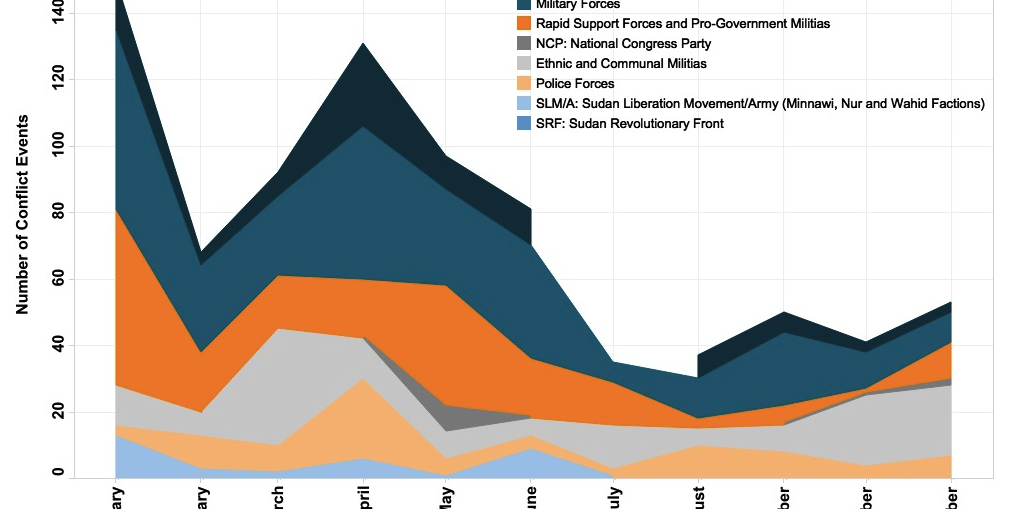

In 2015, both Sudan and South Sudan experimented with peace talks and peace agreements with their respective opposition groups, with varying effects on conflict events in each country. Despite stalled talks and ceasefires in Sudan, the number of conflict events in the country decreased in the second half of 2015 (see Figure 1). In late November, an African Union mediation team announced the suspension of a tenth round of peace talks between the Government of Sudan and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N). Talks also stalled between the government, the Justice and Equality Movement, and the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army-Minnawi Faction. Regardless, a drop in military and pro-government militia activity is responsible for the overall decrease in conflict events. Such actors were 83 percent less active in November compared to January (see Figure 1). Government militia activity peaked in January, as Rapid Support Forces (RSF) ‘cleansed’ villages and water resources throughout North Darfur. Military activity was also prevalent at the start of the year, as the Sudanese Air Force carried out bombing raids in villages in South Darfur and South Kordofan. Military, RSF and pro-government militias continued to be the most dominant actors in Sudan until mid-2015 (see Figure 1).

In April, the International Crisis Group predicted that the military’s continued reliance on militias would lead to increased communal violence, particularly in Darfur (International Crisis Group, 22 April 2015). Since July, ethnic and communal violence has indeed increased with 39 conflict events in October and November (see Figure 1). This represents a delayed effect of RSF attacks on civilians throughout 2014 and 2015, which forced Darfuri farmers to flee to El Salam camp. The South Darfur authorities then distributed farmlands from the Rizaygat tribe to Abala camel herders (Radio Dabanga, 1 December 2015). Over the past two months, Abala tribesmen have whipped farmers and torched homes in numerous villages in North Darfur to prevent displaced farmers from reclaiming their lands. Ethnic violence has also occurred between Salamat and Misseriya militias in Central Darfur, resulting in seven fatalities in October.

