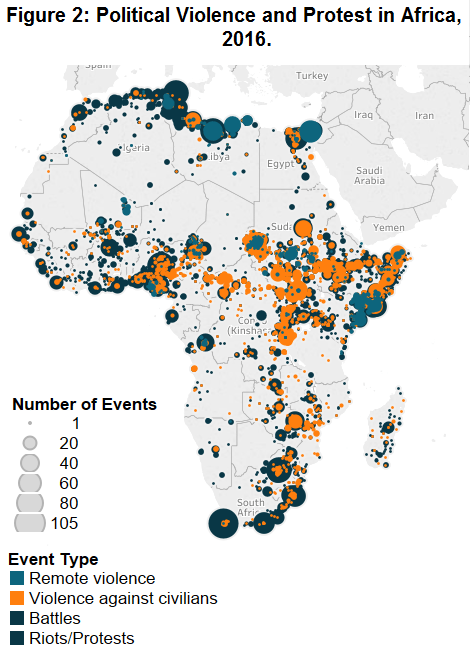

African states experienced high rates of both political violence and protest in 2016 (see Figure 2). The aggregated totals are remarkably similar to those of 2015, which indicates three important lessons going forward:

African states experienced high rates of both political violence and protest in 2016 (see Figure 2). The aggregated totals are remarkably similar to those of 2015, which indicates three important lessons going forward:

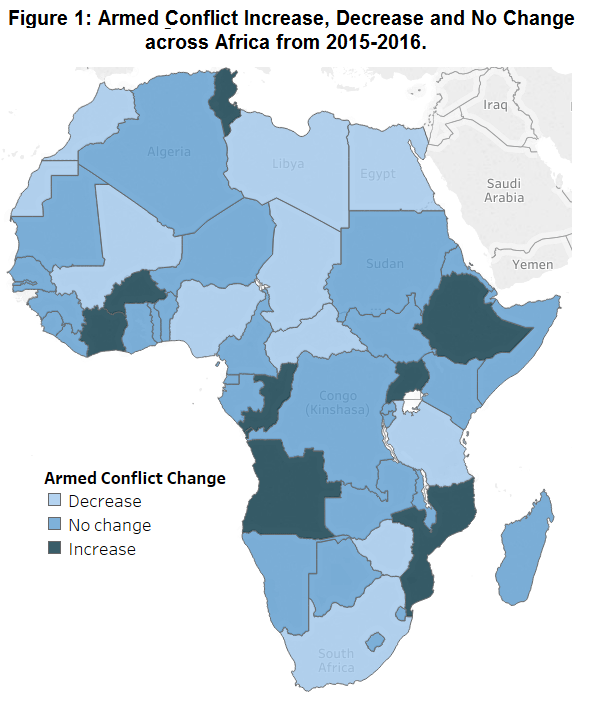

The crisis points on the continent- Libya, South Sudan, Somalia, and Nigeria- continue to produce significant violence, with substantial harm to civilians and the political process of peace. But under-reported crises constitute a large proportion of violence across African states, including the ‘not quite civil war’ in Burundi, and the ongoing wars occurring in Sudan, Ethiopia’s protests and conflict, and the increasing violence activity throughout Mozambique. Finally, the continent contains a multitude of different means to oppose, challenge and enforce governments and government policy, and a ‘one size fits all’ approach to analysis will produce poor results.

But the overall patterns are clear: battles and large scale wars are on the decline, as they have been for quite some time. In their place are multiple, co-existing agents who engage in a variety of strategies to make their place within the political landscape: local militias, pro-government militias, political militias working at the behest of politicians and political parties, civil society organizations forming protest movements, external groups seeking local partners (e.g. ISIS), and more occasionally, rebel groups seeking to overtake the government. These groups may use similar forms of violence — including attacking civilians, bombing, clashing with security forces, rioting — but they are distinct in their goals. Their separate and combined effect on life across Africa is distinguished by the levels and periods of violence they produce.

The conflicts affecting African states are not unique, and their experiences are instructive to the rest of the world: in a time when pitched battles decrease, a rise in overall insecurity is gripping developing and developed states. Across Africa, governments and citizens have lived in states of disorder that reflect the political dynamics of the moment. State governments are forcefully demonstrating their hold of the means of violence within and across borders, and actions that involve state forces continue to rise —24% of all actions in 2016 involved state forces, a proportion close to other recent high points of 2011-2012. When combined with the acts of militia groups who are often producing violence at the behest of powerful local, regional or party political leaders, the conclusion is that politics is causing political violence, and the strongest are using violence to enforce their will on others.

