Our annual special report reviews the past year of data for 10 key conflicts with a look toward trends to watch in the coming months. Access ACLED data directly through the export tool, and find more information about ACLED methodology in our Resource Library.

To explore an interactive visualization of this special report, click here.

In 2019, the world witnessed a drastic increase in violent disorder that assumed many forms: protests from Lebanon to Hong Kong and Iraq to Chile; geopolitical competition in Yemen and Syria; dominant insurgencies in Somalia and Afghanistan; a cartel-insurgency in Mexico; and a diffuse, adaptable militant threat across the Sahel. Two problems immediately stand out: the world is significantly more violent now than a decade ago, and today’s conflict forms are strongly localized — types of violence, agents, targets, and solutions are unique to their local context. This is partially because governments in the world’s most violent places are no longer in control of their territories, nor show any interest or ability to resume control through direct or indirect authority. Governments are also much more likely to use violence against their citizens without international reproach. The rise of authoritarianism — and impunity — has generated significant public reaction in the form of mass protest movements, but it has also increased the level of violence imposed upon civilians and political competition.

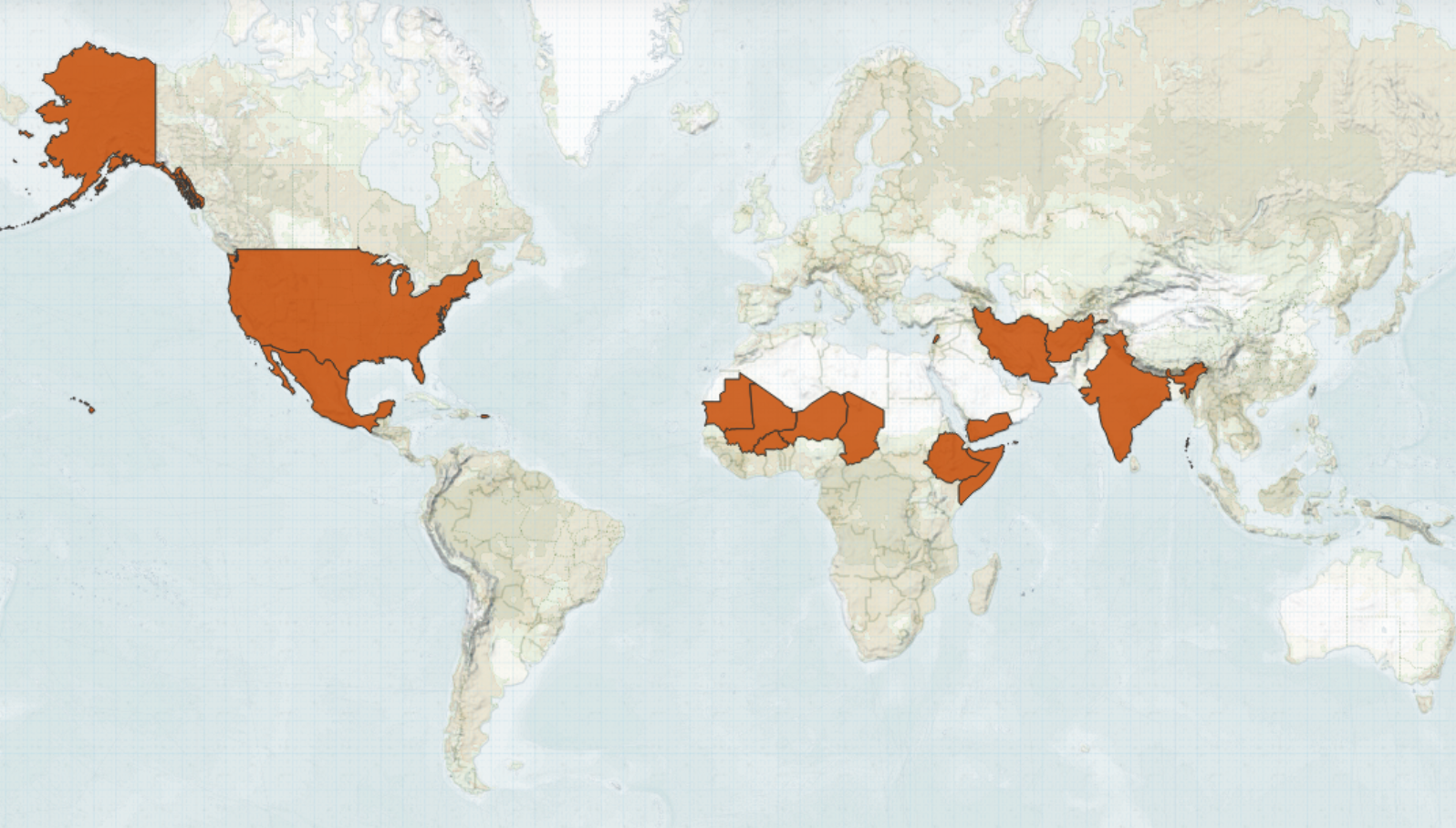

In this report, ACLED has chosen 10 conflicts that demonstrate how violent political disorder is evolving in places it has festered for decades — such as Afghanistan — as well as in relatively new spaces — such as the United States. Across these 10 cases, observers have often concentrated on active threats and acts of violence, and less so on the latent risks that may produce new agents, modalities, targets, and opportunities for violence. If the past decade offers any lessons, it is that conflict can take many forms, and can arise from a range of local vulnerabilities if stoked. Here, we review 10 situations in which conflict is likely to change and worsen in the coming year, creating new dilemmas for governments and citizens.

10 Conflicts to Worry About in 2020

Please click through the drop-down menu below to jump to specific cases.

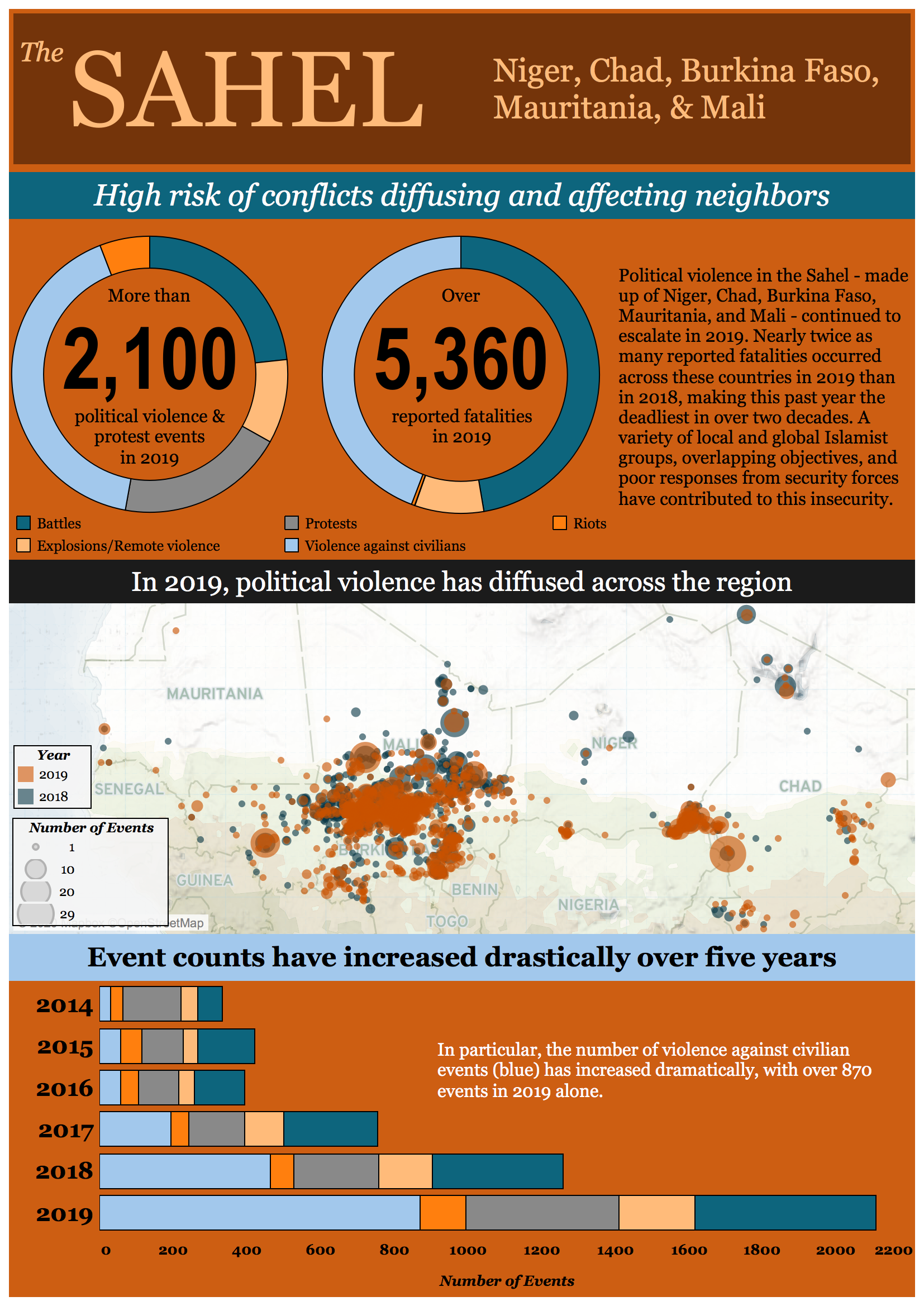

High risk of conflicts diffusing and infecting neighbors

Last year, ACLED assessed that the Sahel was “most likely to be the geopolitical dilemma of 2019.” The Sahel now hosts more multiple, moving threats than it did in 2018: Nigeria’s Boko Haram has become a regional threat; Cameroon’s north is beset by cross-border violence; Chad is beginning to experience insurgency attempts in several uncoordinated spaces; Niger’s Tillaberi region – once able to stay the pressure from its borders – is now within the sights of an IS affiliate (Al Jazeera, 22 September 2019); and Burkina Faso is engulfed in conflict across all regions, as groups from Mali continue their southern encroachment. The latter three states host the worst violence: violence rates in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger doubled in 2019 compared to 2018.

The growing threat posed by Islamist militant groups has attracted a number of foreign powers, with intersecting deployments of French, American, African, and EU troops all present in the region — adding to an already complex security situation. Still, the most serious and destabilizing acts of violence are perpetrated by local militias, recruited by or possibly partnered with either Jihadist organizations or domestic governments. These dynamic arrangements are actively reconfiguring the political geography of states at a time when ideologies and alliances are in flux across the Sahel.

While the Sahel crisis has been strongly cast as an African example of the global Jihadi threat, the most recent surge in violence underscores that local, domestic, often ethnicized tensions generate and perpetuate the most lasting instability. But it also has important lessons about how groups change and evolve to foster their adaptation in new environments and circumstances: those groups have diffused through taking advantage of the local authority and political competitions that have beset northern Mali, Burkina Faso since 2012, and, increasingly, Niger.

What to watch for in 2020:

Yet, there is no doubt that the conflicts in the Sahel are increasingly inter-related despite the overtly local nature of alliance-making. At the local level, ethnic identities exploited to foster insurgency can be linked across different states — such as the Fulani in Nigeria, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, as well as the Dogon across Mali and Burkina Faso. In Burkina Faso, the fight between militants and Koglweogo — including Mossi, Foulse, Gourmantché, and others depending on the region — is central to the current conflict, which is continuously mutating and fast becoming more brutal. Across the region, active militant groups are rapidly transforming from cell/matrix-based and midsize organizations into a mass insurgency.

All states in the Sahel are linked in the possibility that internal risks will create opportunities for distraction and overextension of state and international security agents, and collaboration of domestic armed groups with external, bordering threats.The region’s metastasizing militant networks are generating opportunities for training, arms trafficking, and recruitment across porous borders, exposing the vulnerabilities of Sahelian states like Chad and the western regions of the Central African Republic. It is these latent conflicts that tend to be ignored and poorly understood, but increased infiltration will make an enormous difference in how risk may move beyond the Sahel. Based on the current trajectory of the moving groups, the most immediate threats are centered on northern Cote D’Ivoire — where a contentious election in 2020 is exposing old political faultlines; northern Ghana — where a recent history of ethnic preferences in land law and tax disputes has pit Fulani and other citizens against each other; southern Mali — where the national government has largely ignored or poorly reacted to the encroachment of a northern threat; and Guinea — where disputes about constitutional term limits are distracting the government and emboldening those in opposition to the Conde regime.

