By the Numbers: Cabo Delgado, October 2017-June 20201Figures updated as of 20 June 2020.

- Total number of organized violence events: 465

- Total number of reported fatalities from organized violence: 1,288

- Total number of reported fatalities from civilian targeting: 838

All ACLED data are available for download via the data export tool, and a curated Mozambique dataset is available on the Cabo Ligado home page.

Situation Summary

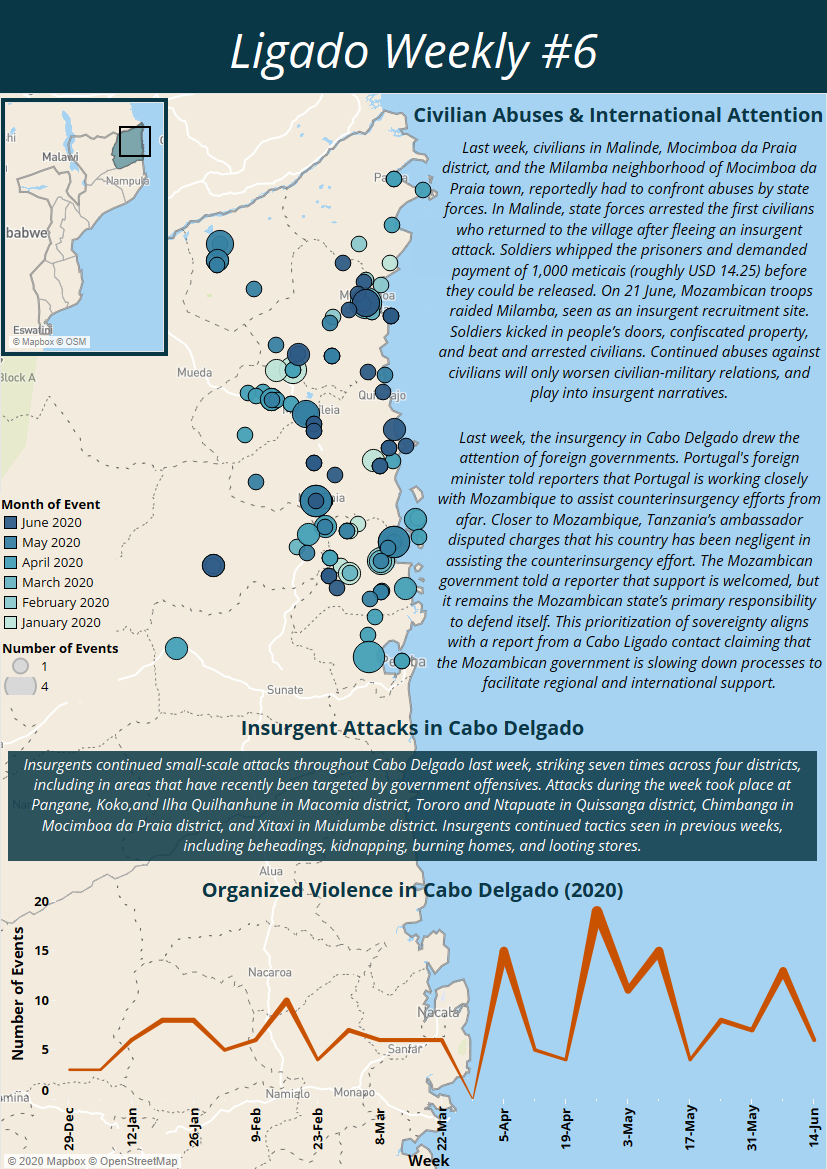

Insurgents continued their spree of small-scale attacks throughout the conflict zone last week, striking seven times across four districts, including in areas that have recently been targeted by government offensives.

Last week’s first insurgent attack came at Pangane, on the Macomia district coast, when fighters killed two civilians and kidnapped a child and an adult on 15 June.

