2015 has so far been the most active year for South Africa in the ACLED dataset, with over 1,400 individual political violence and protest events taking place since the beginning of January. This represents a 33% increase over 2014. In spite of this change in aggregate events, the instability profile for South Africa remained similar to that of previous years. Riots and protests remained the most common form of reported political disturbance event, accounting for 84.5% of all events in 2015.

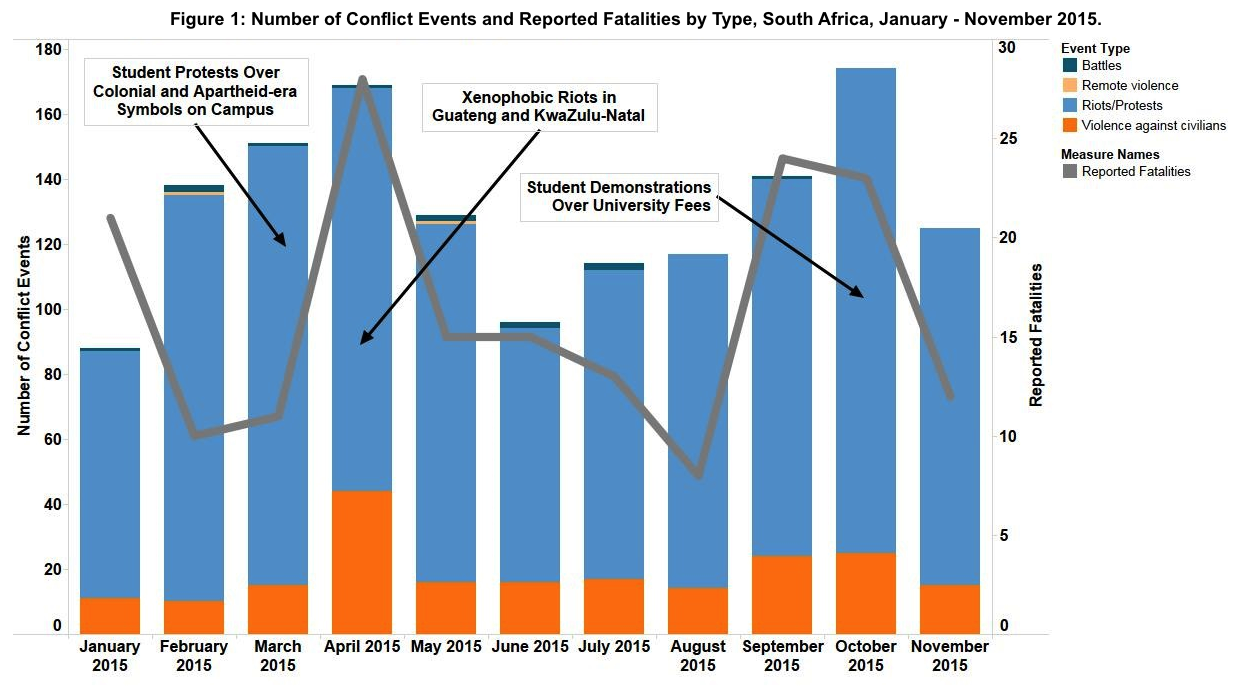

Three major events in South Africa are responsible for the increase in political instability: the protests over social transformation at multiple universities in South Africa in March, the xenophobic riots in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng in April, and the recent demonstrations over university fees.

Protests over ‘transformation’ laid bare the culturally based frustrations of the so-called ‘Born Free’ generation. In March, students began to demonstrate against the enduring presence of colonial and Apartheid-era cultural relics on university campuses. The most famous of these demonstrations was at the University of Cape Town where students demanded that the statue of Cecil Rhodes, the British Imperialist who donated land to the university, be removed from campus (Rhodes Must Fall, 2015). Similar demonstrations took place in Stellenbosch University where students demanded that English replace Afrikaans as the language of instruction (Shabangu, 28 August 2015).