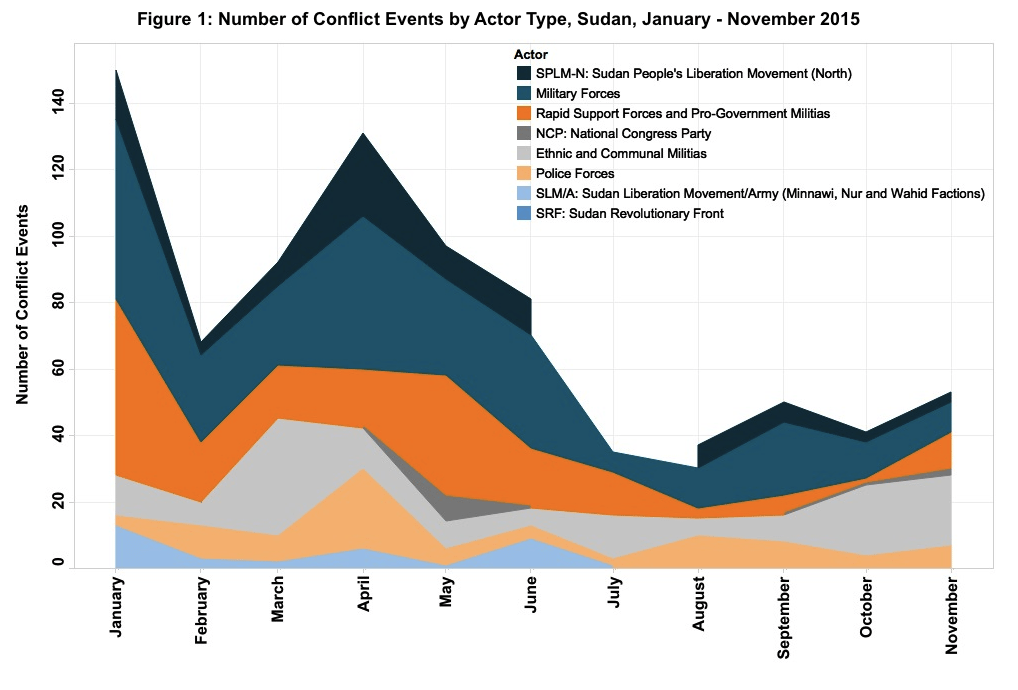

Despite an increase in ethnic and communal violence, Sudan has experienced a decrease in rebel fighting as the year draws to a close. This is partly due to a decline in conflict events involving SPLM-N, active predominantly in the southern states of Kordofan and Blue Nile. SPLM-N was involved in only two battles in November compared to ten in June (see Figure 2). However, early December brought reports of troop movement and a replenishment of vehicles and ammunition to military bases in Kurmuk in Blue Nile (Radio Dabanga, 1 December 2015). SPLM-N forces are also likely taking advantage of the lull in fighting to rearm and replenish food supplies. SPLM-N activity peaked in April during presidential elections that saw Omar al-Bashir reelected with less than half of registered voters going to the polls (see Figure 1). The opposition group shelled villages, polling stations and military bases in South Kordofan during the elections, killing 80 people.

A complete cessation of hostilities between the military and all rebel groups seems far off, as multiple parties feel excluded from the negotiating process. Three rebel groups in Darfur recently demanded to join peace talks in Addis Ababa: Sudan Liberation Movement/Army-Second Revolution, New Sudanese Justice and Equality Movement, and Sudan Liberation Movement for Justice (Sudan Tribune, 1 December 2015). All three groups want a distinct peace process to negotiate the Darfur conflict separately from other national issues. Adding to tensions between pro-government groups and Darfuri groups is October’s small but troublesome reemergence of violence against Darfuri university students. On 13 October, students of the ruling National Congress Party (NCP), backed by National Intelligence and Security Services (NISS), attacked Darfuri students with machetes and guns during a protest at Holy Koran University in Omdurman. Similar violence erupted in late April, when 150 NCP students attacked a Darfur Students’ Association meeting at Sharg el Nil University in Khartoum. At the height of such violence in May, NCP and NISS injured or detained at least 70 people on various campuses and abducted eight students from the University of Dongola (Radio Dabanga, 19 May 2015). Such violence brings fears of a new forum for ethnic cleansing where members of Darfuri tribes not only face threats and acts of violence at home, but also in urban cities throughout the country.

