Of the fourteen United Nations (UN) peacekeeping missions currently active around the world, half are based on the African continent. Of these, five—those in Somalia[1], Mali, the Central African Republic, South Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of Congo– have ongoing or recently renewed mandates, and a force of over 10,000 personnel, including soldiers and police.

The objectives, activity, and consequences of these UN peacekeeping missions vary widely, but can be broadly categorized in three ways, each of which determines how the peacekeeping mission will manifest on the ground:

- UN peacekeeping missions with a mandate addressing a specific, named threat. These missions will often require active engagement in violent conflict against a particular conflict actor.

- UN peacekeeping missions with a mandate concerning broad threats to peace and stability, which may change over time. These missions will often engage in different ways with different conflict actors, and these engagements vary over time.

- UN peacekeeping missions with a mandate intending to address the host state itself. These missions will engage directly with the host nation or its proxy forces, sometimes violently.

While peacekeeping missions can be categorized in this way, they are nevertheless as varied as the countries in which they operate. The table below offers descriptives around these missions, noting the differences in their size, budget, duration, and losses.

Peacekeeping Missions in Africa with Ongoing/Recently Renewed Mandates and 10,000+ Personnel

| Country | Size of Mission | Mission Budget | Years Mission Has Been Active | UN Mission Total Fatalities | Number of Total Violent Events in Country (2017) |

| Mali[2] | 15,156 Total Personnel (as of March 2018) | $1,048,000,000 (for 07/2017– 06/2018) | 5 years (since 25 April 2013) | 166 | 864 |

| Somalia[3] | 22,126 Total Personnel | ~$900,000,000 in 2016 | 11 years (since 19 January 2007) | ~500 lowest estimate (as of 2015) | 5434 |

| Central African Republic (CAR)[4] | 14,094 Total Personnel (as of March 2018) | $ 882,800,000 (for 07/2017– 06/2018) | 4 years (since 10 April 2014) | 60 | 716 |

| South Sudan[5] | 17,965 Total Personnel (as of March 2018) | $1,071,000,000 (for 07/2017– 06/2018) | 7 years (since 08 July 2011) | 55 | 2112 |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)[6] | 20,654 Total Personnel (as of March 2018) | $1,141,848,100 (for 07/2017– 06/2018) | 8 years (since 01 July 2010) | 145 | 1775 |

UN peacekeeping missions are intended to provide capacity-building and logistical support to war-torn countries transitioning from conflict to peace, but the scope of each mission’s work is more diverse than this mission statement might suggest. Peacekeeping missions undertake a wide variety of tasks to these ends, including protecting civilians, helping maintain security, supporting elections and other political processes, and promoting human rights. UN peacekeeping operations follow three guidelines in carrying out their operations: (1) maintain the consent of the main parties to the conflict, (2) keep an impartial focus on objective peacekeeping, and (3) restrict force except in self-defense and in defense of the mandate. These principles are universal; nevertheless, the degree to which they hold true depends on the nature of a specific mission’s goals, and the context in which it operates. Indeed, some UN missions seek to keep the peace through the targeted breaking of these ground rules.

