Throughout 2015, multiple theatres of violence played out over the Libyan territory. Two prominent dynamics shaped the trajectories of violence in 2015, providing the foundation for the conflict patterns present in early 2016. The first was the continuation of violence between Operation Dignity and Operation Libya Dawn forces that led to the erosion of political salience held by brigades from Misrata. The second and perhaps most evident trend in 2015 was the rise in prominence of Islamic State (IS) affiliate groups in the midst of the civil conflict.

Misratan Brigades initially engaged with the Libya National Army (LNA) and pro-government militias from Zintan from January – March for control over the eastern oil ports of Al-Sidra and Ben Jawad. In March, this contest de-escalated as Misratan forces pulled out to concentrate their firepower on Sirte where IS forces began consolidating their position.

This period represents a turning point in the 2015 violence, punctuated by the 166 Brigade’s withdrawal from Sirte in late May. The withdrawal signified mounting friction between the General National Congress (GNC) and, at the time, its de facto fighting force from Misrata. Misratan forces withdrew owing to a lack of resources, as combatants overextended their military capacity and as the GNC withheld reinforcements and military hardware (Middle East Eye, 30 May 2015). From May onwards, Misrata’s role in the conflict declined as splintering alliances resulted in a number of communal brigades — once allied to Misrata and Operation Libya Dawn — acting autonomously and vying for political inclusion.

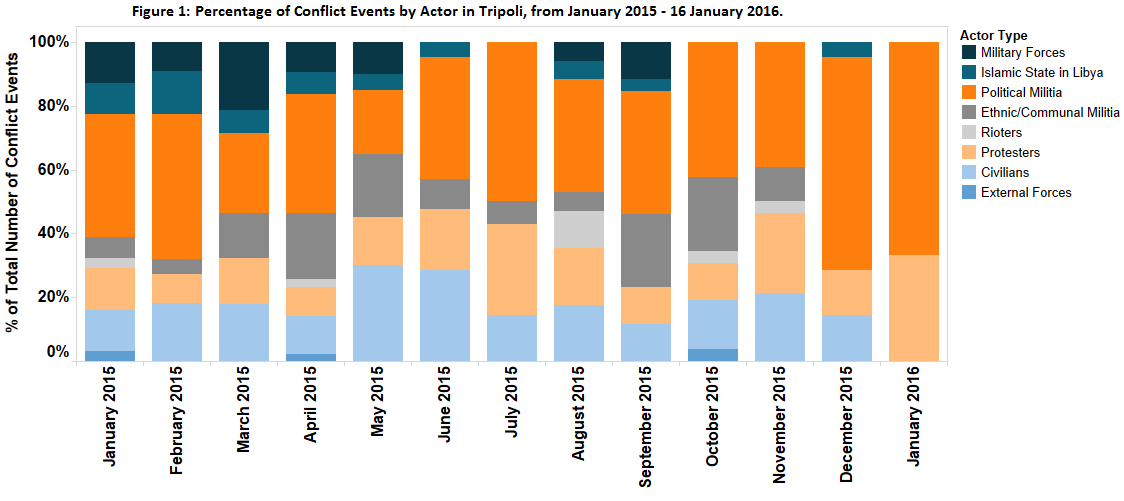

As Misrata tightened its grip on administering and securing Tripoli, a number of Tripoli brigades responded by intensifying communal clashes towards the end of 2015 and January 2016 (see Figure 1). Although the Special Deterrence Force (Rada) acts under the remit of the Ministry of Interior to prevent crime and police Tripoli, the Tripoli Revolutionaries Brigade/1st Company controlled by Haitem Tajuri, and the Abu Saleem Brigade militia leader Abdul Ghani Al-Kikli (“Ghneiwa”) scaled their attempts to assert dominance for local power and control of the capital in the final quarter of 2015. Constituting two-thirds of all conflict in Tripoli in December 2015 and January 2016 (see Figure 1), the brigades of these powerful figures turned their attention away from Misratan brigades onto each other.