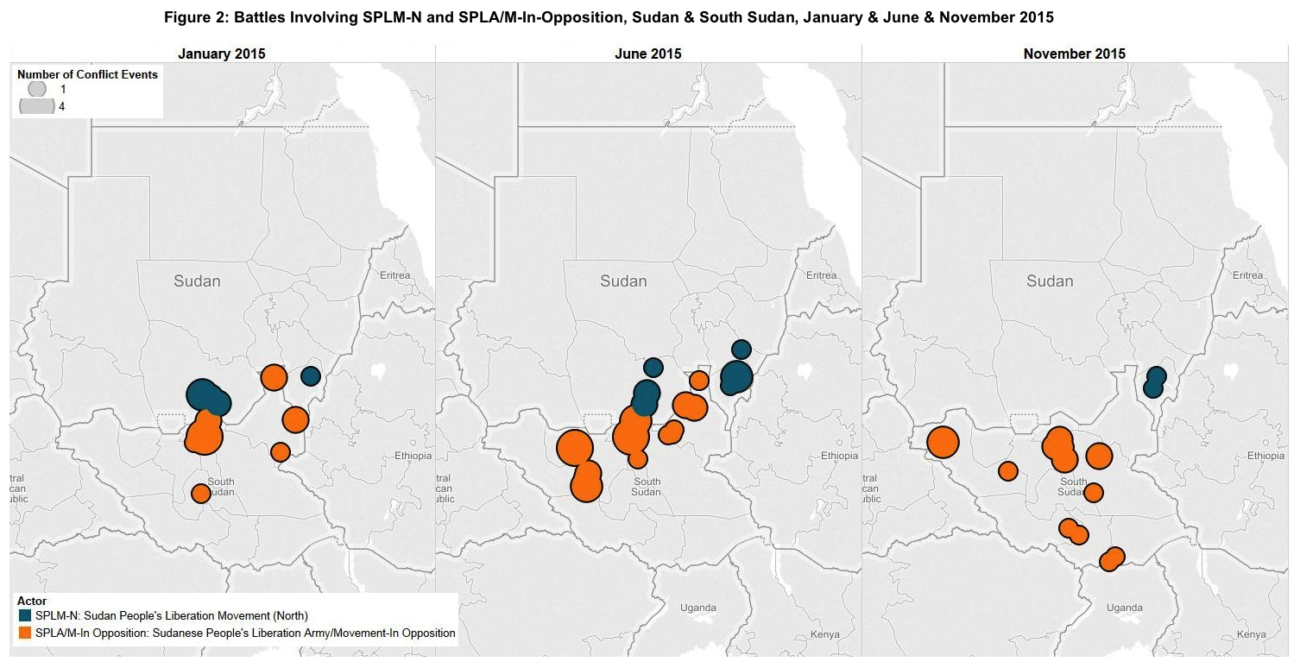

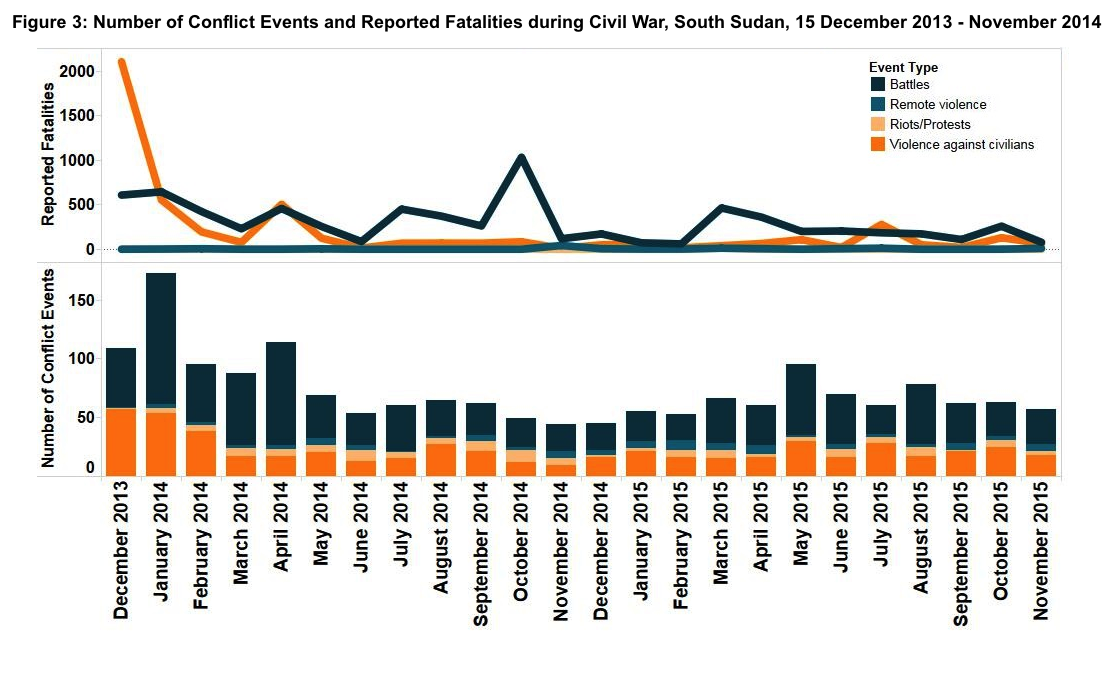

On 15 December 2015, South Sudan will enter its third year of civil war. Despite the longevity of the conflict, November 2015 saw the lowest number of conflict events (57) since February 2015 (see Figure 3). This decrease may be a product of the government’s decision earlier in the year to postpone June’s scheduled elections in the interest of ongoing peace negotiations; parliament since extended President Salva Kiir’s term until 2017 (Reuters, 14 February 2015). On 26 August, the government and former Vice President Riek Machar’s Sudanese People’s Liberation Army/Movement-In Opposition (SPLA/M-IO) signed a peace agreement (Al Jazeera, 27 August 2015). In the days between the signing and the implementation of a ceasefire, clashes briefly escalated between SPLA/M-IO and military forces in the oil-rich states of Unity and Upper Nile bordering Sudan. Throughout the year, as control over northeastern cities of Malakal and Nyal changed hands multiple times, SPLA/M-IO activity also stretched into western and southern areas of the country (see Figure 2). In November, SPLA/M-IO battles occurred throughout Western Bahr el Ghazal, Western Equatoria and Eastern Equatoria, as the military attacked rebel camps in Magwi and Opari.

The first month of the conflict is one of only three months (see April 2014 and July 2015) in which incidences of violence against civilians caused more fatalities than did battles (December 2013 reported 2,108 fatalities from violence against civilians) (see Figure 3). However, civilian casualties still occur on battlegrounds in South Sudan. Clashes in Adok and Thonyor villages on 29 August resulted in the deaths of 56 civilians from the Nuer ethnic group. Rebels claim that soldiers raped women in Mayendit, Koch and Leer. Tensions between soldiers and local citizens also escalated earlier in the year in Mundri, when heavily armed Dinka herders moved their cattle onto Western