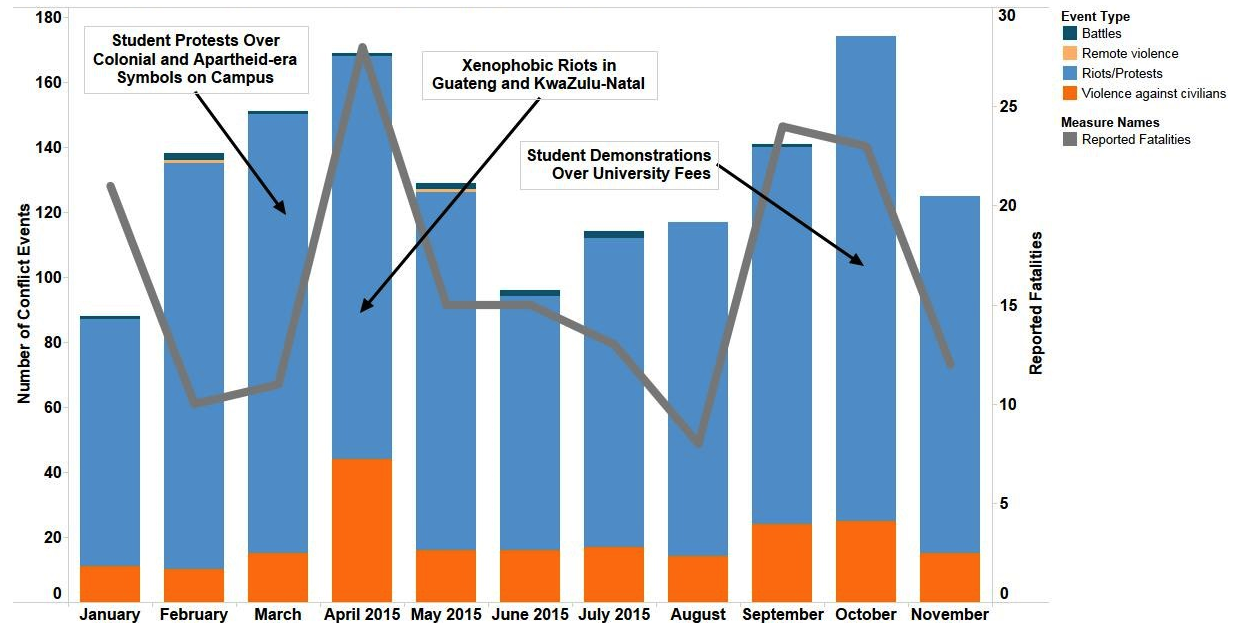

There were two major outbursts of xenophobic violence in South Africa in 2015. The first took place in Soweto in January after a Somali shopkeeper shot a South African teenager allegedly attempting to steal from his shop. The second larger outbreak took place in April after the Zulu monarch, King Goodwill Zwelithini, made a speech demanding that migrants and foreigners leave South Africa (Times Live, 16 April 2015). Within a matter of days the violence spread to Gauteng with Johannesburg being particularly hard hit. The lethality of this second outbreak meant that April had the highest number of instability related deaths and the highest level of violence against civilians in 2015 (see Figure 1).

Xenophobic attitudes are prevalent in parts of South Africa. A survey of over 27,000 individuals in Gauteng, the epicentre of anti-foreigner violence during 2015 and 2008, finding that 35% of respondents believed that all foreigners should be sent home (SAPA, 14 August 2015). However, during the 2008 violence local community leaders allegedly capitalised on anti-foreigner sentiment to shore up local support and enhance their chances of being elected to lucrative local government positions (Landau and Misago, 2009).

In the aftermath of the violence, the government launched Operation Feila. Nominally an operation to fight crime, it has resulted in the repatriation of over 15,000 undocumented migrants leading to accusations of state-sponsored xenophobia (Maromo, 7 September 2015). However, South Africa only suffered from minor outbreaks of xenophobic violence after April. It is unclear whether this is due to Operation Feila or due to other factors such as an exodus of foreign-nationals from violence hotspots.

