The decision by Burundian president Pierre Nkurunziza to push for a third term in government has pulled the country into its most intractable political crisis since the end of the 2005 civil war. Protests started in late April and quickly escalated to include riots, grenade attacks and the targeted lynching of those suspected of being part of the feared Imbonerakure, the youth wing of the ruling National Council for the Defense of Democracy – Forces for the Defense of Democracy (CNDD-FDD).

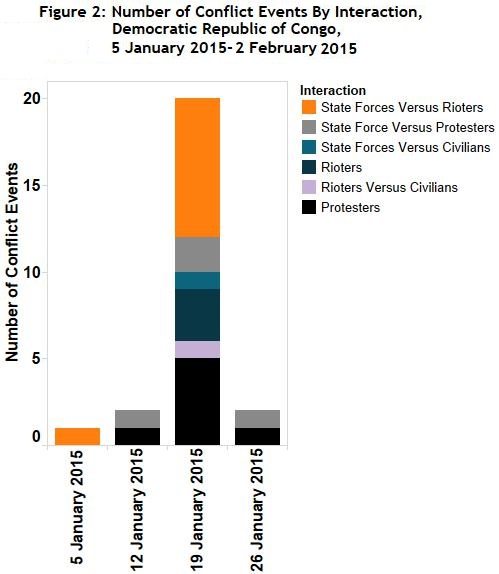

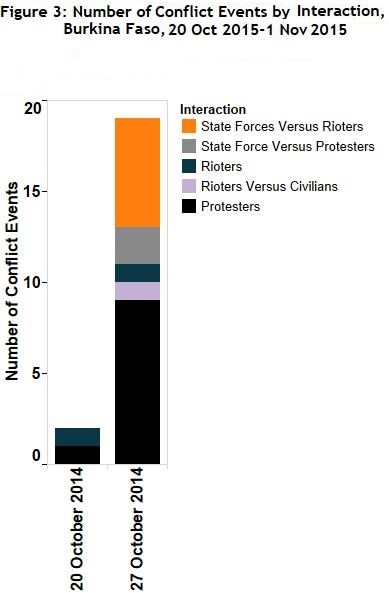

Nkurunziza’s bid to extend his tenure as ruler comes on the back of two unsuccessful attempts by African leaders to alter legislation aimed at limiting their terms. Long-standing president of Burkina Faso, Blaise Compaoré, was ousted by popular protest after attempting to change the constitutional limit to run for a third term. In DR Congo, Joseph Kabila faced his first two major defeats in the legislature after attempting to hold onto power by first altering the constitution and then by pushing for elections to be postponed until after a lengthy census (Africa Confidential, 9 January 2015; Africa Confidential, 6 February 2015). Popular demonstrations against Kabila, and the resultant crackdown from the security forces, resulted in the loss of approximately 40 lives (ibid).

While the political crises in the DR Congo and Burkina Faso were resolved by the incumbent acquiescing, to some degree, to the protesters demands, no significant compromises or agreements have been reached in Burundi in the two months since the crisis started. The opposition has suspended its involvement in the United-Nations brokered negotiations in the aftermath of the assassination of opposition politician Zedi Feruzi while Nkurunziza, perhaps emboldened by his successful defeat of an attempted coup by sections of the military, has started purging those opposed to his third term from the CNDD-FDD (Africa Confidential, 29 May 2015).

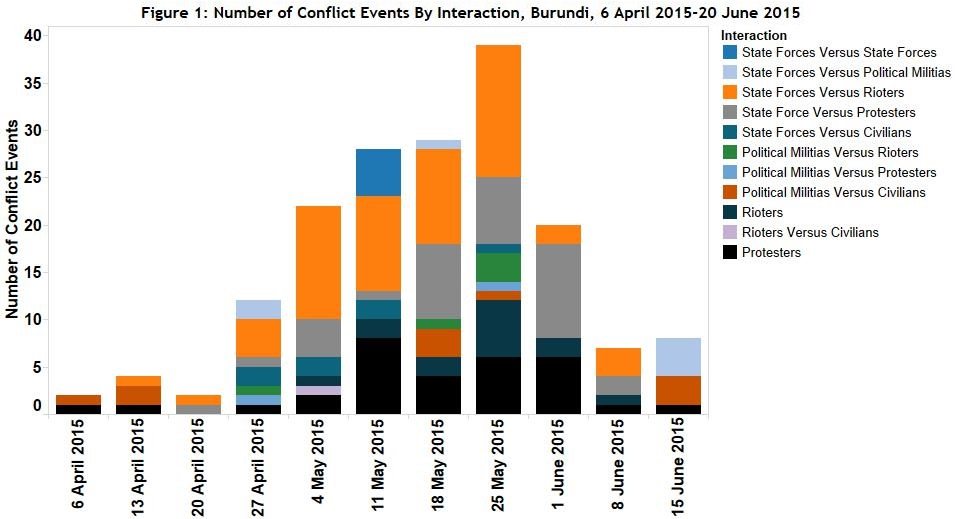

Figure 1 shows that while overall events have decreased markedly in the past few weeks, the composition of the political violence has shifted from clashes between rioters and state forces to battles between state forces and political militias and the targeted assassinations of civilians by unidentified groups. Recently, dissent and opposition to the ruling regime has taken on a more insurgent character with CNDD-FDD politicians and security forces being targeted by grenade attacks (Africa Times News, 22 June 2015).

This increase in political militia marks a contrast to the cases of DR Congo and Burkina Faso in which riots and protests remained the main methods of dissent (See figures 2 and 3). This shift in tactics may be due to the duration of the Burundian crisis. While the political crisis in DR Congo was resolved within four weeks and the Burkinabe uprising was finished within a fortnight, the political impasse in Burundi has dragged on for over ten weeks with no end in sight. Given the inability of protest to drive reform opposition activists may be starting to resort to more deadly and direct tactics.

AfricaAnalysisCivilians At RiskEthnic MilitiasFocus On MilitiasGovernment RepressionLocal-Level ViolencePolitical StabilityRioting And ProtestsViolence Against Civilians