The events across the combined large-scale crises in Africa include Libya, Somalia, South Sudan and Nigeria comprise 33% of all violent conflict that occurred across Africa in 2016; this total represents a decrease from 35% in 2015, and 40% in 2014. But 55% of all fatalities attributed to political violence occur in these states, down from 58% in 2015. There are significant differences between the overall conflict profile of the continent, and the combined conflict patterns across these crises: there are far more clashes with security forces and other armed agents at 45% of the total activity (compared to a 30% continental average), and attacks on civilians are similar, but fatality risks are 5% higher than in non-crisis areas. These totals suggest that the likelihood of experiencing a pitched battle are significantly higher in crisis areas, but violence against civilians is more widespread across the continent.

Of those crises, Somalia remains the most active, followed by Nigeria, South Sudan and Libya, respectively. Somalia has almost three times the violence of the other states, who each have approximately 740 armed, organized events in 2016. In effect, Somalia’s violence is equal to the combined violence of Libya, South Sudan and Nigeria. Yet the fatality ratios suggest a different story: while Somalia has the highest total number of reported fatalities, Nigeria has the highest ratio at over 6 fatalities per event, compared to 2.5 per event in Somalia, 4.5 for South Sudan and close to 4 per event in Libya. Other striking differences underscore how these crises are distinct: fatalities in Nigeria are overwhelmingly against civilians compared to battles between armed agents, and fatalities when the state retakes territory are also markedly higher than in other crisis contexts. Libyan conflict appears to avoid direct targeting of civilians.

The heterogeneity of agents is an important indicator of how manageable a crisis is, as a low number of actors means that parties can coordinate to end violence and cooperate in a transformed political system. Unfortunately, the four crisis states suggest a very diverse environment: Libya’s distinct armed, organized agent total in 2016 is 66, more than double the number in 2012-2013. Despite Nigeria’s decreasing violence, the number of violent agents has increased from 53 to 93; yet both Somalia’s agents (156) and South Sudan’s (69) have decreased in small numbers from last year. The increase in Nigeria is entirely attributed to communal, local groups; typically increases in such groups suggest that sectarian violence is increasing as ‘identity politics’ resumes a primary divider of communities; and also confirms that law enforcement and trust in security forces is low at the local level. Groups that take violence into their own hands to address local political issues bypass the state and state laws to do so, often without recourse from the government. In particular, the Nigerian state has been active in other realms, which may suggest another reason why local groups are using an ‘unsupervised’ moment to engage in violence, or taking advantage of other internal crises to resume and reframe long running local conflicts. These small groups — across Nigeria and Somalia primarily — frequently appear but do not persistently engage in conflict; instead small flare ups are common. However, campaigns like the Fulani in the Middle Belt of Nigeria surpass a local skirmish and indicate far wider problems for governance and rule of law in the region.

There are few indications that the violence in these four countries will decline in 2017 — barring Libya’s minor decrease, all have sustained similar levels or grown, in Somalia’s case. But they represent very different conflict forms, and the intensity and form of their violence cannot be overstated. Somalia is now well into a competition between the government and a revived Al Shabaab; unwelcome new members — including ISIS — make headline news, but the majority of violence continues to be due to Al Shabaab’s attempts to dismantle any sign of functioning central or regional governance. Over a hundred small clan groups create local violence that has long substituted for a security system. Libya is torn between three governments with unequal legitimacy and capacity; Nigeria has successfully stopped Boko Haram’s domestic advances, but the group remains, along with a host of additional security vacuums that emerged during the Jonathan Presidency. Finally, the South Sudan war persists and diffuses (in all likelihood, southward in 2017), with no end to the destruction in sight, and no capable political leader on the horizon.

Underreported Conflict and Riots/Protests

Political violence is not limited to countries experiencing civil wars or large-scale insurgencies. Despite lesser media coverage, a number of countries across the continent witnessed lower yet sustained rates of armed conflict, as state and non-state actors continue to use violence to influence political dynamics or consolidate their position vis à vis other competitors. The political nature of these low-level conflicts is such that, unless a political solution to the crises is found, violence is likely to persist or to escalate in the near future. This situation is common in several African states, but particularly intense in Burundi and Mozambique.

