10 Conflicts to Worry About in 2022

The Sahel

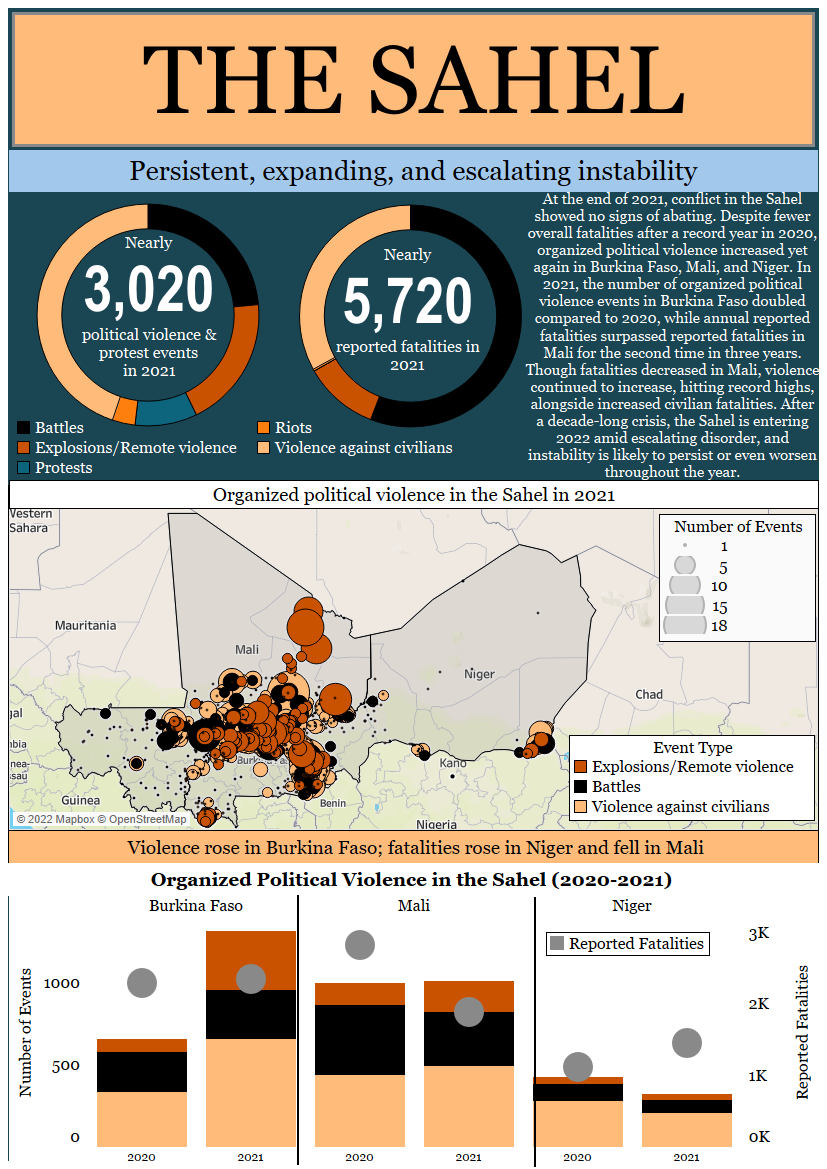

Persistent, expanding, and escalating instability

After a decade-long crisis, the Sahel entered 2022 amid escalating disorder, with levels of organized political violence increasing in 2021 compared to 2020. Conflict in the region has been largely driven by a jihadist insurgency centered in the states of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, which are most affected by the crisis. Each of these countries experienced significant instability in their own way in 2021. Spillover effects of the crisis on neighboring West African littoral states such as Ivory Coast and Benin also took on even greater proportions. Ongoing democratic backsliding and emerging competition among major powers have further complicated regional dynamics, although the overall impact remains to be seen.

Burkina Faso has replaced Mali as the epicenter of the regional conflict. In 2021, the number of organized political violence events in Burkina Faso doubled compared to 2020, while annual reported fatalities surpassed reported fatalities in Mali for the second time in three years.

The worsening violence in Burkina Faso has been largely driven by the Al Qaeda-affiliated Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), which increased activity across several regions in the country last year. The group’s engagement in political violence — including attacks on both civilians and state forces — increased over 200% in 2021 compared to 2020. JNIM-affiliated militants perpetrated multiple high-fatality attacks over the course of the year, including the deadliest attack on civilians ever recorded by ACLED in Burkina Faso. During that attack, JNIM-affiliated militants killed about 160 people in the town of Solhan, in Yagha province in June. High death tolls were also reported during militant attacks on state forces near Gorol Nyibi in Soum in August, and at the Inata gold mine in Soum in November.

