Situation Summary: 25-31 May

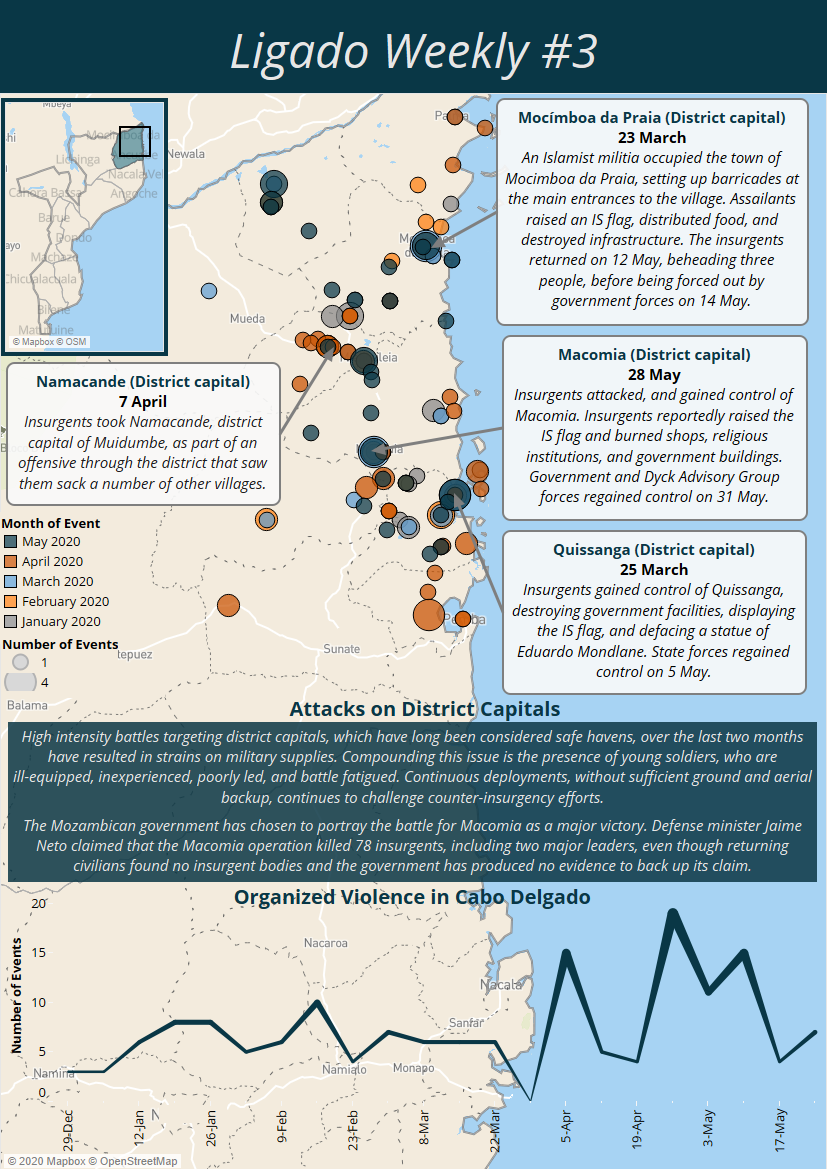

The insurgency in Cabo Delgado came roaring back to life last week after a short lull, with insurgents forcing government forces from the district capital of Macomia on 28 May. That attack, which killed at least 17 civilians and five members of the Mozambican police Rapid Intervention Unit and potentially many more, marks the fourth district capital insurgents have taken in the last three months. Government forces are back in control in Macomia, but the attack has sparked another mass exodus of civilians in search of safety from the conflict. The government has portrayed the battle as a victory and claimed to have killed two insurgent leaders, but government spokesmen have offered no proof for the claim and their victory narratives ring hollow. The fundamental dynamics of the conflict remain unchanged — insurgents continue to demonstrate the ability to strike at will within the established conflict zone, government forces remain stretched and unable to provide effective security within the province, and civilian confidence in the government’s ability to protect them continues to drop.