On 17 June, insurgents carried out attacks in three different districts. In Tororo, Quissanga district, they beheaded four civilians who had refused to follow insurgent orders to leave the Bilibiza area. The attackers also kidnapped a woman. In Chimbanga, on the N380 in Mocimboa da Praia district, insurgents killed three civilians in a morning attack, then kidnapped a man and released him after beating him. In Koko, Macomia district, insurgents burned homes and killed a man who they found inebriated in the village.

Two days later, insurgents returned to the area near Bilibiza, beheading a civilian in Ntapuate, Quissanga district. Also on 19 June, insurgents looted shops and burned homes in Xitaxi, Muidumbe district, the site of a massacre by insurgents in April that, according to government claims, ended with at least 52 civilians dead.

In addition, there was an undated report of insurgents burning a boat carrying fresh water to and from Ilha Quilhanhune in Macomia district, and six new corpses were recovered in Ingoane, Macomia district, following an insurgent attack there on 9 June.

Finally, a Dyck Advisory Group (DAG) Bat Hawk ultralight crashed near Miangalewa, Muidumbe district, on 15 June. A DAG representative told International Crisis Group (ICG) consultant Piers Pigou that the crash took place during a non-combat surveillance flight and that the pilot survived and was evacuated to a South African hospital, an account that was confirmed by another source.

In all, insurgents killed at least 11 civilians last week. The attacks themselves utilized the same tactics as last week’s incidents — small cells that are hard for government forces to track making quick attacks, never remaining in one place too long. Those tactics appearing in areas like western Quissanga district and Xitaxi, where the government has claimed victories in recent months, highlights both the insurgents’ strategy of forcing the government to spread its resources to respond to attacks and the government’s inability to provide durable security in areas it claims to have liberated from insurgent control.

Incident Focus: Government Malfeasance at Malinde and Milamba

While many civilians manage the unease that comes from the lack of government security force presence near their homes in the conflict zone, some are dealing with a more immediate problem: what to do when Defense and Security Forces (FDS) come to their homes demanding money. Residents of the Malinde, Mocimboa da Praia district, and the Milamba neighborhood of Mocimboa da Praia town, were forced to confront that problem repeatedly last week, resulting in a major breakdown in relations between soldiers and civilians.

Malinde was the target of an attack on 14 June in which the assailants claimed to be FDS soldiers before killing three civilians. The attackers seem to have been insurgents — an FDS response actually broke up the attack — but some Malinde citizens believed the perpetrators to be government troops (Carta de Mocambique, 16 June 2020). That distrust only increased when the FDS arrested the first civilians who returned to the village after fleeing the attack. Soldiers whipped the prisoners and demanded 1,000 meticais ($14.25) — five times the official cost of a bus ticket to the relative safety of Mueda — to let them go. As other civilians returned to the village, they found that soldiers had looted their belongings in their absence, storing things at the local barracks and claiming to have been protecting them from fire.

Just south of Malinde, in the Milamba area of Mocimboa da Praia, a similar fracturing of the civilian-military relationship played out. Police were seen extorting money from civilians there on 18 June, and the situation soon boiled over. Milamba is seen as an insurgent recruitment site, and recently two young people from the area joined the insurgency willingly and another 10 girls were reported kidnapped. In response, a company of Mozambican troops raided the neighborhood on 21 June, kicking in people’s doors, confiscating cell phones and other property, ransacking houses, and beating and arresting civilians. The FDS claimed to be searching for insurgents hiding among the populace, but there is no indication that they found any.

These actions, disturbing in their own right, play directly into narratives the insurgency has pushed in these exact areas. As insurgents have withdrawn northward through Mocimboa da Praia district in the face of a government offensive, numerous reports have emerged of them counseling civilians to flee before government troops arrive, lest they be mistreated by FDS soldiers. The civilians now facing the brunt of FDS corruption and overbearing tactics disregarded the insurgents’ warnings, choosing to allow themselves to be returned to state control. That does not augur well for the government convincing other civilians to make that same decision in the future.