- UN Peacekeepers as Active Combatants

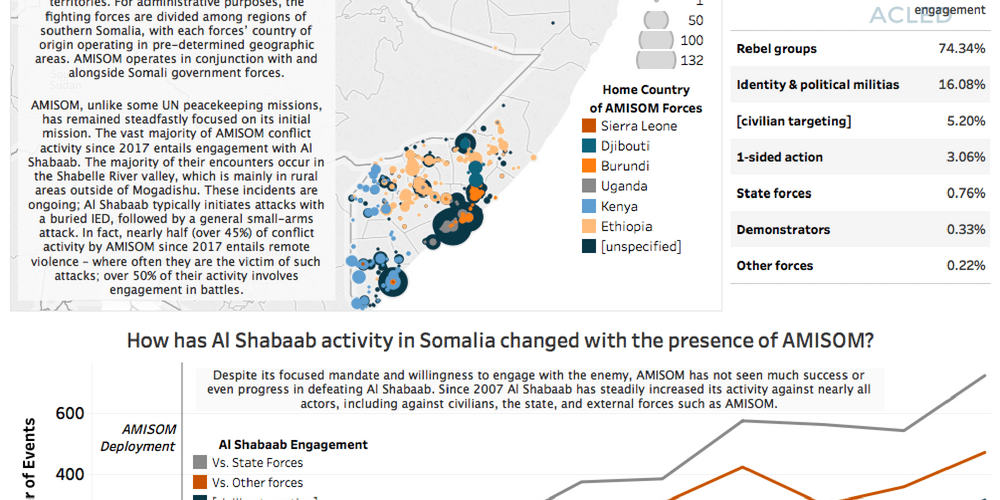

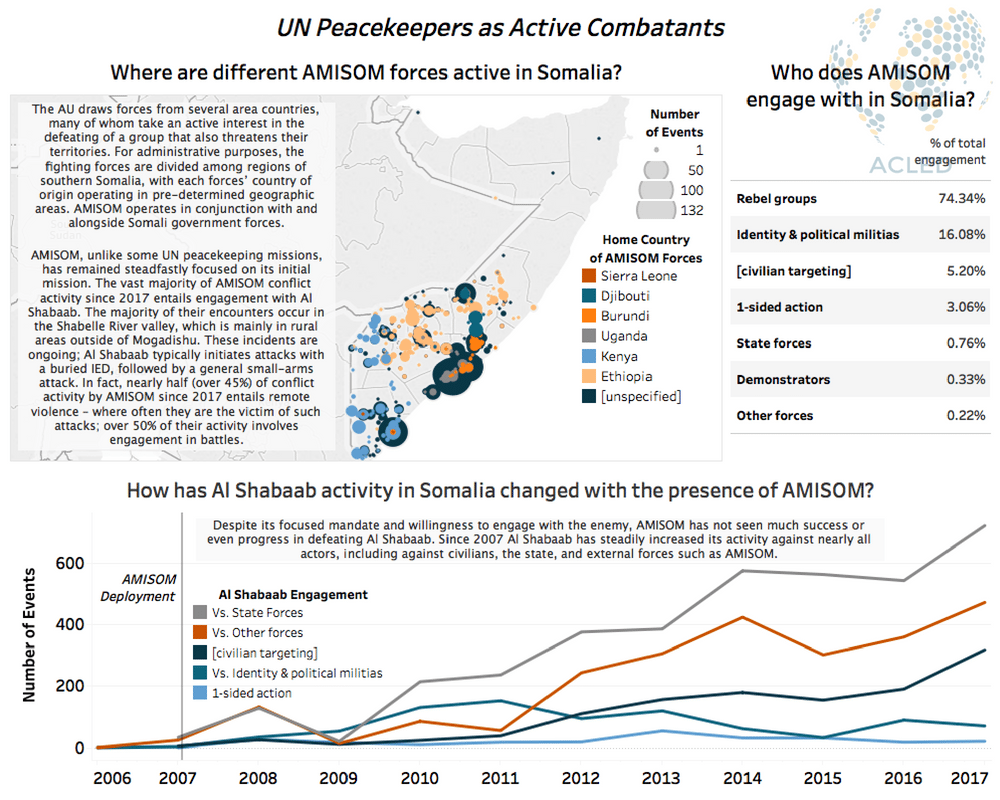

In these types of peacekeeping missions, there is a mandate of addressing a specific, named threat. These missions will often require active engagement in violent conflict against a particular conflict actor. A prime example of this type of mission is AMISOM, the African Union Mission in Somalia.

AMISOM is at once the longest-lasting mission of the five mentioned above, and also the country with the largest number of deployed personnel. Its mission, consistent from the start of its 11-year active period, has been to defeat Al Shabaab (the Al Qaeda affiliate in the Horn of Africa) and to prepare the Somali military to be able to combat Al Shabaab on its own. The peacekeeping mission in Somalia is operated by the African Union (AU), with the approval of the United Nations (UN).

Recent proposals to withdraw and gradually transition AMISOM’s responsibilities to the Somali government have been met with concerns. Despite 11 years of combating the threat of Al Shabaab, Somalia remains unable to tackle this problem to the world’s (and its neighbors’) satisfaction.