Incident Focus: Battle for Macomia

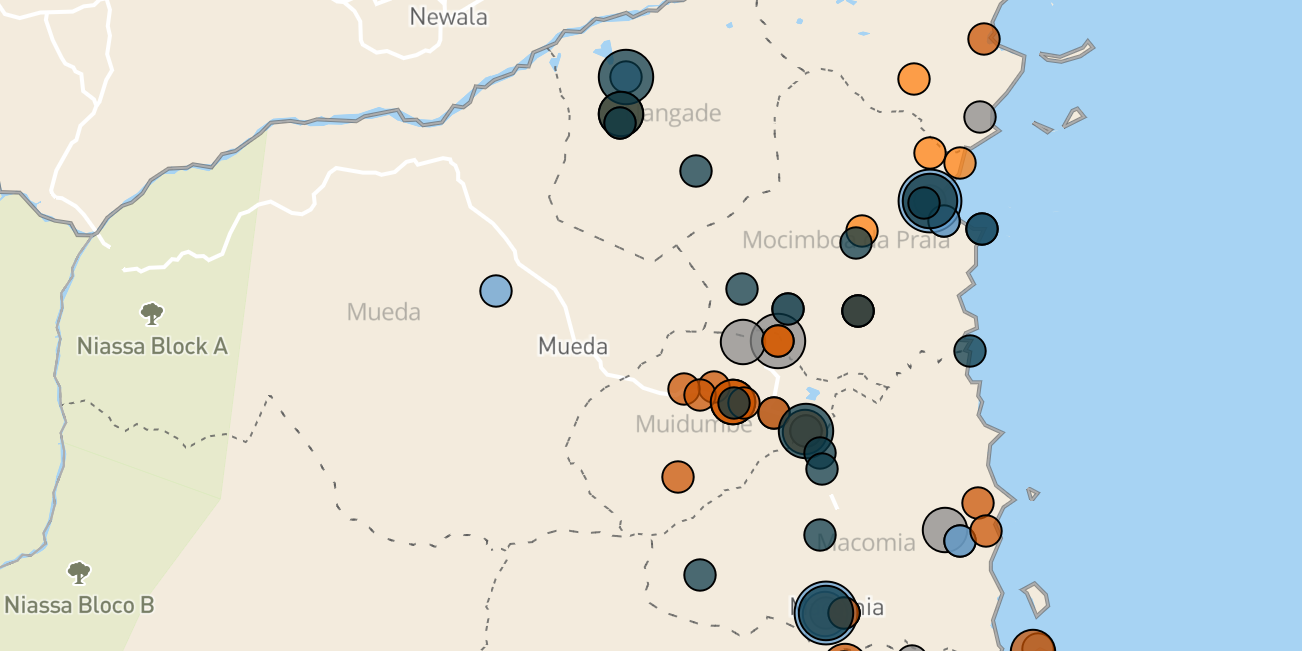

In the early morning of 28 May, an estimated 90 to 120 insurgents attacked Macomia town, along with the villages of Chai and Litamanda, both in Macomia district (Zitamar News, 1 June 2020). The attackers, dressed in Mozambican security force uniforms and armed with rocket-propelled grenades and a Chinese-built armored personnel carrier equipped with a W85 heavy machine gun captured from government forces in Mocimboa da Praia district on 12 May, attacked Macomia from three directions, cutting off the major roads exiting the town. After a brief but intense battle with Mozambican forces stationed in the town, government troops fled and insurgents had the run of the district capital. The attack, on a garrisoned government force commanded by a brigadier general, was the best organized and executed the insurgents have yet perpetrated.

During their time in control of Macomia town, insurgents reportedly prayed at a local mosque, hoisted the ISIS flag in the town center, and looted food and medical supplies. They then burned down certain homes, government buildings, shops, and other sites associated with state governance and religious authority. Notable targets include the local Movitel and Vodacom mobile phone stalls, the central market, the Macomia jail, town hall, health center, primary and technical schools, and police station, the local World Food Programme office, the agricultural extension office, and the mosque of sheikh Sujai Aifa. The burning of the mosque is particularly notable since as recently as last September the government had named Aifa as a financier for the insurgency (Carta de Mocambique, 26 September 2019). To cap it off, insurgents also destroyed a power facility on the outskirts of town, plunging surrounding areas into darkness on the night of 28 May.

Government forces soon regrouped, and reinforcements arrived by vehicle from unaffected areas of Macomia district as well as Quissanga and Meluco districts. Private military contractors Dyck Advisory Group (DAG) also ran helicopter gunship missions from Pemba. Insurgents changed from military uniforms to civilian clothes when the helicopters arrived in an effort to confuse the gunners. The helicopters fired anyway, and, in coordination with government ground troops, returned the town to government control by 31 May.