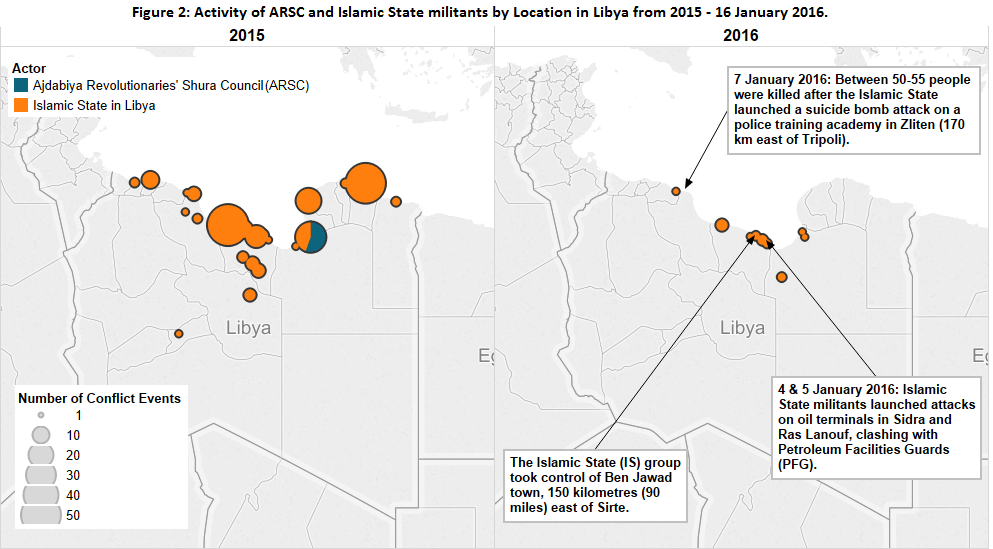

The first week of 2016 witnessed a massive escalation of violence conducted by IS militants. A series of suicide attacks targeted security forces around the country, threatening Eastern and Western Libya (see Figure 2). These attacks come after growing activity in Ajdabiya, where daily assassinations and remote violence attacks against Salafi groups and security forces were widespread. A group of fighters from the Ajdabiya Revolutionaries Shura Council (ARSC) pledged allegiance to the IS on 31 December. Similar to pledges by other Islamist groups across North Africa, the council’s central leadership denied the pledge was representative of the group as a whole, blaming individuals (SITE Intel Group, 5 January 2016; BBC News, 11 January 2016), though it does emphasise continued expansion from small cells to a more coordinated entity.

In the days that followed, a massive car bomb attack struck a police training academy in Zliten, killing between 50 and 60 people (see Figure 2). The attack was similar in scale to the one launched in Al Qubbah in February 2015, also claimed by IS. The group also successfully took full control of Ben Jawad, previously used by Libya Dawn militias. From here, the group conducted a series of attacks on oil terminals at Sidra and Ras Lanuf, clashing with the Petroleum Facilities Guards (PFG) that had nominally supported the internationally-recognised government until its leader Ibrahim Jathran fell out of favour with General Khalifa Haftar, accusing him of attempting to kill him in an LNA airstrike (Libya Observer, 10 September 2015).

It is unclear whether IS intended to seize control of the terminals in the Oil Crescent, but these attacks demonstrate the capabilities of the IS in Libya group to exploit the coastal road for rapid offensives that have so far spread from Zliten to Derna — a distance over 1,100km [see Libya Security Monitor, 5 January 2016 for Map of IS Control and Attack Zones in Libya].

Targeting oil institutions suggests an intent to control the production and export of oil to finance their activity. However, although overall IS operations rose throughout 2015, the share of fatalities from violence against civilians decreased from 28.4% in 2013, to 8.7% in 2015 and their activity appears characterised by diffusion rather than growing strength (ACLED, September 2015). These latest attacks could well be an attempt to reassert their presence within their Libyan enclave, at a time when the rival parliaments were making steps towards a unity government, and as reports suggest the group has lost 30% of its territory in Iraq and Syria (International Business Times, 6 January 2016).

Although a unity government formed of a 32-member cabinet was finally announced on 19 January, questions hang over its ability to govern. The capricious behaviour of stakeholders in the peace accord and unresolved disputes appear ever present, as angry protests sprung up in reaction to the visit of Prime Minister of UN-imposed government Fayaz Sirraj in Western Libya including Zliten, Misrata and Tripoli on 8 January. Whilst new armed group coalitions are forming to tackle IS — such as the Petroleum Facilities Guards (PFG) and Ajdabiya Border Division (LANA, 12 January 2016) — they seem more likely to widen political antagonisms and erode the ability of a cohesive military force rather than unify them under a central command. The coming weeks are set to see a mélange of local brigades, militias and quasi-military groups intensify their organisational efforts to combat IS in rebel-held areas such as Sirte.

This report was originally featured in the January ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.