Further reading:

- Explosive Developments: The Growing Threat of IEDs in Western Niger

- Democracy Delayed: Parliamentary Elections and Insecurity in Mali

- A Vicious Cycle: The Reactionary Nature of Militant Attacks in Burkina Faso and Mali

- Heeding the Call: Sahelian militants answer Islamic State leader al-Baghdadi’s call to arms with a series of attacks in Niger

- No Home Field Advantage: The Expansion of Boko Haram’s Activity Outside of Nigeria in 2019

- JNIM: A Rising Threat to Stability in the Sahel

- The New Normal: Continuity and Boko Haram’s Violence in North East Nigeria

- Insecurity in Southwestern Burkina Faso in the Context of an Expanding Insurgency

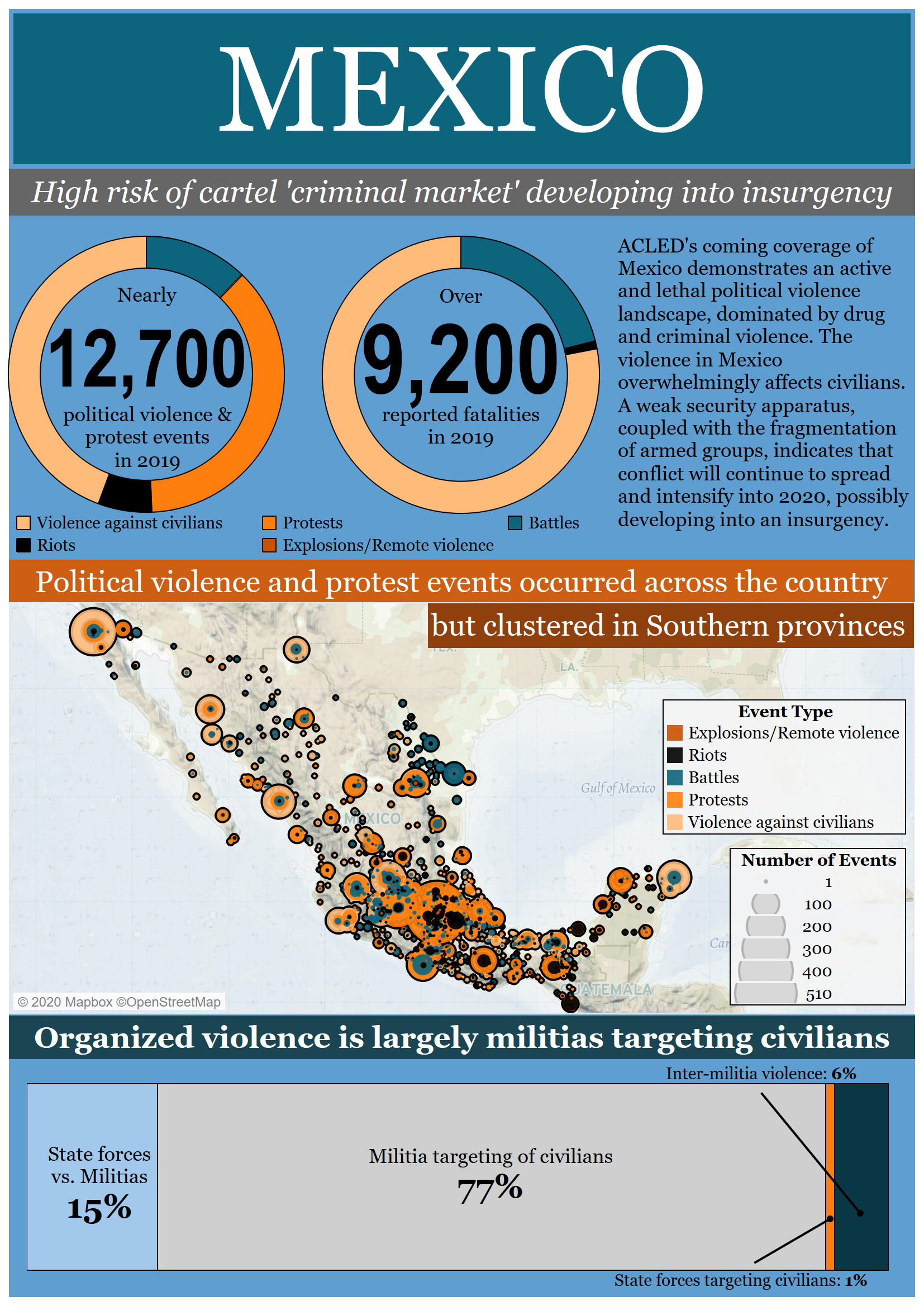

High risk of cartel ‘criminal market’ developing into insurgency

Mexico is facing a deteriorating security situation and continues to experience unprecedented levels of criminal and drug-related violence. 2019 has registered a record number of homicides yet again, after 2017 and 2018 broke previous records: over 31,000 homicides were recorded nationwide over the past 12 months, and the government just released data indicating over 60,000 people have disappeared since 2006. Besides inter- and intra-organizational tensions, there is an increasing diversification in violent street crime affecting Mexican civilians on a daily basis, posing a major challenge to public safety and security. The vast majority of events involving gangs recorded by ACLED in 2019 were instances of violence against civilians.

While the killings of journalists and government officials, beheadings, disappearances, and public hangings of corpses recurrently make headlines in Mexico, several particularly brutal attacks have raised concerns that the cartels are increasingly adopting insurgent techniques. In October 2019, an operation to capture the son of drug kingpin Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán in the city of Culiacan led to an intense 12-hour gun battle between the Sinaloa cartel and the Mexican security forces, prompting the federal government to release Ovidio Guzmán to avoid further escalation. That same month, two further gunfights between security forces and armed groups erupted in the state of Guerrero and Michoacán, reportedly killing 28 people. In November, a cartel ambush killed 10 Mexican-American Mormon women and children. The attack led US President Donald Trump to announce that Mexican drug cartels would be designated as terrorist groups, though the plan was later put on hold. And lastly, near the US border in the state of Coahuila, a cartel launched a military-style invasion into Villa Union, leading to an hours-long gun battle with state and federal forces at the beginning of December, leaving 22 people dead.

In addition to high levels of impunity, untrained security forces, and the general weakness of public institutions in Mexico, the escalation of violence can be partially attributed to the fragmentation of cartels caused by law enforcement campaigns primarily targeting their leaders, an approach that was initiated during the so-called “war on drugs” declared by former President Felipe Calderon in 2006. With arrests of almost exclusively cartel leaders, the previously monolithic criminal groups were split up, increasing the number of cartels from six to as many as 37 (El Economista, 19 May 2019). The splinter groups are competing violently over the existing drug trade infrastructure, but are also constantly evolving and diversifying criminal activities by engaging in kidnapping, extortion, fuel theft, and human trafficking.

By some accounts, another factor contributing to the increase of violence is the recent shift in power. The inauguration of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador on 1 December 2018 brought an end to institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) rule, which dominated Mexican politics for much of the 20th century. Political turnover may correlate with increased rates of violence, as standing modes of coexistence between public officials and criminal groups are undermined, spurring uncertainty amid a struggle for new arrangements (Trejo and Ley, 2 August 2017).

The deteriorating security situation also generated protest activity throughout the country, with demonstrations organized by human rights groups, feminist activists, and families of disappeared persons calling for justice and an end to the violence. In August, allegations of police officers raping and sexually abusing women led to a demonstration movement that has become known as the “glitter protests.”

What to watch for in 2020:

Incidents like the retaliatory attack by the Sinaloa cartel following the arrest of El Chapo’s son raise fears that the cartels may appear stronger than the military (Time, 18 October 2019). Critics argue that President López Obrador has been unable to develop a coherent and effective security policy to fight cartel-related violence. The president tasked the newly formed National Guard – composed of military and federal forces, as well as new recruits – with addressing the problem, thereby prolonging the formerly unsuccessful militarization of the security situation. Structural violence requires long-term solutions, such as strengthening the police, justice, and prison systems. Mexico is confronted with an increasingly complex, fragmented, and multipolar criminal market and a resolution to these structural problems is unlikely in the short-term, raising the possibility of intensified conflict in the new year. It is expected that, in 2020, brutal everyday violence will continue unabated, and homicide rates will break records once again.

Data on political violence and protest activity in Latin America and the Caribbean will be published in February 2020, at which point ACLED will begin releasing weekly real-time data updates for the region. Subscribe to our mailing list to receive the launch announcement or contact us for more information.

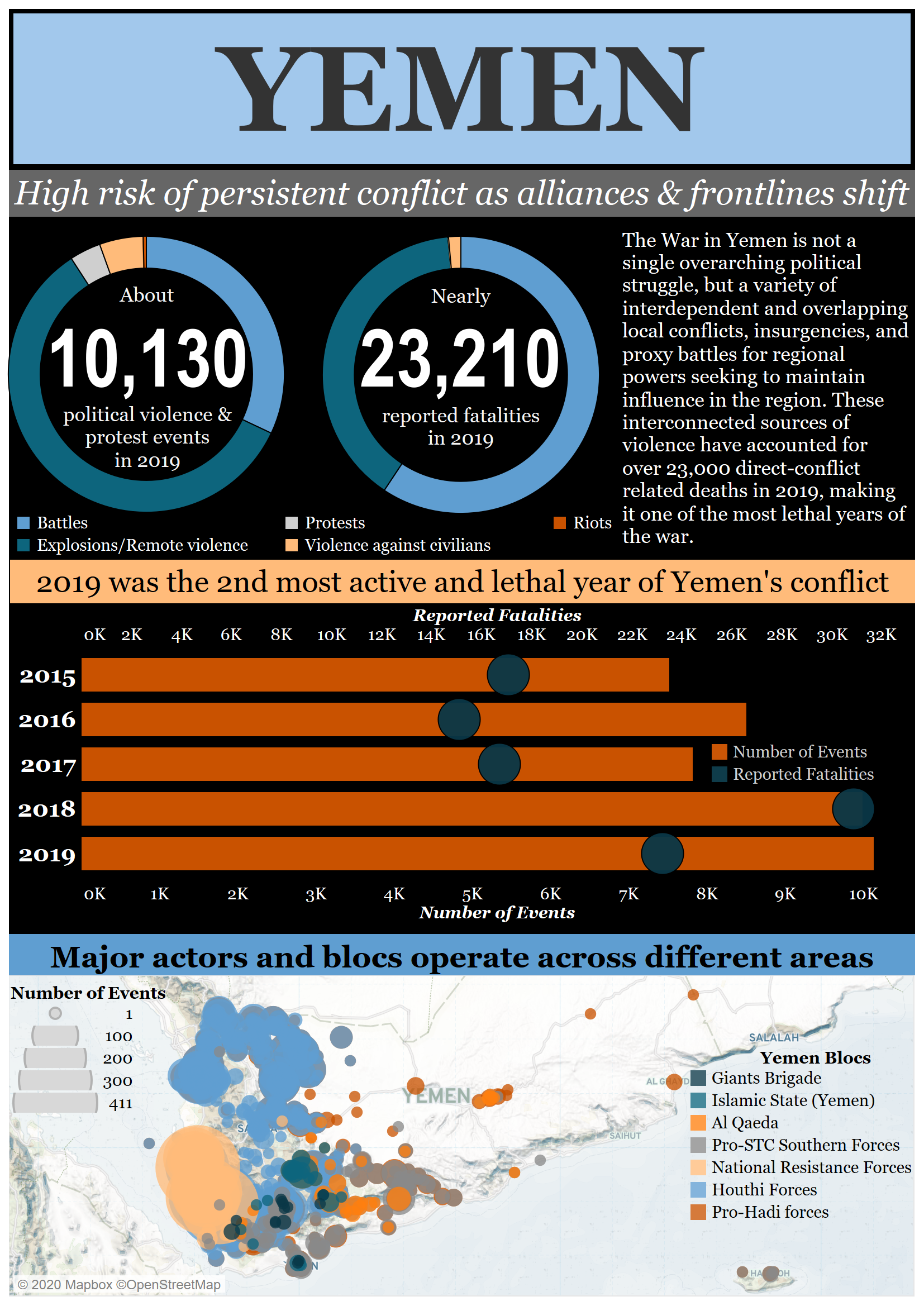

High risk of persistent conflict amid shifting frontlines and alliances

Five years into the conflict, the scale of destruction in Yemen has reached unprecedented levels: more than 100,000 people are estimated to have died as a direct result of the violence, including over 12,000 civilians killed in targeted attacks. ACLED records over 23,000 deaths in 2019 stemming directly from the conflict — a 25% decrease in total reported fatalities from 2018, but still the second deadliest year of the war.