In Burundi, battles between armed groups declined markedly in 2016 compared to the previous year (ACLED, May 2016). This pattern suggests that rebel groups have largely renounced armed confrontations with state forces as the government managed to retain control of its territory. However, data show a sustained increase in civilian targeting, reflecting the changing nature of the Burundi crisis and its persistent lethality. Rather than seeking direct confrontation, government forces and armed militias widely resorted to violence against unarmed civilians and targeted political assassinations to either consolidate the grip on power or manifest their strength. While the government has been successful in fending off the insurgency started in 2015, this has not stopped the violence, which will likely continue to affect the country in the coming months.

A low-level armed conflict also continued to endanger the fragile peace between ruling FRELIMO and the former rebels of RENAMO in Mozambique (ACLED, 7 October 2016; ACLED, 8 April 2016). Intermittent truces between the two parties have failed to stop the violence, which has increased from 19 conflict events in 2015 to 92 in 2016. The largest increase involved violence against civilians, which constitute the vast majority of events and are the largest contributor to conflict-related fatalities. The two parties, who accuse each other of violating short-lived ceasefires, are battling over the control of profitable trade routes and local governance in the northern RENAMO strongholds. Despite their mutual commitment to resuming the peace process, these trends suggest that both FRELIMO and RENAMO target non-combatants in the attempt of enhancing their bargaining position.

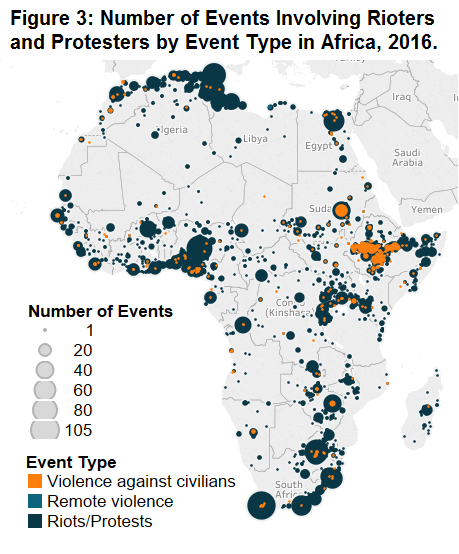

Opposition to governments across Africa has also taken different forms, as several African states continued to witness high rates of protest activity (see Figure 3). The number of events involving protesters and rioters increased by 4.8% from 2015, with major increases recorded in Ethiopia, Chad and Tunisia. South Africa and Ethiopia make up approximately one third of total protest events, with this share increasing to 50% when including Tunisia and Nigeria.

The poor performance of governments was the most common driver of protest, with citizens all across the continent demonstrating against ailing service delivery, deteriorating socioeconomic conditions and increasing physical insecurity. In many countries, protests were linked to the election cycle, to contest or influence the outcome of the vote – as in Gabon or Uganda – or to demand new elections – as in the case of the postponed elections in Democratic Republic of Congo. A third common motive of protest was the absence of political liberties and government repression, which sparked most protest events in Ethiopia and Chad.

These trends reveal that popular protests present a serious challenge for the stability of African governments. Protests are not only widespread within and across states, but in some cases – the most notable being the Arab uprisings in 2011 – they have proved successful in bringing about far-reaching political changes. As such, both democratic and (semi-)authoritarian governments have developed a variety of strategies to cope with dissent, ranging from tolerance and accommodation – as during the recent wave of protest in Morocco – to outright repression – as in Ethiopia and Sudan.

An overview of regions shows the multifaceted geography of riots and protests across the continent. In North Africa, all states witnessed high rates of protest activity in 2016, confirming the longer trend started in 2011. In Algeria and Tunisia, the number of protest events was higher than in 2011, raising concerns that local grievances may give rise again to wider collective actions. Despite a relative decrease from the previous year, protest movements in Egypt, Morocco and Libya have also called attention to the multiple weaknesses of these states.

South Africa experienced the highest level of protests and rioting in 2016. Violent riots marred the run-up to the municipal elections in August and the student-led #FeesMustFall campaign, revealing widespread dissatisfaction with the policies of the African National Congress (ACLED, 9 December 2016). Police often resorted to violent means in the attempt of curbing protests, but this repression ended up feeding more disorder. With new general elections scheduled in 2019 and growing infighting within the ruling party, violence is likely to feature prominently over the coming months in South Africa.