- Broad Goals & Shifting Challenges

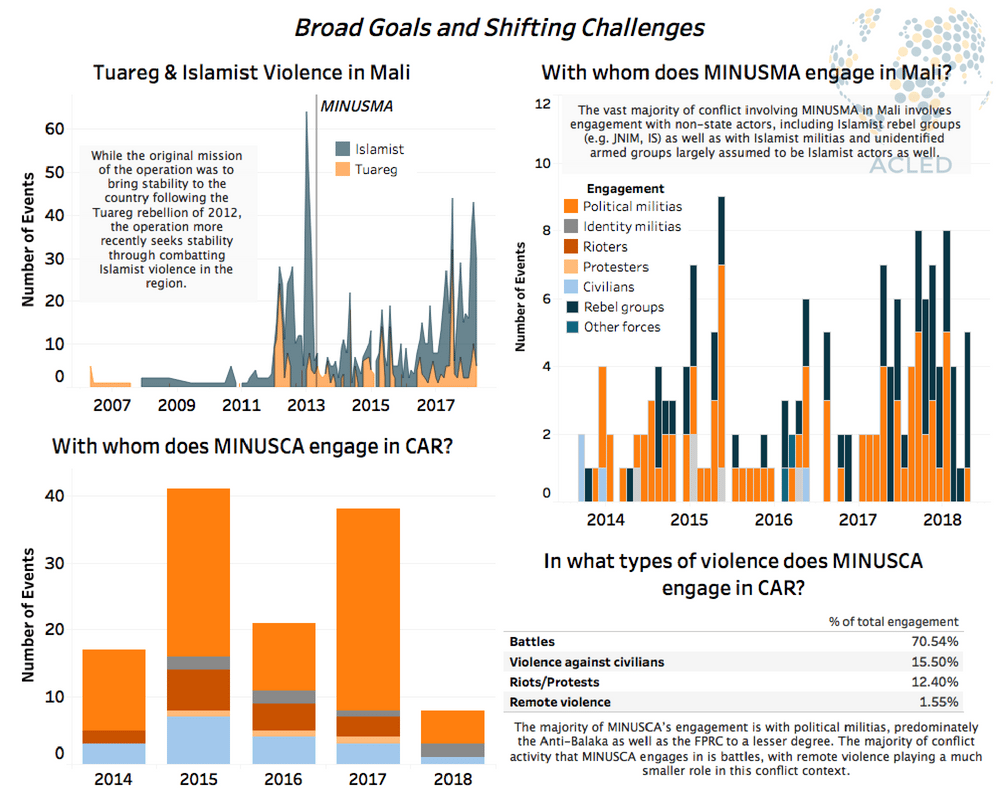

Not all missions have mandates as specific as AMISOM’s. Some peacekeeping missions have a mandate concerning broad threats to peace and stability, which may change over time. These missions have ongoing mandates that involve peacekeeping generally. Such mandates are often vague regarding the specific actors or groups with which the mission should engage. In some places, this flexible approach has resulted in these missions changing their focus over time.

In Mali, for example, the peacekeeping mission MINUSMA (The United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali) is active since 2013. But its mandate has changed as the primary threats to Mali’s security have evolved. Similarly, MINUSCA, the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (CAR), operates on a number of different fronts, under a broad mandate of protecting civilians.

The multi-faceted challenges facing these missions have resulted in highly dangerous situations for personnel involved with these UN missions, who face threats from multiple fronts. In Mali, the MINSUMA mission is dangerous for peacekeepers; approximately two thirds (65%) of conflict activity involving MINUSMA is remote violence, with peacekeepers often the victims of IED attacks. Approximately one-third (35%) of MINUSMA activity involves engagement in battles. The lethality of events in which MINUSMA is engaged has been increasing since 2017, with a spike in lethality in March.

In 2017-2018, UN troops in CAR also witnessed a high number of attacks in the prefectures of Haut-Mbomou, Ouaka, Basse-Kotto, Haute-Kotto, and in Bangui, notably in the KM5 neighborhood. More recently, the lethality of conflict events involving MINUSCA has spiked in April.

