claimed seven ceasefire violations, all in the direction of the Nakhchivan exclave. Previous escalations around the exclave occurred in summer 2021 and 2023, the latter in the run-up to Azerbaijan’s takeover of Artsakh. Additionally, Azerbaijan claimed two instances of Armenian fire in the direction of its positions in Kalbajar region on its western border. Armenia refuted all claims and proposed to set up a joint body tasked with investigating alleged breaches of ceasefire.1Arshaluys Barseghyan, ‘Armenia floats ceasefire monitoring mechanism as Azerbaijan continues accusations,’ Open Caucasus Media, 24 June 2024 The sides exchanged peace treaty proposals, with Azerbaijan continuing to demand changes to Armenia’s constitution, which makes references to Artsakh.2The disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh is internationally recognized as part of Azerbaijan. ACLED refers to the former de facto state and its defunct institutions in the hitherto ethnic Armenian majority areas of Nagorno-Karabakh as Artsakh — the name by which the de facto territory used to refer to itself. For more on methodology and coding decisions around de facto states, see this methodology primer. Armenia reiterated its willingness to conclude the treaty as soon as possible while striking a deal to procure French artillery.3Euractiv, ‘Armenia, Azerbaijan trade barbs after France pledges CAESAR howitzers to Yerevan,’ 20 June 2024

Meanwhile, the number of demonstrations in Armenia against the handover of four border villages to Azerbaijan declined significantly. ACLED records a 70% decrease in related demonstrations compared with the average in April and May. However, one spate of demonstrations occurred in mid-June, led by Bagrat Galstanyan — a Tavush cleric currently running for prime minister. On 9 June, 15,000 demonstrators rallied and set up a tent camp in the capital city, Yerevan, demanding that Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan resign within 96 hours.4Arshaluys Barseghyan, ‘Armenian anti-government movement issues 96-hour ultimatum,’ Open Caucasus Media, 10 June 2024 On 12 June, the demonstrators closed in on the parliament building, where Pashinyan was holding a Q&A session. Police responded with stun grenades; as a result, over 100 people, including 18 police officers, were injured.5Arshaluys Barseghyan, ‘Over 100 injured after police deploy stun grenades against Yerevan protesters,’ Open Caucasus Media, 13 June 2024 Subsequently, Galstanyan’s supporters dismantled the tent camp as the opposition failed to secure a no-confidence vote.6Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty – Armenian Service, ‘Outspoken Armenian Archbishop Leads Another Anti-Government Rally In Yerevan,’ 17 June 2024 Sporadic protests by Galstanyan’s supporters continued until the end of June, mostly in Yerevan.

France: Far-right electoral gains prompt protests and attacks

On 9 June, the far-right National Rally party won 30 of 81 seats allocated for France in the European Parliament. In response to the results, President Emmanuel Macron dissolved the National Assembly and called early legislative elections for 30 June with a runoff on 7 July. The unprecedented National Rally gains and the prospect of a far-right majority in the upcoming parliament prompted demonstrations across France against the far-right and racism. On 15 June, thousands of people took to the streets in at least 140 distinct locations across the country, joining rallies called by trade unions and left-wing groups and demanding that the latter join forces in a newly created leftist electoral bloc.7CGT, ‘Après le choc des européennes les exigences sociales doivent être entendues !,’ 11 June 2024; Abel Mestre, ‘Mobilisation contre l’extrême droite : à la recherche de l’esprit du 21 avril 2002,’ Le Monde, 29 June 2024 The gatherings were for the most part peaceful, though some public property damage and scuffles with police occurred in major cities.

Meanwhile, the National Rally’s score in European elections may have emboldened far-right radicals to engage in street violence. On the night following the election, four members of the now-banned Groupe Union Défense (GUD)8Le Monde, ‘Le GUD est officiellement dissous, annonce le gouvernement,’ 26 June 2024 — a neo-Nazi student movement — roamed the streets of Paris armed with belts and sticks. They beat up a queer person, fracturing their brow bone. ACLED records at least three other attacks by far-right groups in June, including in Angers, Montpellier, and Lyon. Separately, on 20 June 2024, in Saint-Etienne near Lyon, a group of hooded people attacked four National Rally activists, including one parliamentary candidate, who sustained injuries and was taken to a hospital.

See also ACLED Brief Is radical group violence on the rise in the EU?

Russia: Dagestan suffers its worst Islamist attack in a decade

On the evening of 23 June, five suspected Islamist militants attacked Orthodox churches, synagogues, and police outposts in and between Derbent and Makhachkala, in Russia’s North Caucasus republic of Dagestan. The perpetrators killed at least two civilians, including an ailing priest in Derbent, and burned down a synagogue in Makhachkala. Over 15 officers were killed in the subsequent shootouts. All perpetrators, including two sons of a local official who was subsequently arrested, were shot dead as well. In response to the attack, authorities in Dagestan are vetting local administrators for links with Islamist militants9Andrew Osborn, ‘Dagestan political elite to be vetted for links to radical Islam after shootings,’ Reuters, 25 June 2024 and raiding local martial arts clubs believed to be linked to the perpetrators.10Nicole Wolkov et al., ‘Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment,’ Institute for the Study of War, 2 July 2024 None of the Islamic militant groups active in Russia claimed responsibility for the attacks, which came three months after the Islamic State Khorasan Province attack on a concert hall in Moscow in March. The impoverished Muslim-majority republic had been spared acute violence in the past decade11Katie Marie Davies, Dagestan, in southern Russia, has a history of violence. Why does it keep happening?’ Associated Press, 24 June 2024 but remained vulnerable to extremist agitation. For instance, at the onset of the war in Gaza in October 2023, mobs stormed a hotel and an airport in Dagestan looking for Jewish people rumored to be arriving from Israel. Earlier in June, six pre-trial inmates suspected of affiliation with the Islamic State were killed after taking two prison guards hostage.