Equatoria farmland (Al Jazeera, 21 November 2015). The move sparked back-and-forth revenge clashes between soldiers siding with the Dinka herders and local groups protecting their lands. Continuing tensions in the area could inhibit the implementation of a peace agreement, as many armed youths do not want to disarm and receive amnesty promised by the government: “Many refuse to [disarm], demanding that Dinka elements of the army they hold responsible for killing civilians be replaced by local forces” (Al Jazeera, 21 November 2015).

Another hurdle to implementing the recently signed peace deal will be the outcome of a unilateral presidential order – approved by parliament – to divide South Sudan’s ten existing states into 28 states. The proposed divisions are largely ethnic-based, for instance, separating Dinka and Nuer tribes in Upper Nile State. SPLA/M-IO has called on international organisations, such as the United Nations, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development and Troika, to reverse the decree. Machar’s spokesperson James Gatdet Dak contends that a transitional government must address the designation of new states through the creation of a new constitution (Sudan Tribune, 26 November 2015). The controversial order has already led to the formation of new rebel groups. In protest of the 28-states plan, military defectors of the Shilluk ethnic group formed the Tiger Faction New Forces (TFNF). In Eastern Equatoria, the South Sudan Armed Forces (SSAF), led by Anthony Ongwaja and consisting predominantly of Latuka ethnic group members, say that the government “has lost [its] historical vision for the people” (Sudan Tribune, 5 December 2015). The rapid formation of new and splintered groups adds to the already complex array of rebel factions, defections and mergers that are sure to complicate the implementation of South Sudan’s existing peace agreement.

This report was originally featured in the December ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.