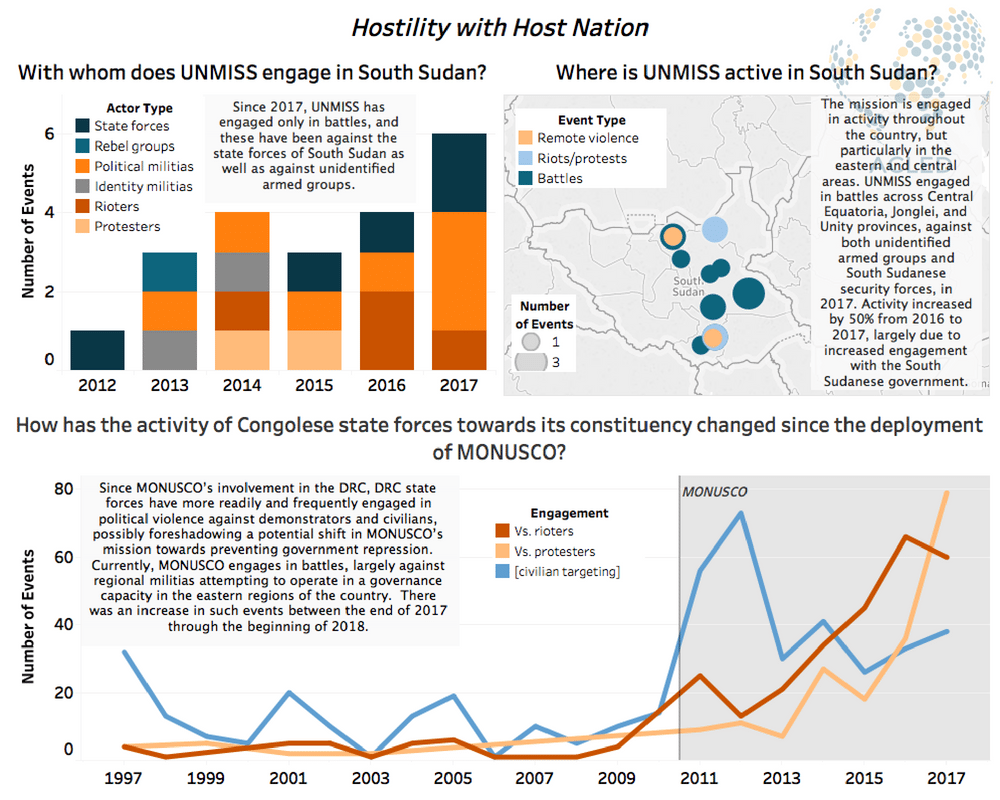

- Hostility with Host Nation

Even more precariously positioned are UN peacekeeping missions which actively working against the government of the state in which they operate. These are missions with a mandate to address the host state itself. These missions directly engage with the host nation or its proxy forces, sometimes violently. UNMISS, the United Nations Mission in South Sudan, has been present in the country since its independence in 2011. The UN Security Council (UNSC) recently renewed its mandate, a decision that the Government of South Sudan protested, because the “government was not consulted” and the Council “had chosen to politicize a peacekeeping resolution”.

Similarly, the UN’s stabilization mission in the DRC (MONUSCO in its current form) has a challenging and changing relationship with the government of the DRC. The mission has been active in the country since 2010. Its mandate was renewed on 27 March 2018, and (newly) included a specific clause directed at the protection of free and fair elections. Prior to the renewal of the mandate, a number of protests took place outside of UN offices, calling for the addition of this elections clause. This is possibly a measure preparing for the presidential elections in December 2018, which have been postponed by President Kabila. MONUSCO is largely active on the DRC’s eastern border with Uganda and Tanzania, particularly in its North and South Kivu provinces.

Conclusion

The varying approaches to peacekeeping outlined above – violent engagement with a particular actor, wide-ranging engagements against ever-changing threats, or political pressure directed at the host nation — clearly demonstrate that not all peacekeeping missions in Africa are the same. They vary not only in scope, size, and mission, but also in the type of activity in which they engage, the conflict actors with whom they interact, and how the mission’s mandate manifests on the ground. These differences, despite all missions being governed by common principles, have real and variable consequences in each country concerned.

[1] While the AMISOM mission in Somalia is included here, it is technically operated by the African Union with the UN’s approval.

[2] https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/mission/minusma

[3]http://amisom-au.org/; https://theglobalobservatory.org/2017/01/amisom-african-union-peacekeeping-financing/; https://theglobalobservatory.org/2015/09/amisom-african-union-somalia-peacekeeping/ https://theglobalobservatory.org/2015/09/amisom-african-union-somalia-peacekeeping/

[4] https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/mission/minusca

[5] https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/mission/unmiss

[6] https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/mission/monusco