Similarly, Niger experienced a record year of conflict, home to the highest number of civilian fatalities in the country since the beginning of ACLED coverage. The Greater Sahara faction of the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP-GS) was responsible for more than 560 reported civilian deaths, accounting for nearly 80% of all civilian fatalities in Niger in 2021. ISWAP-GS activity led to the formation of self-defense militias in many villages in the Tillaberi and Tahoua regions. In a June 2021 report, ACLED analysis indicated that mass atrocities and the arming of communities could escalate into a communal war. Since then, dozens of militants and militiamen have been killed in tit-for-tat attacks in the Tahoua region.

In the Torodi area of southwestern Tillaberi, JNIM continues to exert influence and is gradually advancing toward Niamey. This is evidenced by violent activity within 30 kilometers of the capital, including attacks on schools and government facilities as well as an attack on a joint force position. This progression comes despite successive large-scale operations — ‘Taanli’ and ‘Taanli 2’ — conducted by Nigerien and Burkinabe troops in June and between November and December 2021 (Le Faso, 27 June 2021; RTB, 9 December 2021).

Mali was the only country in the subregion that saw a decrease in conflict-related deaths last year. There are several developments and factors that, taken together, could explain this decline. Namely, civilian fatalities by Malian state forces decreased over 70% in 2021. The drop coincides with Malian forces reducing operations in 2021, having previously carried out significant attacks on civilians as part of counterinsurgency operations in 2020 (for more, see ACLED’s report: State Atrocities in the Sahel). This relative withdrawal occurred against the backdrop of military coups in August 2020 and May 2021. Instead of focusing on matters of security, the junta-led transitional government has largely focused on staying in power, prolonging the political transition, and delaying the holding of elections (AP, 7 June 2021; 2 January 2022). This has been evidenced by the limited engagement of Malian forces in joint operations alongside its neighbors.

Amid this military withdrawal, the Malian state and local defense militias have rapidly lost control of territory to JNIM and its affiliates. This is particularly pronounced in central Mali, where JNIM has waged relentless campaigns against Dan Na Ambassagou and Donso (or Dozo) militiamen. Bambara and Dogon farming communities associated with the Dan Na Ambassagou and Donso militias were targeted in three distinct areas, including Bandiagara and Djenné in the Mopti region, and Niono in the Segou region. Sustained pressure by JNIM has put the Dan Na Ambassagou and Donso militias on the defensive, with significant losses in October in Djenne and Niono, respectively. Not only were these the deadliest attacks on the Dan Na Ambassagou and Donso militiamen ever recorded by ACLED, they were also of strategic importance as JNIM forced the surrender of militiamen in both Djenne and Niono.

The worsening security situation across the Sahel has also amplified existing tensions over the ongoing presence of French forces in the region. Anti-French demonstrators in Niger and Burkina Faso have targeted French military convoys, prompting deadly interventions by French forces alongside local state forces. In Niger, French and Nigerien government forces opened fire on demonstrators when they attempted to vandalize a military convoy in Tera in November, killing three demonstrators and injuring 18. Meanwhile, coups in Mali and, more recently, Burkina Faso have further complicated French engagement in the region. The successive coups in Mali strained relations between Mali and France, and have created disharmony in the strategic military partnership (France 24, 3 June 2021). These relations have gradually deteriorated since France began reducing and reshaping its Barkhane mission, with a partial withdrawal from northern Mali (VOA, 30 September 2021). Since then, Mali has partnered with Russian military advisors or possibly the Russian private military company Wagner Group, who began accompanying Malian government forces during operations in central Mali in December 2021. The Russian deployment has stoked concerns among international actors engaged in Mali (ECFR, 2 December 2021). Diplomatic tensions have reached unprecedented levels, especially escalating after the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) imposed a new round of sanctions on Mali in January 2022 (Al Jazeera, 9 January 2022). In response, Mali denied international forces access to its airspace (DW, 20 January 2022), and expelled Danish troops deployed as part of the French-led European Task Force Takuba (Al Jazeera, 27 January 2022; Anadolu Agency, 21 January 2022). Mali also went so far as to expel the French ambassador to the country (Reuters, 31 January 2022).

