10 Conflicts to Worry About in 2022

Myanmar

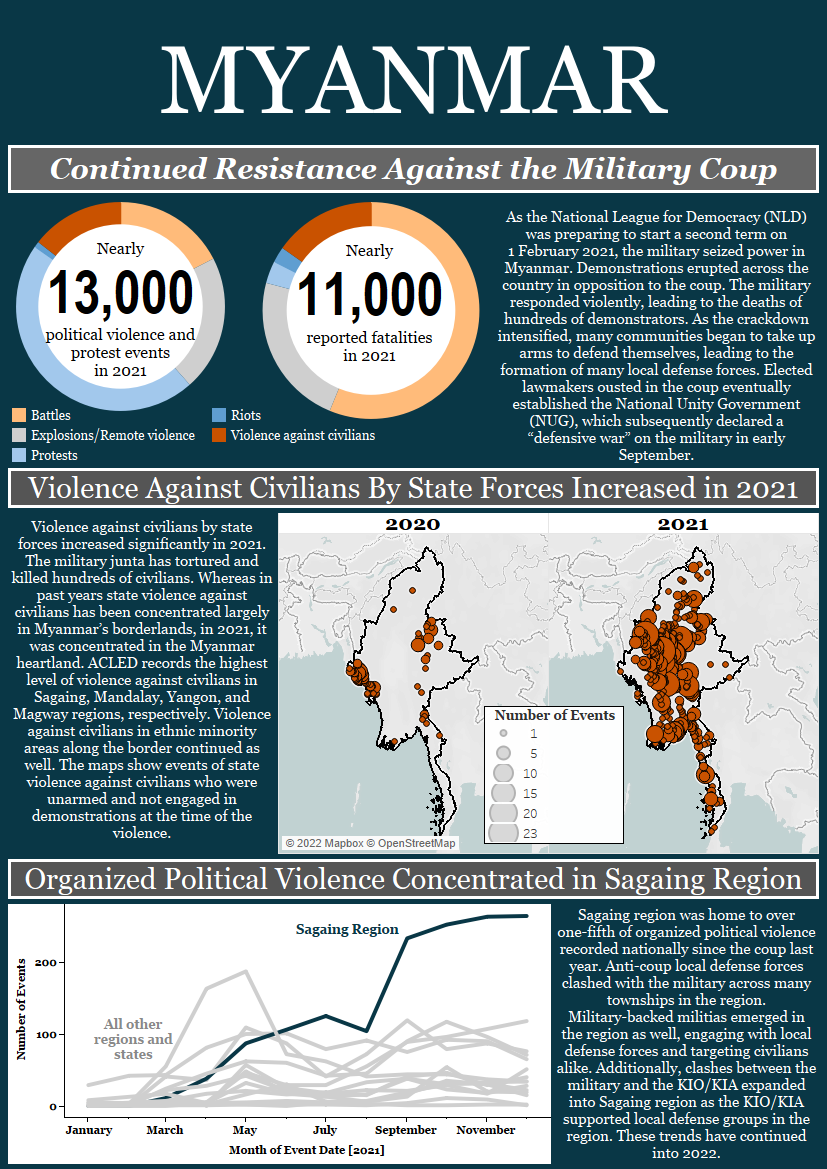

Continued resistance against the military coup

As the National League for Democracy (NLD) was preparing to start a second term on 1 February 2021, the military seized power in Myanmar. Demonstrations erupted across the country in opposition to the coup. The military responded violently, leading to the deaths of hundreds of demonstrators. As the crackdown intensified, many communities began to take up arms to defend themselves, leading to the formation of local defense forces. Elected lawmakers ousted in the coup eventually established the National Unity Government (NUG), which subsequently declared a “defensive war” on the military in early September (Guardian, 7 September 2021).

Demonstrations in opposition to the military coup in 2021 were large-scale and widespread. ACLED records over 6,000 anti-coup demonstration events throughout the year.1ACLED is currently supplementing its coverage by coding additional sources for 2021. It is expected that this number will thus increase when this project is completed. While the demonstrations remained largely peaceful, the military frequently responded with deadly violence, in many cases firing live rounds at demonstrators’ heads (Human Rights Watch, 2 December 2021). Women have played a key role in the movement (Al Jazeera, 25 April 2021), often standing on the front lines at demonstrations (Time, 31 May 2021); in turn, they have been met with targeted violence (GIWPS, 28 January 2022). According to ACLED data, Myanmar was the deadliest country in the world for demonstrators in 2021 (for more, see ACLED’s infographic: Deadly Demonstrations). Despite the crackdown, demonstrations have continued, often taking the form of flash-mob style events.