Despite the frequent use of violence by both protesters and police, protest activity has largely remained peaceful in South Africa. By contrast, the greatest share of violently repressed protests was found in Ethiopia, where security forces reportedly killed 486 protesters and hundreds of other civilians as a wave of popular mobilisation spread across the country (Insight on Conflict, 2 November 2016). While it is unclear if the state repression has been successful in stifling dissent or inhibiting media reporting, the new year may tell if the government will face an insurgency or alternative forms of mobilisation arising from the ashes of the Oromo protest movement.

Conflict Agents

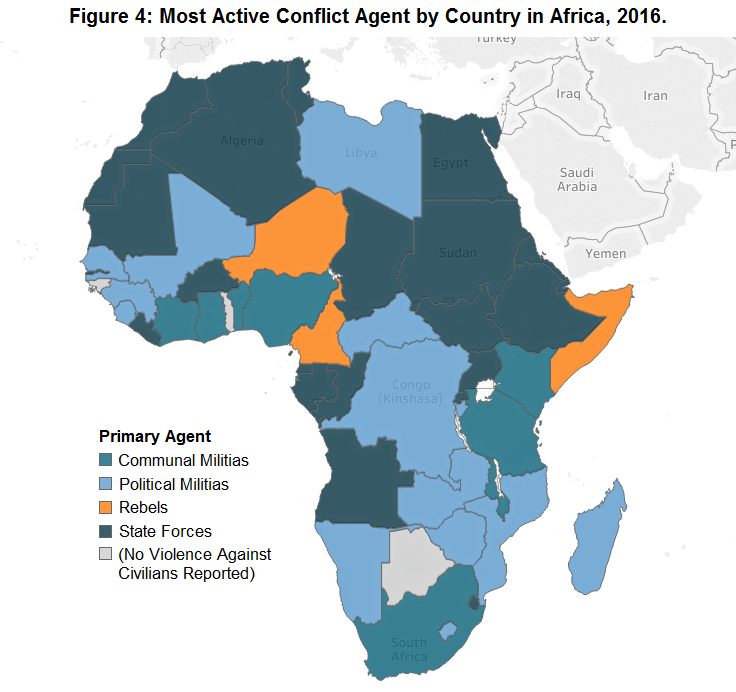

In the past two decades, the primary perpetrators of organized, armed political violence on the African continent changed from rebel groups to political militias (see Raleigh, 2014) and government forces. Figure 4 maps the most active agent in each African country in 2016. In the majority of countries, either state forces or political militias are the most active agent in conflict.

In 2016, political militias were responsible for 30% of all organized armed conflict in Africa. These groups use violence as a means to shape and influence the existing political system, but do not seek to overthrow national regimes. They instead operate as ‘armed gangs’ for different political elites – including politicians, governments, opposition groups, etc. Of named political militias, the Imbonerakure of Burundi (the militant youth wing of the CNDD-FDD) was by far the most active, whose involvement nearly doubled from 138 conflict events in 2015 to 202 conflict events in 2016 in conjunction with the Burundi Crisis.¹

Government forces are responsible for 34% of all conflict in Africa during 2016. This is an increase in their rate of involvement for the second year in a row as they seek to forcefully demonstrate their hold of the means of violence within and across borders. Government forces are the only group to have increased their rate of involvement in conflict from 2015 to 2016 (from 31.7% to 33.7%). The most active state forces in 2016 are the militaries of Somalia, Sudan, Ethiopia, and South Sudan – with especially stark increases in the rate of activity of the militaries of Sudan from 332 to 460 events between 2015 and 2016; and Ethiopia, whose involvement nearly tripled from 155 conflict events in 2015 to 448 in 2016. Conflict spiked in Sudan in the first half of the year, primarily driven by battles opposing government and rebel forces, which reached their highest levels since 1997. These clashes have occurred against a backdrop of limited advances on the political stage, with ceasefires proving difficult to hold as a result. The increase in state conflict involvement in Ethiopia in 2016 is driven almost entirely by the uprisings in the Oromia region, where in its strenuous efforts to contain a wave of protest unseen for decades, the government has launched a violent crackdown that is estimated to have killed more than one thousand people over one year.