October was the most active unstable month of 2015. This is due to nation-wide demonstrations by students over increasing tuition fees. The recent demonstrations were sparked after some universities announced that they were increasing their fees by 10%, double the rate of inflation. The issue was compounded by the fact that the National Student Financial Aid Scheme announced that it lacked the funds to provide assistance to all qualifying students (Hall, 29 October 2015).

Of the main upheavals in South Africa, the nationwide demonstrations over university funding garnered the most conciliatory reaction from the government. The ruling ANC vocally condemned the violence of the xenophobic riots and later clashed with the Rhodes Must Fall movement (Bernardo, 31 August 2015; Agence France Presse, 15 April 2015). However, the government attempted to negotiate with the fee demonstrators. Higher Education Minister Blade Nzimande initially offered a 6% cap of fee increases and President Zuma eventually capitulated to the student’s demands and announced that there would be no fee increases for the next year (BBC News, 23 October 2015).

The government’s willingness to negotiate with students over fees may be due to how widespread the demonstrations were compared to the comparatively contained protests over transformation at the universities.

All three of these issues are likely to resurface during next year’s municipal elections. The role local community leaders have played in facilitating xenophobic violence in the past raises the possibility that local party representatives may again encourage anti-foreigner violence to shore up support. Similarly, the economic and cultural issues faced by South African students are again likely to be key issues. The two major opposition parties, the Democratic Alliance and the Economic Freedom Fighters, both claimed to support the anti-fee demonstrations. It may be the case that students again use riots or protests to remind the ANC of their numerical strength and their vital importance as a constituency in the forthcoming elections.

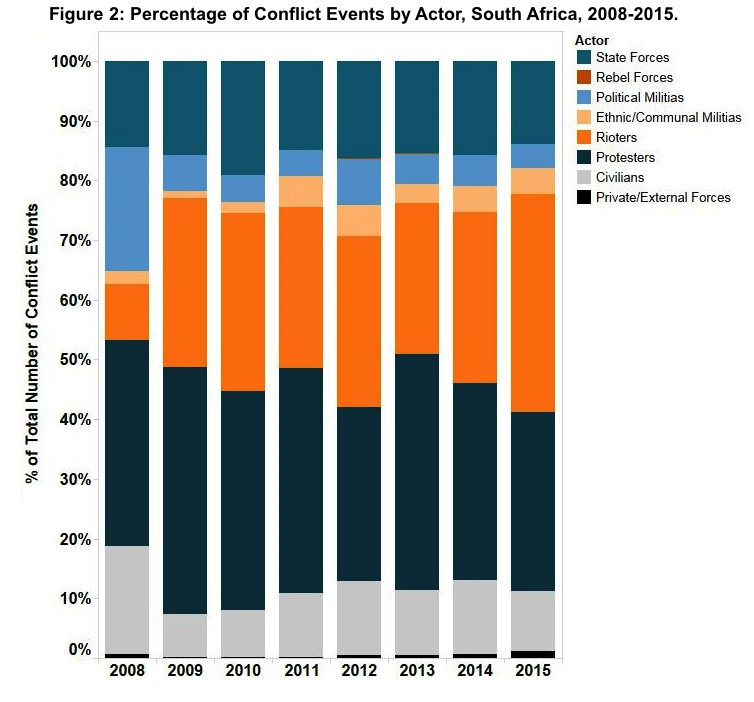

Over the past few years, there has been a relative decrease in peaceful protests in South Africa. Events involving peaceful protesters accounted for 40% of events in 2013, 32.9% of events in 2014 and 30% of events in 2015. This has been matched by a relative increase in events involving violent rioters, which have accounted for 25.3%, 28.7% and 36.4% of events in 2013, 2014 and 2015 respectively (see Figure 2). This shows that violent demonstration is becoming a more acceptable means to vocalise political discontent. Given the importance of the municipal elections and the virulence of the main political events in 2015, violent demonstration may become even more prevalent and widespread next year.

This report was originally featured in the December ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.