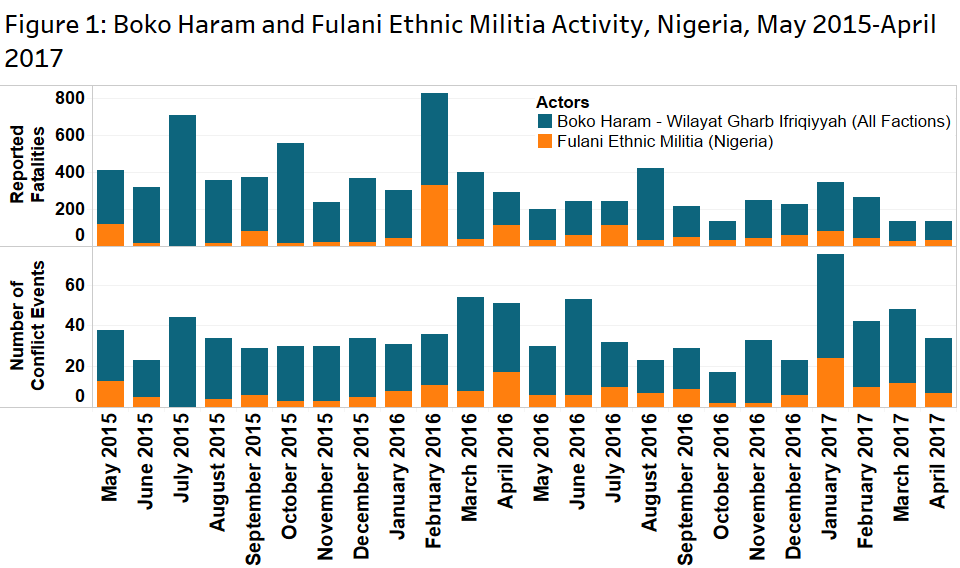

Levels of political conflict have continued to decrease in Nigeria throughout 2017. The drop in political violence seems to stem from the reduced activity of two of Nigeria’s most active and lethal conflict actors, the Fulani and Boko Haram (see Figure 1).

Boko Haram’s capacity to fight against the state or to inflict violence against civilians remains severely diminished with most activity relegated to small raids on army posts and suicide bombings (Anyadike, 4 May 2017). These bombings typically rely on delivering young women to crowded urban areas to detonate suicide vest. However, these attacks are decreasing in lethality and are increasingly concentrated in the group’s Borno base. In 2015, the average fatality count for Boko Haram suicide attacks was 15, in 2016 it was 9 and so far in 2017, an average of 3.4 people have died in each suicide attack by the group. While in 2015, 35.7% of the group’s suicide attacks took place outside of Borno state, in 2017 the figure is only 7.1%. This indicates that the Nigerian security services are becoming more adept at countering Boko Haram’s main tactic of destabilisation.

The diminished activity may also be fed by the ‘Safe Corridor’ initiative, launched a year ago, which enables Boko Haram foot soldiers to surrender and be reintegrated back into their respective communities (Anyadike, 4 May 2017). Similar projects are being quietly piloted in Niger as well (Rackely, 20 April 2017). Both projects appear successful in draining Boko Haram’s manpower.

Activity by Fulani militias has also decreased in lethality compared to previous years. Conflict tends to spike during the dry season (September-May) as herdsman move their cattle southwards for available pastures and water (Roseline and Amusain, 2017). Violent conflict events involving Fulani has followed this pattern with activity rising from October 2016 and reaching an apex this January. But in spite of a large number of conflict events, fatalities remain comparatively low compared to last year. In 2016, the average number of fatalities for an event involving Fulani militias was 10, in 2017, it is 3.5. Another major trend is that incidences of political involving Fulani militias are increasingly witnessed in the far southern states of Delta, Abia and Ogun. The reaction of southern states to these incursions has not been conciliatory, with Bayelsa state rejecting a federal bill to establish grazing reserves across the country and Abia and Ekiti state passing anti-grazing laws to prosecute those who destroy farm crops (Vanguard, 16 November 2016; Vanguard, 22 October 2016). These activities may further stoke tensions between indigenes and the migrating pastoralists, but the wariness of the southern states to the Fulani may also lead to increased deployment of security personnel and limit the violence.