The war in Yemen consists of a variety of interconnected local conflicts involving regional powers competing for influence. The first of these conflicts pits the Houthis — a Zaydi revivalist movement hailing from Yemen’s northern highlands that seized the capital Sana’a in 2014 — against the internationally recognized government, led by President Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi. Hadi enjoys the support of Saudi Arabia which, together with allies like the UAE, launched a military intervention in support of the government in March 2015 in order to prevent the Houthis from overtaking the southern port city of Aden.

The second conflict is linked to the secessionist Southern Transitional Council (STC), a political organization established in May 2017 that advocates for the creation of an independent state in southern Yemen. The STC has extended its influence across Yemen’s southern governorate through a vast network of Emirati-backed militias, some of which are fighting against the Houthis in Ad Dali and, increasingly, against Hadi loyalists in several southern governorates. In Hodeidah province, a different network of Emirati-backed militias under the umbrella of the National Resistance Forces (NRF) has emerged. These forces are made up of three major components, the Guardians of the Republic led by the former President’s nephew Tariq Saleh, the Salafist Giants Brigade, and the Tihami Resistance. The Guardians of the Republic tend towards maintaining their independent status without any clear allegiance to either the STC or Hadi loyalists, while the Giants Brigade has become an ally of the STC in fighting in Ad Dali, Taizz, and Aden, as Hodeidah has seen a drastic decrease in clashes over the last year.

The third main conflict is an Islamist insurgency launched by Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and the Yemeni branch of the Islamic State (IS). Both groups currently possess limited operational capacities in the country and continuously clash with each other over influence in the Qayfa area that stretches over Al Bayda province, where the two jihadi organizations have been waging a “hit-and-run war” for the past 20 months (Sanaa Center, 14 October 2019). Houthi forces, Hadi loyalists and pro-STC forces are targeted sporadically mainly through IED and suicide attacks in Aden, Abyan, and Marib governorates.

The first conflict between the Houthis and anti-Houthi forces decreased in intensity as the UN-brokered Stockholm Agreement bore some fruit in 2019, leading to a dramatic decline in clashes and fatalities in and around the key port city of Hodeidah. Artillery shelling, however, continued daily in violation of the tenuous agreement. Nevertheless, the international commitment has avoided further offensives by the National Resistance Forces on the western front as they seem to fear damage to their fragile reputation. Meanwhile, clashes over territory in Ad Dali, Sadah, and Hajjah governorates continued between both sides, with Houthi forces losing control over major strategic crossroads in Ad Dali.

The most significant development last year was the breakdown of the delicate balance between the STC and Hadi government forces in Aden, Abyan, and Shabwah governorates in August. For Aden, August 2019 was the most violent month of the conflict since the height of the fighting with Houthi-Saleh forces in 2015. Frontlines stabilised after about a month, and efforts were undertaken to solve the conflict and unify ranks against Houthi forces. This development took place in conjunction with a withdrawal of Emirati forces from several southern governorates and a step-by-step handover of responsibility on the “southern question” to Saudi Arabia. STC-affiliated forces and pro-Hadi government forces signed the so-called Riyadh Agreement under the custody of Saudi Arabia in November. The plan calls for both sides to unify under a new government and to restructure the security sector, but it has yet to be implemented as clashes have continued. In early January 2020, the STC announced its withdrawal from the agreement’s implementing committees (Reuters, 5 January 2020). In all southern governorates, successes in implementing the Riyadh Agreement will be crucial in determining future patterns of violence. The current breakdown of the balance between the two sides could lead to an escalation of conflict across the region, albeit with different trajectories, as the STC has become an active player with different capabilities in all of the southern governorates.

What to watch for in 2020:

Like 2019, the new year is already being met with a mixture of hope and skepticism over the prospects for peace in Yemen. Indirect negotiations between Saudi Arabia and the Houthis in Oman, prisoner exchanges, and the reopening of Sana’a international airport for humanitarian and medical purposes represent renewed attempts to break the cycle of violence after the UN-backed Stockholm Agreement, which led to a significant drop in violence in Hodeidah. Success in current negotiations could lead to a significant decrease in the Saudi war effort. Saudi disengagement will also affect the trajectory of the civil war in Yemen. Nevertheless, as long as the different Yemeni sides to the war do not come to an agreement between themselves, physical violence will continue.

In the same vein, the apparent failure of the Riyadh Agreement to solve the southern issue seems to pit southern secessionists further and further against the Hadi government, resulting in the de facto establishment of a minimized southern state under the control of the STC in Aden, Lahij, and some parts of Abyan, Ad Dali, and Shabwah. The ultimate success or failure of the indirect negotiations between Saudi Arabia and the Houthis on the one hand, and the Riyadh Agreement on the other, will be critical for the future of the war in Yemen in 2020.

Further reading:

- Yemen’s Fractured South: ACLED’s Three-Part Series

- Inside Ibb: A Hotbed of Infighting in Houthi-Controlled Yemen

- Yemen Snapshots: 2015-2019

- How Houthi-Planted Mines are Killing Civilians in Yemen

- Yemen’s Urban Battlegrounds: Violence and Politics in Sana’a, Aden, Ta’izz and Hodeidah

- ACLED Methodology and Coding Decisions around the Yemen Civil War

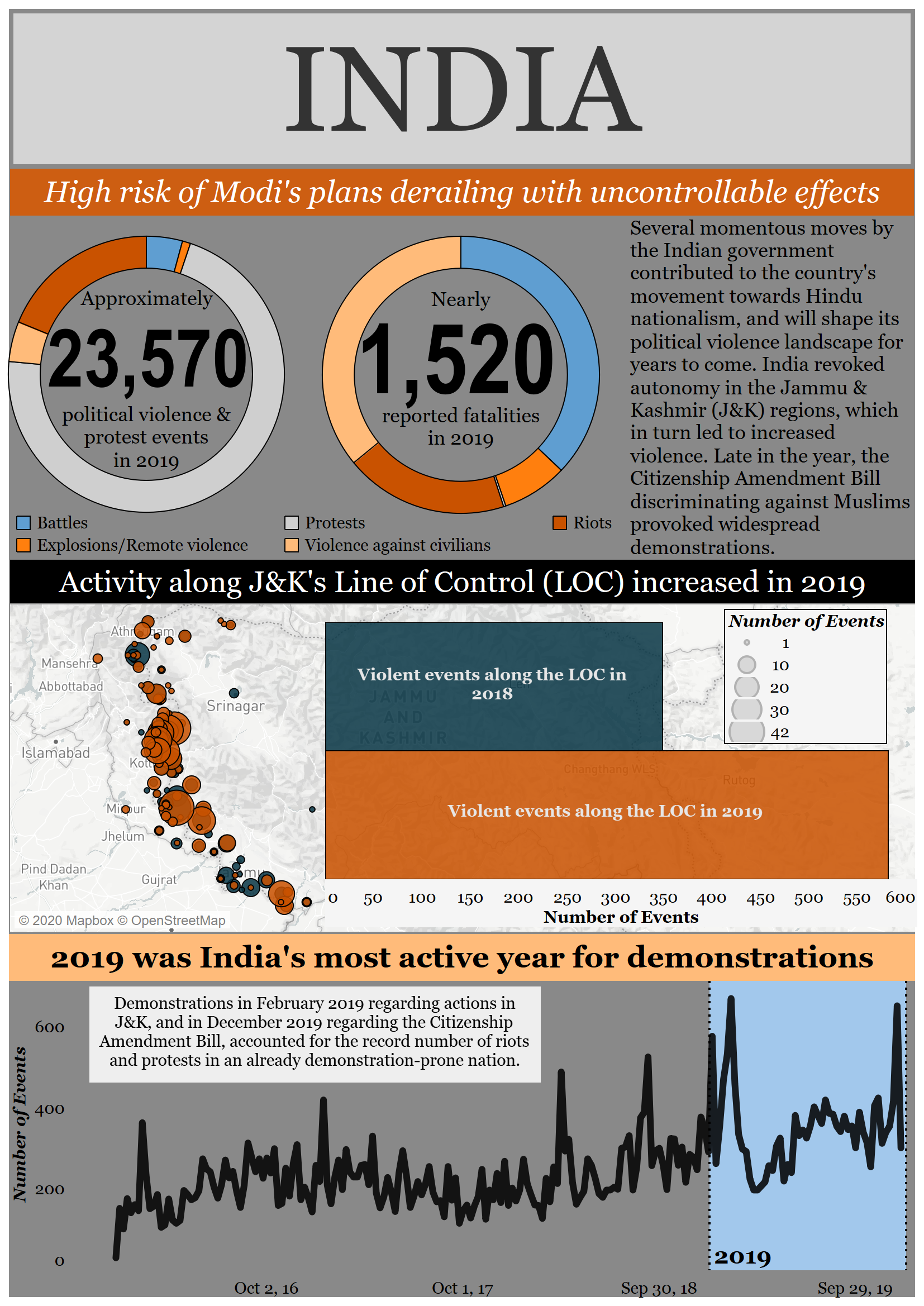

At risk of Modi’s plans derailing with uncontrollable effects

India’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led government is navigating a complex landscape of political discord involving long-standing international and domestic conflicts. Internationally, tension between India and Pakistan over the disputed Kashmir region escalated in 2019, as the volatile political relationship between the two countries was tested by militant attacks and frequent cross-border violence along the Line of Control (LoC). The imposition of strict security and communications restrictions in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) further strained relations with Pakistan and contributed to significant unrest within India. Internally, rising agitation against a controversial legislative measure sparked violence as the bill was eventually ratified as the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 (CAA). The CAA is criticized by some for being exclusionary toward Muslims. Others in India’s ethnically diverse northeast are opposed to the Act’s demographic ramifications, precipitating the threat of ethnic violence in the region. In central, eastern, and southern India, the ongoing Naxal-Maoist insurgency persistently threatens to subvert government authority and democratic processes in the region. Additionally, violent inter-party rivalries extend the schism between the numerous concurrent political ideologies which exist within the world’s largest democracy.

In February 2019, a Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM) militant launched a suicide attack on India’s Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) in Pulwama district of J&K, reportedly killing at least 37 CRPF troopers. Following the Pulwama attack, Indian fighter jets launched strikes on militant targets in Pakistan. Pakistani forces responded by sending a sortie into Indian airspace and reportedly dropping bombs in J&K’s Poonch and Rajouri districts. These incidents culminated in an aerial battle between Indian and Pakistani forces, resulting in the downing of two aircraft in Pakistani territory, as well as the arrest of an Indian pilot by Pakistani troops. Pakistan’s return of the detained Indian pilot did little to de-escalate the conflict.

Tension in the Kashmir region was again aggravated in August 2019, prior to the J&K Block Development Council (BDC) elections, when the Indian government issued a presidential order abrogating articles 370 and 35 A of the constitution, thereby revoking autonomy for J&K, India’s only Muslim-majority state. The state of J&K, which had its own constitution and freedom to formulate its own laws, was reduced to a union-territory under the administration of New Delhi. Tens of thousands of troops were moved into the region (India Today, 2 August 2019), political leaders were placed under house arrest (Al Jazeera, 17 August 2019), and severe communications restrictions were imposed.