Government Response

To the Mozambican government’s credit, it did take action last week to reduce FDS troops’ incentive to loot. On 16 June, Mozambican president Filipe Nysui announced that soldiers deployed to Cabo Delgado will receive a bonus, augmenting their pay. Assuming the money actually reaches the enlisted ranks — a major assumption, given the military’s ongoing troubles with paying its soldiers on time and in full — it will at least prevent soldiers from having to prey on the civilian population for food and other necessities (Radio Mocambique, 16 June 2020).

The government also claimed a military success last week, with police operations director Victor Novela displaying photos of machetes, motorbikes, and other items recovered from insurgents during operations in Muidumbe district (Twitter, 18 June 2020). The recovered items are an achievement for the government insofar as they demonstrate that FDS attacks forced insurgents to leave valuable resources behind, but they also raise an uncomfortable question. The government and sympathetic members of the media have made a range of claims in recent weeks about battles won, insurgents killed, and materiel recovered that far exceed the items Novela displayed, but no photographic evidence of those claims has been forthcoming. Why show a collection of machetes but not provide evidence to back up the assertion, for instance, that government forces killed two insurgent leaders in Macomia district?

If the military was to provide such evidence, it might appear on the new website, defesamoz.info, offering news on the conflict from a pro-Mozambican government perspective, which was unveiled last week. The site is slick, and portrays the military as an effective counterinsurgency force, but the Defence Ministry has denied any connection to the project. Instead, it appears to be a semi-official propaganda effort. ICG’s Pigou commented that the site’s commitment to a strict security lens “suggests that human security priorities [in Cabo Delgado] will, for the moment at least, remain relegated” to the background of government messaging. It is not immediately clear who the public relations move is directed towards, but the message being broadcast is that the war in Cabo Delgado can be won with the hard power at the military’s disposal.

On the international assistance front, the prospect of military support for Mozambique in Cabo Delgado has become a political issue in Portugal. Portuguese foreign minister Augusto Santos Silva told reporters that Portugal is already working closely with Mozambique to assist counterinsurgency efforts from afar (Platforma, 16 June 2020). The opposition PSD, however, called for Portugal to deploy troops to Cabo Delgado as part of a mission organized by the UN or another multilateral body.

Closer to home, Tanzania’s ambassador to Mozambique, Rajabu Luhwavi, disputed charges that his country has been negligent in assisting Mozambique’s counterinsurgency effort (VOA, 19 June 2020). Tanzania’s silence on the issue, especially as it heads SADC, has been puzzling. Describing cooperation between the two countries, Luhwavi said, “we are trying to work together with the [Mozambican] government, and along the border we carry out joint operations with the participation of different defense and security forces.” The Mozambican government told a reporter that support is welcomed, but it remains the Mozambican state’s primary responsibility to defend itself. This prioritization of sovereignty aligns with a report from a contact claiming that the Mozambican government is slowing down processes to facilitate regional and international support in the fight against insurgents.

Finally, a report emerged last week in Africa Monitor of growing tension between Mozambican police (and specifically the paramilitary Unidade de Intervencao Rapida), who have been the lead agency in the government’s counterinsurgency effort and have done some of the sharpest fighting of the conflict, and the Mozambican military, which is dissatisfied at being cut out of the potentially lucrative contracts associated with the conflict (Africa Monitor, 12 June 2020). Specifically, DAG’s contract is with the police, rather than the military, which rankles when there has been so little investment in the military’s own meager helicopter fleet.

The military may complain, but their stature has not grown during the Nyusi administration. As Joseph Hanlon points out, Nyusi named Jaime Neto, who has neither military experience nor great political power, as defence minister this year (The Open University, June 2020). Since the end of Mozambique’s civil war in 1992 necessitated integration of former Renamo fighters into the military, the government’s approach has largely been to limit the military’s role while investing the state’s coercive power in the police, who are more politically reliable. Mozambique is once again integrating Renamo fighters into the state security services, but the Unidade de Intervencao Rapida is not slated to take on any new Renamo officers and is likely to remain Nyusi’s preferred counterinsurgency tool.