The government claimed to have killed 78 insurgents in their counterattack, including two insurgent leaders, although no proof of those claims has been forthcoming (see further analysis in Government Response). In addition to whatever insurgents were hit, six children in the town were also injured by fire from the helicopter gunships. The children eventually made their way to the provincial hospital in Pemba. Other locals reported helicopters firing indiscriminately on civilians trying to flee the town during the battle. The injured children are the first civilian casualties to be directly linked to private military company involvement in Cabo Delgado, though they will likely not be the last.

When civilians reentered Macomia town to pick up the pieces, they found 17 bodies of their fellow townspeople in the area, although locals believe that more bodies will be found in the coming days. Four were children who died of hunger while hiding from the fighting in the bush, and roughly as many were beheaded by insurgents. It is not clear how many of the remaining civilian fatalities were caused by insurgents and how many by the government or their DAG allies. Some reports have claimed that helicopters have dropped bombs, both on insurgents and civilians, but DAG helicopters do not seem to be equipped with rocket pods.

The deaths by hunger underline how fragile the humanitarian situation is in Macomia, as well as much of the rest of the conflict zone. Macomia held a number of internally displaced people before the attack, as its contingent of government troops seemed to render it safe. Since the attack, many have fled, including a caravan of about 250 refugees that arrived in Pemba on 1 June, which will further stretch limited resources for displaced people in southern Cabo Delgado.

As security advisor Johann Smith noted in his analysis of the attack, the Macomia battle strained the government’s new combined arms approach to the conflict (Zitamar News, 1 June 2020). Macomia is just under 100km by air from the DAG helicopter base at Pemba airport, and with the DAG helicopters’ limited range and lack of safe forward operating base the gunships were forced to return to Pemba to refuel frequently. The limited time-over-target was further hampered, Smith wrote, by problems paying for fuel in Pemba.

From the outset of their involvement in the conflict, DAG raised concerns about conducting air support operations with only three helicopters and without effective ground support. The thick overgrowth of northern Cabo Delgado hampers the precise detection of insurgents, and overland supply lines are long and fragile. The Macomia attack accentuated these shortcomings, as well as exposing the problems with using helicopter gunships among concentrations of civilians. The need for ground support, however, may provide a role that other Southern African Development Community countries can fulfill, either through direct support or through supply and training, if they respond to Mozambique’s reported calls to enter the conflict.

Government Response

The Mozambican government has chosen to portray the battle for Macomia as a major victory, despite the fact that the last time they claimed the tide had turned in the conflict — Interior Minister Amade Miquidade’s address to parliament on 27 May — insurgents sacked Macomia the next day (Sala da Paz, 27 May 2020). Defense minister Jaime Neto claimed that the Macomia operation killed 78 insurgents (despite the fact that returning civilians found no insurgent bodies and the government has produced no evidence to back up their claim), among them two major rebel leaders, both Tanzanian. Nuno Rogeiro, a commentator on the conflict who has tended to talk up the government’s response, claimed that the two allegedly dead leaders went by the names Ndrorogue and Ambasse. Rogeiro offered no evidence for the claim (Noticias ao Minuto, 31 May 2020).

Indeed, the government’s history of intelligence about insurgent leadership is weak at best. Mozambican police held the Ugandan cleric Abdul Rahman Faisal for a year as the insurgency strengthened before trotting him out as a major rebel leader. As noted above, police tried to arrest Sujai Aifa in Macomia last year on suspicion of being an insurgent financier, but their mission failed because he was in Pemba, and now insurgents have torched his mosque. All government claims to have neutralized insurgent leadership should be greeted with major skepticism in the absence of supporting evidence.

In his address to parliament, Miquidade also claimed that insurgents are using drones, which has not been substantiated but is certainly possible. If true, small drones could give insurgents a useful reconnaissance capacity, particularly since civilians would have a hard time differentiating between insurgent drones and drones the government has used since its collaboration with Wagner Group mercenaries. It could also add to the low morale and overall feeling of dread reported by Mozambican soldiers deployed to Cabo Delgado. As one soldier stated to a contact in Mocimboa da Praia, “once I have taken leave I am never coming back”.

Note: There is often a lack of consensus over the spellings of place names in Mozambique. We endeavor to be consistent within Cabo Ligado publications, but be aware that alternative spellings exist and may appear in other publications.

© 2020 Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). All rights reserved.