The events in J&K further soured India-Pakistan relations: in his speech at the UN General Assembly on 28 September 2019, Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan criticized the Indian government’s perceived anti-Muslim agenda and alleged human rights violations in Kashmir. He also stated that Pakistan would not back down from conflict with India (Business Recorder, 27 September 2019). ACLED records a significant increase in violent events across the LoC between Indian and Pakistani security forces in 2019 compared to previous years: 582 cross-border shelling and firing events were reported in 2019, compared to 349 in 2018. Cross-border violence in Kashmir led to nearly 180 reported fatalities during the year. Additionally, on call from the Pakistani government, nationwide anti-India demonstrations and Kashmir solidarity rallies were held in Pakistan throughout the end of 2019.

In October 2019, BDC elections proceeded in J&K amidst the ongoing controversy, raising questions about the legitimacy of the political process (Hindustan Times, 30 September 2019). Major opposition parties boycotted the elections citing detention of party leadership and security restrictions preventing their participation in political activities leading to the elections. Despite India’s ruling BJP having the freedom to campaign across J&K and contest unopposed by the state’s mainstream political establishment, independent candidates unexpectedly took 19 of 22 J&K districts at the polls (The Wire, 26 October 2019). The BDC election results were indicative of the growing dissociation between Kashmiri citizens and the BJP. Furthermore, strong opposition to the Indian government’s actions in J&K were reported across the country in the form of protests, violent demonstrations, and clashes with police forces.

In addition to opposition within India to the situation in J&K, dissent against the CAA surged during the final quarter of 2019. Opponents of the law argue that it discriminates against Muslims (The Guardian, 13 December 2019), as it grants citizenship rights to undocumented non-Muslim immigrants, explicitly precluding citizenship rights for Muslim migrants. Other critics in India’s northeast contend that legitimizing undocumented immigrants would threaten the indigenous communities of the region. The northeastern region, which is home to a culturally and ethnically diverse population, remains somewhat excluded from the national mainstream and has a history of insurgent and secessionist activity. As the region is a focal point of immigration from Bangladesh, issues regarding immigration policy have been a continued source of conflict between the indigenous and immigrant populations. In late 2018, five Bengali Hindus were reportedly killed by militants in Assam. During the same time period, a leader of a faction of the United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA), a militant separatist group in Assam state, threatened a “massacre” of Bengali Hindus (Northeast Now, 26 October 2018) as a consequence of the passage of the CAA.

The eventual passage of the CAA on 19 December sparked violent demonstrations and clashes with police across the country, with at least 18 people reported killed as of 4 January 2020. Alarmingly, ruling BJP leaders admitted that the government did not anticipate the enormous backlash against the passage of the CAA beyond limited unrest among the Muslim community (US News, 25 December 2019). Such revelations from senior party leadership seem to be indicative of the myopic nature of the BJP’s popular Hindu nationalist/anti-Muslim posturing.

What to watch for in 2020:

Heightened tension between India and Pakistan surrounding the Kashmir issue, coupled with dissent against the perceived anti-Muslim nature of the Indian government’s policies surrounding Kashmir and the CAA, will perpetuate the environment of mistrust between Islamabad and New Delhi. Pakistan has recently adhered to a policy of vocal opposition to India. Mass demonstrations over the Kashmir issue and against the CAA are routinely organized within Pakistan, and Pakistani leaders have criticized Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s tactics at international forums such as the UN General Assembly. With the ever-present threat of another militant attack looming over J&K, and the Indian government’s stance on Pakistan as a militant safe haven (BBC, 1 May 2019), 2020 is expected to be a perilous year for the future of India-Pakistan relations.

Citizens of J&K ended 2019 with a reduced right to self-determination, suppressed civil liberties and roadblocks to democracy following constitutional and security measures introduced prior to BDC elections. Although the Indian government has taken steps to scale back communication and security restrictions in Muslim-majority J&K, its policy towards India’s Kashmiri citizens has created more friction within an already tense relationship. Furthermore, such policies have amplified existing hostility between Kashmiri citizens and Indian security forces surrounding a history of ongoing human rights abuses in the region (Human Rights Watch, 10 July 2019). Violence between Indian security forces and Kashmiri locals could intensify in the coming year if the government neglects to take definitive action to curb human rights violations by security forces. Additionally, the continuing alienation of India’s Kashmiri Muslims from the mainstream could potentially contribute towards increased support for militancy, as well as violence between Muslim and Hindu communities in the region.

The recent passage of the CAA threatens to generate continuing violence between demonstrators and police, as well as violence between left-wing opponents and right-wing supporters of the law across India. Immigrant communities are faced with potential backlash by indigenous communities in the northeast region, as well as the threat of mass violence by ULFA militants. Admissions that BJP leaders were blind-sided by outrage against the CAA raise concerns about their ability to anticipate violent scenarios and prevent them from materializing.

Elections for state legislative assemblies and the Rajya Sabha, the upper house of parliament, set for 2020 will be important gauges through which to assess the fallout faced by the BJP in the wake of the Kashmir and CAA controversy. State legislative assembly elections will be held in Delhi and Bihar. The BJP-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) hopes to make inroads in Delhi where they will face stiff opposition from the incumbent Aam Admi Party (AAP) and Indian National Congress (INC) as well as the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD)-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA). Similarly, In Bihar, the NDA will have to contend against UPA as well as the incumbent Janata Dal (United). Meanwhile, the outcome of the Rajya Sabha elections will be important in determining the extent of the BJP’s influence in parliament. Despite the BJP’s increased numbers in the Rajya Sabha post-2014, the opposition majority has hindered the BJP’s ability to pass controversial bills (Money Control, 1 January 2020). Additionally, pre-election campaigning in Bihar, as well as in states like West Bengal and Assam where legislative assembly elections are slated to be held in 2021, can be expected to produce more political violence. Naxal-Maoist conflict in Bihar, the historic violent political rivalry between the BJP and Trinamool Congress Party (TMC) in West Bengal, and retaliation against the unpopular CAA in Assam all present significant law and order challenges.

Growing instability going into 2020 necessitates a reevaluation of policies by the Indian government in order to tackle the proliferation of discontent and conflict across the country. It remains to be seen whether the ruling BJP will be willing or able to adopt a more pluralistic approach to address accumulating governance challenges. It seems likely that Prime Minister Modi’s current tactics will unravel across India’s vast political landscape.

Further reading:

- The Border Campaign: Pakistan-India Border Violence and the Indian Elections

- The Indian General Election 2019: A Final Recap

- Securing Democracy: Electoral Violence in India

- Blurring the Line of Control: How Indian Public Engagement has Shaped the Kashmir Conflict

- Citizenship Row: India’s Controversial Citizenship Amendment Bill, 2016

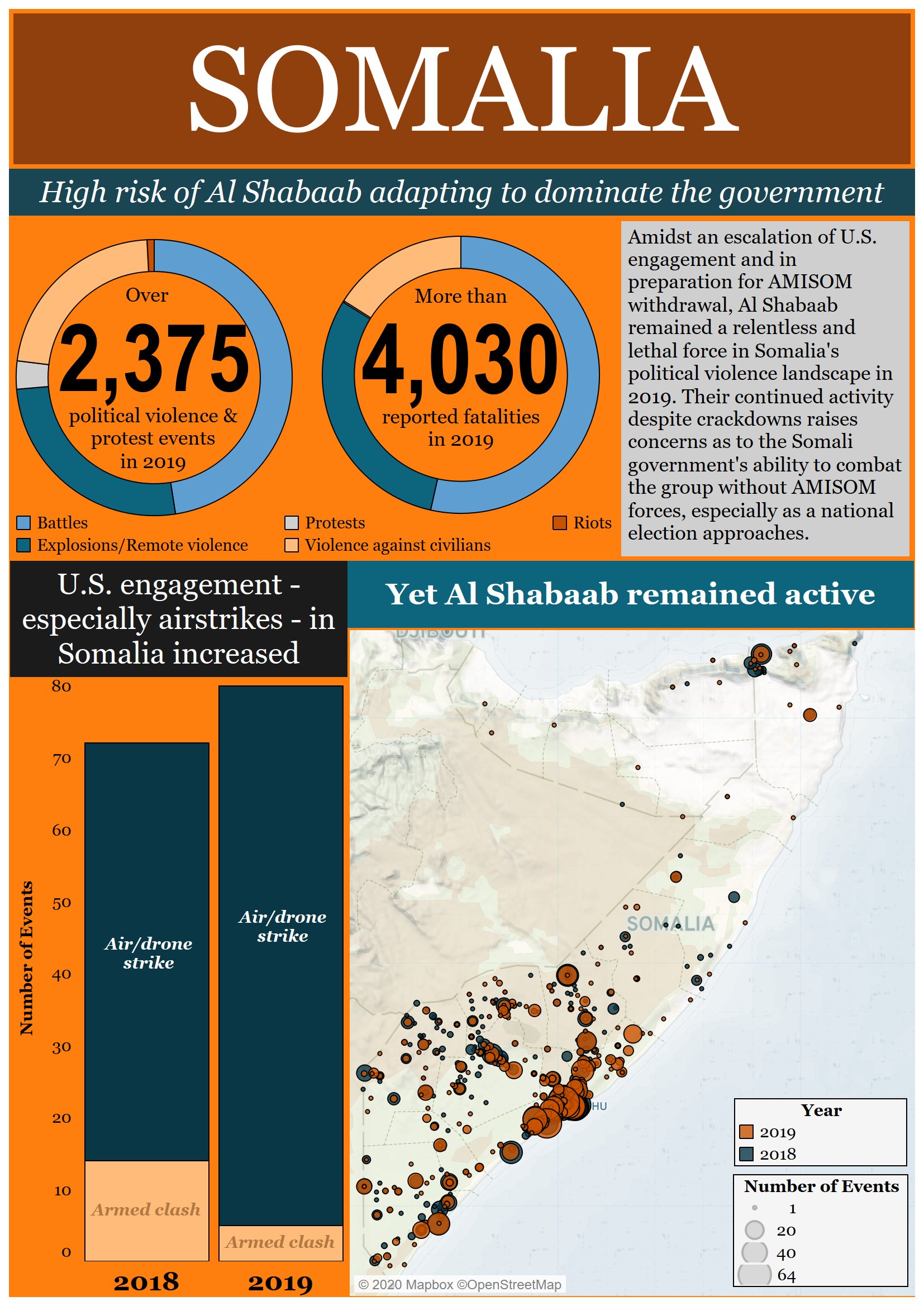

High risk of Al Shabaab adapting to dominate and isolate a weak government

Despite continued AMISOM operations and an increase in US airstrikes throughout 2019, Al Shabaab remains a major threat to Somali society and President Mohamed Abdullahi Farmajo’s government in 2020. As the country gears up for its first national election with universal suffrage since the outbreak of civil war in 1992, the ability to provide safety and effective governance are key to ensuring the legitimacy of the government. Unless cooperation among Somalia’s federal member states increases and the threat from Al Shabaab is more effectively neutralized, Somalia is likely to see continued obstacles to its recovery from collapse. Given aggressive attempts at influence by external actors, increased cooperation is far from likely and conflict could worsen during the coming year.

Somalia’s security partners in the fight against Al Shabaab made major efforts to degrade the group throughout the year. The US dramatically ramped up its engagement in Somalia, striking Al Shabaab targets at unprecedented rates. ACLED records 72 air or drone strikes conducted by American forces last year, marking a 24% increase from 2018 (58 strikes) and a nearly 200% increase when compared to strikes in 2016 (24 strikes). The US escalation is part of an effort to weaken Al Shabaab prior to the upcoming handover of security operations from AMISOM to the Somali armed forces. At least 1,000 AMISOM troops have already withdrawn, and Somali forces are scheduled to take the lead in the campaign against Al Shabaab in 2021 (UN, 31 May 2019).

Al Shabaab has remained resilient to increased military pressure, however, proving itself capable of both “geographic expansion and high lethality attacks.” The militant group intensified operations toward the end of 2019, including a bomb attack on a checkpoint in Mogadishu that killed 81 people (News24, 30 December 2019). Al Shabaab has also demonstrated its continued ability to launch sophisticated attacks on well-guarded targets, such as in a recent cross-border attack on the Manda Bay airfield in Kenya that resulted in the death of an American service member and two defense contractors (AFRICOM, 5 January 2020).