The year 2021 was additionally marked by further geographic expansion of militant groups, including into West African littoral states. In mid-2020, JNIM began to establish a foothold in northern Ivory Coast (for more, see ACLED’s report: In Light of the Kafolo Attack), a presence that has evolved into a domestic problem beyond mere spillover during 2021 (ISS, 15 June 2021). Precursor activities observed in Benin also indicated a growing presence and the risk of spillover into the country (for more, see ACLED’s joint report with the Clingendael Institute: Laws of Attraction). This was confirmed by multiple armed clashes between Beninese forces and presumed militants in 2021, including militant attacks on Beninese military positions in Alibori and Atacora departments in late 2021, followed by the first two IED attacks recorded in Benin. In Togo, the first reported militant attack occurred in early November 2021, stemming from increased militant activity in Kompienga province in Burkina Faso. Similarly, the Koulpelogo and Boulgou provinces that border Ghana have experienced a sharp resurgence in militant activities following a more than two-year-long hiatus. The northernmost border areas of the littoral states host smuggling and trade routes that play an important role in the insurgent ecosystem (Clingendael, 22 December 2021). These routes ensure the logistical flow of JNIM and its affiliates, including fuel, supplies, motorcycles, gold, and ammunition. These illicit activities were reportedly disrupted prior to the recent attacks in Benin (Banouto, 1 December 2021), and may point to triggering mechanisms for this sudden shift in JNIM’s strategic calculus.

What to watch for in 2022:

The Sahel is undergoing a profound and unprecedented change at the military and political levels. The ongoing diplomatic imbroglio results from the compounding effects of successive coups d’état, the Malian junta’s collaboration with Russian forces, and the French transformation of Operation Barkhane. Combined, they have created significant fractures in the regional security project and called into question the Western-led military intervention. While Mali had largely withdrawn militarily from the fight against Islamist militant groups throughout the majority of 2021, it has again scaled up military operations since late 2021, in part alongside its new Russian partners. However, these operations have been accompanied by attacks on civilians in several regions, and there are signs that the downward trend for civilian fatalities in 2021 is now taking a turn for the worse.

France’s position is increasingly untenable in the face of growing anti-French sentiment, and France may look for more viable counterterrorism partners in Niger and Burkina Faso amid growing popular support for a French withdrawal from Mali. Meanwhile, Niger does not appear to want the French-led Takuba Task Force deployed on its soil (Le Figaro, 3 February 2022), and President Mohamed Bazoum may face internal pressure following the anti-France demonstrations that turned deadly near the town of Tera in November. In Burkina Faso, a military coup occurred in January 2022 amid a joint Burkinabe and French operation called ‘Laabingol.’ That a military junta now rules the country makes it morally questionable whether France should seek a stronger military presence there and if it would be accepted by the Burkinabes.

Despite gains in 2021, the insurgency is currently experiencing a downturn at the military level due to accumulating militant casualties in the face of ongoing campaigns by state forces. Against this military pressure, JNIM in particular has stepped up efforts to target schools and telecommunications infrastructure, with such activity increasing in November 2021 and January 2022, respectively. JNIM has also sought to expand its operations in several regions of Burkina Faso, where border areas with neighboring countries are turning into a major battleground. The recent spillover into Benin and Togo has the potential to follow a similar evolution as that which developed in northern Ivory Coast. The risk of spread and escalation could be even higher, considering the greater presence of militants in Kompienga.

If the spillover into the littoral states is indicative of a spread of militancy, it is also evident in countries primarily affected by the Sahel crisis. The need for joint military operations between the affected countries is becoming more frequent. These regular joint operations highlight the steadily deteriorating security situation, albeit in a more favorable light, and underscore that coordination and cooperation between countries in the region are improving to counter the common threat. While Burkina Faso, by necessity, maintained the highest operational tempo in the region at the military level and played a central role in joint military operations during 2021, it also struggled to contain the violence. In 2022, these efforts may eventually be overwhelmed, unless countries in the region continue to join forces and pool their resources to address the common threat or find alternative ways to contain the violence.

- Demonstrations: This term is used to refer collectively to all events coded with event type protests, as well as all events coded with sub-event type violent demonstration under the riots event type.

- Disorder: This term is used to refer collectively to both political violence and demonstrations.

- Event: The fundamental unit of observation in ACLED is the event. Events involve designated actors – e.g. a named rebel group, a militia or state forces. They occur at a specific named location (identified by name and geographic coordinates) and on a specific day. ACLED currently codes for six types of events and 25 types of sub-events, both violent and non-violent.

- Political violence: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s violence against civilians, battles, and explosions/remote violence event types, as well as the mob violence sub-event type of the riots event type. It excludes the protests event type. Political violence is defined as the use of force by a group with a political purpose or motivation.

- Organized political violence: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s violence against civilians, battles, and explosions/remote violence event types. It excludes the protests and riots event types. Political violence is defined as the use of force by a group with a political purpose or motivation. Mob violence is not included here as it is spontaneous (not organized) in nature.

- Violence targeting civilians: This term is used to refer collectively to ACLED’s violence against civilians event type and the excessive force against protesters sub-event type of the protests event type, as well as specific explosions/remote violence events and riots events where civilians are directly targeted.

For more methodological information – including definitions for all event and sub-event types – please see the ACLED Codebook.