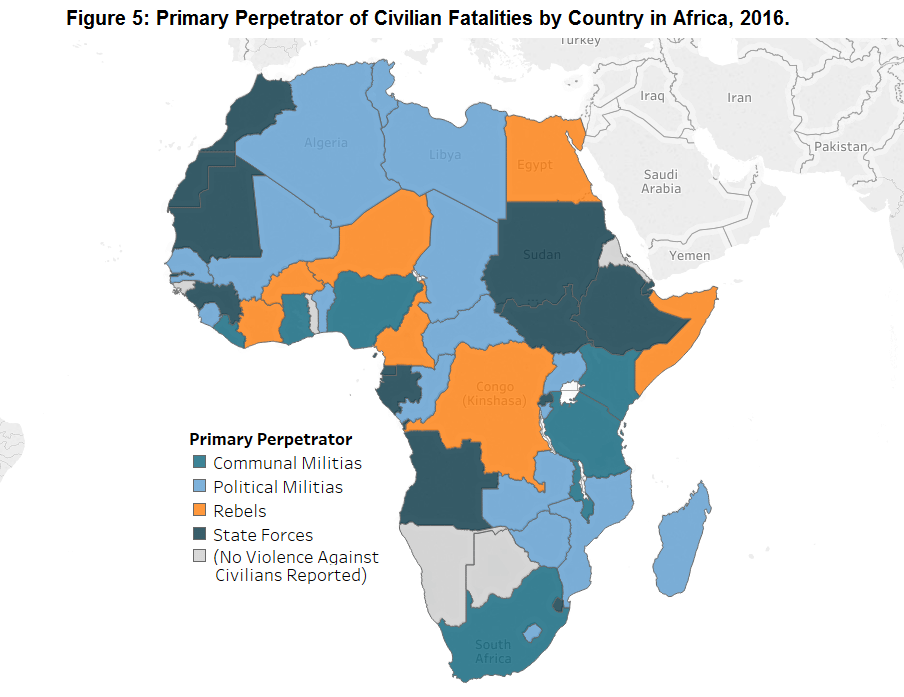

Political militias, government forces, and communal militias are the primary perpetrators responsible for reported civilian fatalities across the African continent; all three of these groups increased their rate of civilian fatalities from 2015 to 2016. Figure 5 maps the most lethal agents of civilian targeting in each African country in 2016.

Increases in reported civilian fatalities at the hands of communal militias is largely driven by the lethality of the Fulani ethnic militia in Nigeria, which is responsible for a reported 884 civilian fatalities in 2016 (up from 546 in 2015), as well as the Murle ethnic militia in Sudan, whose targeting multiplied over six times (responsible for 246 reported civilian fatalities in 2016). The increase in the rate of involvement in violence against civilians by state forces is largely driven by the military forces of Ethiopia, in conjunction with the uprisings in the Oromia region, and Sudan with the increase in violence combatting opposition. Unidentified armed groups (UAGs) continue to be lead perpetrators of civilian targeting, often used because of their anonymous status; UAGs in Burundi, Nigeria, South Sudan, Somalia, and Sudan continue to be highly active and lethal. (For more on the strategic use of UAGs in conflict zones, see the ACLED blog post on the topic.)

Rebel group presence continues to be lethal for civilians, these groups are responsible for a reported 1,684 civilian fatalities in 2016, but this represents a dramatic decrease from a reported 7,285 civilian fatalities by rebels in 2015. This decrease is largely a result of the decrease in reported civilian deaths at the hands of Boko Haram (Wilayat Gharb Ifriqiyah) – which is in large part due to a loss of territorial control following large-scale military operations in Yobi, Borno and Adamawa State. Regardless of this decrease, however, Boko Haram remains one of the top three largest threats to civilians in Africa – responsible for 790 reported civilian fatalities in 2016.

_______________________________________________

¹ACLED classifies unidentified armed groups (UAGs) with the same interaction code as political militias as these groups have many similarities to political militias, especially in that they can often act as ‘mercenaries’ and do the violent bidding of elites. These political elites (governors, political party leaders, etc.) are similar to governments in that they do not want to take open responsibility for their violent actions by name. Unidentified armed groups (UAGs) constitute a large share of violent actors in the ACLED dataset; nearly 20% of organized armed conflict carried out by violent actors last year in Africa involve UAGs.

This report was originally featured in the February ACLED Africa Conflict Trends Report.

Authors: Professor Clionadh Raleigh, Andrea Carboni and Dr Roudabeh Kishi.