In addition to attacks on military and government targets, Al Shabaab remains the largest threat to civilians in the country, frequently targeting non-military sites and unarmed civil servants with assassinations and improvised explosives. According to ACLED data, Al Shabaab is responsible for 44% of reported fatalities that occur during events in which civilians are directly targeted in Somalia. Clan-based actors are responsible for 16% of reported fatalities linked to civilian targeting events, while state and police forces are responsible for 13%. The remaining fatalities occur at the hands of unidentified actors or external forces, such as AMISOM or the US military.

What to watch for in 2020:

The recent uptick in Al Shabaab operations against targets in both Somalia and Kenya is likely to continue into 2020, posing a major security challenge for the Somali national government and its partners as they seek legitimacy by providing safety and security. Failure to defeat increasingly sophisticated attacks on targets inside Mogadishu suggests that Somali military forces are not ready for an AMISOM withdrawal. Complicating the matter is a lack of effective cooperation between the central government and federal states, which has become “an obstacle to achieving important national priorities” (AP, 21 November 2019).

Somalia, along with other Gulf of Aden littoral states, has also become one of the “most vivid examples of potential destabilization brought by the Gulf rivalry” between Qatar and the other members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) (New York Times, 22 July 2019). While Qatar and its ally Turkey are important supporters of President Farmajo’s federal government, the UAE has pursued relations with Somaliland, effectively undermining the federal government’s authority (Global Risk Insights, 1 February 2019). Serious violence has yet to occur as a result of these relationships, but the political strain jeopardizes the future of an already fragile state.

Somalia is scheduled to hold universal suffrage national elections in 2020 or early 2021, which will be the first since the outbreak of the civil war in 1992. Al Shabaab is likely to renew attempts at de-legitimizing the Somali government through frequent attacks, and Somalia’s Gulf allies are equally likely to ramp up efforts at securing political sway ahead of the general election. The events of this year will have a tremendous impact on the future of the country, raising the stakes for all involved.

Further reading:

- Resilience: Al Shabaab Remains a Serious Threat

- Not with a Whimper but with a Bang: Al Shabaab’s Resilience and International Efforts Against the Rebels

- Continued Conflict: Updates on Iraq, Sri Lanka, and Somalia

- Same Tune, New Key: Al Shabaab Adapts in the Face of Increased Military Pressure

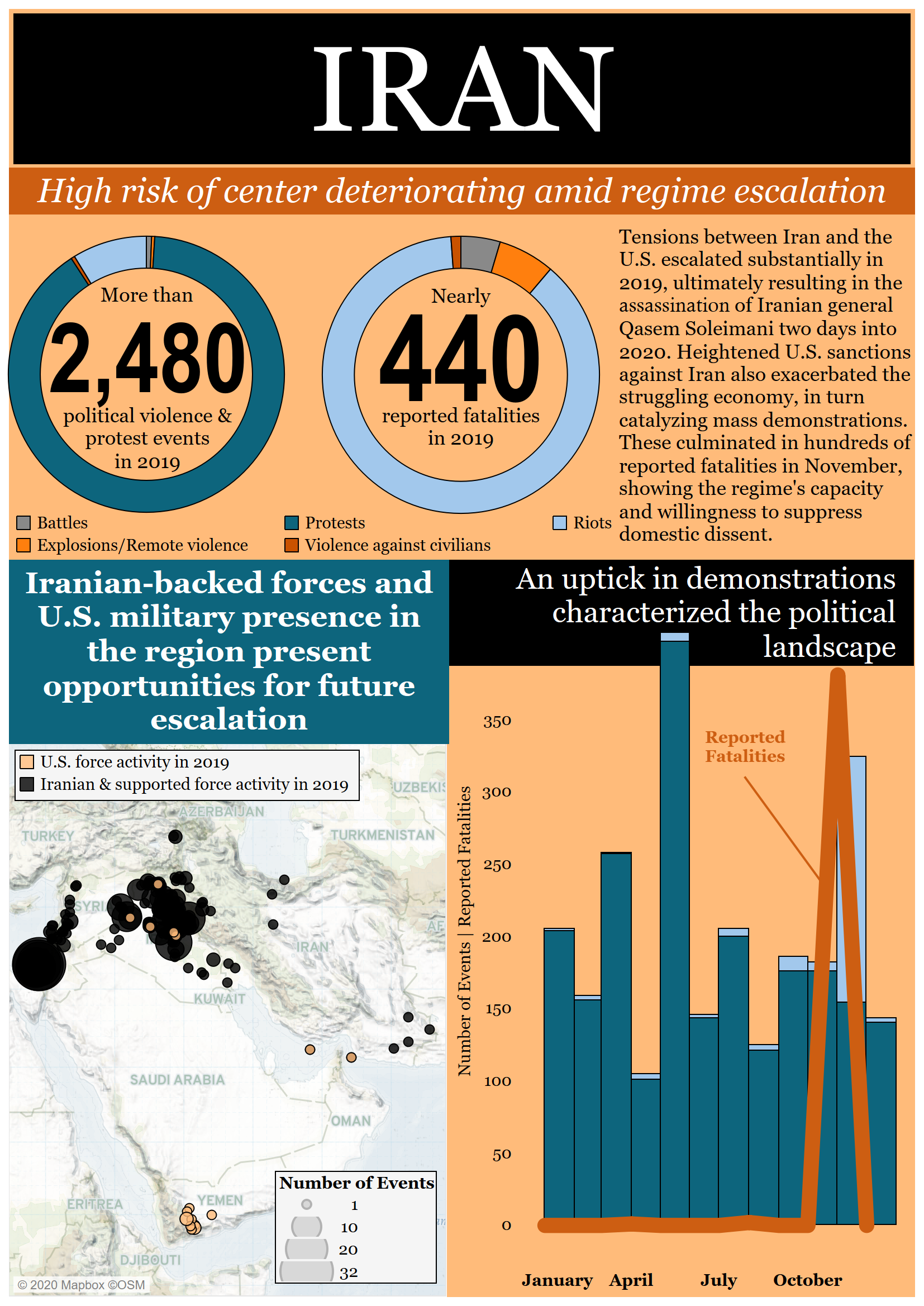

High risk of center deteriorating amid regime escalation at home and abroad

Tensions between Iran and the US have steadily intensified since 2018, evolving into armed confrontation after the Commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Quds Force, Qasem Soleimani, was killed by a US drone strike in Iraq on 2 January 2020. Iran retaliated by launching more than a dozen missiles at two Iraqi bases housing US forces in Anbar and Erbil. Hours later, the IRGC accidentally shot down a Ukraine International Airlines plane and killed all 176 people on board, most of them Iranian citizens. For three days, Iranian officials denied responsibility for the incident, before they admitted that the plane – which reportedly flew close to a military site near Tehran – was mistaken for an American cruise missile (Business Insider, 10 January 2020).

Tensions first began to escalate in May 2018, when President Donald Trump announced the US withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), reinstating all sanctions that had been lifted as part of the nuclear accord. Since then, the Trump administration has imposed additional sanctions on Iran and designated the IRGC as a foreign terrorist organization. The officially stated aim of Trump’s “maximum pressure” policy is to force Iran to negotiate a new deal that would entail accepting tougher restrictions on its nuclear activity and missile program as well as ending its support of militant groups in the Middle East (Al Jazeera, 21 May 2018).

However, instead of accepting more concessions, Iran has adopted a policy of “maximum resistance” (Crisis Group, 5 November 2019). Since July 2019, Iran has gradually rolled back its commitments under the nuclear deal, announcing after Soleimani’s death that it will no longer observe any of the JCPOA limitations (BBC, 5 January 2020). Furthermore, Iran shot down a US surveillance drone and seized a British-owned oil tanker near the Strait of Hormuz last summer. A series of other incidents, including attacks on several oil tankers and two major Saudi oil facilities, have also been blamed on Iran.

Yet undoubtedly, US sanctions have inflicted significant harm on Iran’s economy, which has long suffered from mismanagement and corruption. This has led to increased discontent among the Iranian public with the ruling elite, which manifested itself in mass demonstrations that erupted in more than 100 cities and towns across Iran following a sharp hike in fuel prices last November. In many places, demonstrations turned into riots, with hundreds of banks, petrol stations, and government sites burned down or vandalized (Reuters, 26 November 2019). In one of the most violent crackdowns since the 1979 Revolution, Iranian security forces killed hundreds of demonstrators in less than a week, while arresting thousands more. ACLED records over 380 reported fatalities, though the true toll is likely to be higher (ACLED defers to a conservative fatality estimate based on available reports; for more on ACLED fatality methodology, see this primer). The recent unrest showed the significant capacity and willingness of the regime to repress domestic opposition. As most demonstrations were held in provincial towns and working class areas, it suggested there may be an absence of a broad social base willing to push for radical change (Transatlantic Puzzle, 24 December 2019).

What to watch for in 2020:

There are a number of questions remaining about how the military conflict between the US and Iran will unfold. The two countries are now engaged in their most serious confrontation in recent decades, though in the meantime both sides have signalled restraint (Los Angeles Times, 8 January 2020).

Iran has been “cautious, defensive, and prudent in resorting to force” since the end of the Iran-Iraq War (Carnegie Endowment, 1 April 2014). It knows that its conventional forces are no match for the superior US military. The relatively minor missile attacks on US bases in Iraq, which according to US and Iraqi officials caused no casualties, indicate that Iran does not intend to provoke an all-out war (Washington Post, 9 January 2020). However, Iran could aim to disrupt shipping in the Strait of Hormuz or launch cyber attacks. Moreover, Iran maintains a network of proxies around the region that could be mobilized to target US interests and assets, as well as those of US allies. At a press conference following the missile strikes on the Iraqi bases, the Commander of the IRGC aerospace division stood in front of the flags of six Iranian-backed armed groups: Lebanese Hezbollah, the Iraqi Popular Mobilization Units, Palestinian Hamas, Yemeni Ansar Allah, and the Fatemiyoun and Zainebiyoun brigades, both active in Syria. He implied that future acts of retaliation against the US would be carried out by these so-called ‘resistance groups’ (Independent, 12 January 2020). An attack by an Iranian-backed armed group that results in American deaths – regardless of how directly it is orchestrated by Tehran – could spur Trump to respond militarily against Iran. The situation could then spiral into full-scale war.

The recent US-Iran conflict also has the potential to impact Iran’s domestic stability. Soleimani’s death briefly unified disparate sectors of Iranian society in nationalist sentiment. But the government’s belated admission that it downed the passenger jet has once more stirred up anti-government protests in several cities across the country. It remains to be seen if security concerns will supersede the general frustration and discontent with the political system. Voter turnout in the parliamentary elections next month may provide an indicator of true public support for the Iranian regime.

Additionally, the nuclear standoff will be a major development to watch in 2020. Britain, France, and Germany have triggered a dispute resolution mechanism that could lead to the reinstatement of UN sanctions. However, European diplomats have stressed that the recent step has not been taken to reimpose sanctions on Iran, but to increase the urgency of talks in hopes of bringing Iran back to full compliance. Iranian officials, for their part, have voiced readiness to reiterate “any good will and constructive effort” (Guardian, 14 January 2020). Iran’s latest nuclear deal announcement was vague, indicating that the country’s nuclear program would now be guided by “technical needs.” The Iranian government can therefore decide to either maintain the status quo or to quickly increase enrichment activities based on future circumstances, including the ability of the Europeans to deliver on sanctions relief (Atlantic Council, 7 January 2020). But if negotiations remain fruitless and sanctions are snapped back, Iran has warned that it would withdraw from the nuclear nonproliferation treaty (Guardian, 15 January 2020). The prospects for a tougher deal that would impose more far-reaching limitations on Iran than those agreed under the JCPOA remain slim. Iranian ruling elites consider their ties to regional armed groups, as well as Iran’s missile program, as essential parts of the country’s defense strategy. It is highly unlikely that more external pressure will push them to succumb to such constraints.