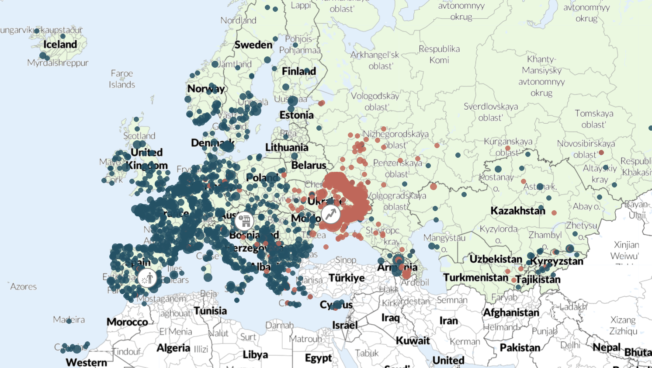

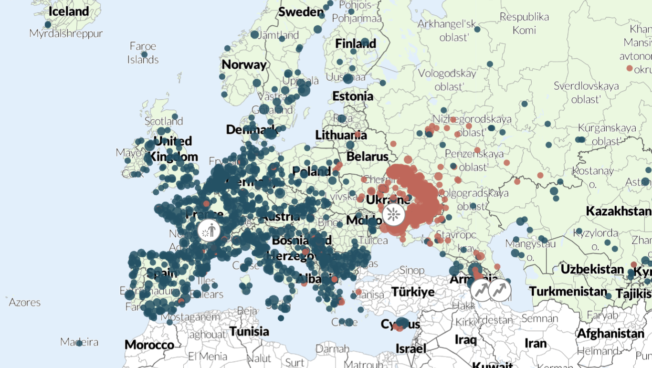

Russia: War spillover reaches an all-time high

Cross-border drone strikes nearly doubled in June compared with May. ACLED records more than 900 such strikes — an all-time high since May 2023 when Russia’s border regions began the target of cross-border attacks from Ukraine. Although Belgorod region was the target of close to 80% of drone attacks in June, over 150 were directed at Kursk region, nearly doubling the number of such attacks in May, which had already seen a significant increase. Russia’s oil processing and storage facilities remained the preferred target. Russian emergency services struggled to put out a fire at a fuel facility near Azov in Rostov region for several days after a drone strike on 18 June.

Ukrainian forces also expanded the air campaign to Russia’s military facilities on the other side of the border and deep inland, with command posts, air defense installations, and combat aircraft facing a particular threat. One of the largest drone barrages on 21 June targeted a Russian military airbase near the town of Yeisk in Krasnodar region, allegedly striking a drone storage and command point. In addition, Russian forces shot down their own military helicopter while fending off the attack. Against the background of escalating cross-border violence, Russia concluded a mutual defense pact with North Korea, which is reported to have already supplied about 1.6 million artillery shells — thus helping Russia turn the tide in its war against Ukraine.12Joyce Sohyun Lee and Michelle Ye Hee Lee, ‘Russia and North Korea’s military deal formalizes a bustling arms trade,’ Washington Post, 22 June 2024

Ukraine: Russia presses ahead while targeting the power supply

With the number of clashes remaining as high as in May, Ukrainian forces slowed Russia’s advance. In the northern Kharkiv region, Russian troops became bogged down in urban fighting in the border town of Vovchansk after reinvading the area. The relentless aerial bombardment of Kharkiv city and its environs continued. In the Donetsk region, Russian forces also stalled at the key strategic town of Chasiv Yar to the west of Russian-occupied Bakhmut, despite securing a southeastern suburb and attempting to circumvent the defenders from the north. However, they expanded their bridgehead northwest of Avdiivka in the area of Ocheretyne and launched assaults on pockets of the frontline near Siversk and Toretsk. The fighting prompted the evacuation of remaining civilians from Toretsk.

Unable to break through the frontline, Russia continued its targeting of energy infrastructure in Ukraine’s hinterlands. A barrage of missiles and drones on 1 June hit not only power plants but also gas transmission and storage infrastructure in western Ukraine. The strikes also targeted the Dniprovska hydroelectric power plant in the Zaporizhia region, which Russian missiles had already rendered inoperational in March.13The New Voice of Ukraine, ‘Kyiv likely to face up to 8-hour power outages, energy expert warns,’ 3 June 2024 This aerial offensive on energy infrastructure is estimated to have knocked out more than half of Ukraine’s power generation, including about 80% of the country’s thermal power capacity.14Sam Cranny-Evans, ‘Bracing for the Hardest Winter: Protecting Ukraine’s Energy Infrastructure,’ Royal United Services Institute, 24 June 2024

For more information, see the ACLED Ukraine Conflict Monitor.

See More

See the Codebook and the User Guide for an overview of ACLED’s core methodology. For additional documentation, check the Knowledge Base. Region-specific methodology briefs can be accessed below.

Links:

For additional resources and in-depth updates on the conflict in Ukraine, check our dedicated Ukraine Confict Monitor.