The degree of violence against civilians by state forces since the coup has been particularly severe, with a 620% increase in such events recorded in 2021 compared to 2020. Multiple cases of civilians being burned to death have been reported (Myanmar Now, 14 December 2021). On 24 December, for example, more than 30 people, including two aid workers, were burned to death by the military in Hpruso township in Kayah state. Earlier in December, in Done Taw village in Sagaing region, 11 villagers were burned to death by the military. As well, amid mass arrests of people accused of expressing opposition to the coup, the military has tortured detainees and committed acts of sexual violence against women and men (Myanmar Now, 3 January 2021).

Hundreds of local defense forces have emerged across the country in response to the ongoing military violence. Several groups were formed independently of the People’s Defense Force (PDF) under the NUG. However, the NUG has moved to consolidate the activity of local defense groups under a central command structure (Irrawaddy, 29 October 2021). Local defense groups have aimed to make the country ungovernable by the military junta. In some locations, where local defense groups have gained an advantage, such as in areas of Sagaing and Magway regions, ousted lawmakers and other activists have set up alternative governing systems (Myanmar Now, 12 November 2021). As well, many civil servants have continued the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM), refusing to work for the military junta and thus further denying the military the capacity to govern at the local level.

In an effort to further threaten civilians opposed to its rule, the military junta has supported the formation of local militias called Pyu Saw Htee (Frontier Myanmar, 14 June 2021). These militias have targeted civilians and have engaged in clashes with local defense forces. In 2021, ACLED records the most activity by Pyu Saw Htee groups in Sagaing region. Aside from the formation of military-backed militias, amid defections and a paucity of new recruits, the military has also ordered family members of soldiers to attend military training (Irrawaddy, 7 December 2021).

The response of ethnic armed groups to the military coup has been mixed. Notably, though, groups like the Kachin Independence Organization/Kachin Independence Army (KIO/KIA) and Karen National Union/Karen National Liberation Army (KNU/KNLA) have supported anti-coup activists who fled to their areas along the border. Battles in Kachin and Kayin states, which had been relatively limited in 2020, thus increased significantly in 2021. At times, troops from these groups have fought alongside local defense forces. For example, clashes between the military and the KIO/KIA have expanded into Sagaing region as the KIO/KIA has supported local defense groups. Sagaing region has been home to over one-fifth of all organized political violence recorded nationally since the coup.

What to watch for in 2022:

While the military staged its coup under the pretense of combating electoral fraud, and has since claimed it will hold new elections in 2023 (The Diplomat, 2 August 2021), it has subsequently set about systematically dismantling the NLD. NLD members have been detained on politically motivated charges. NLD offices have been destroyed, and members’ homes seized and sealed (Development Media Group, 2 December 2021). Further, the military and its militias have tortured and killed NLD members (BBC, 8 June 2021). The military looks poised to continue this campaign of violence against its main electoral opposition before holding any elections.

The military’s ongoing use of violence means that local defense forces are likely to continue to emerge in the coming year, while existing groups move towards forming alliances to strengthen their operating capacity. Alliances with ethnic armed groups are also likely to persist, despite the challenges of bringing such groups under the formal command of the NUG. The ability of local defense groups to gain and maintain control over territory – or at least prevent the military from being able to govern – will be critical to the success of the anti-coup movement. Coordination between armed and unarmed elements of the resistance movement will also be key in consolidating its gains (Myanmar Now, 21 January 2022). In 2022, resistance to the junta will continue, with the military unlikely to succeed in quelling a population so deeply opposed to its rule.

- Demonstrations: This term is used to refer collectively to all events coded with event type protests, as well as all events coded with sub-event type violent demonstration under the riots event type.

- Disorder: This term is used to refer collectively to both political violence and demonstrations.

- Event: The fundamental unit of observation in ACLED is the event. Events involve designated actors – e.g. a named rebel group, a militia or state forces. They occur at a specific named location (identified by name and geographic coordinates) and on a specific day. ACLED currently codes for six types of events and 25 types of sub-events, both violent and non-violent.

- Political violence: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s violence against civilians, battles, and explosions/remote violence event types, as well as the mob violence sub-event type of the riots event type. It excludes the protests event type. Political violence is defined as the use of force by a group with a political purpose or motivation.

- Organized political violence: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s violence against civilians, battles, and explosions/remote violence event types. It excludes the protests and riots event types. Political violence is defined as the use of force by a group with a political purpose or motivation. Mob violence is not included here as it is spontaneous (not organized) in nature.

- Violence targeting civilians: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s violence against civilians event type and the excessive force against protesters sub-event type of the protests event type, as well as specific explosions/remote violence events and riots events where civilians are directly targeted.

For more methodological information – including definitions for all event and sub-event types – please see the ACLED Codebook.