Further reading:

- War Drums: Rising Tensions Between the US and Iran

- Call Unanswered: A Year of Protest in Iran

- Borderline: Foreign Support and Spillover Conflicts in Iran’s Volatile Border Zones

High risk of rising violence targeting civilians

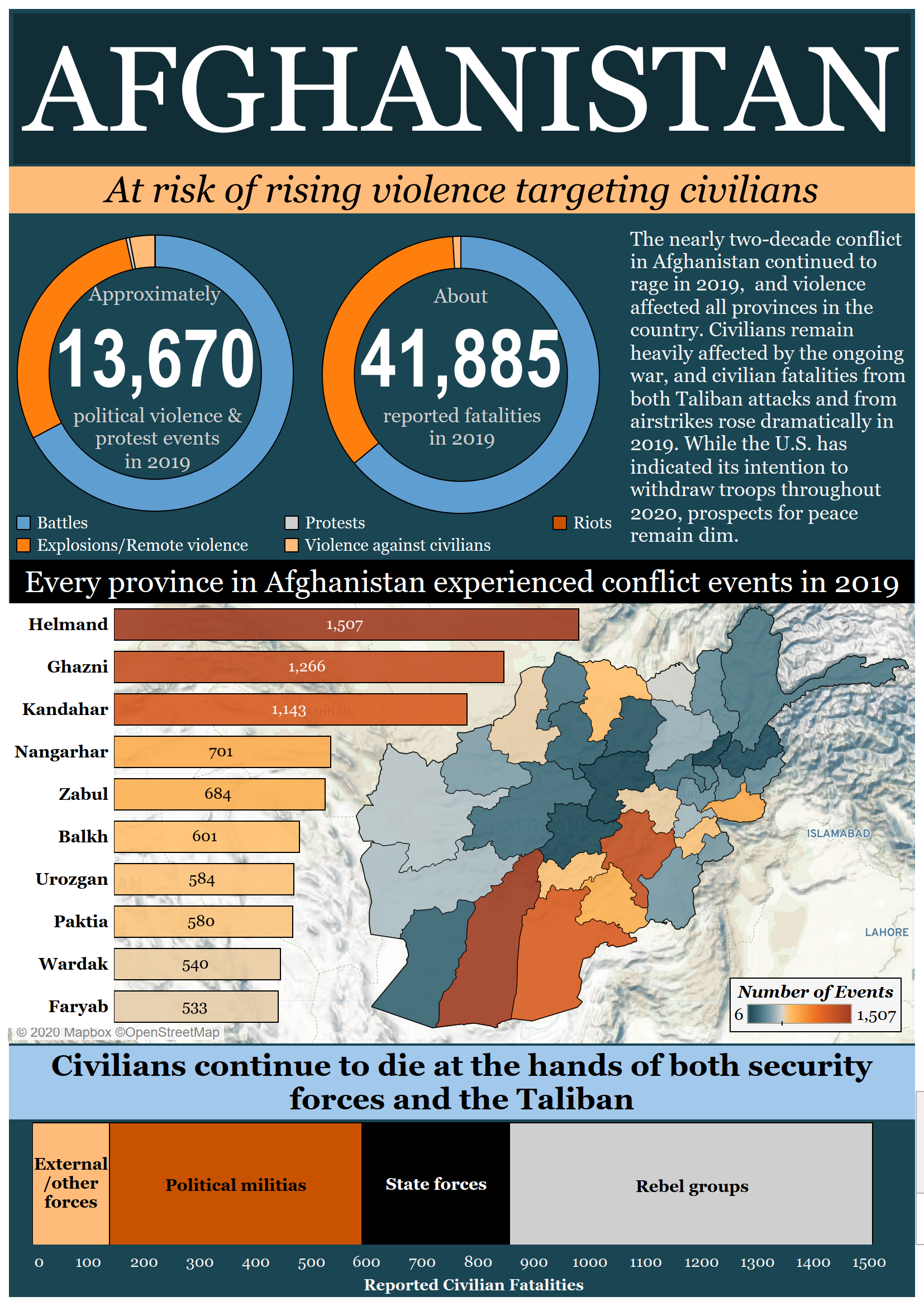

The year 2019 began and ended with hopes for a peace agreement between the US and the Taliban to end the 18-year war that started with the American invasion of Afghanistan in 2001. Political violence continued apace across the country, however. Similar to recent years, violent events were reported in all 34 provinces throughout 2019. The Taliban remained resilient and by far the most active insurgent group, engaging in more than 10,000 reported conflict events with pro-government forces. ACLED records the highest number of violent events involving the Taliban in the provinces of Helmand, Ghazni, and Kandahar, which also accounted for more than 25% of the total number of reported fatalities in 2019.

The Islamic State of Khorasan (IS-K) also remained active in Afghanistan in 2019, launching dozens of attacks on government and civilian targets. However, after years of military offensives by American, Afghan, and Taliban forces, IS-K collapsed in the eastern province of Nangarhar – the group’s main stronghold – following the surrender of several hundred fighters and their families to the Afghan government in November (VOA, 21 November 2019). The group’s activity declined last year compared to 2018, although it remained responsible for some of the deadliest attacks targeting civilians, including a bombing at a wedding ceremony in Kabul that reportedly killed more than 90 Shiite Afghans (BBC, 16 September 2019). But the overall number of civilians killed through direct or indiscriminate IS-K attacks (non-battle events) decreased by more than 60% compared to the year prior.

Nevertheless, the conflict in Afghanistan continued to have a devastating impact on civilian lives. As negotiations between the Taliban and the US continued, warring parties strived to gain leverage at the table by showing strength on the battlefield. There was an uptick in violence particularly in the third quarter of 2019, as the two sides got close to an agreement before US President Donald Trump abruptly suspended the talks in September (BBC, 8 September 2019). On the one hand, US and Afghan forces ramped up their ground and aerial operations: the number of aerial strikes conducted in 2019 rose by approximately 20% compared to 2018, leading to one third more reported civilian fatalities. On the other hand, Taliban militants launched large offensives on a number of provincial capitals and against security forces to gain ground or consolidate their position. The number of reported civilian fatalities from direct or indiscriminate Taliban attacks (non-battle events) increased by more than 30%.

The upsurge in Taliban violence can be partially attributed to the group’s operations targeting voters, election workers, and campaigners around the September presidential election. After issuing warnings exhorting citizens to refrain from participating, Taliban forces launched several attacks on election rally sites and polling centers aimed at disrupting voting, resulting in dozens of reported fatalities (NPR, 28 September 2019). Voter turnout was low: with approximately a million initial votes purged due to irregularities, only 1.8 million ballots were counted, representing less than 20% of registered voters and 12% of the total voting age population (Afghanistan Analysts, 22 December 2019). On 22 December, Afghanistan’s Independent Election Commission announced the preliminary results after a two-month delay amidst allegations of fraud. President Ashraf Ghani received over 50% of the vote, crossing the threshold necessary to avoid a run-off with a thin margin of fewer than 12,000 votes. Given Ghani’s narrow victory, the election might go to a second round as Afghanistan’s Electoral Complaints Commission continues to review thousands of complaints lodged by Chief Executive Abdullah Abdullah and other presidential candidates (VOA, 26 December 2019).

What to watch for in 2020:

The new decade started for Afghanistan with the Trump administration pushing ahead with plans to partially withdraw US troops “with or without” a peace deal with the Taliban (Al Jazeera, 17 December 2019). It is anticipated that the number of troops will be reduced from about 13,000 to 8,600 in the near future, most likely by the November 2020 US general election (NBC, 2 August 2019). If a US-Taliban deal is reached, a further phased withdrawal of US and NATO forces in exchange for security guarantees by the Taliban is to be expected. The likelihood of a successful outcome of the negotiations – which were resumed after Trump paid a surprise Thanksgiving visit to US troops in Afghanistan – is high. There is a mutual desire to end the long war, which US officials have acknowledged to be “largely stalemated” (CRS, 5 December 2019).

However, the prospects for intra-Afghan peace are much more uncertain. The Taliban has so far refused to engage in formal direct negotiations with the Afghan government, which it claims is illegitimate. A US-Taliban accord is expected to pave the way for intra-Afghan talks to establish power-sharing arrangements and a permanent ceasefire. But before any substantial reduction in violence can be achieved, the two sides will have to agree about the future of Afghanistan’s democracy and electoral process, rights of women, the fate of heavily armed warlords, and a host of other highly contentious issues (USA Today, 29 December 2019). The unsettled state of Afghan politics and the continued political disarray in Kabul will likely further complicate any future negotiations. If peace talks fail, intensification of fighting could pose a serious threat to the Afghan government unless the US is willing to extend its military mission in the country.

Also unknown is the future of IS-K in Afghanistan. While its collapse in Nangarhar was a major setback, the group’s fighters remain active in Kunar and several other provinces. There are concerns that a peace deal could drive Taliban forces to IS-K, enabling the group to expand its insurgency. IS-K could especially appeal to mid- and low-level Taliban commanders who may lose out in a peace deal, or the militants who wish to continue the fight against those who they see as infidels. Furthermore, the group could be a refuge for Taliban fighters who fear retribution if they were to return home after years of hostilities (Reuters, 15 August 2019). The Afghan government will need to provide robust reintegration programs in order to reduce this risk.

Further reading:

- Map | The Taliban: 2018 & 2019

- The World According to the Taliban: New Data on Afghanistan

- War of Attrition: A New Year of Violence in Afghanistan

- Eastern Afghanistan: A Tale of Two Provinces

- Fighting Bullets with Ballots: Afghanistan’s Chaotic Election

- ACLED Methodology and Coding Decisions around the Conflict in Afghanistan

At risk of increased fragmentation despite a popular leader

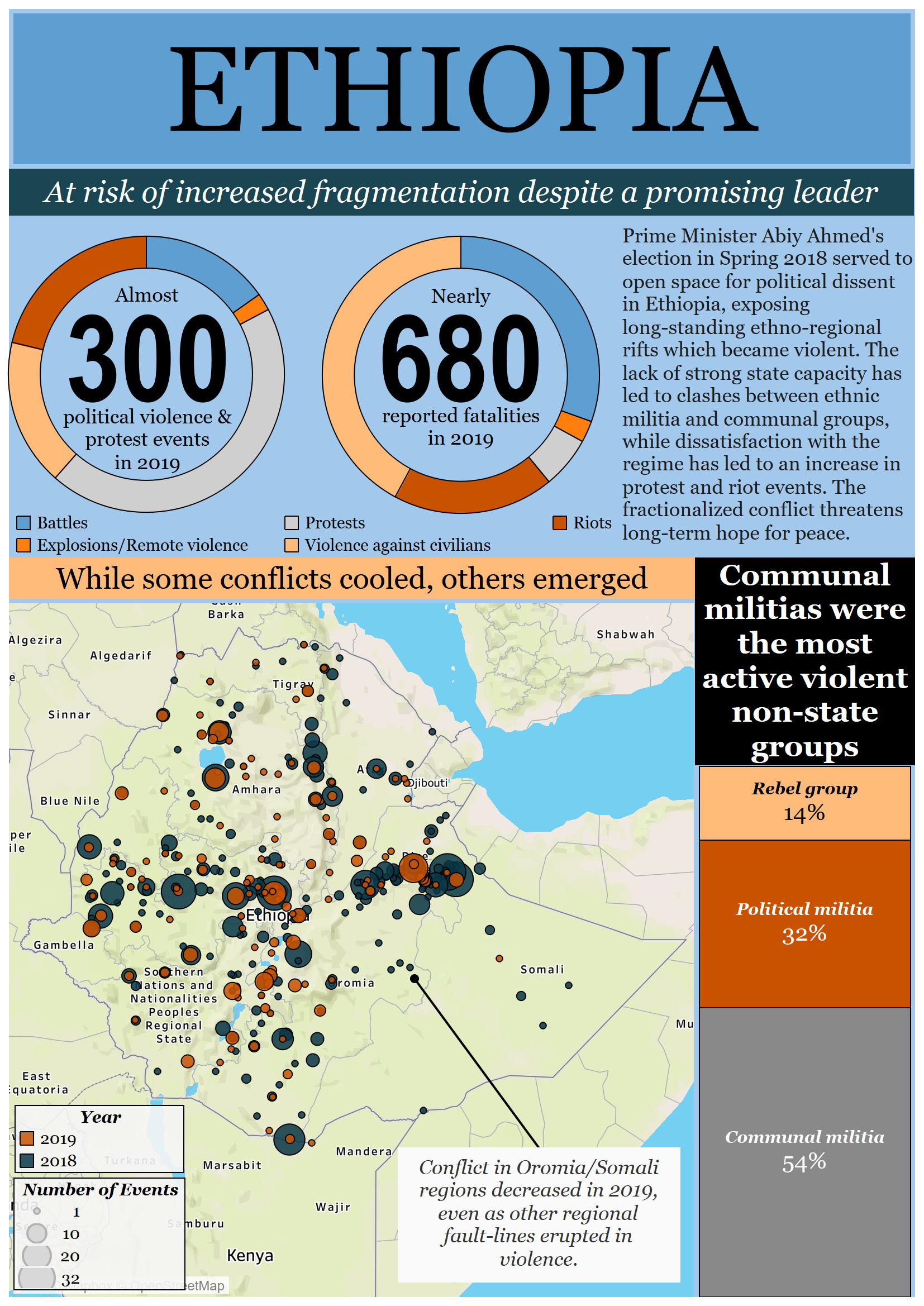

From fatal fights on university campuses to serious armed conflict, political violence in Ethiopia has shifted from resistance against the regime to ethnic strife, including riots and clashes instigated by ethnic militias. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s failure to adequately control the situation could jeopardize the Nobel Prize winner’s performance in the upcoming election, as many in Ethiopia have been pulled into societal fractures amid weak state control and the general deterioration of security nationwide.

Since coming to power in May 1991, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), led by the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), maintained a tight lid on competition between ethnically based federal states through harsh repression of media and political opposition movements. After his election in the spring of 2018, Prime Minister Abiy has opened political space significantly, allowing for a number of opposition groups to return to the country from abroad and participate in political activism (BBC, 29 June 2019).

The creation of political space and the return of armed resistance groups and activists with ethno-regional interests has exposed a weak central security apparatus in Ethiopia, demonstrated by the immediate rise and geographical spread of conflict between ethnic groups. While major clashes on the Oromia-Somali regional state borders cooled significantly during 2019, new conflicts have arisen across the country. During the second year of Abiy’s term, ACLED has recorded clashes between ethnic militias and communal groups near the Oromo-Afar regional state borders, the Guji Oromo-Gedeo community border areas, the Amhara-Gumuz regional state borders, the Oromo-Benishangul Gumuz regional state borders, and the Oromo special zones in Amhara region, among others – resulting in the displacement of millions (Africa News, 13 May 2019). ACLED records hundreds of fatalities resulting from ethnic conflict over the past year.

People living outside of their own ethnic zones, including a number of university students, have also faced increasing attacks. In October 2019, Oromia Media Network (OMN) owner Jawar Mohammed accused the government of attempting to assassinate him after his security guards were removed during the middle of the night. Protests by his supporters, mostly Oromo youth “Qerroo,” turned violent and resulted in at least 67 fatalities. Many of the dead were reported to have been ethnic minorities living in Oromia (AP, 26 October 2019). More recently, mosques and Muslim-owned businesses have been targeted for arson in East Gondar (Addis Standard, 21 December 2019), Amhara Christians have been attacked in the Bale-Robe area of Oromia, and several university students were killed by unidentified perpetrators or fellow students (Reuters, 10 December 2019).

Guerilla-style violence has also taken place within regional zones throughout the year, as those supporting the central government come into conflict with ethno-nationalist groups. Splinter factions of the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) led by Jaal Marroo are accused of launching several attacks on regional officials and police forces in western Oromia (BBC Amharic, 2 December 2019). Similar violence has occurred in the Amhara region, including the successful assassination of Amhara regional leaders and the chief of staff of Ethiopia’s military.

ACLED records frequent protest events throughout the year, many in support or opposition to the Prime Minister’s reformist agendas. Others, often more violent, forwarded demands for enhanced cultural and political autonomy for ethnic groups in the country. These were especially amplified after the merging of the former ruling coalition, the EPRDF, into a single “Prosperity Party,” which dissolved five regional parties into a single block ahead of next year’s elections. While this was Abiy’s attempt at appealing toward a more unified national identity outside of his support base in Addis Ababa, opposition “federalists” largely supported by Ethiopia’s large rural populations feel that the merger forms the “structural foundation for a unitary state that will rob them off their [cultural] dignity and autonomy” (Al Jazeera, 5 December 2019).

Amidst the political uncertainty, and fearing a loss of cultural identity among a new centralization of power, at least two ethnic groups currently administered under Ethiopia’s Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People’s region are making bids for statehood. Weeks of protests rallies held in Hawassa culminated in a successful referendum that determined Sidama as Ethiopia’s 10th semi-autonomous regional state. (Addis Standard, 23 November 2019). Leaders of the Wolayta ethnic group are making a similar bid. Potentially more serious are a number of political movements that are vehemently opposed to Abiy’s ethno-nationalistic aims, including those advocating for complete succession (Ethiopian Insight, 28 September 2019).

What to watch for in 2020:

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has thus far maintained a delicate balance between advancing the interests of his own ethnic group, the Oromo, and pushing for a more united Ethiopia. His reformist agendas have been met with much applause from the international community. Yet, many in his own country view the changes with skepticism, as ethnic conflict has engulfed parts of Ethiopia. Large factions of the Oromo community that were key to ousting the old government accuse the Prime Minister of forgetting the many lives that were lost during the protest movements that ultimately put him in power (BBC, 23 October 2019).

2020 will be a pivotal year in Ethiopia. Central to political debate will be the future autonomy of Ethiopia’s ethno-regional states and the role of the capital, Addis Ababa, which has an ethnically diverse population despite its location in the heart of the Oromia region. Violence associated with border regions and competition over resources could worsen significantly if federal forces are unable to contain the situation. Federalist agendas and the push for greater autonomy in Ethiopia’s regional states are already shaping the country’s political landscape ahead of the 2020 election (Africa News, 2 January 2020), amplifying tensions between ethnic groups. Lastly, Egypt’s opposition to Ethiopia’s building of a hydropower dam on the Nile has threatened conflict for many years. While outright war is not likely, Egypt and other stakeholders could attempt to influence Ethiopia’s domestic politics by working with various ethnic groups in an attempt to sway future plans concerning the dam (BBC, 7 November 2019).

Ethiopia’s struggles with ethnic federalism are not over. Fractures in Ethiopian society are deep, with some differences dating back to the Amhara-controlled imperial regimes. If proper precautions are not taken, ethnic conflict and the fragility of the Ethiopian political system could lead to disaster in the 2020 election year.

Further reading:

- Ethiopia Sourcing Profile

- Bad Blood: Violence in Ethiopia Reveals the Strain of Ethno-Federalism under Prime Minister Abiy

- Change and Continuity in Protests and Political Violence in PM Abiy’s Ethiopia

High risk of protests devolving into organized violence

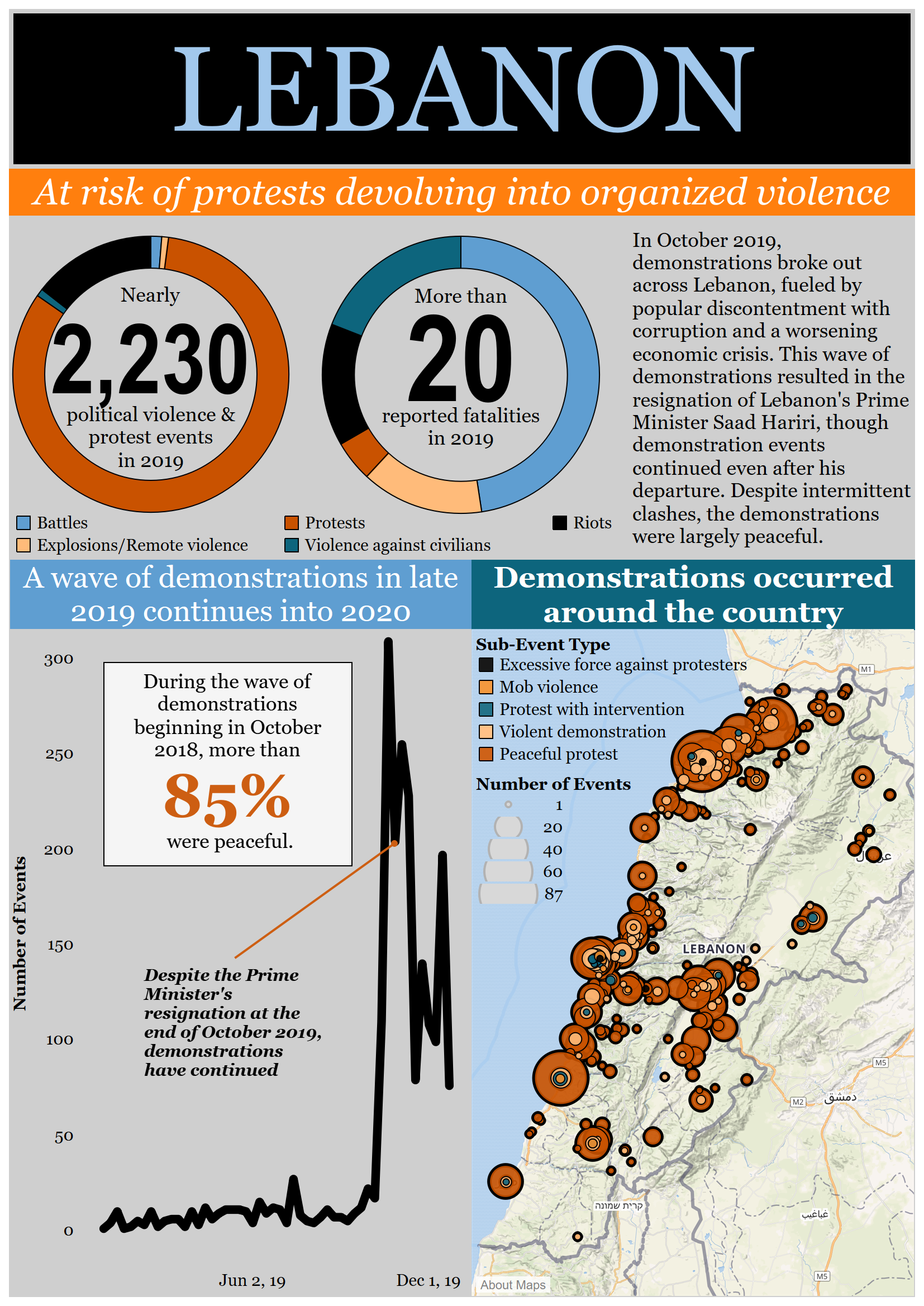

Government mismanagement and a worsening economic crisis has resulted in a popular protest movement against Lebanon’s political system and ruling elite. Since mid-October 2019, Lebanese citizens across all sectors and demographics have taken to the street to express a variety of grievances with the government. The demonstrations initially began in the capital of Beirut after the cabinet announced a proposal to increase taxes on messaging apps, including WhatsApp, as well as tobacco and petrol as part of a series austerity measures (BBC, 7 November 2019). Under pressure, the government withdrew the tax proposal and by the end of October, Prime Minister Saad Hariri announced his resignation (BBC, 29 October 2019). A new government appointed in late January has coincided with protests developing into more violent riots.

Clearly, neither Hariri’s departure nor a new regime is enough to end the protest movement. Lebanese citizens remain deeply frustrated with the political class, whose negligence has led to economic crisis and poor distribution of services. The political system in Lebanon was designed to balance the power of different religious sects against one another following the 1975-1990 civil war. However, this system is increasingly viewed as obsolete and fostering political incompetence and corruption. The government has consistently failed to provide basic public services, such as electricity, water, waste management, and health care. At the same time, citizens are suffering from the rising cost of living, stagnation in wages, and increasing unemployment rates.

ACLED records the highest concentration of demonstrations in Lebanon’s major cities of Beirut, Sidon, and Tripoli. The number of demonstration events is also notably high in the northern Akkar governorate, where protests are typically less common than in other regions.

What to watch for in 2020:

Despite intermittent clashes, the protest movement remained remarkably peaceful until late January. There are indications that violence will escalate, as unrest may intensify the longer this situation continues in the absence of major government reforms. Protesters are demanding an end to corruption, the replacement of the government with independent experts, and an end to the sectarian political system. Students have been taking an increasingly prominent role in the demonstrations. Rationing of electricity and water, as well as restrictions on bank withdrawals have led to increased frustrations among the public. The former Minister of Economy said that Lebanon needs a financial bailout of between $20 and $25 billion. If conditions continue to get worse in Lebanon, this will fuel anger among the general public and the demonstrators.

Former education minister and university professor, Hassan Diab, was nominated to replace Prime Minister Hariri by Shia parties Hezbollah and Amal in addition to the Maronite Future Patriotic Movement (FPM). Hassan Diab considers himself a technocrat and has promised to form a government of independent experts by the end of January. However, he was unable to gain the support of the Sunni-led bloc which may present obstacles to securing Western aid (BBC, 19 December 2019). This move appears to have done little to quell the protests. Just 10 days after Diab’s nomination, protesters called for his resignation outside his house (Guardian, 28 December 2019). In the beginning of 2020, Diab’s public reception as well as his ability to actually sustain a government of independent experts will be put to the test. Additionally, with tensions running high between US- and Iran- allied groups, it remains to be seen how this will play out in Lebanon between various political parties – particularly with Iran’s prominent ally Hezbollah.

Developed, democratic political system at risk of turning violent

Violent political instability is on the rise in the US. A study conducted by the Associated Press, USA Today, and Northeastern University found that the “US suffered more mass killings in 2019 than any year on record,” with 41 attacks resulting in 211 fatalities (BBC, 29 December 2019). According to the latest statistics from the FBI, violent hate crimes hit a 16-year high in 2018 (Al Jazeera, 13 November 2019), while that same year a database tracking violence perpetrated by law enforcement agencies reported that “police brutality in America is getting worse” (The Appeal, 17 April 2018).

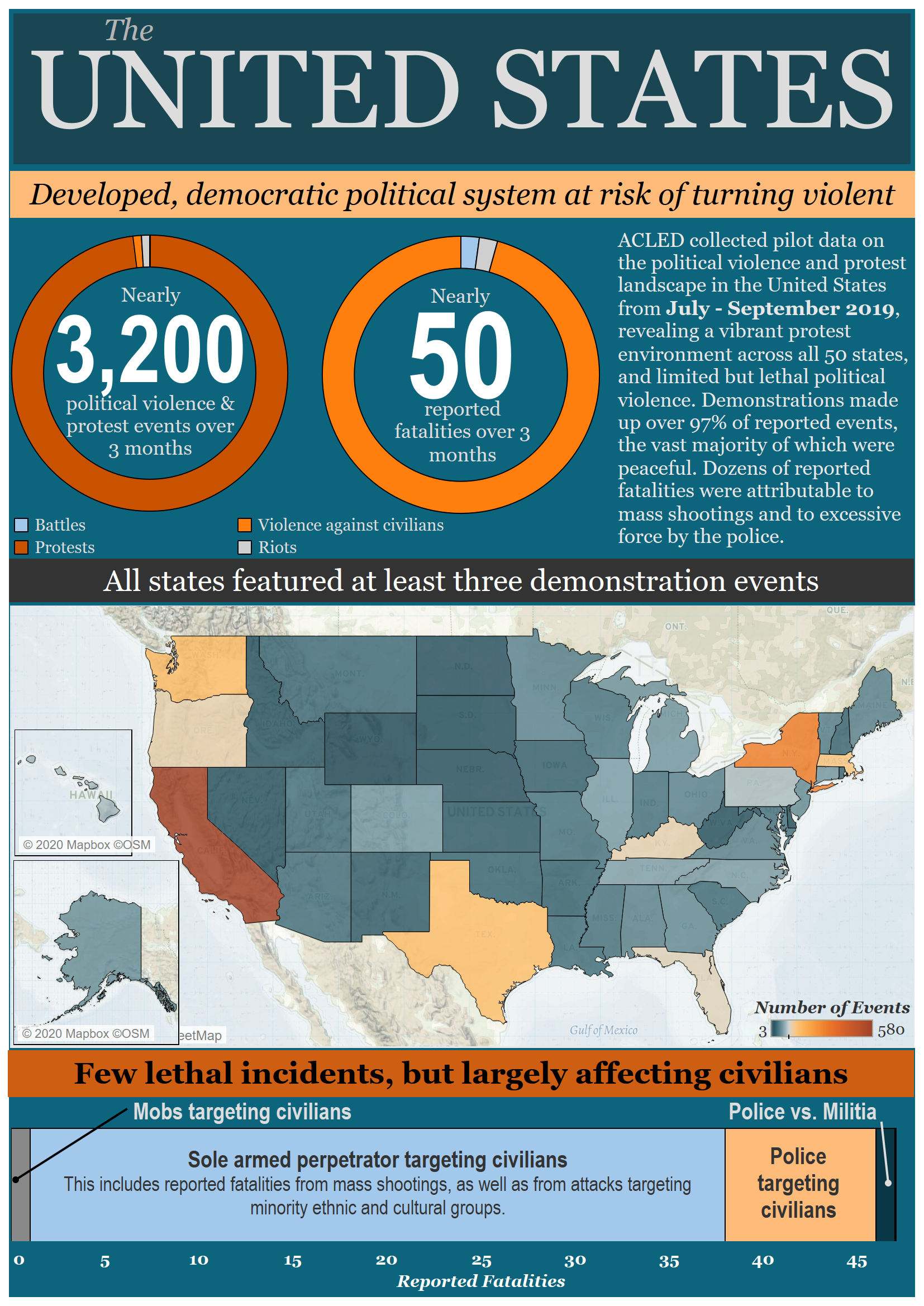

In the summer of 2019, ACLED launched a pilot project to systematically track all forms of political violence and demonstration activity across the US in real-time. Over three months from July through September, ACLED collected data on approximately 3,200 events; while the vast majority of these events are peaceful protests, the project also recorded political violence events ranging from mass shootings and hate crimes to non-state militia activity and police brutality.

The findings from this pilot project speak specifically to trends in political violence — not all forms of violence — but they provide a snapshot of two key trends in American disorder.

First, political violence is limited, but lethal. While violent events make up only 1% of the pilot data, they resulted in nearly 50 fatalities — a disproportionately deadly trend linked primarily to mass shootings. ACLED also records 16 events involving excessive force by police, more than half of which target racial and ethnic minorities. Likewise, more than 20 hate crimes against minority groups are recorded during this period, including seven attacks targeting members of the LGBTQ+ community, particularly transgender women.

Second, the US is home to a robust protest environment. ACLED records over 3,100 demonstration events across all 50 states, ranging from a minimum of three events in Wyoming to a maximum of almost 600 in California. During the three-month pilot period, more demonstration events were recorded in the US than in almost any other country in the ACLED dataset — second only to India, a country with more than four times the population of the US. Though peaceful protests account for the overwhelming majority of these events, ACLED data show that nearly 5% of non-violent demonstrations were met with intervention or excessive force, with this figure rising to more than 9% for protests involving Native Americans, nearly 10% for those involving minority religions, and more than 11% for those involving supporters of the Democratic Party.

What to watch for in 2020:

The trends identified in ACLED’s pilot data are likely to intensify around the 2020 general election. There are significant latent risks across the US that are continuously exacerbated by hyper-partisan rhetoric and divides. So much so that, in October 2019, a poll conducted by Georgetown University indicated that a majority of Americans believe the country is “two-thirds of the way” to outright civil war (New York Magazine, 25 October 2019). The vote to impeach Republican President Donald Trump in the Democrat-controlled House of Representatives this past December deepened party divides. In response to the inquiry, the President has ratcheted up his vitriolic rhetoric, which may further fuel political violence (NPR, 5 October 2019; Reuters, 18 December 2019). Before the vote, President Trump tweeted a quote suggesting that impeachment would cause a “Civil War like fracture in this Nation from which our Country will never heal” [sic] (The New Yorker, 5 October 2019), and he has increasingly indicated that any attempt to remove him from office — either in Congress or at the ballot box — will be considered illegitimate (Politico, 21 June 2019). Although the President is well-known for hyperbolic statements, there is evidence that far-right “armed militias are taking Trump’s Civil War tweets seriously” (Lawfare, 2 October 2019). As early as August 2019, a Guardian study documented 52 incidents in which supporters of the President “carried out or threatened acts of violence” since the start of his 2015 campaign (Guardian, 28 August 2019).

At the same time, there are growing concerns that a volatile foreign policy threatens to generate disruptive ‘boomerang’ effects at home. The President’s January 2020 decision to assassinate Iranian military commander Qasem Soleimani has immediately increased the risk of attacks on US service people and citizens. More broadly, there is continuing concern that foreign-born citizens will experience additional negative repercussions of travel bans and related policies, particularly those of Iranian, Middle Eastern, and Latin American origin (New York Times, 5 January 2020; Buzzfeed News, 10 January 2020). With minority groups in the US at increased risk of violence and intimidation, state-sanctioned targeting on the basis of nationality raises red flags.

The President’s announcement that he is considering the designation of select Mexican drug cartels as ‘terrorist organizations’ has also raised the specter of American military action on the border (NPR, 27 November 2019). Though the Mexican government has repeatedly rejected US military intervention, further militarization and internationalization of the anti-drug fight could intensify violence in border areas and exacerbate the ongoing migrant crisis. Under the US government’s new Migrant Protection Protocols program, also known as the “Remain in Mexico” policy, approximately 54,000 migrants have been sent to northern Mexico to await legal processing, where they face regular attacks by criminal gangs (Wall Street Journal, 28 December 2019). Further strain on the immigration system could in turn translate to increased domestic tensions in the US, amplifying the risks faced by vulnerable migrant and Latinx communities. In August 2019, a white nationalist opened fire inside a Walmart shopping center in El Paso, Texas, killing 22 civilians including eight Mexican nationals. The suspect reportedly justified the shooting — which was the deadliest attack recorded during ACLED’s three-month pilot — as “a response to the Hispanic invasion of Texas” (Guardian, 10 October 2019).

Simultaneously, the largest protest movement recorded during ACLED’s pilot project was the “Lights for Liberty” campaign, which called for immigration reforms like ending the “Remain in Mexico” policy and the closure of migrant detention centers. Though these demonstrations — which accounted for 44% of ACLED’s pilot data and involved hundreds of events — were largely peaceful, there are risks of violent confrontations, especially with President Trump said to be making immigration the “centerpiece” of his reelection campaign (The Hill, 11 April 2019). The only instance of excessive force used against peaceful protesters during ACLED’s pilot period was an event in August in Rhode Island, where a corrections officer drove his truck into protesters surrounding an ICE facility as part of a nationwide action (Washington Post, 16 August 2019) — pointing to how demonstrators organizing on this issue could be met with violence.

More broadly, there are heightened risks of clashes between protesters and counter-protesters going into an increasingly polarized 2020 election environment. There were multiple cases during the pilot period where clashes between demonstrators became violent. For example, following a Trump rally in Cincinnati in August, a scuffle broke out between protesters and Trump supporters, resulting in punches being thrown and an arrest needing to be made (CBS News, 2 August 2019). In Beverly Hills in September, pro-Trump supporters and anti-Trump demonstrators clashed, again with punches being thrown and police needing to engage (CBS News, 18 September 2019). These confrontations could escalate as the election approaches. With fewer than 300 days until the vote, the US faces a real threat of serious political disorder.

Further reading:

ACLED is currently seeking support to continue data collection for the United States. If you wish to assist the project, please contact us at [email protected].

© 2020 Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). All rights reserved.